Introduction:

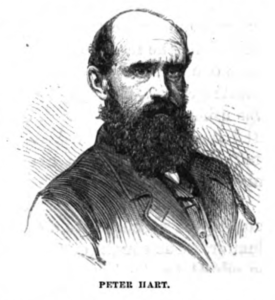

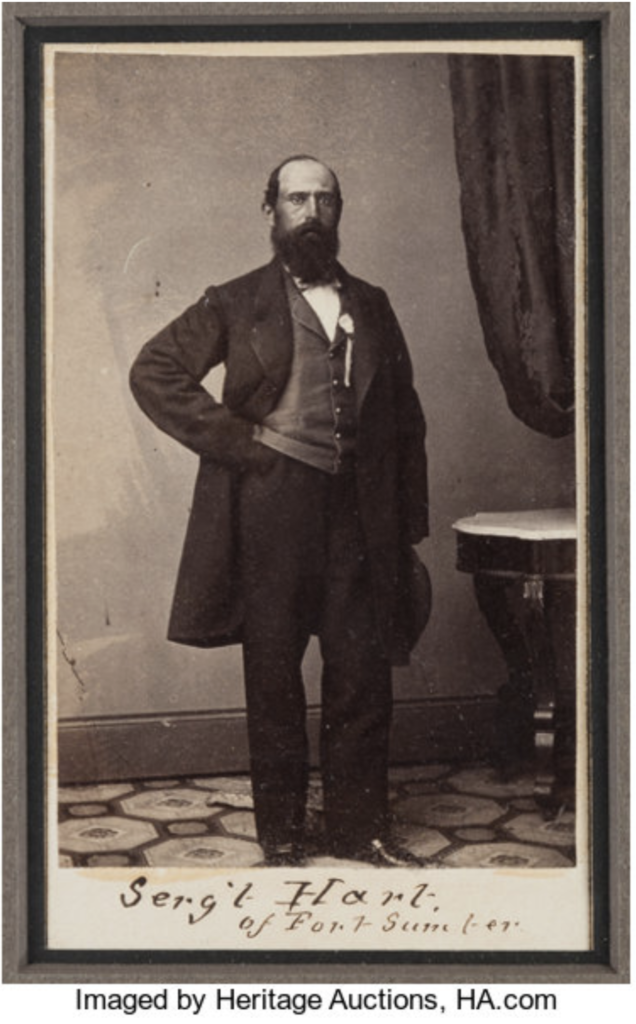

This is the story of the heroic action of New York City (NYC) police officer, Patrolman Peter Hart, who was a veteran soldier, and whose name was known to every American as a National Hero for having played an integral role in the first battle of the Civil War. The heroic act that he performed caused the patriotic, enthusiastic support for the United States during the war, and beyond. Unfortunately, with the passage of time, his name, and the act he performed, has escaped police historians and the Police Department of the City of New York.

The time has come to shed a bright light on this gallant, trustworthy, and faithful officer’s story.

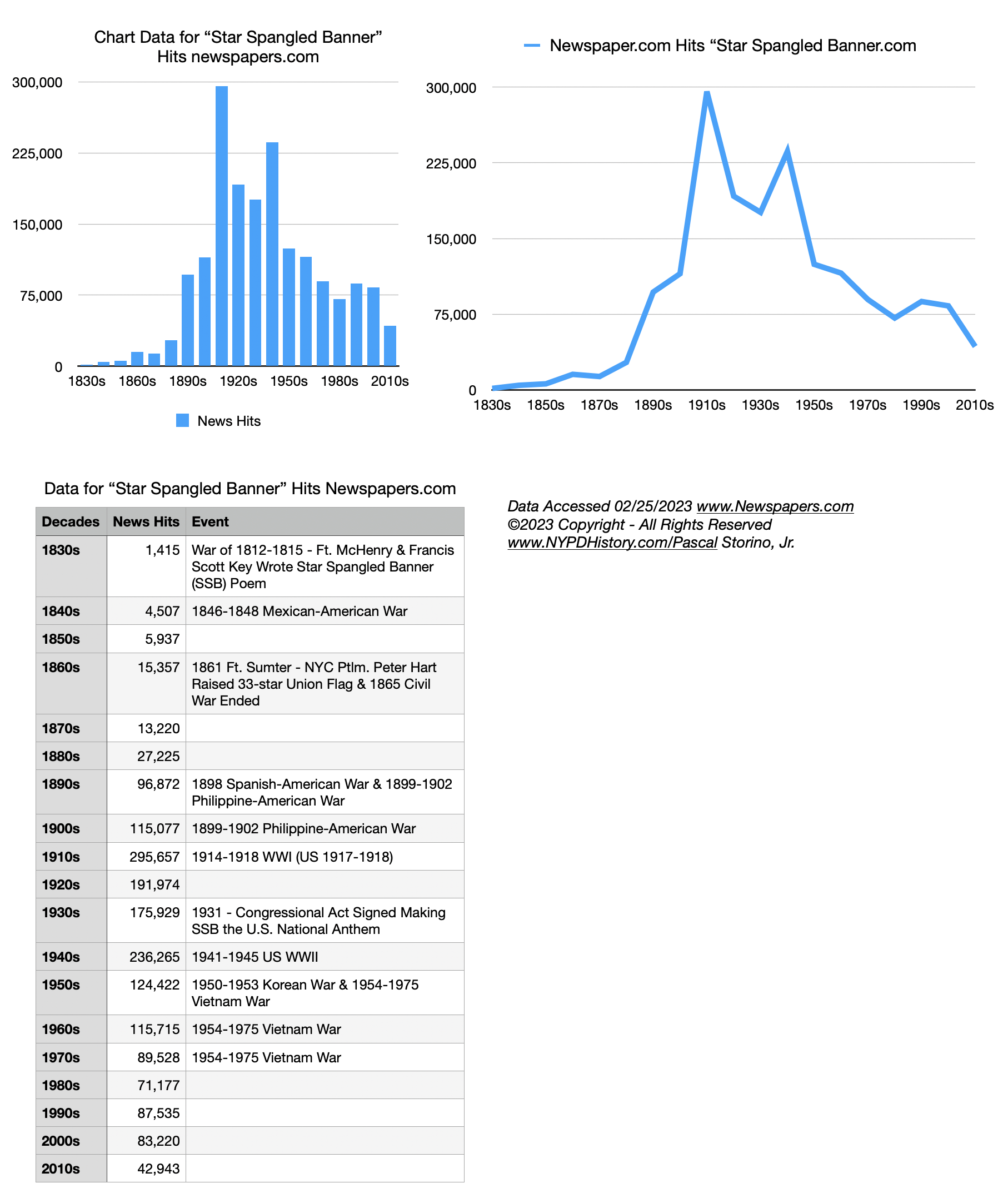

How many Americans know the history and meaning behind the National Anthem (“The Star Spangled Banner”) and its lyrics? “The Star Spangled Banner,” was written by Francis Scott Key, in 1812, after he witnessed the British attack on Fort McHenry, Maryland.

Few are aware that the song’s popularity, as a patriotic standard, rose greatly, during the Civil War, after the opening of hostilities at Fort Sumter, Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. It was at Fort Sumter in 1861 that the 33-star American Flag was shot down by Confederate troops and re-hoisted by a Veteran of the Mexican War (1846-1848), who became a national hero. The similarity in the circumstances between the British bombardment of Fort McHenry in 1812 and that of the attack on Fort Sumter in 1861 did not escape notice at the time.

Both flags, the Star Spangled Banner Flag of 1812 and the 33-star flag of 1861, endured concentrated, sustained bombardments which attempted to destroy the same, but they held fast. This led to the decades-long rise in popularity of the song.

After the close of the Civil War in 1865, the song became a favorite with the military, and was played/sung at official ceremonies and events. Three decades later, it had been officially designated by the military as the song to be played at functions and flag ceremonies. Citizens followed the lead of the military, advancing the song becoming the national standard.

In 1931, Representative J. Charles Linthicum, of Maryland, authored a bill which was passed by congress, signed into law, and ‘The Star Spangled Banner” officially became the National Anthem.

Background:

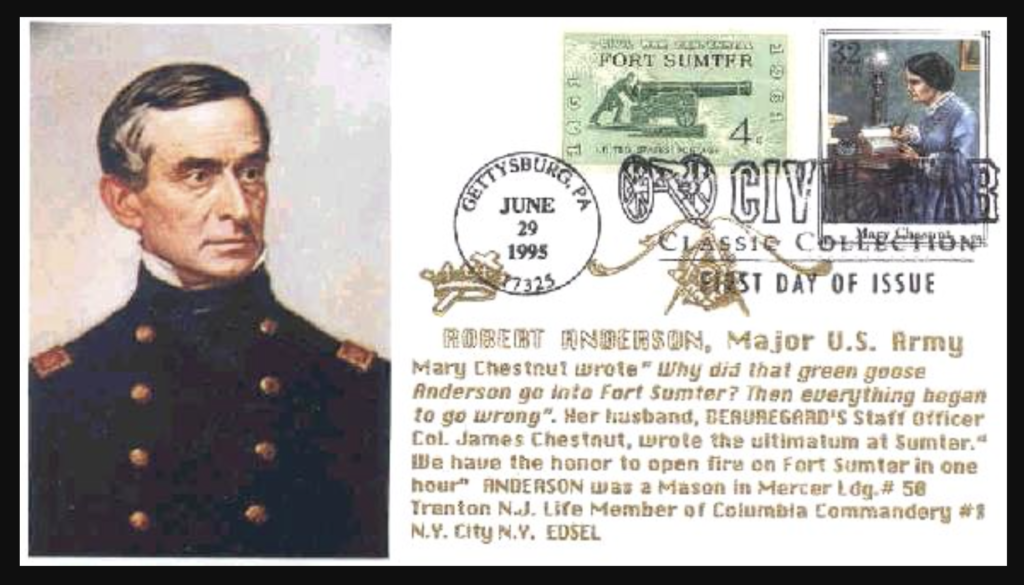

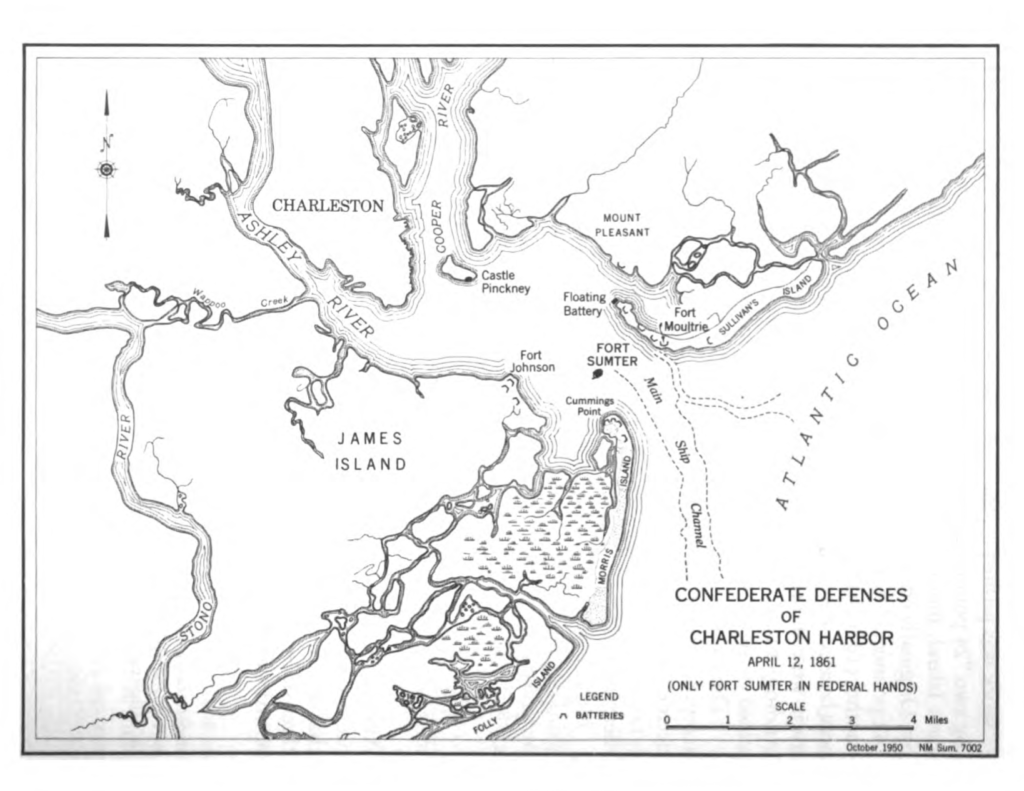

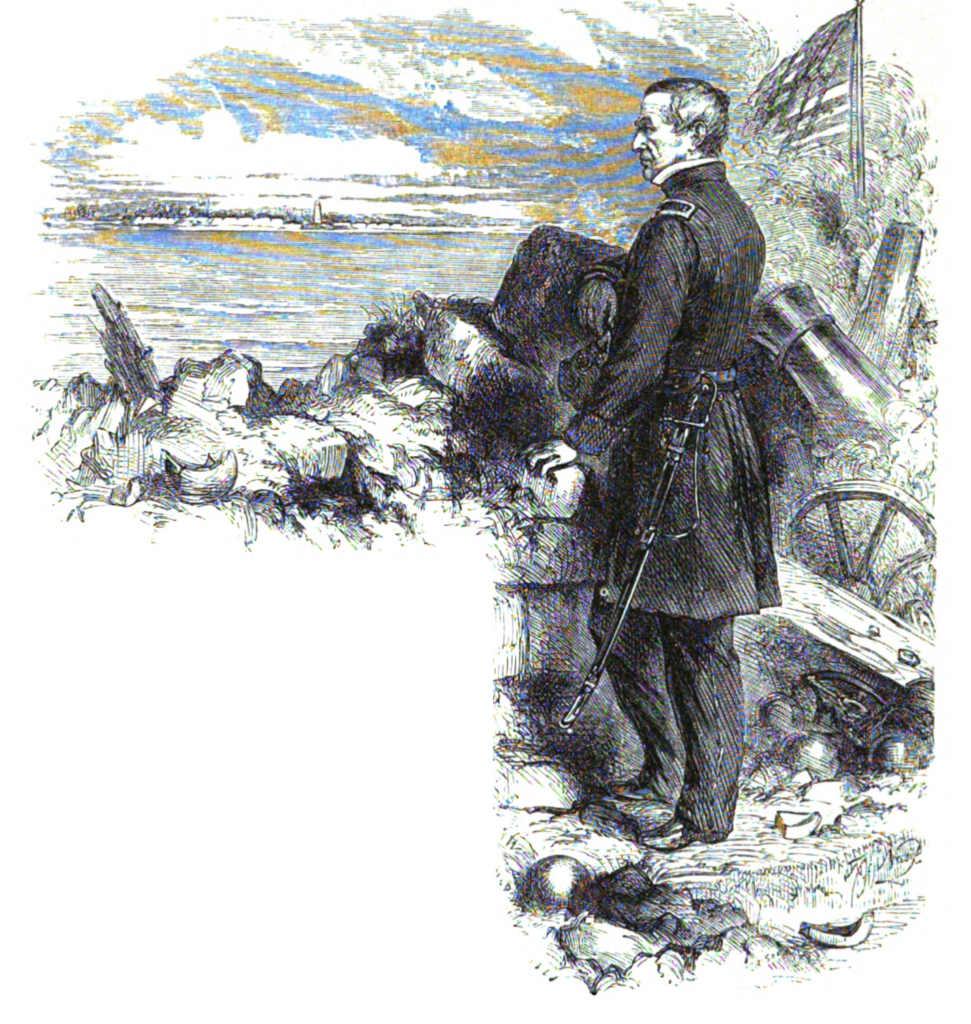

Fort Sumter is located off the coast of South Carolina in Charleston Harbor. Built in 1829, it served as a garrison (a fort where troops are stationed) for the United States of America (USA). In December 1860, South Carolina announced its secession from the Union (USA). This action initiated a standoff between the military forces of the Union and the rebellious forces of South Carolina. Major Robert Anderson, of NYC , born in Kentucky (a Confederate State) was the commanding officer of nearby Fort Moultrie, but “deemed the Fort untenable by his small force, evacuated it, and raised the” flag above Fort Sumter, Dec. 27, 1860.

Prior to the outbreak of hostilities, the newspapers of NYC published daily reports of the growing tensions between the USA and the states seeking to secede to become the Confederate States of America. Major Anderson’s wife, Mrs. Eba Anderson, was not in good health and desperately sought to travel to Fort Sumter to be with her husband.

Knowing the perils she would face, Mrs. Anderson sought out the Major’s most trusted confidant and loyal friend, to accompany her on the trip; Patrolman Peter Hart, of the Metropolitan Police Department of the City of New York, who was appointed as a Patrolman on January 26, 1860. Hart immediately agreed to escort her to Fort Sumter. Hart was no stranger to war, having served gallantly in the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) as an enlisted First Sergeant in the United States Army under Major Anderson.

Both Peter Hart and Robert Anderson were Freemasons and members of Masonic Lodges in NYC, and NJ, respectively.

On January 7, 1861, against the advice of her doctors, they began their journey and arrived in Charleston, forty-eight hours later. Before Hart was allowed to continue on the last leg of the journey, a boat ride to Fort Sumter, he had to swear to Confederate troops that he would be a non-combatant. Major Anderson was pleased to see his wife and his old aide, Sergeant Hart.

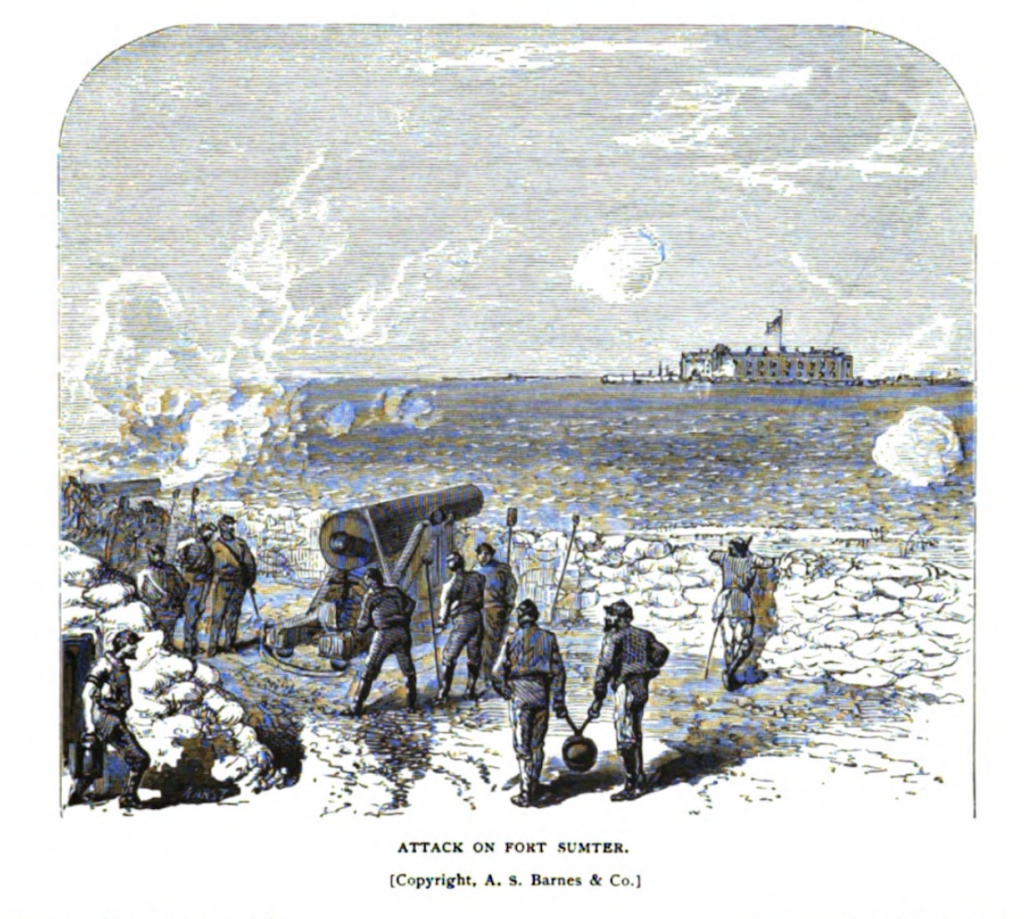

On April 12, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln announced that he intended to reinforce Fort Sumter with manpower and supplies. This resulted in the initiation of a thirty-four hour siege by Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard, of South Carolina, on Fort Sumter. The first shots of the Civil War had been fired. April 12, 1861, is one of those days that live in infamy. The Civil War had begun.

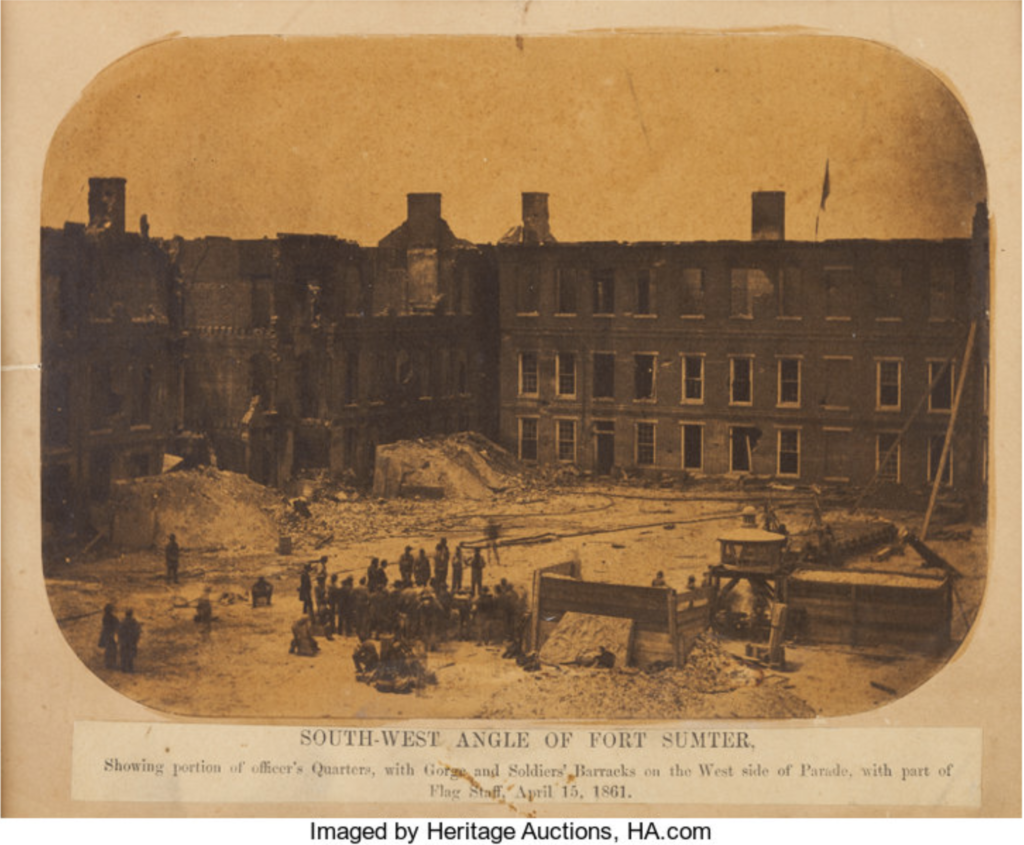

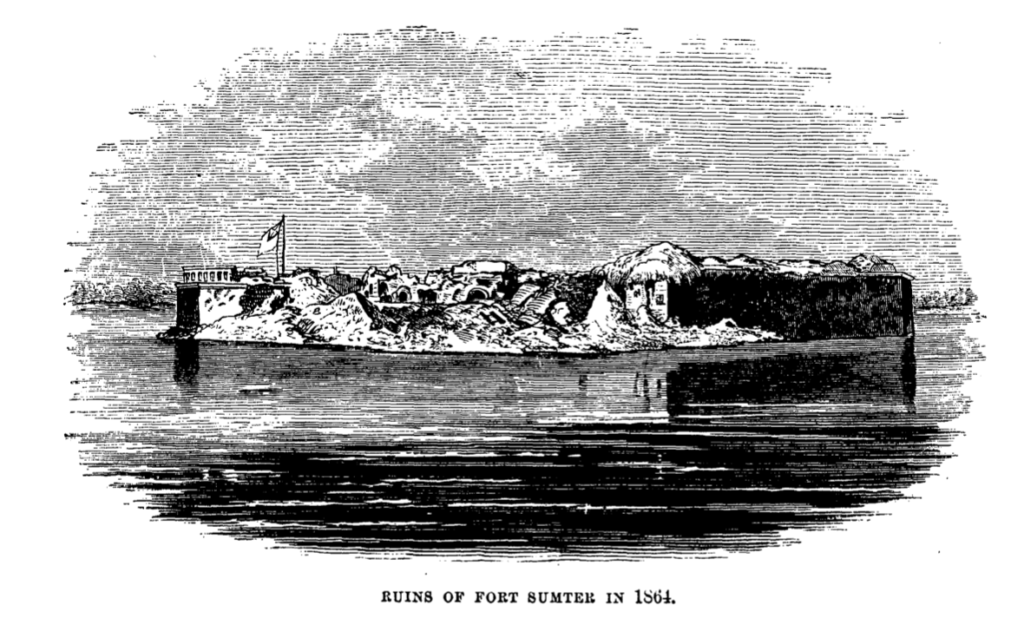

Seven forts and naval vessels fired over 3,000 canon and artillery rounds at the Fort. Major Anderson directed his men to remain in bomb-proof shelters during the heaviest part of the attack, minimizing casualties. The Fort, however, sustained major damage and fires were widespread.

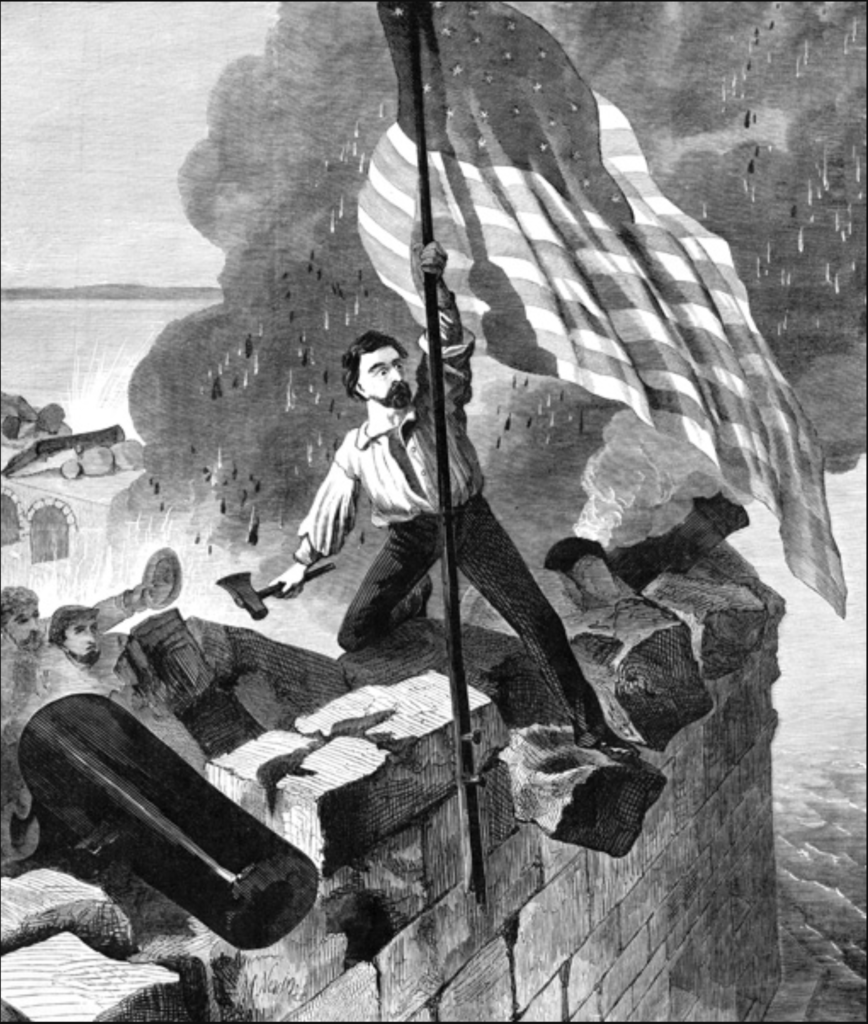

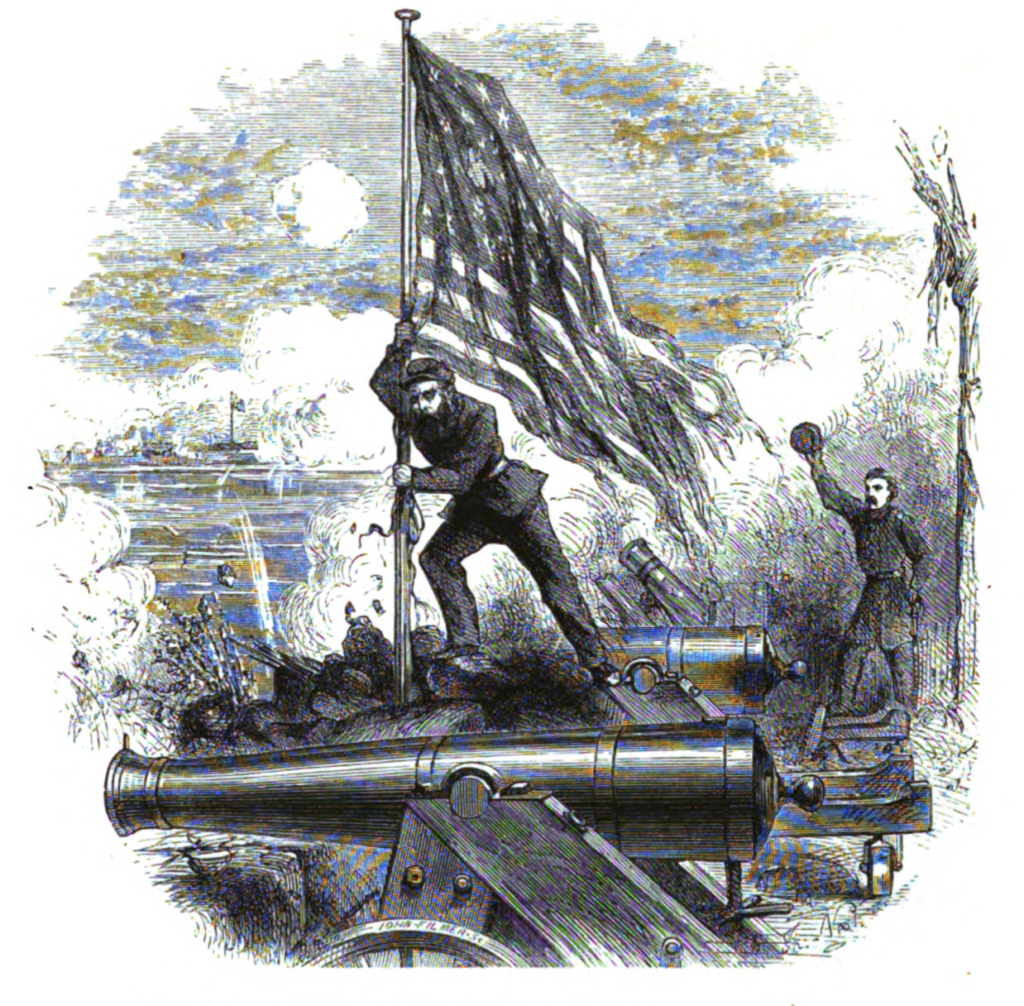

During the exchange of fire, the 33-star flag, was struck by Confederate fire nine times. At 12:40 pm, on April 13th, the ninth ball struck the flag’s mast, causing it and the flag to fall to the ground amongst the burning embers and hot metal.

The 33-star flag was also referred to as the “33-star Union flag” or “standard,” “The Fort Sumter Flag,” and the “33-star American Flag.” The stars were arranged in a diamond pattern.

By all accounts, the non-combatant, non-enlisted soldier (civilian), NYC Patrolman, Peter Hart, took immediate action. His actions are described in the following account:

“When, in the thickest of the fight, the flag was finally shot down, after having been hit nine times, Hart volunteered to raise it again, and, climbing a temporary staff, amidst a blinding hail of shot and shell, nailed the torn banner fast, and descended in safety.”

Despite concentrated fire to destroy the flag, it remained hoisted until the evacuation of the fort, on April 13, 1861, a source of consternation to the enemy and pride to Union troops. It was noted in one detailed account of the act that “Almost eighty-five years before, another braved patriotic Sergeant (William Jasper) had performed a similar feat, in Charleston harbor, near the spot where Fort Moultrie now stands, One was assisting in the establishment of American nationality, the other in maintaining it.”

The following is the first of four verses of “The Star Spangled Banner,” written by Francis Scott Key about the 1812 attack on Fort McHenry. The words may just as well have been written to describe the actions of Peter Hart, resulting in the aforementioned contemporaneous comparison, and rise in popularity at the time of, and after, the Civil War.

“O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hail’d at the twilight’s last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight

O’er the ramparts we watch’d were so gallantly streaming

And the rocket’s red glare, the bomb bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there,

O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

To read the four stanzas of the Star-spangled Banner, click here. (A new browser window will open.)

The Evacuation of Fort Sumter:

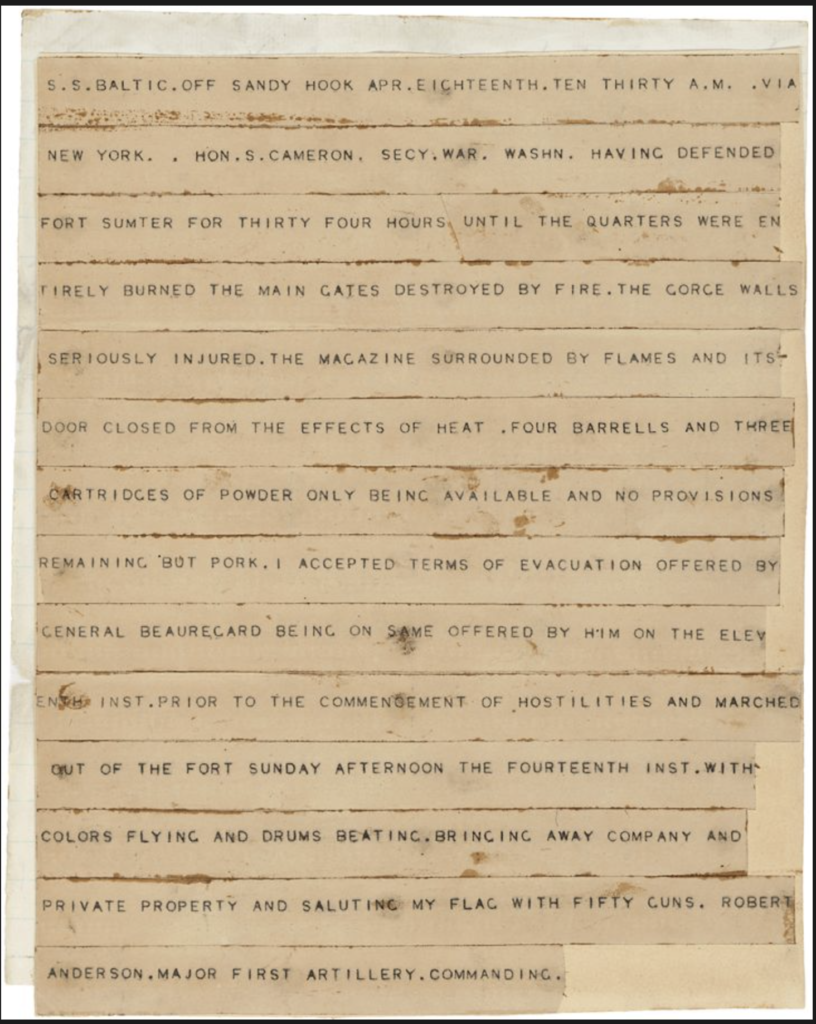

Major Anderson, assessing the heavy damage, the extremely limited amount of food and munitions, and the lack of direction from Washington, D.C., concluded that the eighty-six men under his command could not sustain the brutal bombardment. Anderson’s men were less than ninety in number. The Confederates were 3,000. The defense of the fort was unsustainable.

Despite repeated efforts by Major Anderson to communicate the same to Washington, D.C., he received no direction. Inexplicably, the Union troops observed Union Naval vessels beyond the sand bar, but they did not aid Major Anderson during the battle.

The evacuation of Fort Sumter was negotiated between the sides. Major Anderson raised the battle-torn flag for the last time.

The following is the Telegam sent from Maj. Anderson at Ft. Sumter to Secretary of War Simon Cameron regarding the surrender of, and withdrawl from, Ft. Sumter.

During the withdrawl, fifty ceremonial rounds of cannon were fired by order of Maj. Anderson to honor the American Flag and Union troops. In full uniform, the troops marched out of the fort to a waiting ship in the harbor. “Yankee Doodle” was played by the band, and at the passing of Major Anderson, “Hail to the Chief” was played. When the last troop left the fort, the Confederate and Palmetto (South Carolina) flags were raised where the 33-star flag once flew.

So ended the first battle of the Civil War and, and so began the legacy of NYC Patrolman Peter Hart as a National Hero.

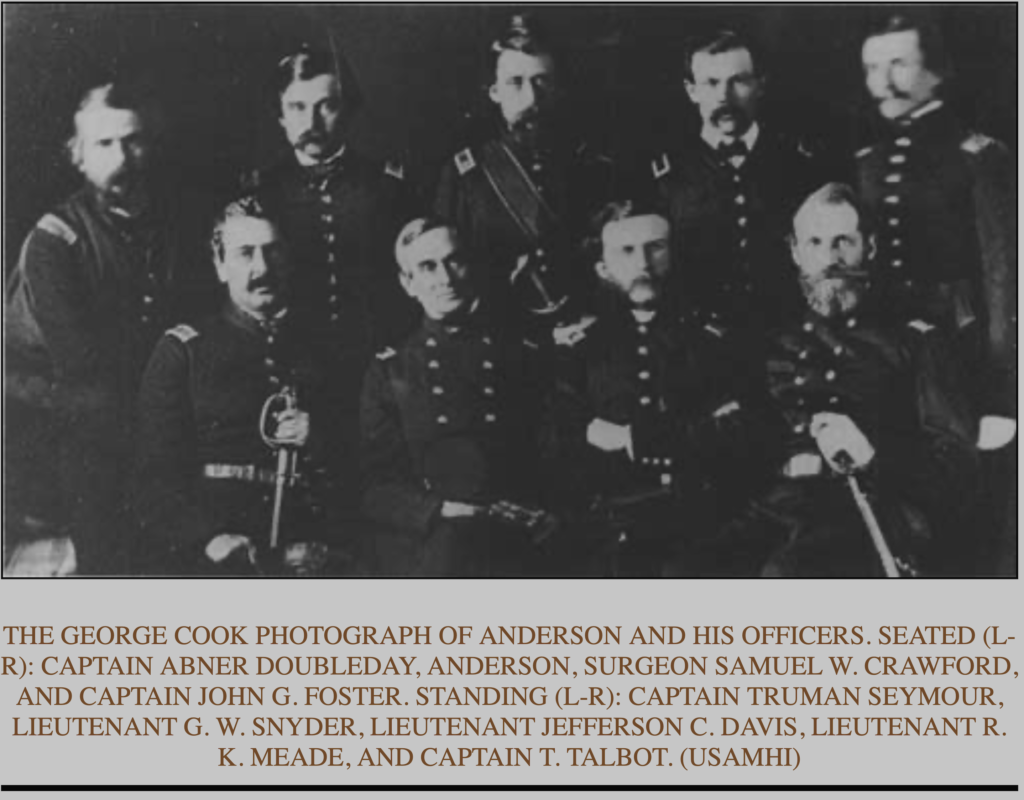

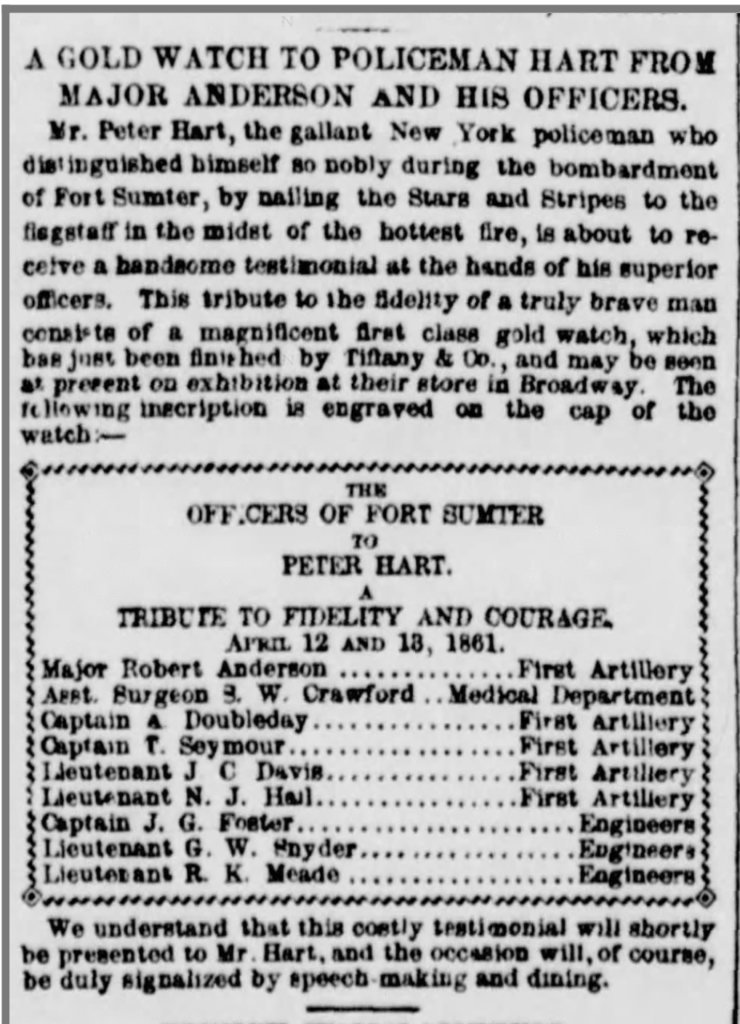

The following men were under the command of Maj. Anderson at Ft. Sumter. Note that one of the offiers was Abner Doubleday, who not only fired the first shot in defense of Ft. Sumter, but is credited as the creator of the Nation’s National Pastime, Baseball!

The men of the garrison boarded the USA Ship Baltic for the return to NYC. As the Baltic prepared to leave Charleston Harbor the insurgent soldiers, showing their respect for the gallantry of the Union troops in battle, “stood on the beach with their uncovered heads, in a token of profound respect.”

When the Baltic left the harbor, “the precious flag, for which they had fought sough gallantly, was raised to the mast-head and saluted with cheers, and by the guns of the other U.S. vessels in the little relief squadron. It was again raised when the Baltic entered the harbor of New York, on the morning of the 18th, and was greeted by salutes from the forts there, and the plaudits of thousands of welcoming spectators.”

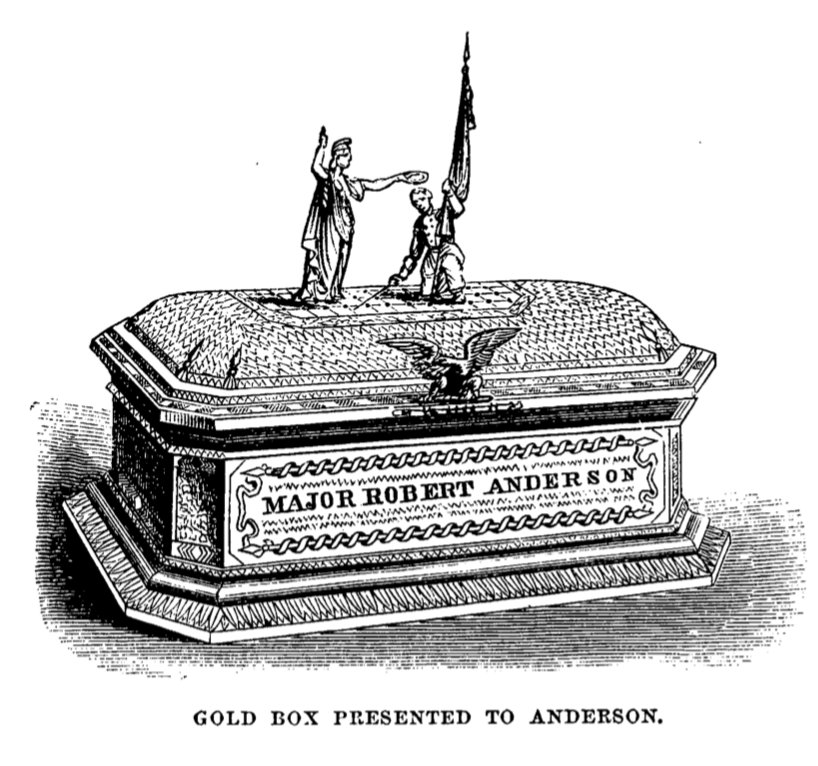

On behalf of the citizens of New York, Major Anderson was presented with “the freedom of the city” in an “elegant Gold Box, in the form of a casket, oblong octagonal in shape by military authorities. The citizens of New York also presented him with a 2 ½ inch table medal.“

The citizens of Philadelphia presented him with a beautiful sword, the handle of carved ivory.

The 33-star U.S. Flag, Major Anderson, Peter Hart, and the Troops’ Homecoming in NYC:

On April 20, 1861, Major Anderson, Mr. Hart, and members of the garrison arrived in NYC. A “monster rally” of approximately 100,000 people was held in Union Square to celebrate their arrival. The assembly was called the largest gathering to date.

During the trip to NYC, Mr. Hart had in his possession the flag flown at Fort Sumter. Upon their arrival at the rally, he handed the flag to Major Anderson. Major Anderson placed the flag in the hands of a statue of George Washington riding a horse, much to the delight of the approving crowd.

The War Department, represented by the Secretary of War, decreed that the flags of Fort Sumter, (a ceremonial flag & the war-torn flag) “could be in no better keeping than in the hands of the man who so gallantly defended them. They were thereupon placed in a strong box by Peter Hart, a humble hero in the story, and for years remained in the vaults of the Metropolitan bank.”

Major Anderson Reports to Washington D.C.:

In May of 1861, Major Anderson reported to Washington, D.C., where he was warmly received by the military commanders. The commanders expressed “their thanks for his gallant defense of the flag of the country, and fully approved of his conduct in the evacuation of the fort. They have already extended to him marks of their consideration and esteem, and will probably promote him in rank.”

The article also recounted Peter Hart’s gallant act in re-hoisting the flag and noted that he was “about to be presented with a beautiful gold watch, as ‘tribute to fidelity and courage’ by Major Anderson and his associate staff.” It was said that:

“The sovereignty of the Republic, symbolized in the flag, had not been yielded to the insurgents. That flag had been lowered, but not given up-dishonored, but not captured. It was borne away by the gallant commander, with a resolution to raise it again over the battered fortress, (Note: Italics added for later reference.) or be wrapped in it as his winding-sheet at the last.”

President Abraham Lincoln invited Major Anderson to the White House and praised him for his decision-making and actions. Major Anderson was then promoted by President Abraham Lincoln to the rank Brigadier-General, however, he never served actively in that rank due to failing health.

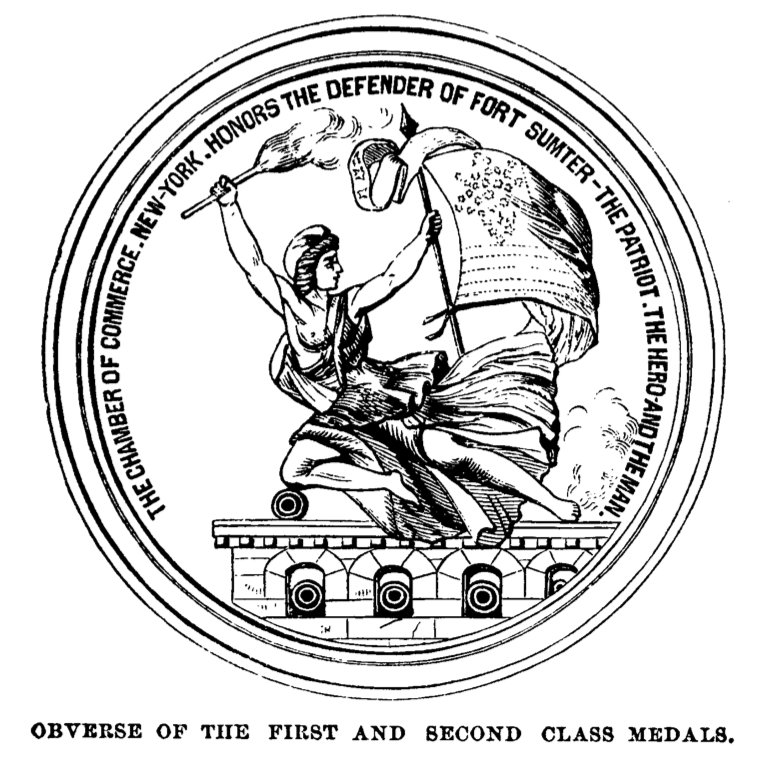

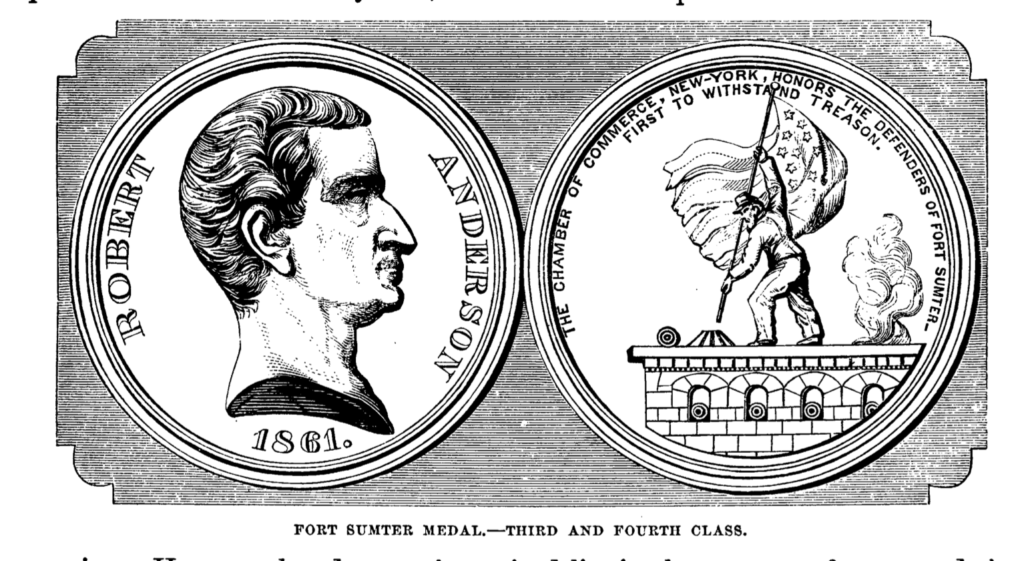

Medals Presented:

President Abraham Lincoln invited Major Anderson to the White House and praised him for his decision-making and actions. Major Anderson was then promoted by President Abraham Lincoln to the rank Brigadier-General, however, he never served actively in that rank due to failing health.

All of the men were presented with one of four classes of medals. The First Class Medal was a six inch table medal bearing an image of Anderson’s bust on the obverse, and the “Genius or Guardian Spirit of America rising from Fort Sumter, with the American flag in the left hand, and the flaming torch of war in the right.” This representation was designed to elicit patriotism for the defense of the flag.

To view the actual four original Fort Sumter Medals, that were auctioned by Cowan’s Auction House, on October 31, 2018, click here. (A new browser tab will open.)

The following text is taken from the minutes of the chamber of commerce, and was a footnote to a ballad written about the history of Fort Sumter.

The following remarks before Peter Hart received his medal:

“Peter Hart, an officer of the New York Police Force, accompanied Mrs. Anderson in her visit to her husband in Fort Sumter. When the barracks took fire, during the engagement, he exerted himself gallantly to extinguish the flames, while shot fell and shells were bursting around him: and when the flag was shot down, and the rebels’ fire was concentrated on the flag–staff to prevent a rehoisting of the colors, Hart nailed the flag upon the wall, under a storm of shot, and amid the cheers of our brave troops in the fort.”

Patrolman Peter Hart was introduced amid great applause by the following remarks of General Anderson, who held his hand.

“I am happy gentlemen of the chamber of commerce that you honor a man, who, though not a soldier, what is the greatest value to me at Fort Sumter. He was with me in Mexico and was a soldier under me there. At Fort Sumter, he was a confidential friend, and had a charge of our marketing and our mails.”

“He is the man who is represented on this picture as nailing the flag to the mast.”

Post-Civil War; A Promise Made & Kept:

When the war was over, Brigadier General Robert Anderson held true to the words he spoke in Washington, D.C. in May 1861; that at some point in the future, he would raise the 33-star flag once “again over the battered fortress.”

A newspaper report, dated September 18, 1861, indicated that First Lieutenant Peter Hart of Fort Sumter was enlisted in an artillery company of 150 men, mostly Germans. The commander of the company appears to have been Curran Pope, of Buffalo, a graduate of West Point.

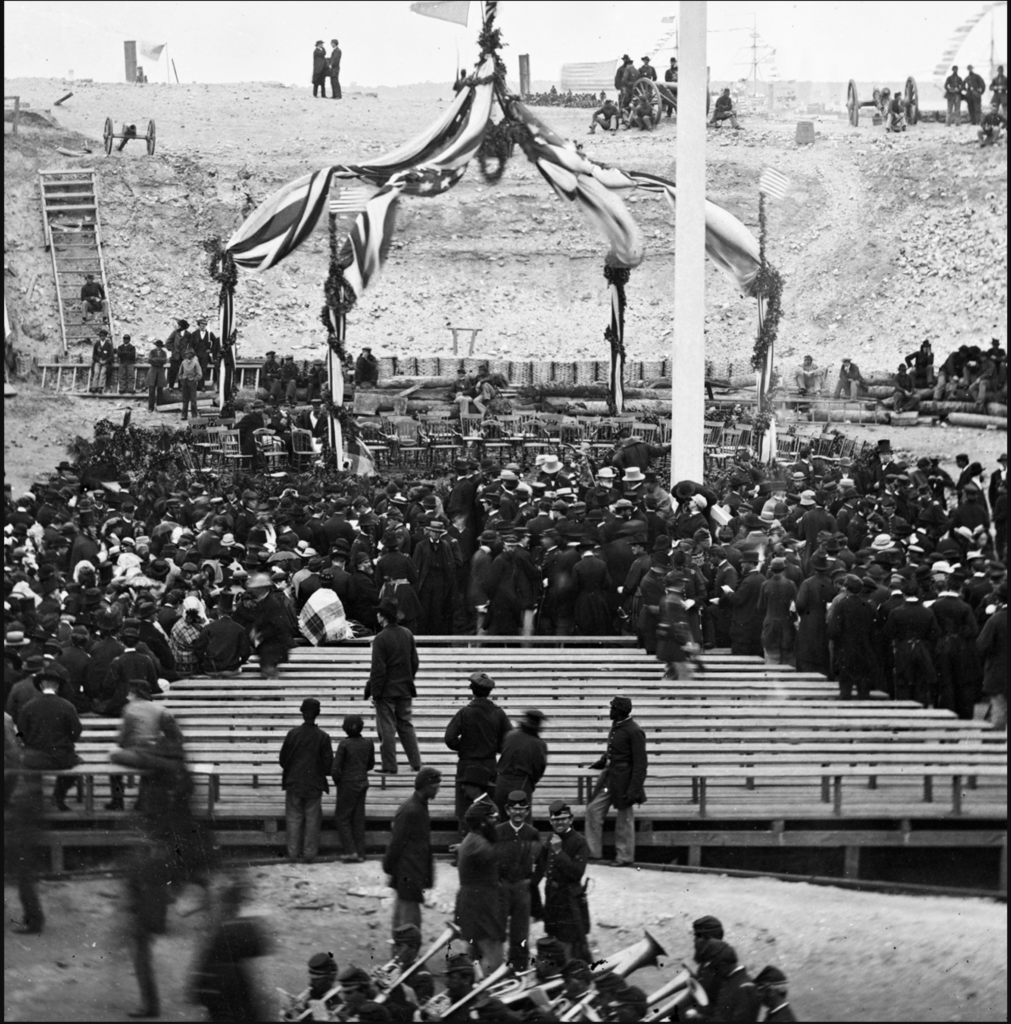

On April 9, 1865, the government transport ship Arago, a large paddled wheel steamer, sailed from its berth on Beech Street, NYC, for a journey to Fort Sumter. A U.S. Mail Bag, dated to April 1861 and the 33-star flag, in the possession of Peter Hart, along with sixty-one passengers departed at 10:00 am.

In addition to Genl. Anderson’s speech, a prayer was offered by Chaplain Matthias Harris, who was at the Fort during the 1861 conflict. Additionally, Henry Ward Beecher, a famous Reverend from Brooklyn, and an abolitionist, delivered an oration. To Read The new York Times article on the event, click here (A new browser window will open.)

The ceremony was held on April 14, 1865, and the 33-star flag was handed by Peter Hart to General Anderson, who raised the flag. “There was prayer, a brief address, and the singing of patriotic songs.” One hundred guns were fired to close the ceremony.

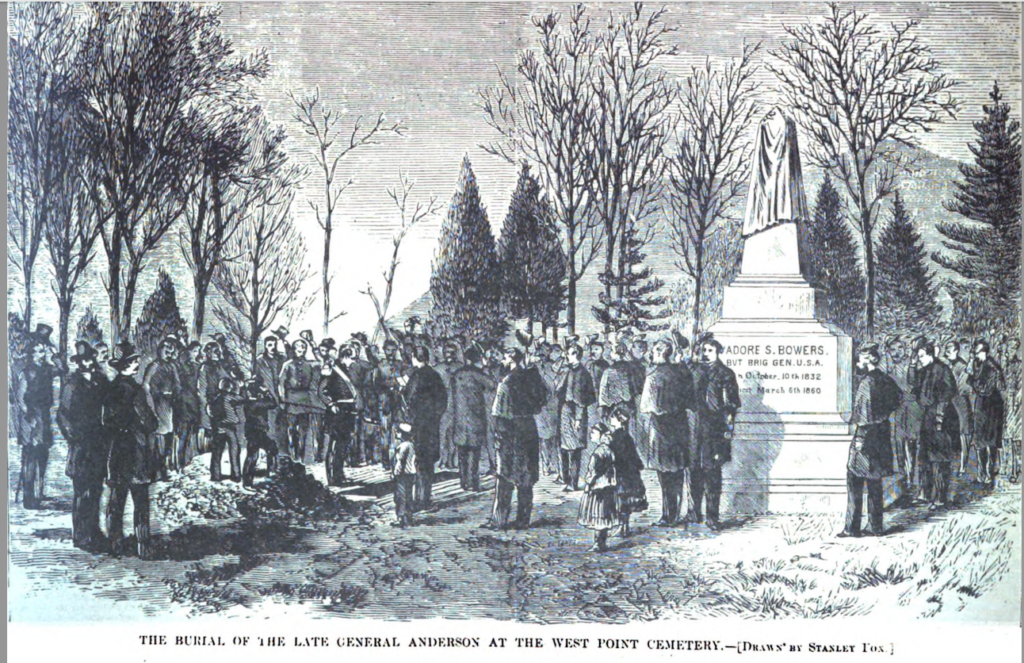

Brigadier General Robert Anderson’s Death & Unremarkable Burial:

Brigadier General Anderson died at the age of sixty-six, on October 26, 1871, in Nice, France. According to an obituary printed in a newspaper, Anderson graduated West Point in the class of 1825.

Upon the arrival of the General’s casket in NYC, the casket was placed on an artillery carriage and draped with the flag of the battle of Fort Sumter. The casket, flanked by members of the Old Guard, was escorted from the Marble Cemetery on 2nd Street, to a steamer located at the foot of 34th Street. The procession was composed of police, military, and civilian units and organizations, many of which boarded the steamer to the burial site at West Point.

Upon the arrival of the large funeral party at West Point “it became evident that West Point did not propose to show any honors to the remains of the gallant dead.” There were no troops in formation, no salute fired, and no music played. “Not a man raised his hat.” A chaplain from Brooklyn read passages from The Bible, as dirt was piled upon the coffin.

A reporter from The Sun, approached a General Ruger, Commandant of West Point, and inquired as to why there was a lack of etiquette for General Anderson. Ruger replied “We had special orders from the War Department to pay no funeral honors to General Anderson here.”

Note: The author continues to research and investigate the reason(s) behind the aforementioned “special orders” and will update this article at the appropriate time.

Peter Hart’s NYC Police Career, the Chain of Custody of the 33-star Flag, and his Death:

Peter Hart was appointed as a Patrolman on January 21,1860, during the term of New York City (NYC) Mayor Fernando Wood (1855-57 & 1860-1861). Patrolman Hart was assigned to the Twentieth Precinct Station-house, located at 212 West Thirty-fifth Street, under the command of Captain David McKelvey.”

After returning to NYC, he “resumed his duties as a policeman” and “obtained a good position in the city hall and remained on duty there till his retirement upon a pension of $600 per annum in 1887.”

On Friday, September 13, 1878, military Captain Peter Hart, was one of many veterans of the Mexican-American War that commemorated, and celebrated, the thirty-first anniversary of the capture of Mexico City.

The flag, for whose honor he risked his life, is preserved in the Bank of Commerce in that city.” (New York)

In May, 1884, Patrolman Hart, Twenty-sixth Precinct, was ordered to be examined by the police department’s Board of Surgeons to determine if he was fit to continue duty as a police officer. It was resolved by the City Council that Hart be granted full-pay during the process.

Patrolman Peter Hart was granted retirement on June 24, 1887, having served twenty-seven years and five months, with an annual pension of $600.00. He was last assigned to the Third Precinct (City Hall). After his retirement, Hart resided at 856 Bedford Avenue, Brooklyn, with his wife, eight sons and two daughters!

(Note: Since this article was first published, the author was contacted In April 2023 by a 3rd Great-grandson of Perter Hart, who himself is a retired Colonel of the U.S. Air Force.)

According to a newspaper that carried his obituary, the “Hero of Fort Sumter was not a soldier, but a New York Policeman,” and died, at the age of sixty-eight, in Brooklyn on/about February 20, 1893 (incorrect date). According to the obituary, Hart volunteered, for military service in the Mexican-American War and took part in every battle of the war. After the war, Hart was awarded the “Faithful Service” medal.

According to his Official NYC Death Index Record, Peter Hart was born in about 1824, in Germany. He died from “Cerebral Apoplexy” on December 13, 1892, and was buried in Evergreens Cemetery. Hart’s mother was Born in Germany, and his father in Ireland.

According to an 1898 chronicle, the 33-star flag was in the possession of Mrs. Anderson, then residing in Washington, D.C., and stored in a safe deposit company when not in her care. The flag was described as being ten feet wide by fifteen feet long, and made of a “coarse mesh” threading. A second flag, known as the “garrison flag,” was made of finer material and flown only in excellent weather and for ceremonial purposes. The 33-star flag is presently displayed at the Fort Sumter Museum.

A poem was written about Peter Hart’s actions. Click here to view it. (Note: A new browser window will open).

From John Paul Jones during the Revolutionary War to the 1969 Moon Landing; Peter Hart’s Act of Valor & the Connection to the National Anthem:

Initial (2022) and subsequent (2023) research findings support the author’s belief that if not for the presence of Peter Hart at Fort Sumter at the outbreak of the Civil War, and his act of valor in preserving the flag above the nearly destroyed fort, it is unlikely that the “Star Spangled Banner” would be the National Anthem of the United States of America.

The premise that the actions of Peter Hart at Fort Sumter gave rise in popularity to the song, the “Star-spangled Banner” was not conceived by the author during his reseach, but rather were discovered during research from a variety of sources.

According to the Americn Landmarks Commission, “The song’s profile rose immensely during the Civil War, when some made comparisons between the situations at Fort McHenry and Fort Sumter.” According to The National Park Service, the song “went with the Union armies as they entered New orleans, Savannaj, Richmond and many other towns in the defeated South.” The U.S. Captiol Visitor’s Center declares that the song “gained favor as a patriotic song. It was one of the most popular Union songs of the Civil Wat, and in the 1890s the U.S. Navy and Army adopted it for flag ceremonies.”

In an article, entitled “Deeds of Heroic Americans in Defense of ‘Old Glory’” printed in July 1917 in the periodical “Gas Logic,” several similar acts of bravery and valor surrounding the flag are recounted. The article provides short details on: 1) Captain John Paul Jones, who in 1779 “is said to have been the first to hoist our flag aboard an American man-of war” (Battleship) and proclaimed “I have not begun to fight!” 2) Revolutionary War Sergeant William Jasper of South Carolina, who on June 27, 1776, at Ft. Moultrie, re-raised the flag-staff while under fire. Sgt. Jasper lost his life three years later while performing a similar act during the attack on Savannah by the British. 3) The raising of the Star-spangled Banner on the heights of Chapultec by Captain Barnard of Philadelphia.” Capt. Barnard, on September 13, 1847, near the end of the Mexican War, took the flag from a fallen flag bearer and scaled a high wall to unfurl the flag in defiance of the enemy. 4) The act of Peter Hart on April 13, 1861 at Ft. Sumter. 5) One of many notable acts during Civil War were alluded to. In one paricular event at Chancellorsville, the color-bearer of the 37th New York Infantry wrapped the flag around his body to protect it from being torn in thorny brush. The bearer was killed and unknowingly buried with the flag which was secreted under his clothing.

A 1983 periodical “Civil War Times Illustrated” added to the above list 6) The planting of the U.S. Flag during World War II on Iwo Jima and 7) the plating of the U.S. Flag in 1969 on the Moon by U.S. Astronauts.

The National Park Service contributed this: “Fun Fact: Francis Scotty Key’s grandson was at Fort Sumter during the Civil War!”

To ascribe data to the rise of the National Anthem, the author performed a search of the newspaper archival site www.newspapers.com using the search term “star spangled banner.” The following data and charts, in my opinion, support the premise that, if not for the act of valor of Peter Hart, the Star-spangled Banner Songwould not be today’s National Anthem

On the 150th anniversary of the actions of Patrolman Peter Hart at Fort Sumter, his name and heroic act was placed into the public record. New York Representative Steven Israel, spoke the following words on the floor of the U.S. Congress, which were officially entered in to Congressional Record on April 13, 2011.

Of the few research findings, the best stems from a search of the newspaper archival site www.newspapers.com using the search term “star spangled banner.” The following data and charts, in my opinion, support my position.

On the 150th anniversary of the actions of Patrolman Peter Hart at Fort Sumter, his name and heroic act was placed into the public record. New York Representative Steven Israel, spoke the following words on the floor of the U.S. Congress, which were officially entered in to Congressional Record on April 13, 2011.

Conclusion:

Patrolman Peter Hart is one of the thousands of NYC police officers who served the country in the military. However, his service to the country stands out as exceptional as a result of circumstance and his display of patriotism, gallantry, valor, and heroism. His act of rehoisting the flag, which symbolized the “sovereignty of the Republic” set the tone for the Union’s fervor for preserving the United States.

Research disclosed that Patrolman Hart was declared “New York State’s first volunteer,” “The hero of Fort Sumter,” and a “National hero.” The facts that he was granted a leave of absence by the police department and left his wife and six children to escort Mrs. Eba Anderson on a perilous journey as war was imminent, is a testament to his character and loyalty. The fact that the War Department entrusted the Fort Sumter Flag to his custody and care speaks volumes.

Research findings support my belief that if not for the presence of Peter Hart at Fort Sumter at the outbreak of the Civil War, and his heroic act preserving the flag above the nearly destroyed fort, it is unlikely that the “Star Spangled Banner” would be the National Anthem of the United States of America.

Why has Peter Hart’s name, and his history-changing act, largely fallen from discourse? The Police Department of the City of New York and the City and State of New York should recognize Peter Hart in some suitable form of recognition. Sharing his story can only serve to inspire others.

Further Reading & Peter Hart’s Artifacts:

View historical items from Fort Sumter, that once belonged to Peter Hart, and were auctioned by Cowan’s Auction House, on October 31, 2018, click here. (Note: A new browser tab will open.)

To learn more about the Fort Sumter National Monument Visit here: (Note: A new tab will open in your.)

The ballad; “Peter Hart,” by Edward S. Rand, Jr., 1864 (Click here, a new tab will open in your browser.)

The ballad; “A Ballad of the Siege of Sumter; The Banner of Stars,” by Augustine E.H. Duganne, (Click here, a new tab will open in your browser.)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.