![]()

Introduction

Methods of communicating over any distance remained unchanged for several millennia. The choices over the years were limited and ranged from: pictographs on cave walls, verbal communication, human runners carrying messages, humans riding animals armed with messages, fire/smoke signals, signal flags, wooden rattles, whistles, rapping nightsticks on curbs, etc. What invention sparked the greatest change? Electricity.

The advent of the electric telegraph, circa 1837, enabled communications to enter a new era, expanding exponentially in the 150 years that followed. The advancements in that period permitted humans to communicate instantly worldwide and to space. The electronic computer chip, which replaced transistor and tube technology, marked the second major advancement to effect communications.

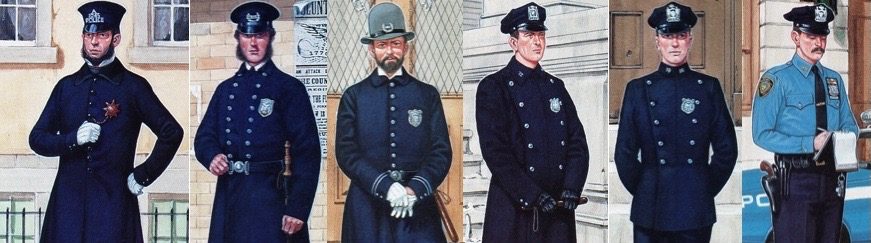

The modern style of policing is attributed to Sir Robert Peel who, in 1828, convinced the British Parliament to enact legislation creating the world’s first professional police force. Soon after, cities in the United States of America followed, and in 1845, the City of New York which, created its first well organized police force. The need for police to communicate would not necessarily drive the innovations and inventions. Police leaders historically have, with few exceptions, been resistant to change as is the case with some police leaders today.

The Era of the Telegraph (Data) Line

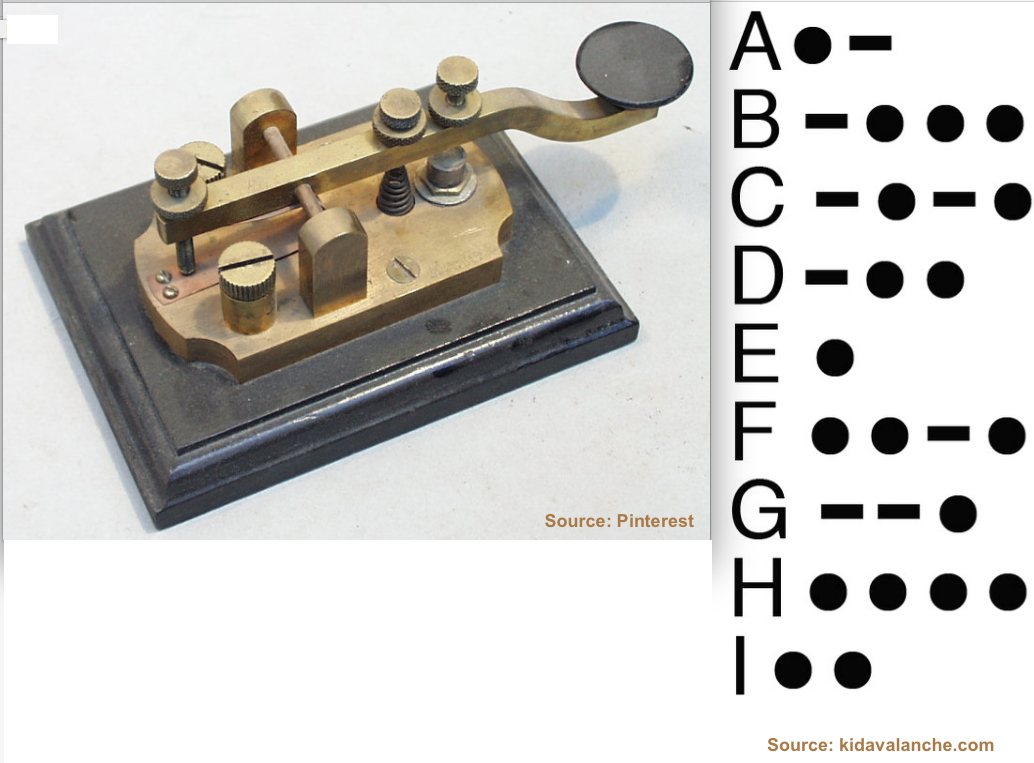

From 1846 to 1850, New York City (NYC) tested the Telegraph, utilizing “Morse Code,” for transmitting fire alarms, but it was not adopted widely. Morse Code, developed in 1835 by Samuel Morse and his partner Alfred Vail, consisted of a battery-powered system whereby each letter of the alphabet was represented by a series of “dots” and “dashes.” The dots and dashes were generated by the sender tapping of a “key” (which closed a circuit) and caused a signal to be transmitted over the lines. A dot was created by the sender keying a short tap, and a dash by a slightly longer tap. The recipients decoded the dots and dashes to the alphabetic letters they represented to create words.

In April 1857, the Commissioner of Repairs for NYC provided an estimate of extending the police telegraph to the existing Bell Towers (also referred to as Watch Towers) and police station-houses. Bell Towers existed throughout NYC, the City of Brooklyn, and elsewhere. Bell Ringers, employed initially by the police department and later by the fire department, were posted in the towers to watch for fires and rang the bell to sound an alarm.

In September 1857, Charles C. Robinson, credited with inventing the “Police Telegraph,” had been hired as Superintendent (Supt.) of all business for the newly instituted Metropolitan Police District. The District, created by an Act of New York State Legislature, and ratified by the localities effected, encompassed the police departments in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Richmond and the lower part of Westchester County (known today as the Bronx).

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper that reported that Supt. Mason made some improvements to the telegraph system in NYC; that he had added a “Dial System” to the telegraph; that the same improvements would soon be implemented in Brooklyn; and that the systems in the City of Brooklyn and New York would soon be connected by a submarine cable under the East River. The submarine cable was completed in July 1859 at “Hells Gate” on the East River. According to one source, almost $15,000 was expended during 1857 on “Police and Fire” telegraphs.

In 1858, NYC contracted with a firm to construct a telegraph system for their Police Department (PD). This system was used by the PD during the Draft Riots of 1863. The riots were ignited by the federal government’s institution of a draft in the city in order to enlist men to fight in the Union Army during the Civil War. The riots lasted four days, and were generally confined to Manhattan Island, although there were some incidents in the area of lower Westchester County (now the Borough of the Bronx).

The riots caused widespread mayhem and involved heinous crimes such as assaults, murders (including lynchings), arson and looting. Hundreds of police officers were severely assaulted and four died as a result of their injuries. The members of the PD’s Telegraph Bureau were credited for risking their lives to restore telegraph lines that were torn down by the rioters and for quickly, and accurately, relating information during the insurrection. The Draft Riots were the first large-scale event that confronted the PD and, as a result of dozens of individual and overall acts of heroism, as well as the professionalism displayed by the PD, became a source of pride for the members and the citizenry.

The system grew from one where telegraph stations were used only at Police Headquarters, (located at 300 Mulberry Street) and in selected precinct station-houses, to one where individual officers, and selected, trusted citizens were added to the system. As a result, the method of communication (Morse Code) needed to be simplified or replaced. As briefly mentioned above, in 1858, the firm of “Charles T. & J. N. Chester” developed a “Dial Telegraph” for NYC. The Dial System operated by the movement of a key from one location on a dial to another. Each location on the dial represented an alpha-numeric character. The placement of the key on the letter would cause that alphabetic letter to be sent over the line.

While many departments adopted the use of the telegraph, the widespread use of the telegraph by police departments was inhibited by the perception of politicians, and citizens, that there was no need for a costly, complex system of communication to aid law enforcement.

Prior to the ability of NYC foot patrolmen to receive information from either headquarters or their precinct, a citizen requiring immediate help needed to find the beat officer, or appear in person at a local precinct to report a crime or call for assistance. Likewise, officers on a beat relied on the rapping of their hardwood nightsticks against a curb, or blowing their cylindrical-style police whistles to summon aid from officers on adjoining posts. Police commanders needed to have their messages and orders communicated by hand delivery to all local precincts. The delays in communication resulted in loss of life and property, decreased efficiency in administration and inability to contact patrolmen. The benefits derived by the fire services use of the telegraph served as one of the justifications for the PD to adopt the system.

The Metropolitan District would be abolished in 1870 and the City of Brooklyn once again had its own Police Department (BPD). In July 1876, telegraph communication in Brooklyn was possible between the PD, the penitentiary, ambulance services, all public buildings, and other cities, including NYC.

In January 1884, BPD Supt. of Telegraph George Flanley retired and his successor would need to take a competitive civil service examination to be considered for the position. Mr. Frank C. Mason would be appointed, in March, as Flanley’s successor.

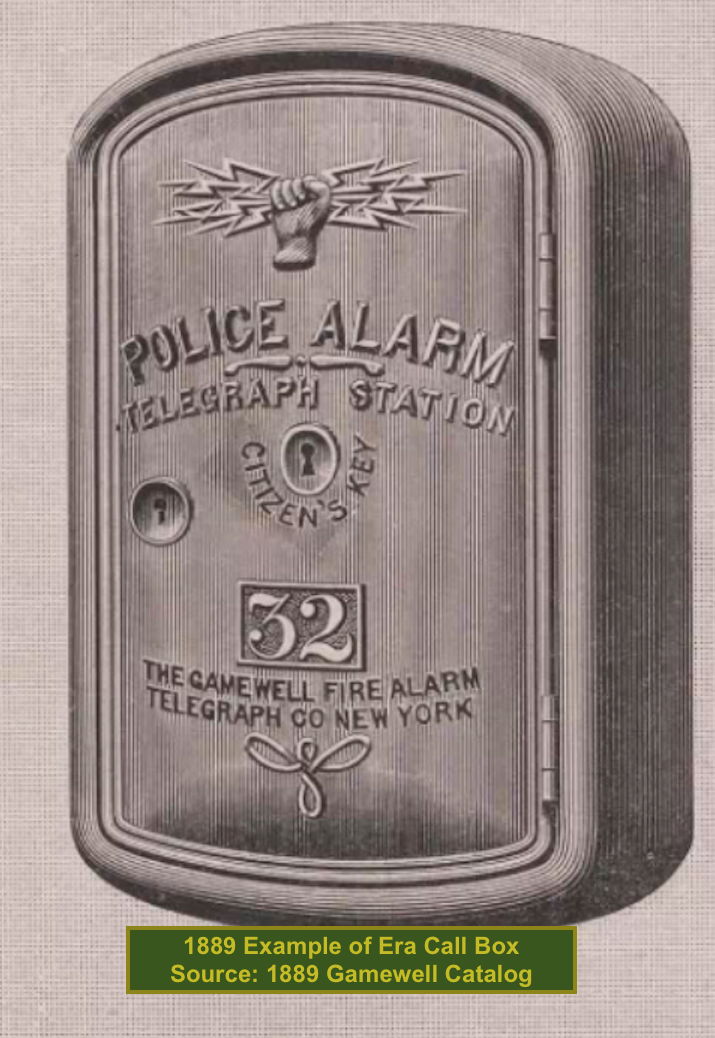

Telegraph Boxes

In February 1884, Supt. Mason was credited with many improvements which were first used by BPD, including the use of small iron boxes as opposed to the unsightly booths used elsewhere like in Chicago where large iron booths were used.

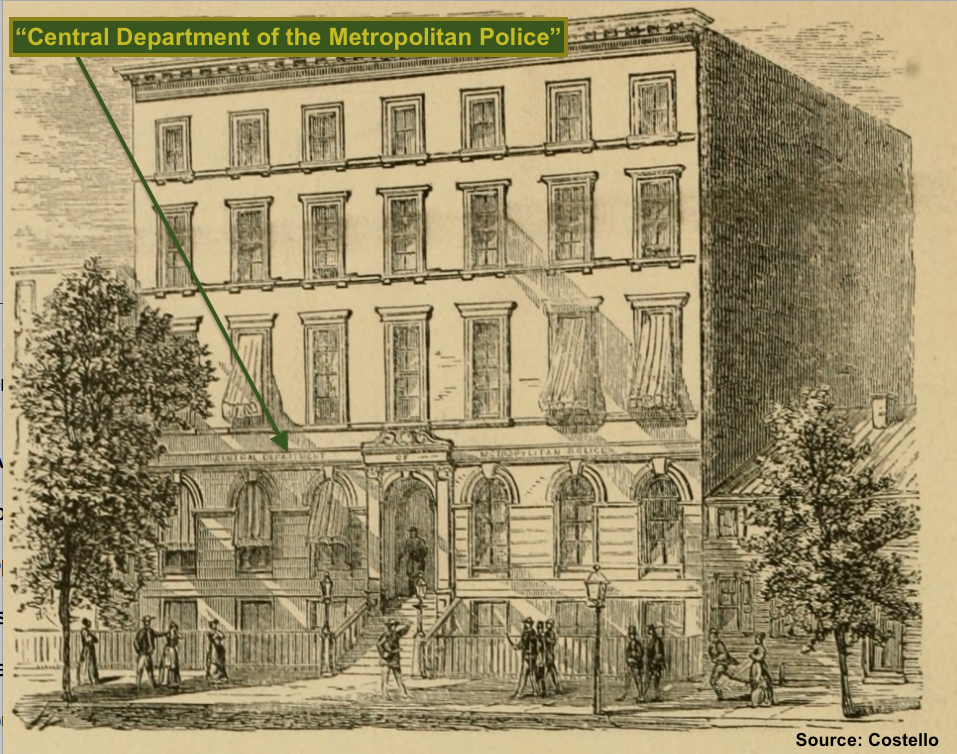

In 1884, the NYC PD utilized telegraph boxes in their outer districts, where the population was less dense and the area of responsibility of each Patrolman was greater than in the congested parts of lower Manhattan. Author Augustine Costello, in his 1885 book entitled “Our Police Protectors. History of the New York Police from the Earliest Period to the Present Time,” described one rural precinct, the Thirty-second, as follows: “This is a mounted police precinct and even the horsemen are aided by boxes from which they can send necessary signals to the station house.” Costello wrote that the Supt. of the Telegraph Bureau was James Crowley and that the Bureau operated out of the basement of the Central Office (Headquarters) located at 300 Mulberry Street.

The Annual Report for the Police Department of the City of New York (ARPDNY) for 1885 indicated that the telegraph lines were divided into five sections covering the city and that by turning a switch, “general alarms” were transmitted to all five divisions simultaneously. The report further indicated that several other entities were connected to the Central Office, including: Fire Department (NYC) Headquarters, Brooklyn Police Headquarters, Yonkers Police Headquarters, hospitals, railroad offices, and burglar alarm companies. A total of 105,070 messages were transmitted during 1886.

BPD’s Headquarters was connected with twenty of their thirty precincts, and utilized 569 miles of wire. There were 355 patrol call boxes for use by citizens and officers, and seventy-one telephones. Prior to the placement of the call boxes, the supervision of foot patrolmen, in both NYC and Brooklyn, relied on contact with the Roundsman (the equivalent to today’s rank of Sergeant.) Once the call boxes were installed, patrolmen were required to: make hourly contact with their precincts using the call boxes; use them to call for aid, an ambulance, to report arrests; and call for a Patrol Wagon to take custody of prisoners.

The advantages of the telegraph were obvious, and the timing of the next invention and innovation resulted in a more efficient and faster means of communication for the police and citizens that they served.

The Telephone (Voice) Line

Concurrent with the use of telephones in both cities, in 1877, Brooklyn PD’s Supt. of Telegraph Flanley was experimenting the use of a telephone installed in headquarters and, according to an article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, “his object being to utilize it in some way for the benefit of the force, the ordinary telegraphic means of communication having already been brought to the highest perfection under his supervision.” In 1880, two precincts of the NYC PD were listed in a NYC public telephone directory, but by 1882 they were no longer listed. It is not known if the phones were disconnected or simply unlisted. As mentioned, in 1885, the BPD used a number of telephones to supplement telegraphic communications. The NYC PD lagged behind and, according to an editorial that appeared in the New York Tribune on July 20, 1886, the paper admonished NYC officials for the delay, writing “this wonderful invention has been used for six years to connect the police central office in Brooklyn with the police stations…and its advantages have been found too great to enumerate. If they (the NYC police) wish to keep up with the times, they will put in telephones without delay.”

In 1886, Inspector Thomas Byrnes, of the NYC PD’s Detective Bureau, established his office on Wall Street, Manhattan, in the building of the New York Stock Exchange. The Exchange was connected by telephone with every bank and financial institution in NYC. Inspector Byrnes capitalized on the exchange’s telephone system to dispatch officers to any bank in the city that reported a robbery, which resulted in an increase in arrests and decrease in robberies.

In 1887, the NYC PD had telephone line connections between Headquarters, the PD’s Telegraph Bureau, and with the public telephone system. The simultaneous use of hybrid telephone and telegraph systems increased the efficiency of communications. Following the lead and proven success of the Chicago PD, where the system had been in use since 1880, the City of Brooklyn adopted the hybrid system in February of 1884. The efficiency and productivity demonstrated by the use of the hybrid system over the telegraph, made it evident that the telephone was a superior means of communication and as the public telephone exchanges grew in number, and spread geographically, so followed the NYC PD’s use of the telephone.

On April 22, 1886, rules relating to the use of signal boxes were adopted by the NYC PD. The instructions were that the officer pull down the crank and signal the code, then release the crank. A Desk Officer at the precinct inspected a tape (like a “ticker” tape) that contained markings and make note of the communication in a book called a “blotter.” When a Desk Officer wanted to signal a Patrolman, he signaled the box number that the Patrolman was to use by causing a series of taps on the bells of the signal boxes, for example “2-3” for box twenty-three. Sergeants were responsible for inspecting boxes for damage or tampering.

By 1890, the Dial Telegraph system, in use for thirty years, was reported to be in need of a general overhaul. The NYC Board of Police Commissioners expressed that the PD was overdue for the implementation of an “Electric Signal System” and that any expenditure to purchase and install the same would be supported by the taxpayers.

The Columbian Exposition of 1892, held in Chicago, displayed the latest telephone system and other technologies. The demonstration of the latest in telephone technology led to the adoption, in 1893, of a modern telephone switchboard and system by the NYC PD.

In 1898, the City of Brooklyn, various towns and villages in Brooklyn, Queens, Richmond County, and the area of today’s Bronx County were consolidated into the Greater City of New York under one police department, the Police Department of the City of New York (PDNY). After the consolidation, communications would expand greatly in the outer boroughs of the Bronx and Queens and a total of 119,451 messages were sent via the Signal Box system alone. Manhattan had not yet been equipped with a telephonic Signal Box system.

By 1903, ten years after the Columbia Expedition, the New York Telephone Company had installed a total of 661 telephones in Manhattan’s twenty-nine police precincts and the decision was made to replace all telegraph apparatus with telephones. According to the ARPDNY for 1905, the conversion would be completed that year in Manhattan. The report indicated that the system was extended to the outer extents of the rural Borough of the Bronx in September 1905.

By 1908, the PDNY had addressed their use of telegraphs and telephones in great detail. The 1908 Rules and Regulations for the PDNY indicate that the “Bureau of Electrical Services” consisted of the Supt. of Electrical Service and the Supt. of Telegraph. What followed was twenty-eight paragraphs describing in great detail when, how, by whom, etc. the telegraph and telephone equipment may be used, and how such use was to be documented in writing. The next section details the chain of command, and procedures, for transmitting from Headquarters to precincts, General Alarms and Orders. Two additional sections similarly address scenes of major fires and “Unusual Occurrences, Disasters, etc.”

Beginning in 1892, above ground (aerial) telephone and telegraph lines were removed and put underground or in subway tunnels, with 386 miles of these underground wires in use by 1896.

Concurrent with the use of the Telegraph was the use of another means of communication, called the “Police Signal” or “Call” Box.

“Police Signal Boxes” Also Known As “Police Call Boxes”

Voice telephones used by the NYC PD took on a few different forms which were used simultaneously by the NYC PD. “Police Signal Boxes,” also referred to as “Police Call Boxes” appeared, beginning in 1892, throughout the city at the same time as the Flash Light/Recall System detailed in the following section.

These Signal Boxes were mounted to buildings, or posts, and were wired to station houses via telephone lines. The need for patrolmen to walk to a precinct to report minor occurrences on post was abolished and replaced with a regulation requiring communication of the same via the Signal/Call Box. Additionally, each Patrolman was required to call in hourly (called a “ring”). If a Patrolman’s ring was late by fifteen minutes, a Roundsman would be sent out to locate the Patrolman, and to determine the cause for his delay. Disciplinary action could result from a delayed ring(s). Likewise, officers were expected to answer calls made to the boxes by listening for the ringing of a bell in a Signal/Call Box. This was not practical, however and if officers were expected to respond to the telephone box to answer a call, a different method of signaling needed to be invented.

In 1894, electricity came to the police department when an electric elevator was installed in the Central office and the police boat steamer named “Patrol,” was converted with an electrical plant, permitting incandescent lights and a searchlight to be installed. In 1896, renovations were underway in the Central Office and incandescent lights were installed in the office of the Chief of Police.

In the ARPDNY for 1908, the Signal Box System in Brooklyn was described as “utterly inadequate and practically out of commission” and the underground lines were in need of replacement. Citing “technical and practical improvements” in the technology of the telephone, it was said that monies be directed to further advance their use.

Interestingly, it was noted in the ARPDNY for 1918, that in the event of a large fire on his post, a Patrolman was required to communicate the same via a Call Box to the precinct, which would then pass the message along to Headquarters. Headquarters then dispatched “Operators” and “Linemen” from the Bureau of Telegraph to the scene to install a “general telephone service” line which would permit calls made to any other telephone. (Note: For more information on the use of a general telephone at the scenes of fires, read the article on this blog site entitled “What’s the Deal:” With The First Use of the Command Post Flag & Lanterns Used by the NYPD in the Last Century?”)

The 1918 Annual Report indicated that 1,541,404 telephone connections (calls) were logged and 398,234 messages were recorded (documented). Additionally, the Bureau of Telegraph demonstrated the ability to set-up wired field telephones for use at large gatherings or scenes. These wired field phone permitted communications between commanding officers on scene who were separated by distance.

The Use of the Police Recall or Flash Light System

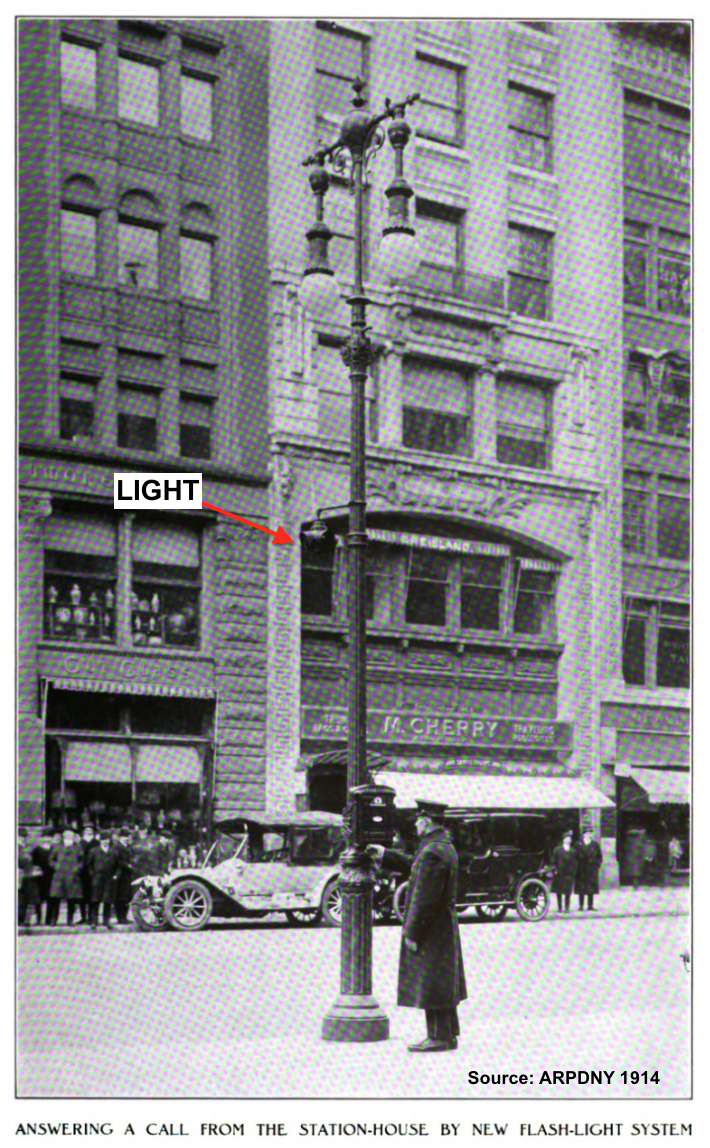

Following the success by other departments, in 1914, the PDNY experimented with a flash light recall system in its Twenty-third Precinct (West 50th St. Station-house). The precinct was divided into zones and lights were installed on poles above each patrol Call Box. When the precinct wanted to get the attention of a Patrolman walking his beat, they would turn on a switch for the zone and the light would flash, and a bell would ring, every four seconds.

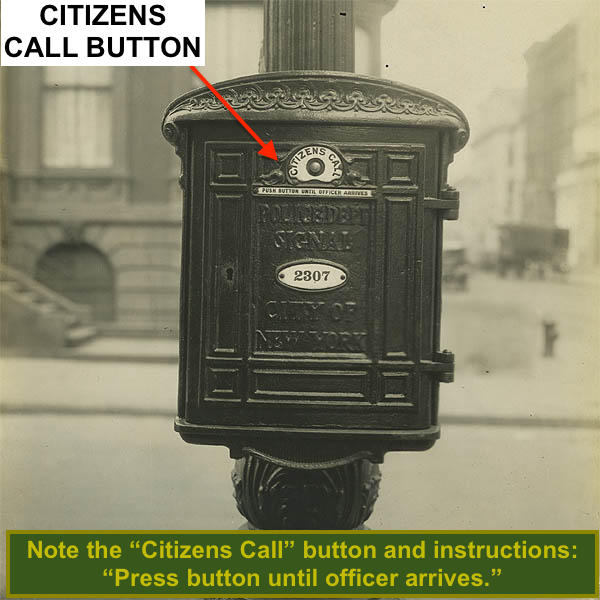

Adding an innovation not used elsewhere, the PD added a button to each box whereby a citizen (or teenage prankster) could push the “Citizens Call Button” which caused the light to remain lit steadily until the arrival of a Patrolman. According to the ARPDNYs for the period, the system was so effective and efficient that by 1915 six additional precincts adopted the system and plans to extend it to an additional sixteen precincts were made. The ARPDNY for 1918 noted that it would be “considered neglect of duty for any member of the force to let it flash for any considerable length of time without responding; or, should a member of the force be notified by a citizen that the lamp had been flashing and was not answered, it is his duty to call up the station-house and give his rank and name.”

Citizens often were the first to see the flashing light and notified the Patrolman who hurried to the nearest call box to find a large group of people gathered to see what was going on. In any event, the system worked, was extended as planned, and in 1919 precincts in Brooklyn were added. By 1921, there were 1,313 Signal Boxes installed in all five boroughs, 203 of which were Flash Light System Boxes. The Flash Light Recall System was effective, however, advances in other inventions were on the horizon and would soon be adopted by the PD.

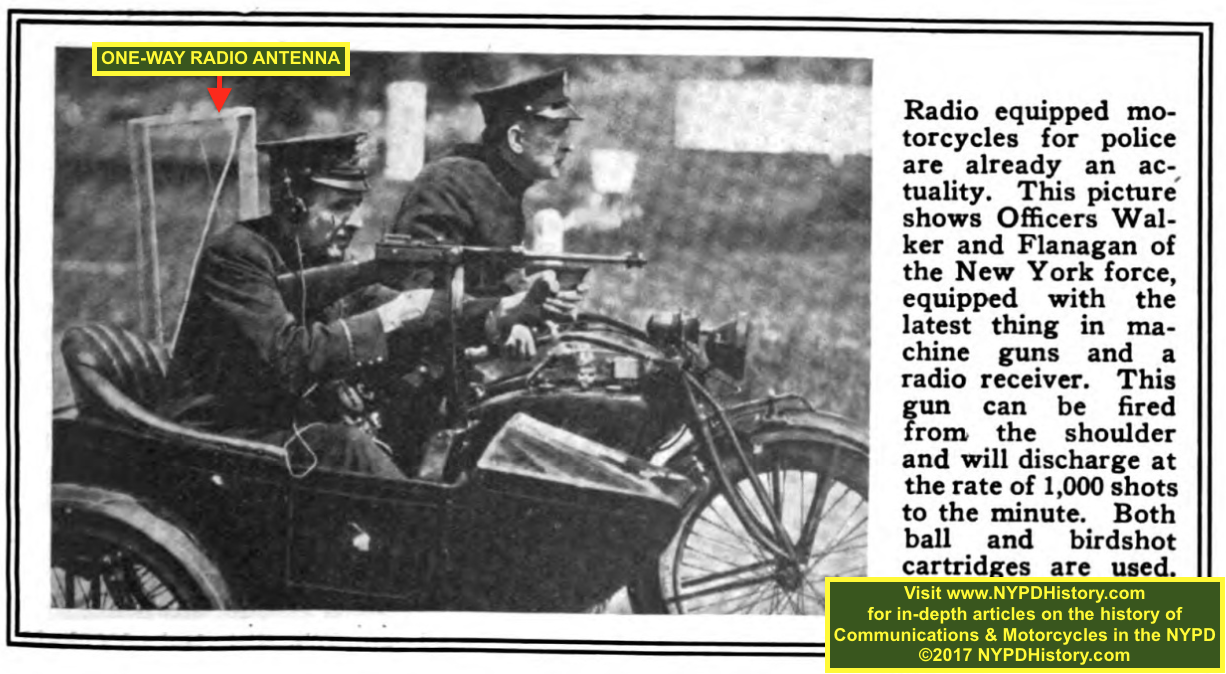

Mechanization and Motorization Combined With Wireless Telegraphy (Data/Voice)

The invention and adoption of mechanized and motorized vehicles by the PDNY permitted an officer to cover a greater area than that of a Patrolman walking a beat and enabled the police to keep up with the civilians’ use of motorized vehicles. The horse, bicycle, motorcycle, and automobile were utilized by the PDNY to patrol/cover larger areas, enforce laws, and as a method (vehicle) for communicating messages and documents throughout the city.

The Mounted (Horse) Squad was formed in 1871, the Bicycle Squad in 1896, and the first automobile and motorcycles were purchased by the PD in 1905. Other than in the rural districts of NYC, where Patrolmen utilized horses, bicycles, and motorcycles to patrol beats, Patrolmen in the congested areas remained on foot and were supplemented by other officers using their mounts and vehicles for special enforcement such as traffic laws.

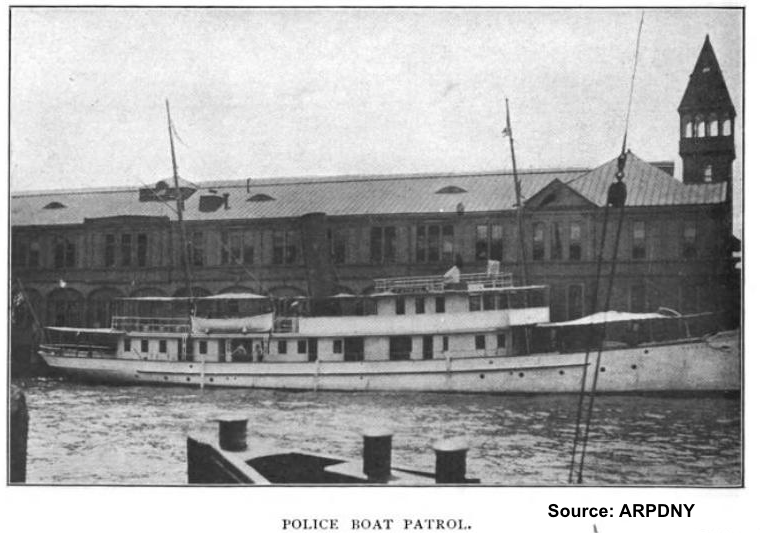

For decades NYC had a Harbor Police Squad and a Steamboat Squad that operated simultaneously. The Harbor Squad patrolled the waterways around NYC. The Steamboat Squad had boats, but focused more on the people and cargo that reached one of the city’s hundreds of docks and wharves.

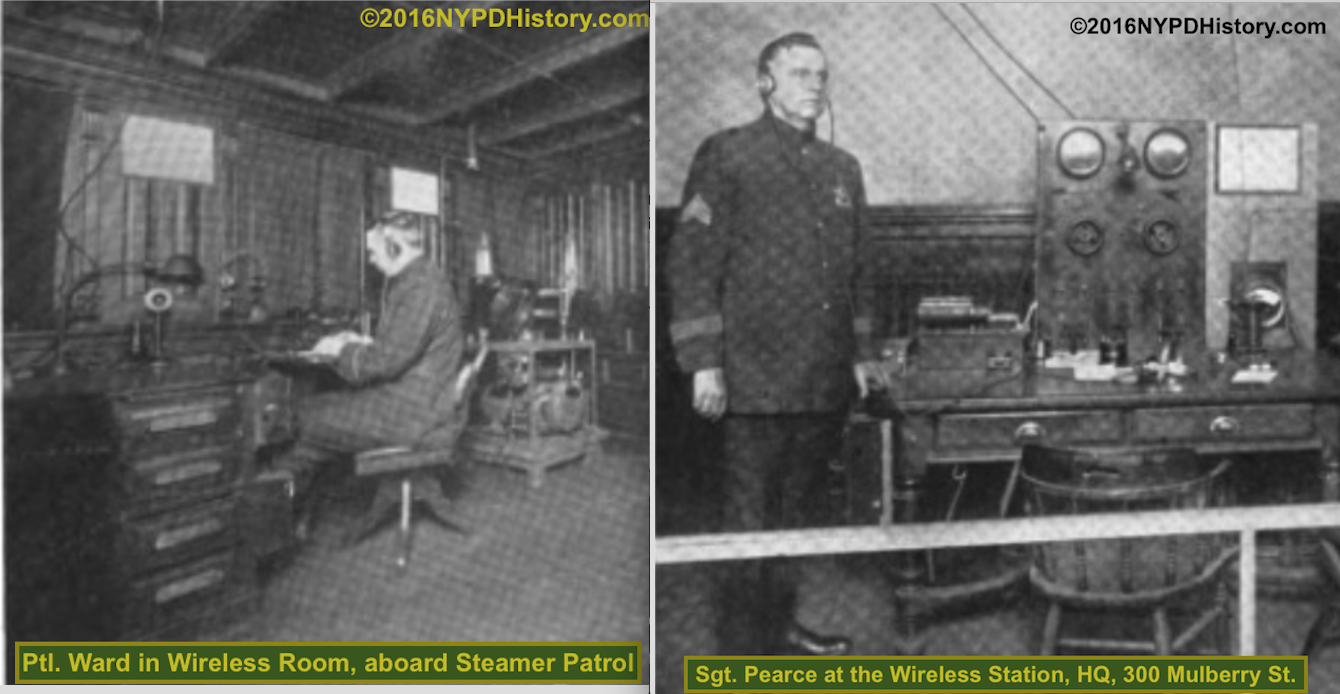

In 1908, it would be the Harbor Squad’s “Patrol” that would be the first motorized vehicle to be equipped with wireless telegraphy, enabling Morse Code communication between the soon to be occupied Headquarters building, located at 240 Centre Street, and the steamer. The cost of the system was $2,500. It would not be until after the end of the Great War (World War I) in 1918 that further advances in wireless telegraphy (referred to in the period as “radio”) would be used by the PDNY.

The earliest mention of the word “radio” appears in the ARPDNY for 1918 in connection with the wireless telegraph/radio communications between Headquarters, “Patrol” and the United States Navy Yard, in Brooklyn. It must be remembered that NYC’s ports were bustling during the war effort, and troop ships were leaving and arriving daily.

In 1917, Chief Inspector Max F. Schmittberger (today’s rank of Chief of Department), under the administration of Police Commissioner (PC) Arthur H. Woods, ordered that a radio be installed in a truck and that the truck be displayed at the annual parade of the PDNY. The truck enabled communication with one motorized vehicle, the steamer “Patrol,” as well with Headquarters. Traveling south on Fifth Avenue in front of the New York Public Library, the truck is depicted in the photo, below. The truck was equipped with a radio and two tall masts to support the antennae. The impracticability of the use of the truck in areas with low hanging wires, overpasses, bridges, etc. seems obvious, but it was a step forward for its time.

In February of 1921, the PDNY experimented in broadcasting alarms for stolen vehicles to outside police departments, within a 250 to 300 mile radius, using wireless telegraphy.

Once again, the need for a more practical system to supplement, or replace, wireless telegraphy would be needed. In a 1937 article, Captain Gerald S. Morris, Supt. of Telegraph, wrote that the PDNY was the first in the country to use a “radio” as in 1916, a transmitter was installed in Headquarters that allowed for messages via “wireless telegraphy” to be broadcast to department boats. Using the terminology of the era, Capt. Morris’ use of the term “wireless telegraphy” synonymously with the word “radio,” if taken out of context, may lead some to believe that radio, in today’s usage, meant the wireless transmission of voice, which is not the case.

Patrol Telephone Booths

Used in the same period as the above methods of communication, another method utilizing the telephone were the PDNY’s “Patrol Telephone Booths,” which were located in the outer boroughs. According to the ARPDNY for 1922, there were 161 booths in operation. The report describes the buildings as “practically sub-stations” that were “substationally built 6 x 8 feet, painted green, with a conspicuous sign on top, with public telephone call number. They are equipped with a direct line to the police station, and also with public exchange telephone line. A motorcycle Patrolman is assigned to each to respond to call requiring police action.” PC Woods declared that the use of the Patrol Telephone Booths reduced response time from forty-five minutes to six. The decline in the use of these booths directly correlated to the increase in density as the outer boroughs became more densely populated.

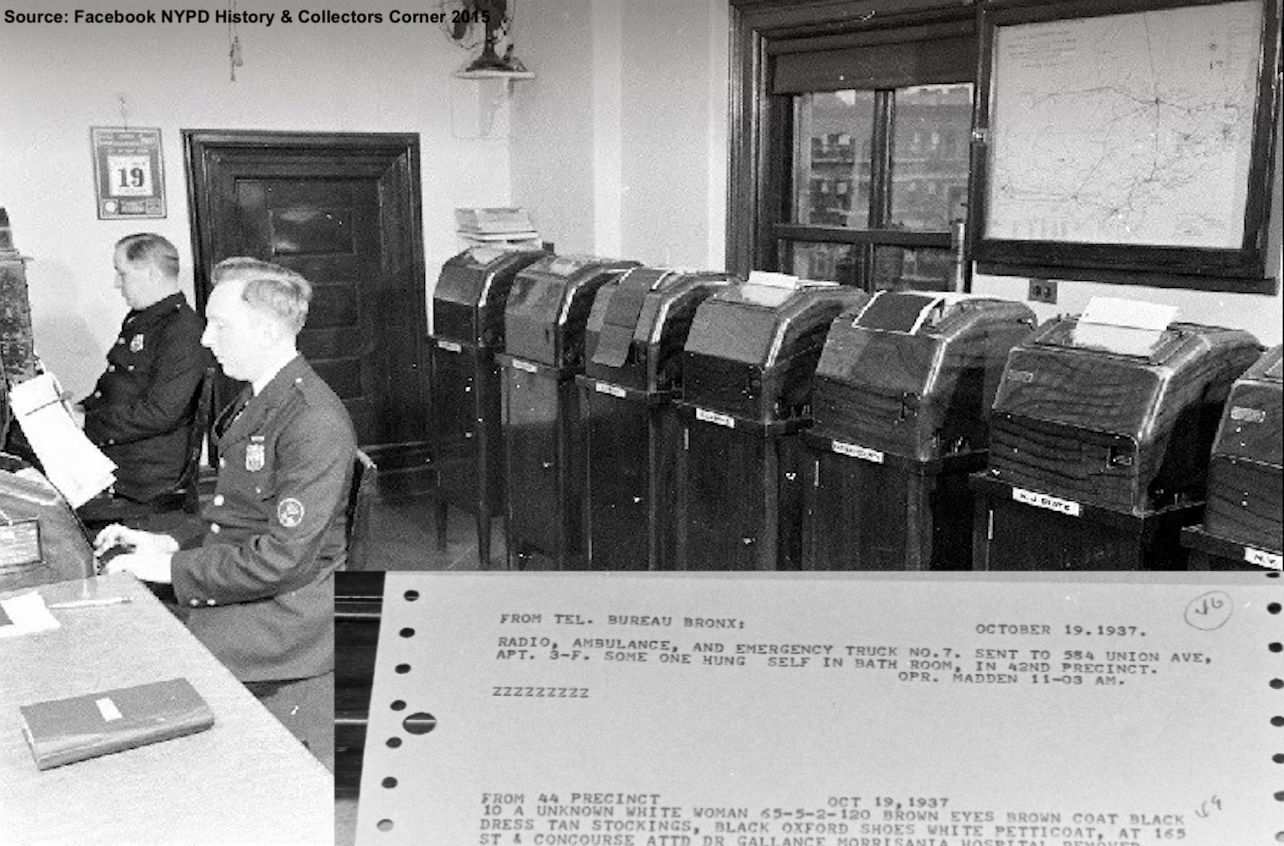

The Use of the Teletypewriter

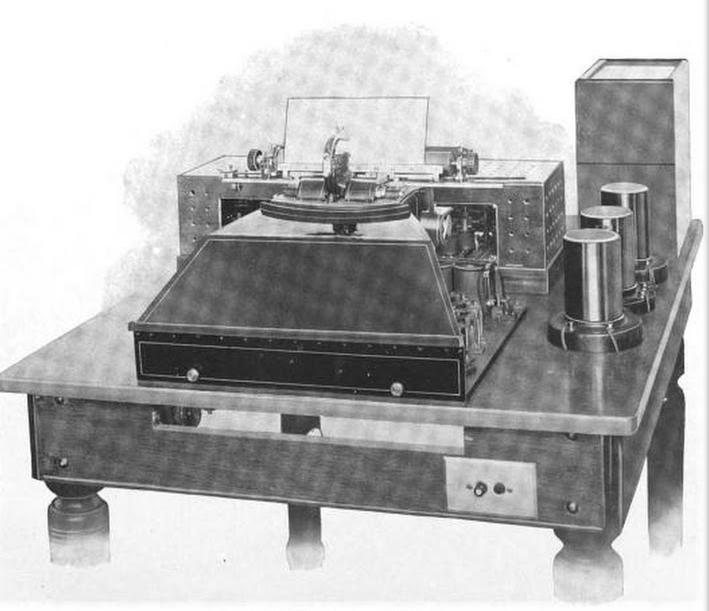

As early as 1847, experiments were underway to transmit images via telegraph wires.

In his 1902 address to the membership of the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), the President of the IACP spoke of the “novel” concept of transmitting photographs by telegraph lines [Note: Think “Fax” (Facsimile)] and opined that further experimentation with this developing technology may someday be accessible to police, and be an invaluable aid in police work. The first successful transmission of a “phototelegraphic” image took place in October 1907 when an image of King Edward was sent from Paris to London. The following year, marked the first use of the technology by a police agency when the device transmitted an image of a wanted murderer between the same two cities that resulted in his capture. The physical lines used in 1907-08 were the same lines used by telephones and teletypewriters.

In the United States, in 1915, telephone companies began to lease lines for the use of “teletypewriters” to newspapers and news services. The messages sent using teletypewriters was were called “teletypes.” Police departments began to see the advantage of this means of combining the speed of the telephone with the need for printed communications. The PDNY made note of the use of the teletype (which was first used in law enforcement in 1922), and its potential, and would later adopt use of the teletype system.

The first major disaster in NYC where the use of teletypes proved invaluable, was the 1928 subway disaster in Times Square. PC Joseph A. Warren opined that the ability to communicate clearly, accurately, and simultaneously with multiple recipients (police precincts) resulted in a perfectly coordinated response to the disaster.

The development of teletypewriters and teletypes continued through the first decade of the third millennia (2000-2010) and became the standard method of communicating information, and photographs (via Facsimile), by police agencies throughout the world. In 1983, the author was trained in the use of the New York Statewide Police Information network (NYSPIN) which was also used by the NYPD. At the time of his retirement from law enforcement in 2008, NYSPIN was in the process of being replaced by a computerized system utilizing the Internet. NYSPIN teletypes enabled teletype communication between a police department and any/all police departments in the United States and remained the standard from approximately 1938 to 2008.

Fingerprint Transmission – “Distant identification System”

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the PDNY had adopted the use of fingerprints as a means of unique identification replacing the inaccurate Bertillion System, which used various measurements of body parts to identify an individual. In 1922, at a meeting go the “International Police Conference” a report was presented on the development of a numeric system representing a unique fingerprint. Fingerprint images were sent by facsimile, but the images were often of poor quality. The numeric system was the solution.

The system was called the “Distant identification System” because it was designed to be used between police departments worldwide. The unique number assigned to an individuals set of ten fingerprints was the result of five formulas, each of which dealt with particular characteristics of fingerprints. It was proposed that, at the next annual conference, scheduled to be held in NYC, a recommendation on how to transmit these numbers between agencies would be presented.

“What’s the Deal:” With the history of police communications in New York City in the pre-voice radio era? Electricity sparked an exponential growth in the technologies available to the general public, municipalities and their emergency services departments. In some cases, NYC was first to adopt and adapt the technologies. In other cases, the technologies were first used, and proven, elsewhere. All of the advancements changed the nature of the city and its police force improving, with each step, efficiency and services delivered.

Questions, Comments, Input? Feel free to “Contact Us” using the form on the Home Page

The voice radio era was on the horizon and will be covered in Part 2 of this article.

![]()

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.