![]()

Introduction:

Part 1 (Click Here to Read Part 1) of this three part article, ended at the advent of the era of the Police Department of the City of New York’s (PDNY or NYC PD) use of a voice radio communication. This new method of communication did not replace the many other forms of communication, such as: wireless telegraphy, telephones, teletypewriters, telegraph and others, but rather supplemented them. Communication by voice messages transmitted by radio revolutionized police work, and ultimately the world.

Wireless Telegraphy Slowly Replaced by Voice Radio:

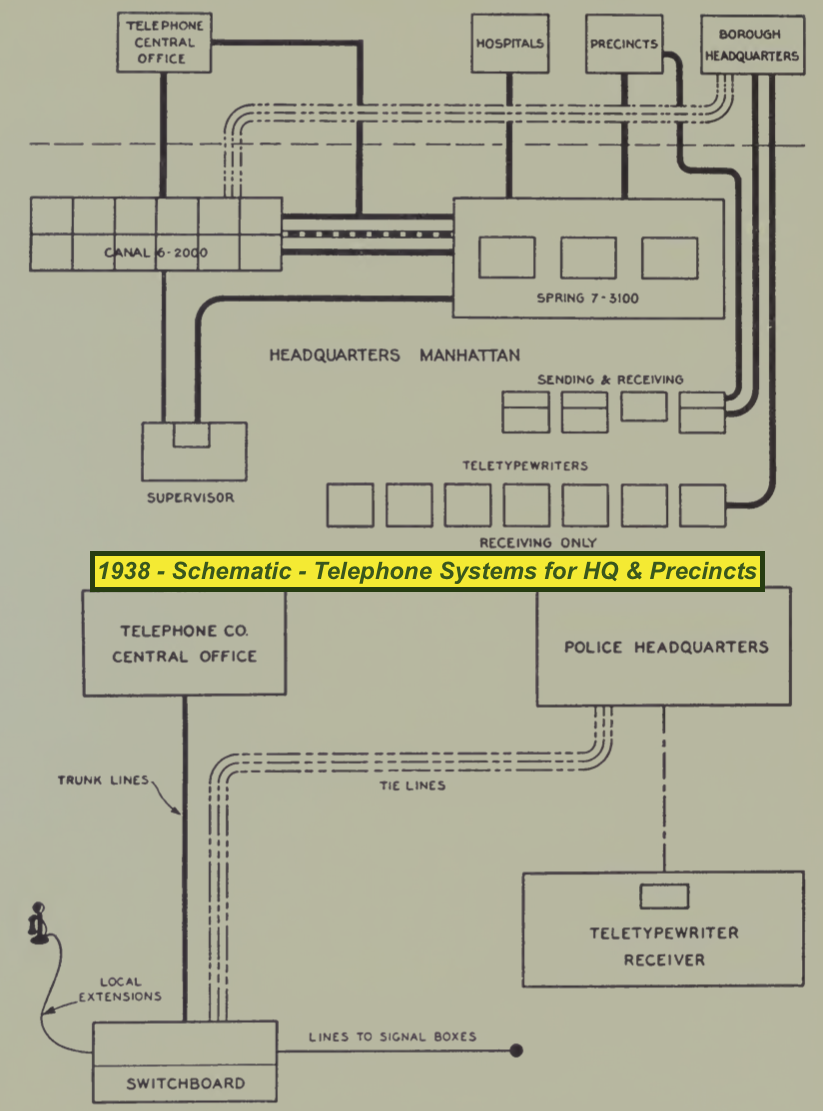

The first broadcast license granted by the federal government to a police department was granted in June 1920 to the NYC PD. The “call sign” designated was “K-U-V-S,” which by 1935 was re-designated “W-P-Y.” At the 1920 Annual Convention of the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), held in Buffalo, NY, a paper was presented by a chief of police on the topic: “Use of Wireless Telegraphy in Police Service.” The premise of the paper was that departments across the country utilize wireless telegraphy to communicate information (data, not voice) with one another. The paper was, however, behind the technology as some departments already installed tele-typewriter lines for inter-departmental communication, a more efficient and accurate means of communication.

The same chief returned to the 1921 IACP convention with an updated paper promoting the installation of wireless voice radio receivers in police automobiles. By this time, departments in eleven cities had radio receiving stations, five had broadcasting stations, and ten had partnered with private entities to use the entity’s station. Again, information presented in the paper was lagging behind the rapidly advancing technology.

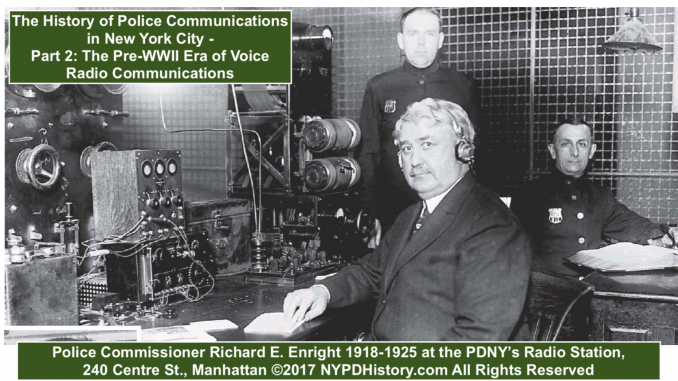

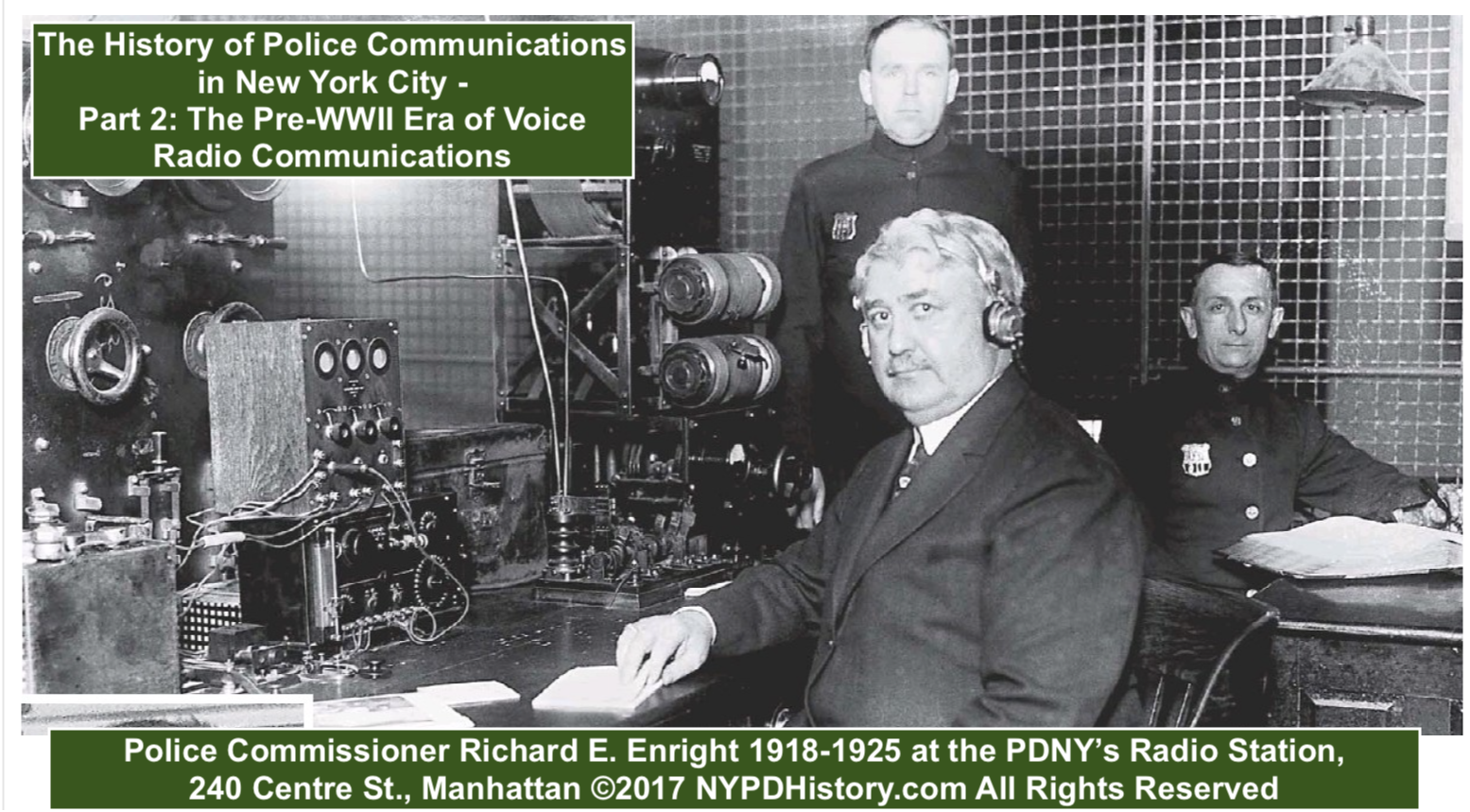

While the NYC PD was the first department granted a radio license, they used it for wireless telegraphy (data) for several years while they experimented with, and tested, voice radio technology. In 1921, Sergeant Charles E. Pearce, who was in charge of the NYC PD’s radio system, used the telegraphy to broadcast information about stolen vehicles, missing persons, and the like. The persons who received the information were not police officers, but civilians who were using amateur radios and ship radios. Transmissions were made from NYC PD Headquarters, located at 240 Centre St., Manhattan, nightly at 7:30 p.m. and 11:30 p.m. By agreement, amateur radio owners/operators (civilians) within range were enlisted to decode the transmissions and turn them over to local police departments.

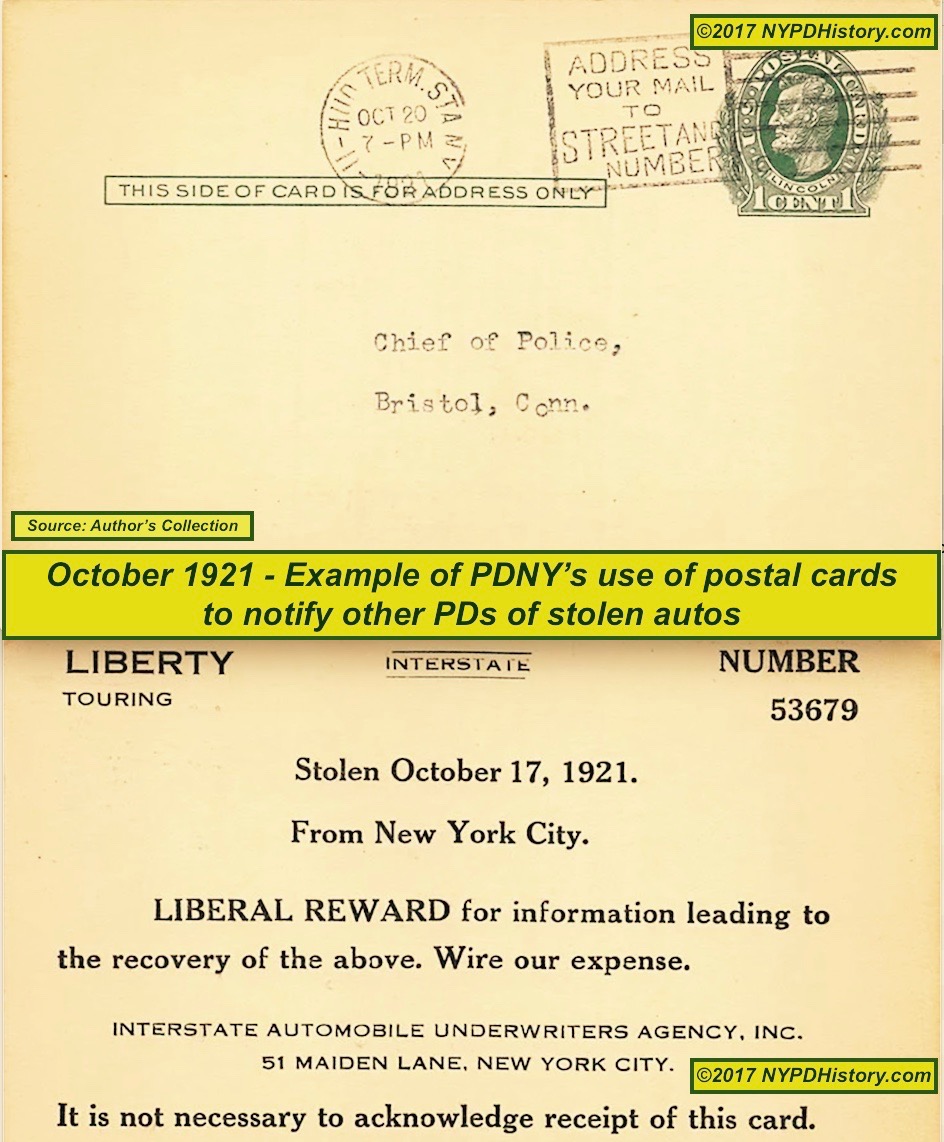

The experiments included enlisting the services of private, non-police radio operators who transmitted police information over the same radio bands used for commercial purposes. Anyone with a home, or commercial, radio receiver was able to listen to the police communications, or switch to another station where a comedy show or music was playing. Additionally, postal cards containing information on stolen autos were mailed to surrounding departments. The obvious disadvantages drove the need for the NYC PD to invest in their own equipment.

The Annual Report for the Police Department of the City of New York for 1922 contains information on the PD’s Telegraph Bureau. The report indicates that the Bureau “comprises five distinct units, one in each Borough Headquarters, maintaining uninterrupted private communication by radio telegraph and telephone, and Morse telegraph equipment.” The Morse equipment was used as an “auxiliary” to the more modern equipment. The Bureau had 113 uniformed and civilian personnel.

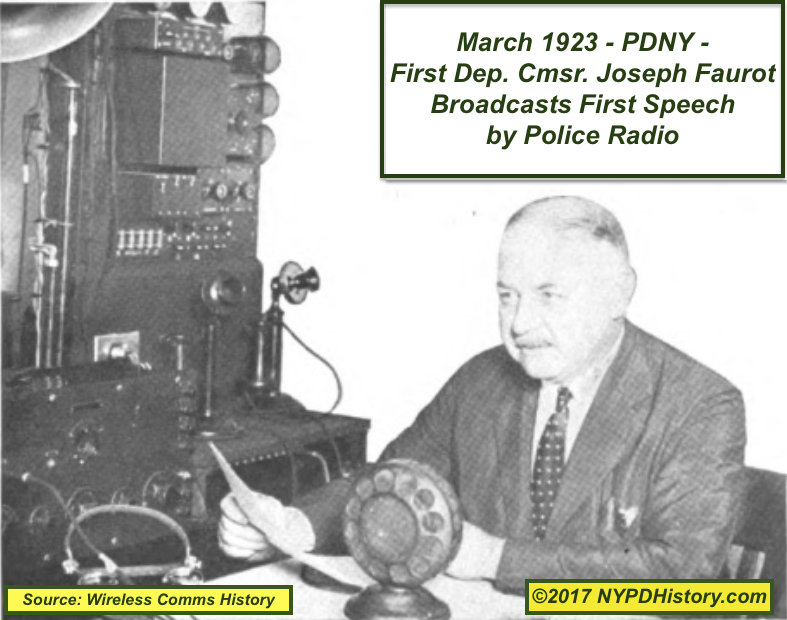

The 1922 report also mentions that Headquarters was “in constant touch, for instance, with the police boats,” particularly mentioning the police boat “John F. Hylan,” (Radio Call Sign K-U-S-M) which patrolled “the waters adjacent to New York” and that there was “in operation, for experimental purposes, the latest approved type radiophone transmitter, No. 1-A Western Electric 500 Watts. The value of the radiotelephone for police purposes has been fully demonstrated.” Prior to the installation of wireless equipment on the police boats, they remained at the docks and awaited dispatches via a wired telephone. The ability to patrol the waterways while awaiting a dispatch was a huge advantage.

One example of the use of wireless involving the police boat John F. Hylan, appeared in a March 1923 magazine dealing with wireless communications. The magazine related an incident that occurred in 1922, where the Captain of a ship, his chief officer, and the wireless operator were barricaded on the bridge of the ship, keeping a mutinous crew at bay. A call went out for help and the police boat met the ship in the harbor and arrested the mutineers.

A statement made by Police Commissioner (PC) Arthur Woods appeared in a 1922 journal on telegraphy/telephony. PC Woods was quoted as having said that the “City’s Police Wireless System was a demonstrated success.”

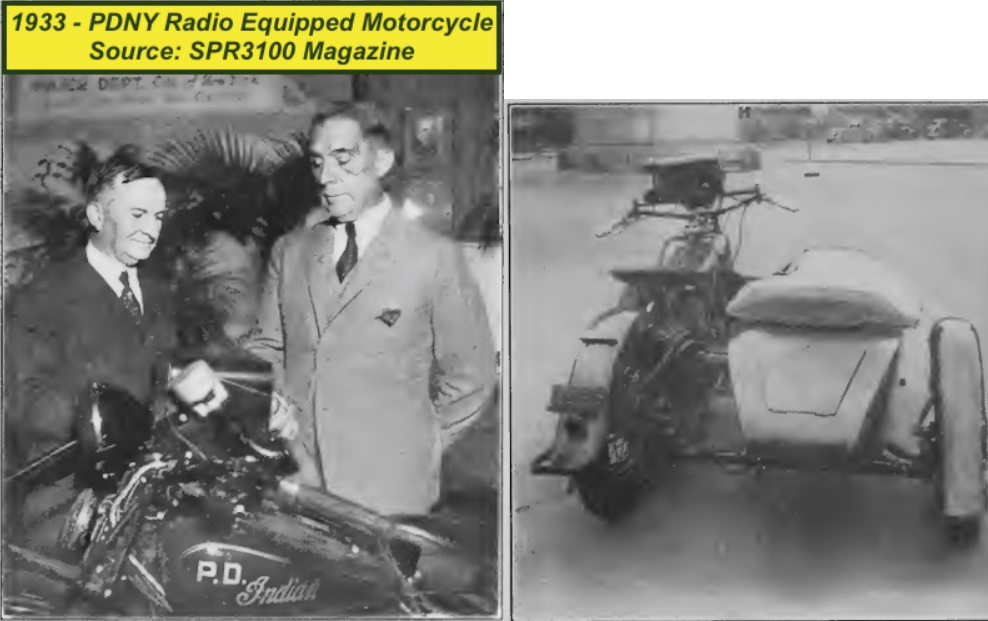

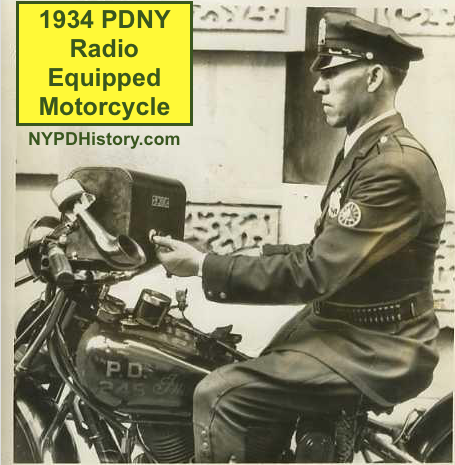

In May 1923, the first radio-equipped PD motorcycle (and in the opinion of Capt. Morris, the first anywhere) was displayed on the occasion of a “Readiness Parade.”

Additional Radio Stations Used by the NYC PD

The NYC PD used another radio station to broadcast messages to citizens via a different frequency using the call letters “W-E-A-F.” Transmissions on this frequency related to public notifications about crimes, wanted persons, major incidents, etc. A third radio system was utilized by the NYC PD, using call letters “K-L-A-W” and included broadcasts of performances by the NYC PD Band and Glee Club and speeches by police officials. The earliest record found in which the ceremony of the presentation of medals earned by NYC PD officers was broadcast live via NYC’s Radio station, call letters “W-N-Y-C,” was that of June 5, 1933.

The driving force in advancing the use of radios in police work, was the increasing use of automobiles by police departments. Motor patrol was replacing foot patrol in many smaller departments which had large areas to patrol. In another 1922 journal on radiotelephony, an article appeared wherein Inspector Michael R. Brennan, Superintendent of Telegraph, NYC PD, was reported to have said that plans were underway to equip all police automobiles with radio receivers, which would operate on a wavelength that would eliminate interference by amateur operators, and that all transmissions would be in code to prevent the possibility of lawbreakers listening to radio calls.

Era of One Way Radio Transmissions From Headquarters to Police Vehicles

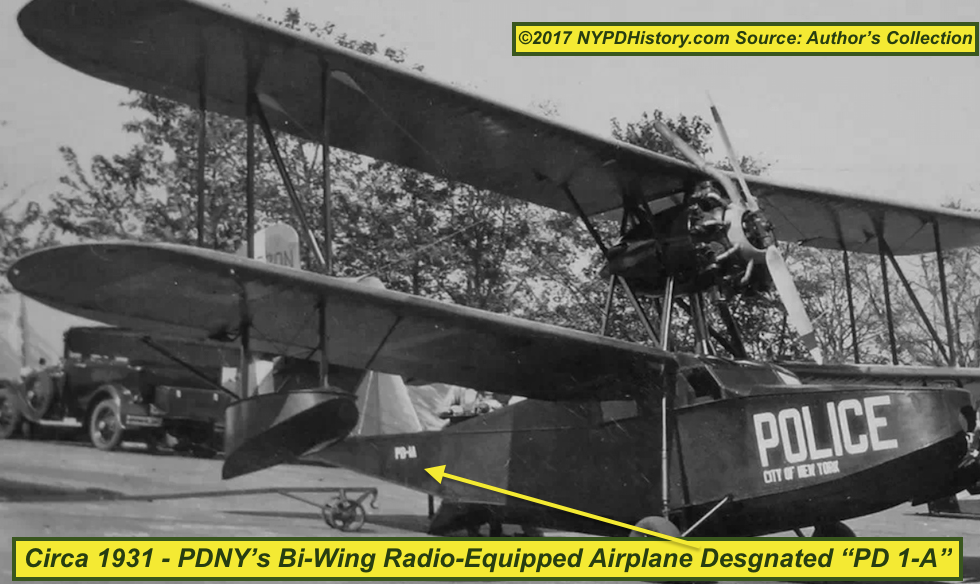

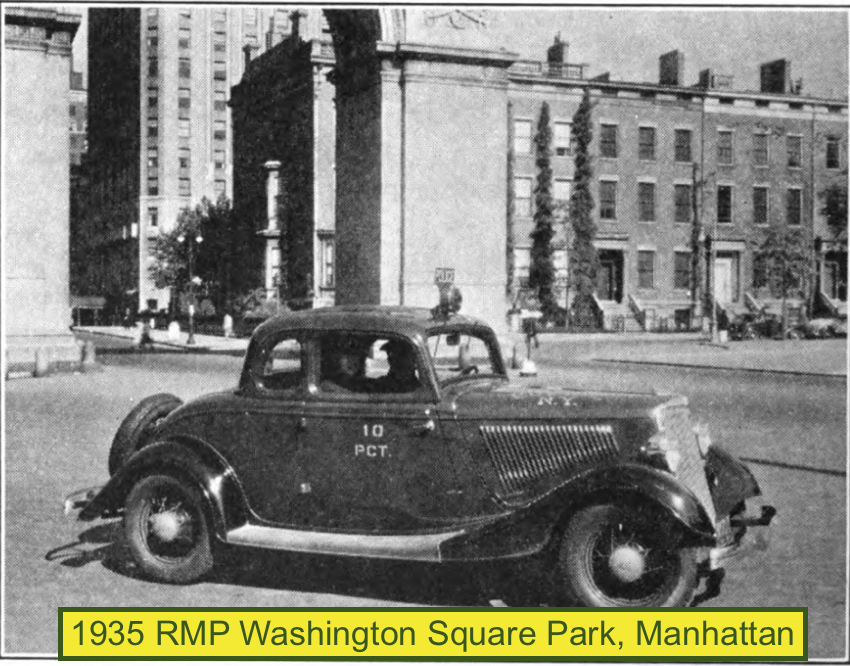

In February 1931, PC Edward P. Mulrooney used a two-way radio telephone to communicate from his desk at Headquarters on Centre St. to a NYC PD airplane, operated by Captain Arthur W. Wallender. This technology, developed for use by civilian aircraft, was limited to this application. According to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper, at the annual parade of the NYC PD, held in May of 1932, radio receiver equipped marked police cars were stationed along the route to receive information from Headquarters. The official name for such cars was, and remains, “Radio Motor Patrols” (RMPs).

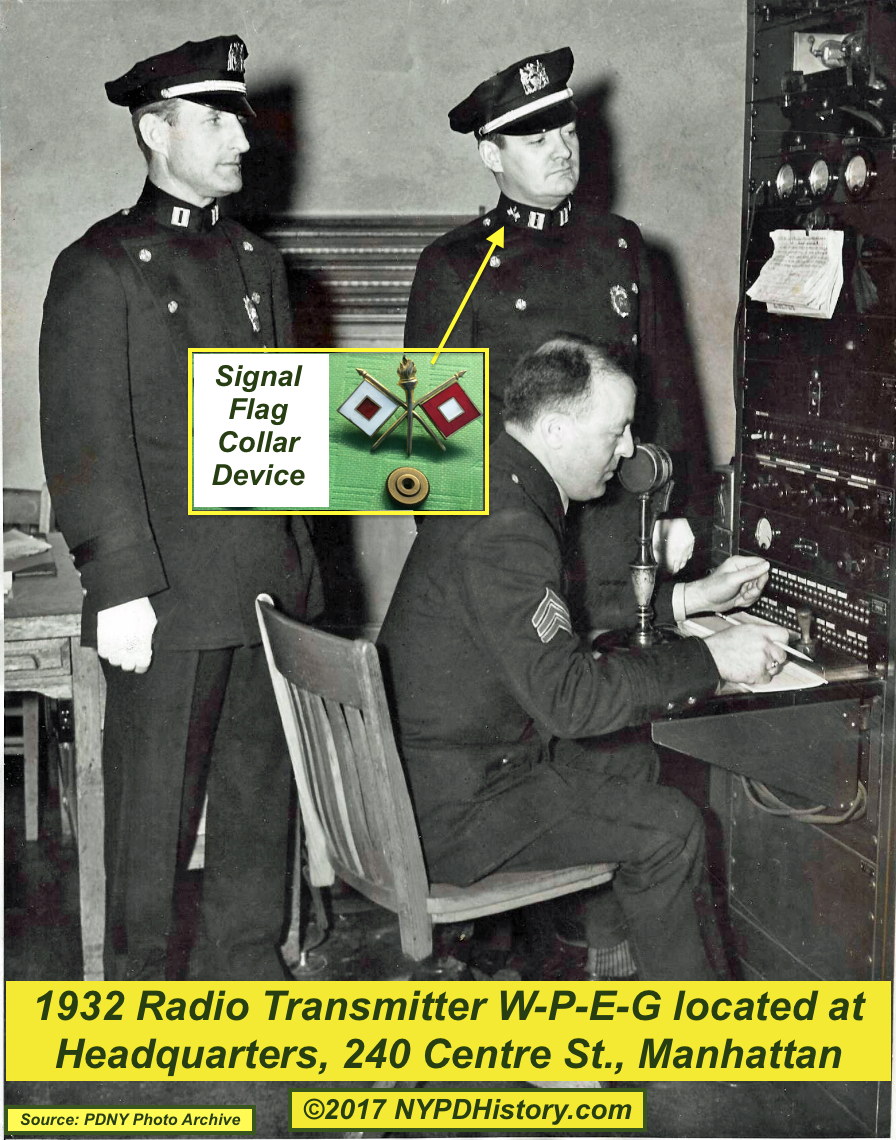

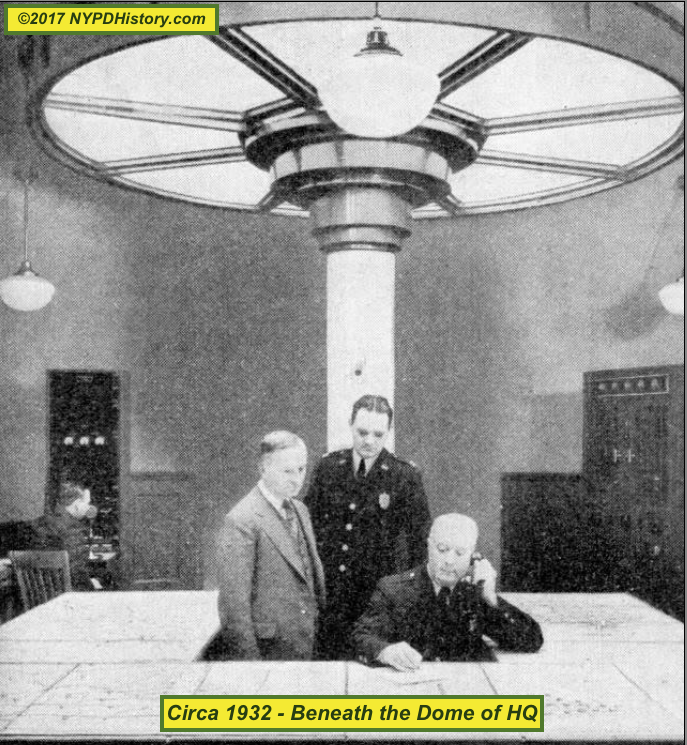

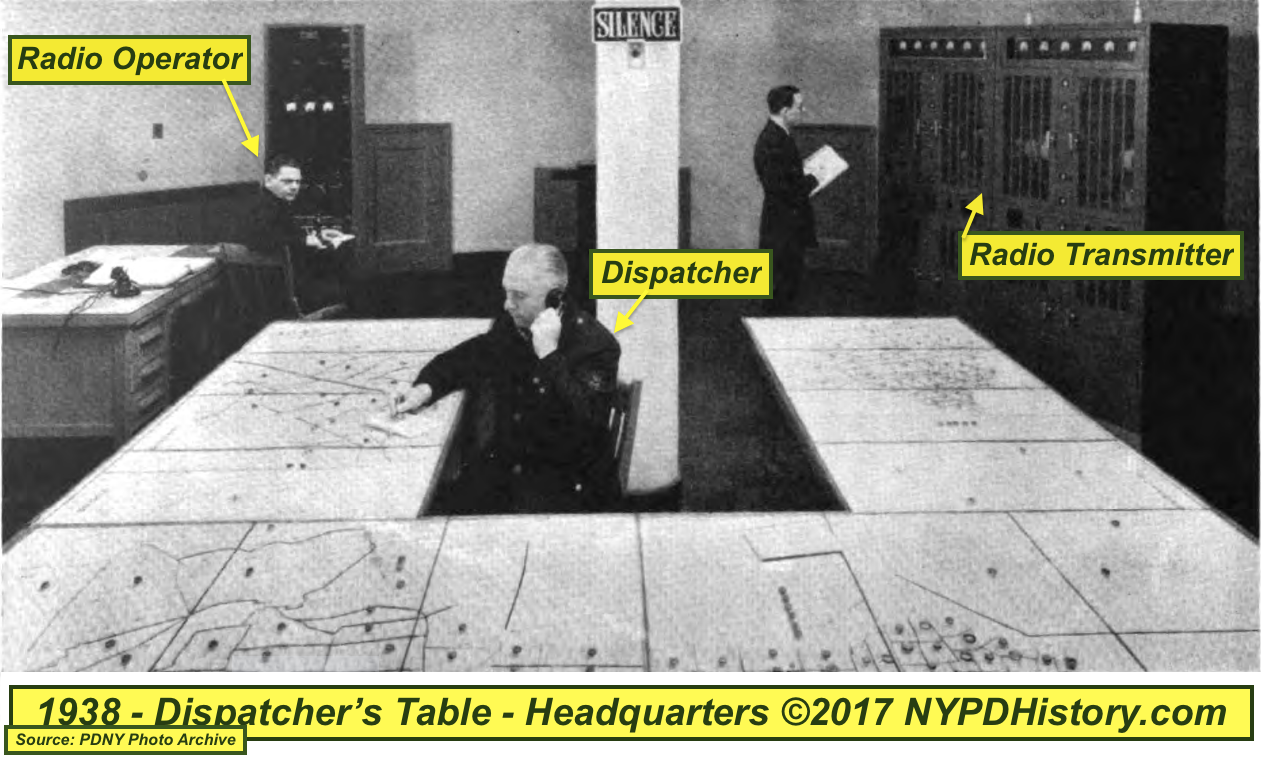

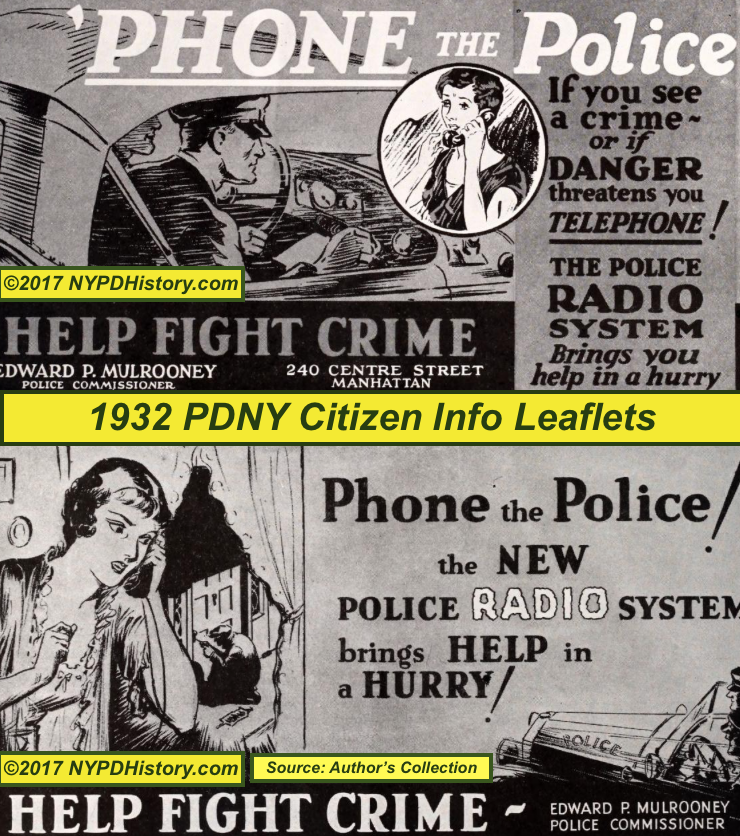

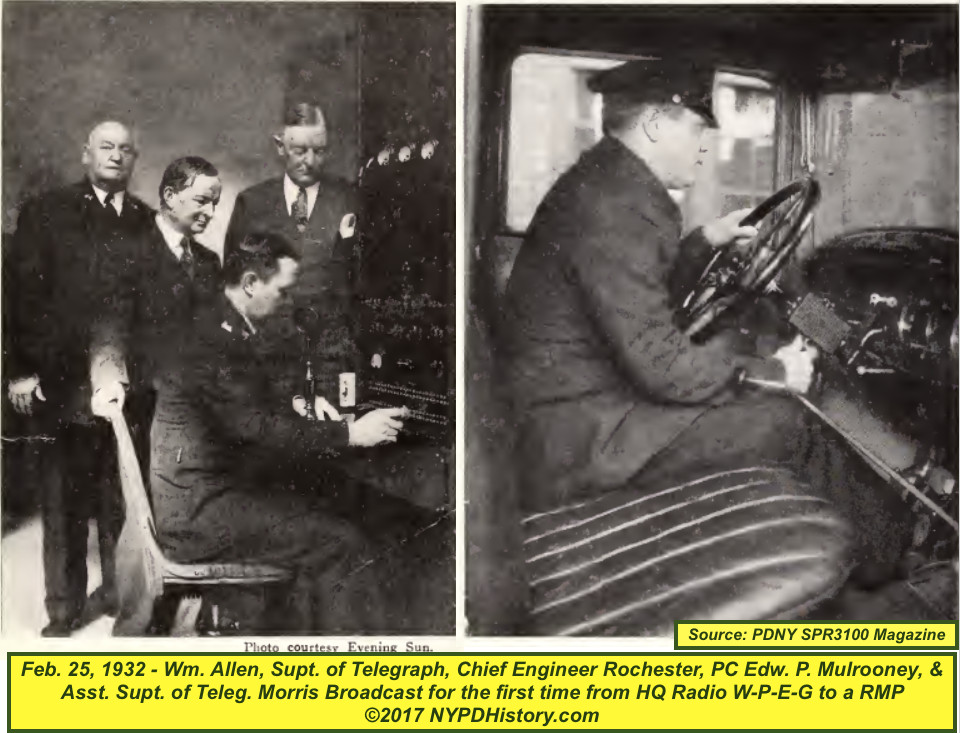

In 1932, beneath the dome of police Headquarters, the NYC PD operated a radio transmitter, using the call letter designation “W-P-E-G”. This 1,000 watt radio station was used to receive and transmit radio transmissions between headquarters and PD vehicles. On each tour of duty, the room was manned by a Dispatcher and a Radio Operator. The first broadcast was made on February 25, 1932 and was acclaimed by Police Commissioner Edward P. Mulrooney as “wonderful success.” Fifty-thousand informational leaflets were distributed to the citizens of NYC to “Help yourself by helping us” by telephoning the police who would send a RMP.

Calls for service were first received by the department’s switchboard and, in the case of a call for emergency assistance, were transferred to the Dispatcher in the radio room. On July 8, 1935, civilian switchboard operators replaced uniformed police officers.

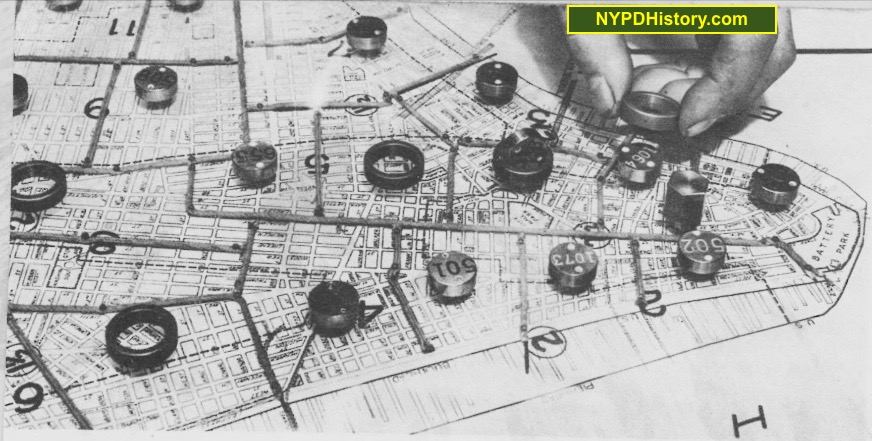

The Dispatcher sat at a “U” shaped table on which detailed maps of all of the boroughs, the confines of precincts, patrol posts, and radio patrol posts were laid under glass. The Dispatcher monitored the radio transmissions from the Radio Operator (called an “Announcer”) to the men in various vehicles, and placed color-coded markers on them reflecting the type of post, status and type of vehicle. The marker would be changed once a telephone call (either from a call box or public telephone) was received by the Dispatcher from the men in the car giving the disposition of the call. If a unit did not call in within fifteen minutes, another car would be sent to determine if the first unit needed additional support.

Two 500 watt auxiliary radio broadcasting stations were planned to be installed at the Fortieth Precinct Station-house, “W-P-E-S,” located at 257 Alexander Ave., Bronx and the Seventy-first Precinct Station-house, “W-P-E-E,” located at 421 Empire Blvd., Brooklyn. These stations were to be used in the event the main broadcast station at headquarters was out of service.

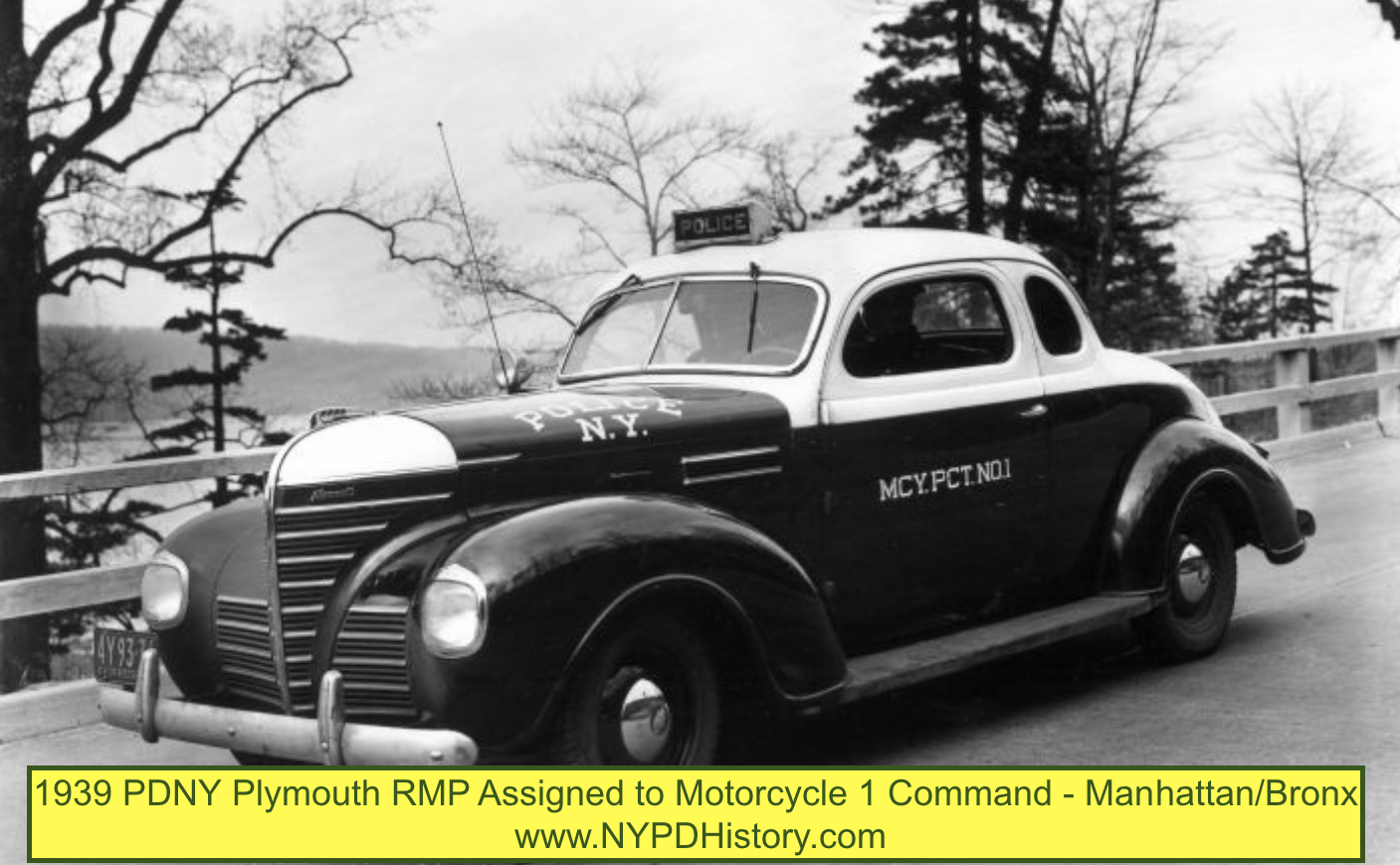

Vehicles were equipped with radio receivers (manufactured by the American Bosch Company, Springfield, MA) that occupied much of the space of the trunk of the vehicle. Inside the vehicle’s cabin, a handset, a speaker, and a small table used as a writing surface were mounted. Controls for volume and sensitivity were attached to the steering wheel column.

That same year, 1932, marked the installation of the first radio receiver in a NYC PD marked sedan, the aforementioned RMP. In September of 1933, the NYC PD hosted an Electrical and Radio Show and displayed examples of their radio equipped planes, sedans, and a debut of a radio-equipped motorcycle. By April 1934, there were 304 RMPs equipped with radio receivers. On May 3, 1934, a teletype message was sent from Headquarters to all commanding officers which praised the work of the men assigned to RMPs.

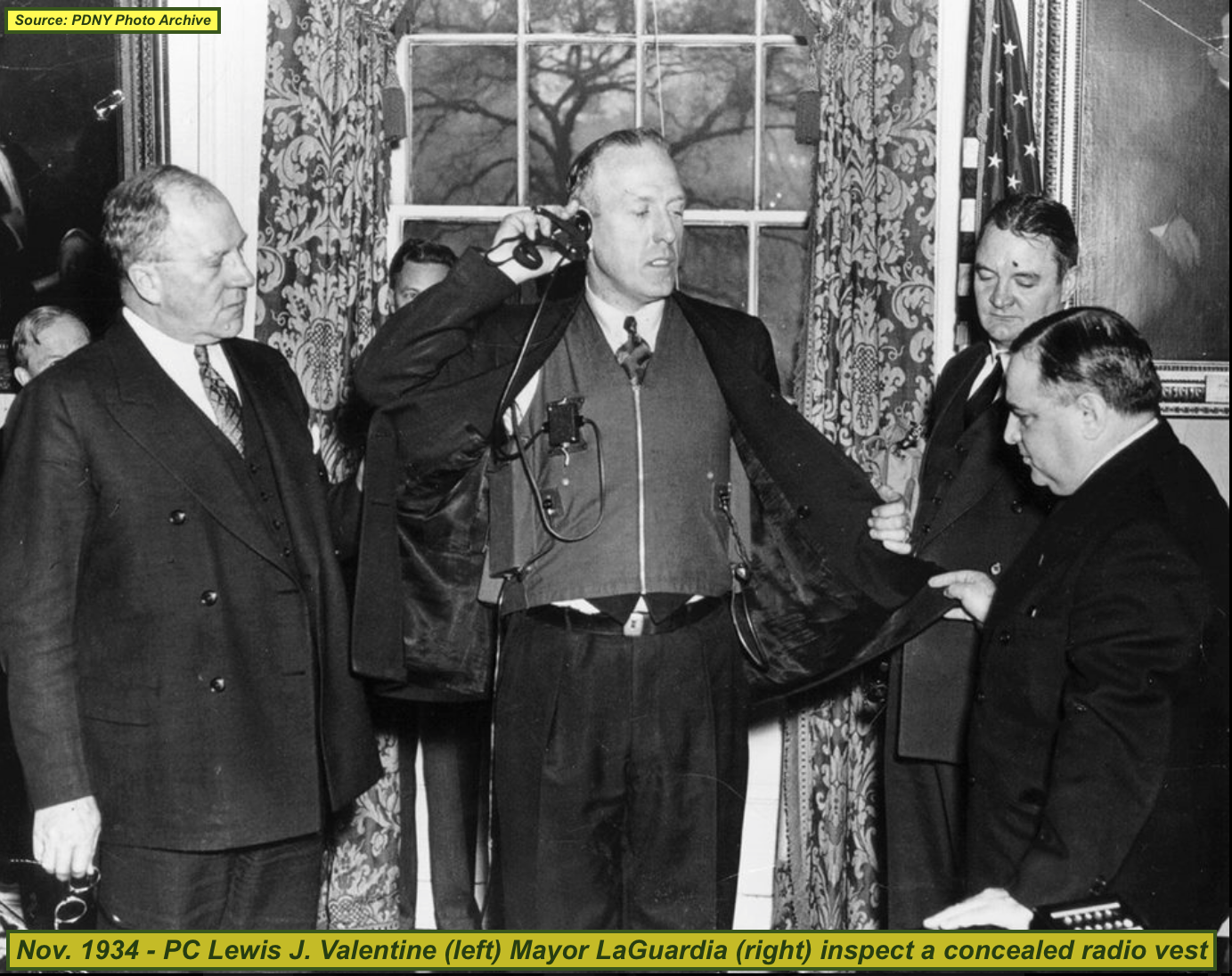

In November 1934, a 200 watt transceiver was installed on the thirty-ninth floor of the NYC Municipal Building (Manhattan side of the Brooklyn Bridge) and tests between this station and NYC police boats, equipped with fifteen watt transceivers were performed. At the same time, a short wave radio transmitter that could be concealed on a person was also tested.

In May of 1934, on the occasion of the NYC PD’s Medal Day, the proceedings of the event were broadcast to the public using a NYC radio transmitter, “W-N-Y-C.” This broadcast was the first time in the history of the city, that the event was broadcast live. PC George S. Nolan presided over the ceremony.

An article published in November 1934, relating to the services rendered by radio-equipped sedans, indicated that the NYC PD used two types of sedans, the aforementioned RMPs, and sedans assigned to the Detective District Patrol, and each type was manned by four plainclothes Detectives. These Detective cars were referred to as “Prowler Cars” or Cruiser RMPs (CRMP). Additionally, the trucks of the Emergency Services Division, established in 1930, were referred to as “Radio Emergency Patrols” or “REPs.” In addition, to the above vehicles, the NYC PD continued to utilize radio-equipped airplanes, boats, and by the third-quarter of 1933, Indian Brand Motorcycles, equipped with radio receivers.

An interesting example of the NYC PD Air Division’s use of a radio airplane to solve a kidnapping case demonstrates how important the use of the two technologies (manned flight and voice radio) were to the PD, and how innovation and quick-thinking Detectives are key to solving crime.

In 1931, the daughter of a judge had been kidnapped and held for ransom. Quite the Queens Detective District was working the case and following leads, the kidnappers had two homing pigeons delivered to the judge’s home. Accompanying the pigeons was a note to the judge demanding that he attach a ransom of $10,000 to the pigeons and set them free within seventy-two hours or his daughter would be killed.

This raised the obvious problems for the sleuths who had never before encountered such a tactic. Thinking quickly, the Inspector who was the Commanding Officer of the Queens Detectives, summoned two of the NYC PD Air Division’s aviators to his office and, working with the Detectives, a plan was formulated. The plan was to paint the pigeons’ with bright orange-colored paint, to release them once the PD’s planes were in flight above the release area, and for the planes to track the homing pigeons to their “home.”

The next morning, the plan was executed, and the planes utilized two-way voice radios to send messages to radio receiver equipped PD autos. the pigeons flew to the Flushing Heights area of Queens and the pilots observed that the pigeons landed in a pigeon coop on top of a garage. The pilots radioed the location to the autos and added that two men were observed handling the pigeons. The pilots radioed that the men got into a car and were fleeing the area. With the planes and PD autos in pursuit, the perpetrators fired a shotgun at one of the low flying planes, leaving the left wing, riddled with holes from the pellets.

The aircraft transmitted directions to all radio equipped PD vehicles in the area to set-up roadblocks in order to stop the heavily armed green Ford sedan. A Radio Emergency Patrol truck from Emergency Services blocked the fleeing auto’s path, forcing the car into a ditch. The two kidnappers were arrested and the judge’s daughter was found in a house opposite the garage and returned safely to her family.

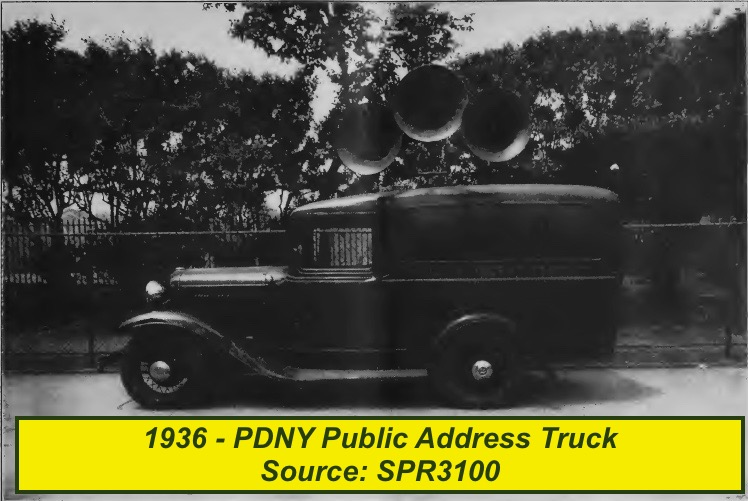

Public Address Truck

In 1936, the NYC PD Telegraph Bureau maintained a truck equipped with a public address system. The truck was used on occasions where large crowds were gathered, such as demonstrations, incidents, or at sporting events.

Despite the advances in this period from wireless telegraphy to one-way radio transmissions, the use of the telephone Signal Box remained the only method (except for the use of public telephones) for Patrolmen, on foot, horse, or in a RMP to speak with a precinct, or headquarters. The Signal Boxes were also used for hourly “rings,” as discussed in detail in Part 1 of this series.

In March 1935, a rule was issued that required Commanding Officers of precincts to publish a four day ring schedule for each RMP. The rule further required that rings from the same box were not permitted one after the other; and that RMPs remain remain near the Signal Box for five minutes after “ringing” in to the station-house.

NYC PD Tests Two-Way Voice Radios

In July of 1935, PC Lewis J. Valentine and other department officials visited the City of Boston PD, to examine the General Electric brand two-way radio system used by that department. Prior to his return to NYC, PC Valentine stated “It is one of the marvels of the age. It is the most astounding experience I ever had. I’m going to look into the two-way radio system when I get back. We haven’t anything like it in New York.” Numerous departments in other states, and the County of Nassau, adjoining NYC’s Borough of Queens, had already installed a two-way radio system and used them with great success.

Newspaper editorials echoed the PC’s position. The editors of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, on September 2, 1935, wrote “it is false economy for the Police Department not to start on the two-way system on a big scale as soon as possible.” By November 1936, 509 one-way radio equipped marked RMPs and CRMPs operated throughout the city.

The use of a wireless telegraph system continued in 1936. The system was used to communicate between entities within the NYC PD, as well as with law enforcement agencies outside of the city, within New York State, and beyond.

Early in 1936, Superintendent of the Telegraph Bureau, Captain Gerald S. Morris and two “patrolmen-scientists,” (Charles Francis and John Mulvihill) began experimenting and testing two-way radio equipment. A transceiver (transmitter/receiver), operated under license by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), designated with the call sign “W-P-E-F,” was installed at headquarters. Additionally, a mobile transceiver was installed in an automobile. Tests were conducted from various points in the city and, as part of the testing, the car was deployed for use at the July 11th opening ceremony for the Triborough Bridge, which was attended by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The procession then travelled up the Grand Concourse in the Bronx.

After the test, Captain Morris, prophesied that the ability for headquarters to communicate two-ways with vehicles would be the next revolution in police communications and in police work itself. Capt. Morris stated “If television is practically around the corner, can two-way radio be far behind?”

According to an article published on August 16, 1936, in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Capt. Morris had recently installed two-way radios in three Brooklyn-based sedans that communicated with headquarters in Manhattan. The cost of the February 1932 system, which consisted of three base stations and 590 automobiles, was $100,000. Capt. Morris projected that if he could find a two-way radio system capable overcoming the technological limitations met due to the density of high rise buildings, the cost of equipping the 590 RMPs would be approximately $350,000.

One year later, in November 1937, Capt. Morris addressed the attendees of the New York State Association of Chiefs of Police. Capt. Morris reported that the NYC PD had experimented with two-way radios for eighteen months and projected that, within six months, the NYC PD would deploy the same in motor patrols citywide. History will show how far off he was with his projections.

The risks inherent in responding in a RMP quickly became evident. The number of collisions, some of which were fatal, prompted the promulgation of what appears to be the first NYC PD General Order (G.O.) addressing this risk. In November 1938, PC Lewis J. Valentine issued G.O. 27. The order described how four Patrolmen, assigned to RMPs, recently lost their lives as a result of RMP collisions. These Patrolmen were: Victor Cooper and his partner Clarence Clark, and Angelo Favata and his partner Arthur Howarth. PC Valentine used the words “Better to Arrive a Minute Late Than Not to Arrive at All” to remind officers about the inherent danger of a collision. To this day, as a reminder to all officers to drive safely, the NYC PD uses the two words “Arrive Alive!” to remind officers of the danger.

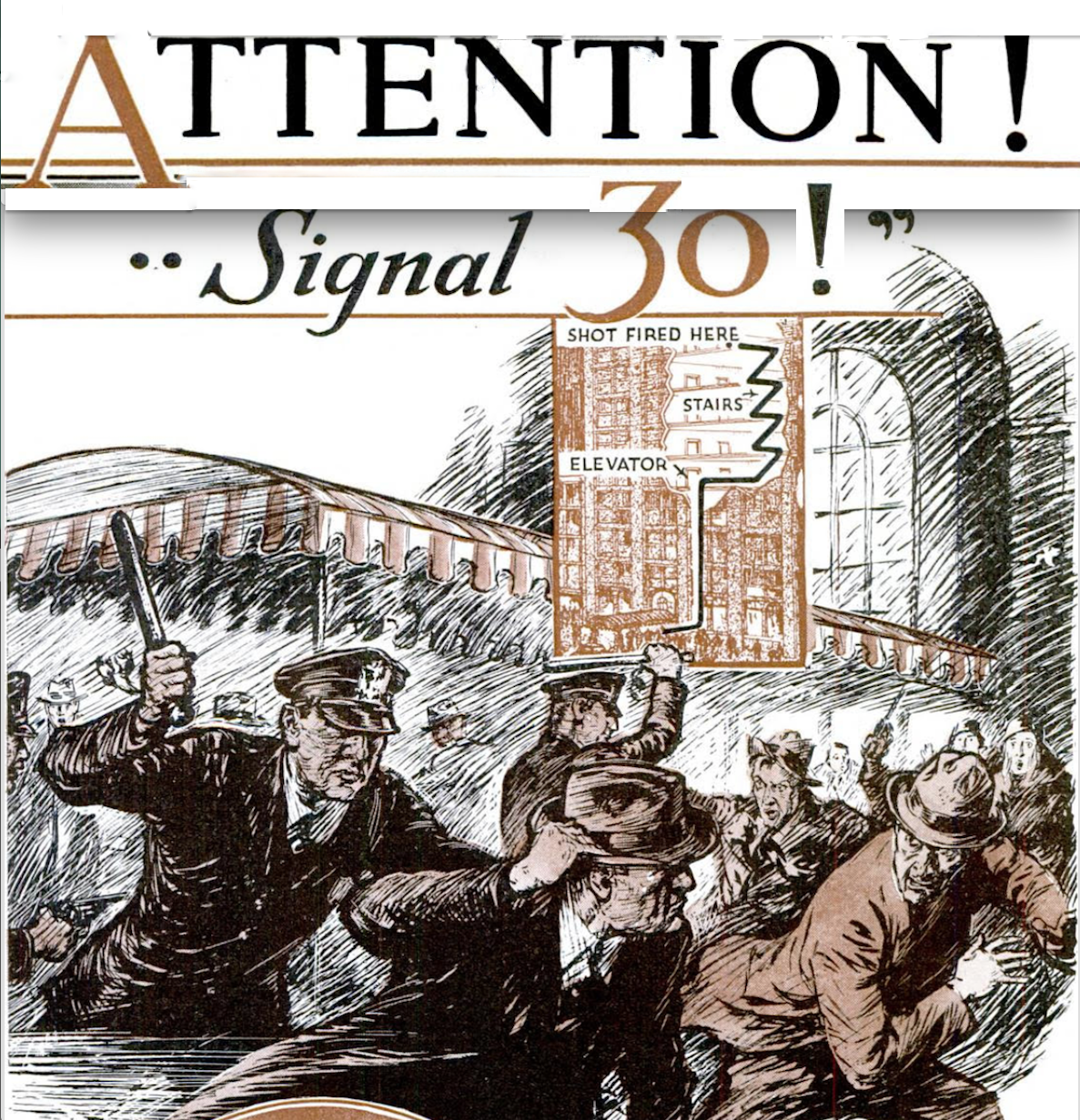

The Manual of Procedure (MOP) of the NYC PD (1937 Revision) addressed in great-detail the responsibilities of officers, and their supervisors, in the maintenance and operation of RMPs and the radio equipment installed therein. Excerpts of interest are: RMPs within a five block radius of a radio call were to respond to any calls heard over the receiver; one officer must remain in the RMP while the other was on meal break; and all dispatches were to be recorded verbatim by the “Recorder” (passenger) of the RMP. In the section dealing with the Telegraph Bureau, the MOP contained the “Signal Code” which was to be used by the Bureau when sending out teletype messages and alarms. A “Signal 30” was a call for “Officer Needs Assistance,” the equivalent of todays Ten Code, “10-13.”

In 1938, there were a total of 671 radio-equipped vehicles in the NYC PD, 424 of which were radio-equipped cars on patrol during each of the three tours per day. These radios were operated in the “Low Band Range.” The car antennas were the large eight foot ball and whip style. Eleven police boats were equipped with radios.

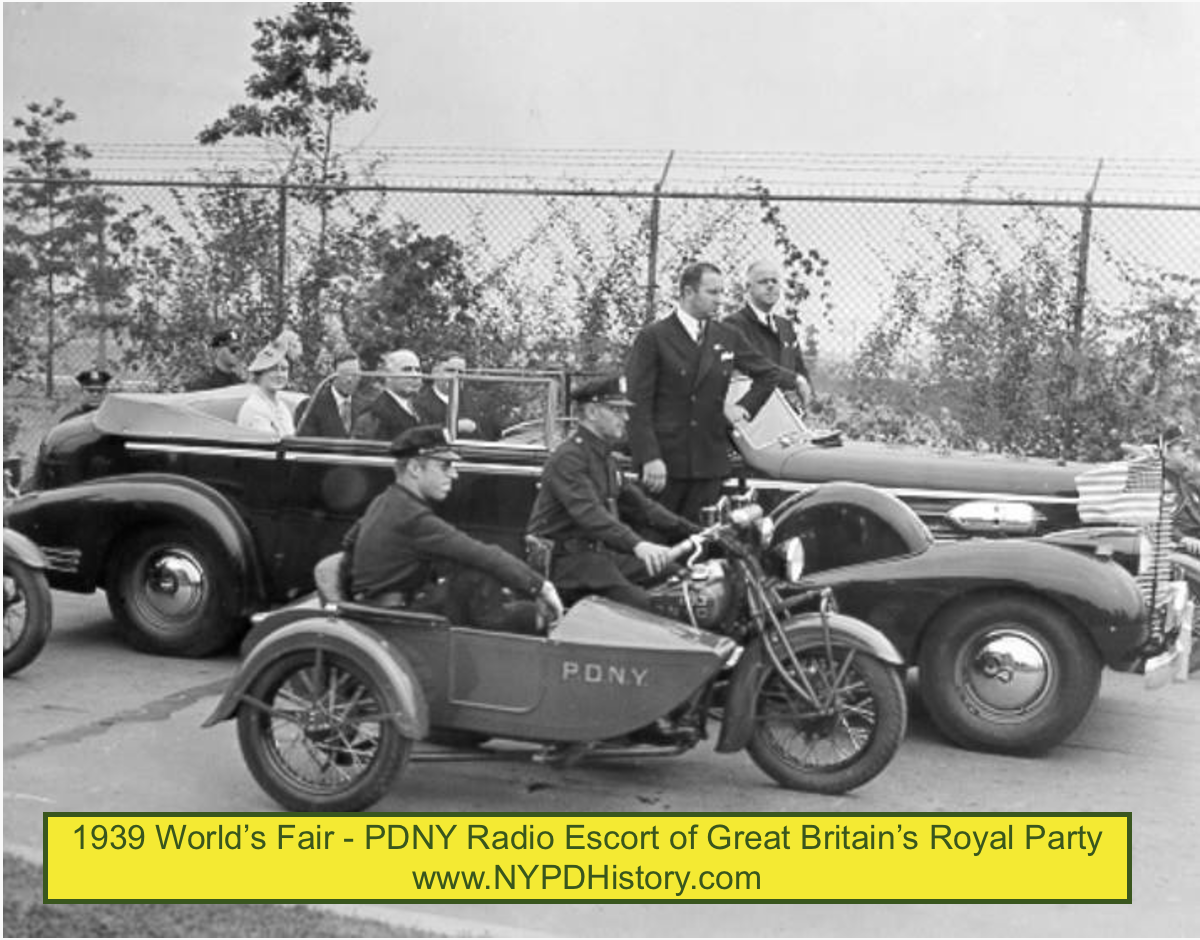

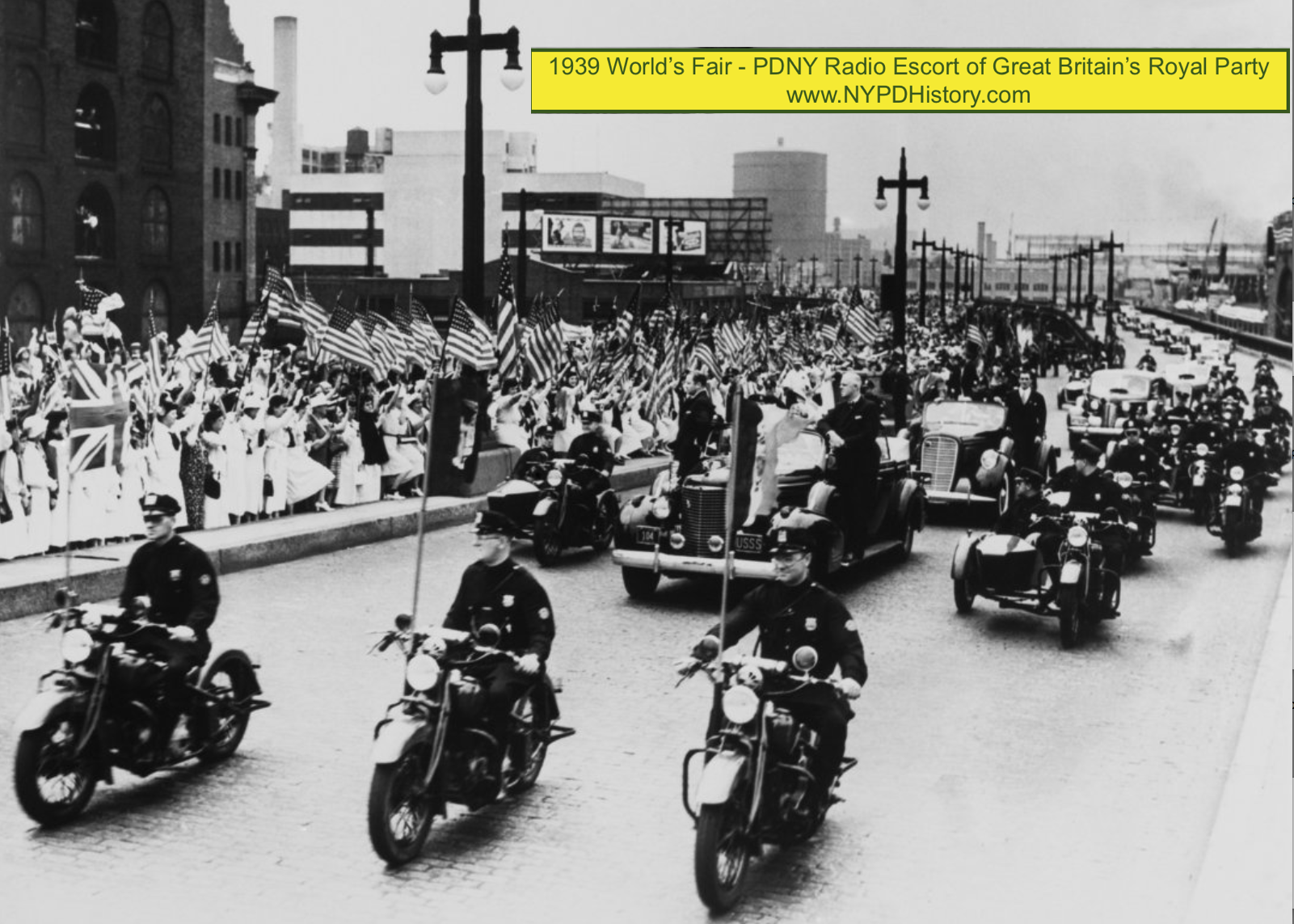

The 1939 World’s Fair, held in Queens, New York, was an exhibition of future innovations presented by various countries. It was fitting, therefore, that the NYC PD would take the opportunity to test the two-way radio at the Fair. In an article published on June 11, 1939, The New York Times reported, that the NYC PD utilized two-way radios to coordinate the PD’s coverage of the arrival of a contingent of the members of Great Britain’s “Royal Party.” The Party arrived at a Manhattan dock in a destroyer class ship, and a NYC PD Harbor Unit Launch (class of boat) notified police headquarters via two-way radio. Headquarters then notified, via two-way radio, a temporary police headquarters at the 110A Precinct, just outside of the main gate of the Fair. Three RMPs equipped with two-way radios were used to escort the royal party to the fairgrounds and inside the fairgrounds, two patrolmen using a portable two-way radio communicated the party’s movements to the temporary headquarters.

The Advent of the NYC PD’s Adoption of Two-Way Radio Communication

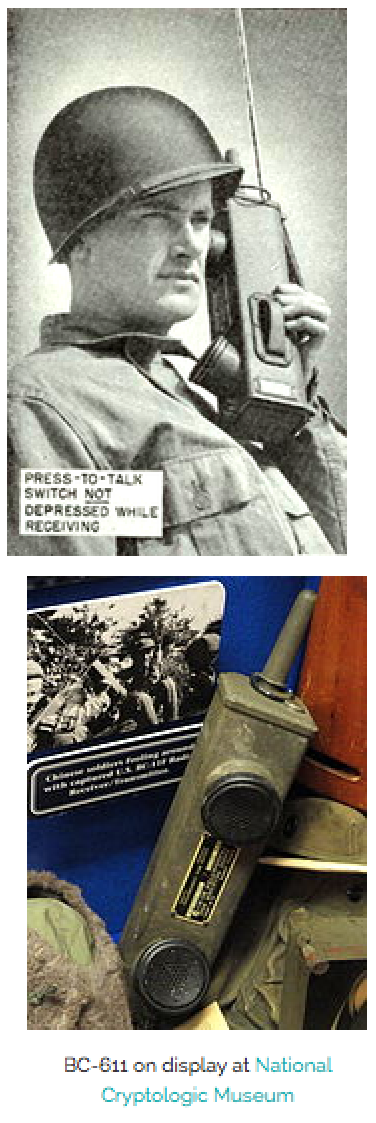

It appears that the while nation’s efforts during, and immediately following World War II (1939-1945), stalled the NYC PD’s plans to research, experiment with, and widely adopt two-way radios. Additionally, the technical challenges in overcoming the density of tall buildings in Manhattan using Low Band frequencies were cited as a factor in the delay. WWII, however, resulted in new radio technology, particularly non-vehicle two-way radios.

In 1940, during World War II, a “Handie-Talkie,” transceiver (two-way voice radio) manufactured by Galvin Manufacturing, was adopted by the U.S. Army Signal Corps. This familiar design was officially known as the SCR-536, was carried into battle on Omaha Beach and Normandy in June 1944. nearing the war’s end, Motorola had acquired Galvin, and 130,000 handle-talkies were in use by the armed forces.

During the War, the NYC PD’s transceiver technology would not change significantly. It would not be until after WWII, that in 1946 two-way radios were widely adopted by the NYC PD.

Capt. Morris’ prophecies, predictions, expectations and dreams would not be realized during the Pre-War period. While one-way transmissions were a great advance in technology, a revolution in communications, and an irreversible advancement to police work itself, the disadvantages were obvious when compared to two-way radio communications.

In the post-War period, the NYC PD would finally begin to make headway in realizing a true, modern, two-way voice radio system.

To read Part 3, Click Here

========================

Feel free to use the “Contact Us” box on the website to submit questions, comments, corrections, and constructive criticism.

We’d like to thank those individuals who have shared their photos and anecdotal stories from this period with us! Your kind words of support are appreciated!

Please feel free share the link to this article in any police, PDNY or NYPD history-related or other group on Facebook.

![]()

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.