![]()

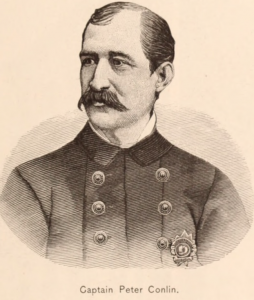

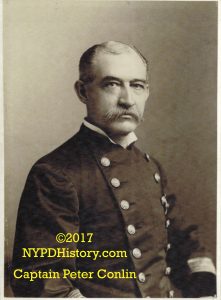

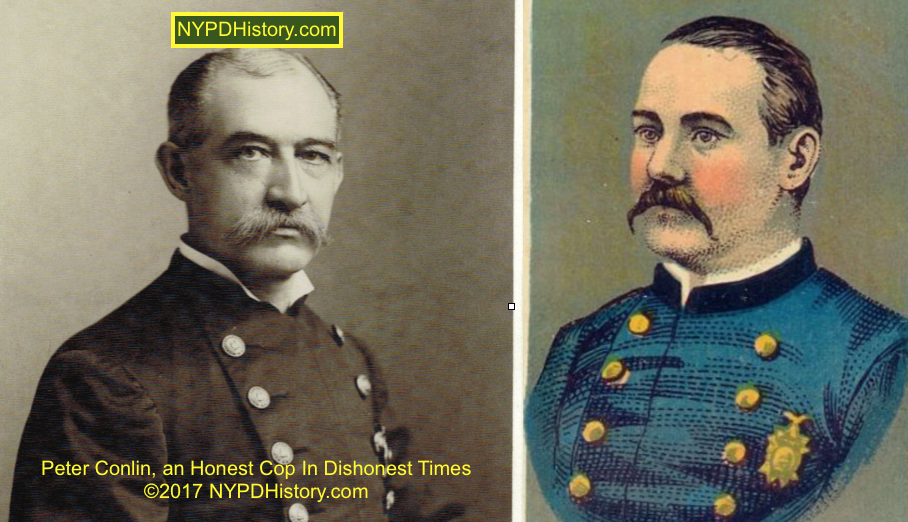

In the preceding blog post the post-Civil War career of Captain Edward Carpenter, whose career was tainted by a conviction for bribery in an era when the system was corrupt and corruption was the system, was examined. Carpenter’s career ended in shame. By contrast, the career of another post-Civil War Captain, that of Peter Conlin, stands as an example of an incorruptible man who rose through the ranks to lead the Police department of the City of New York.

Peter Conlin was born in New York City in 1841 at the corner of Essex and Delancey, Streets in Manhattan to Irish immigrant parents who moved to the city from Albany, New York. At the onset of the Civil War, when President Abraham Lincoln made a call for troops, Conlin enlisted (April 1861) as a Private in Company G, Twelfth New York Regiment, New York State (NYS) Militia, also known as the Irish Brigade. In September 1861, after reenlisting, Conlin advanced to the rank of Captain in Company E, Sixty-ninth Regiment, NYS Volunteers. Conlin was “in command of his company during the whole of McClellan’s retreat to Hampton’s Landing” (Virginia). In July 1862, Conlin was forced to resign from military service as a result of injuries sustained during the course of his eighth battle, but his public service continued for another five decades.

After his military service, Conlin had several jobs. Conlin served as Deputy Collector of Internal Revenue in Louisiana and opened a hotel in Newburgh, New York before returning to New York City.

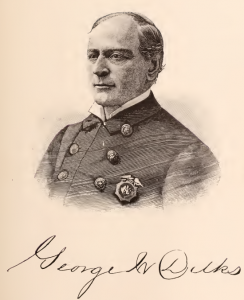

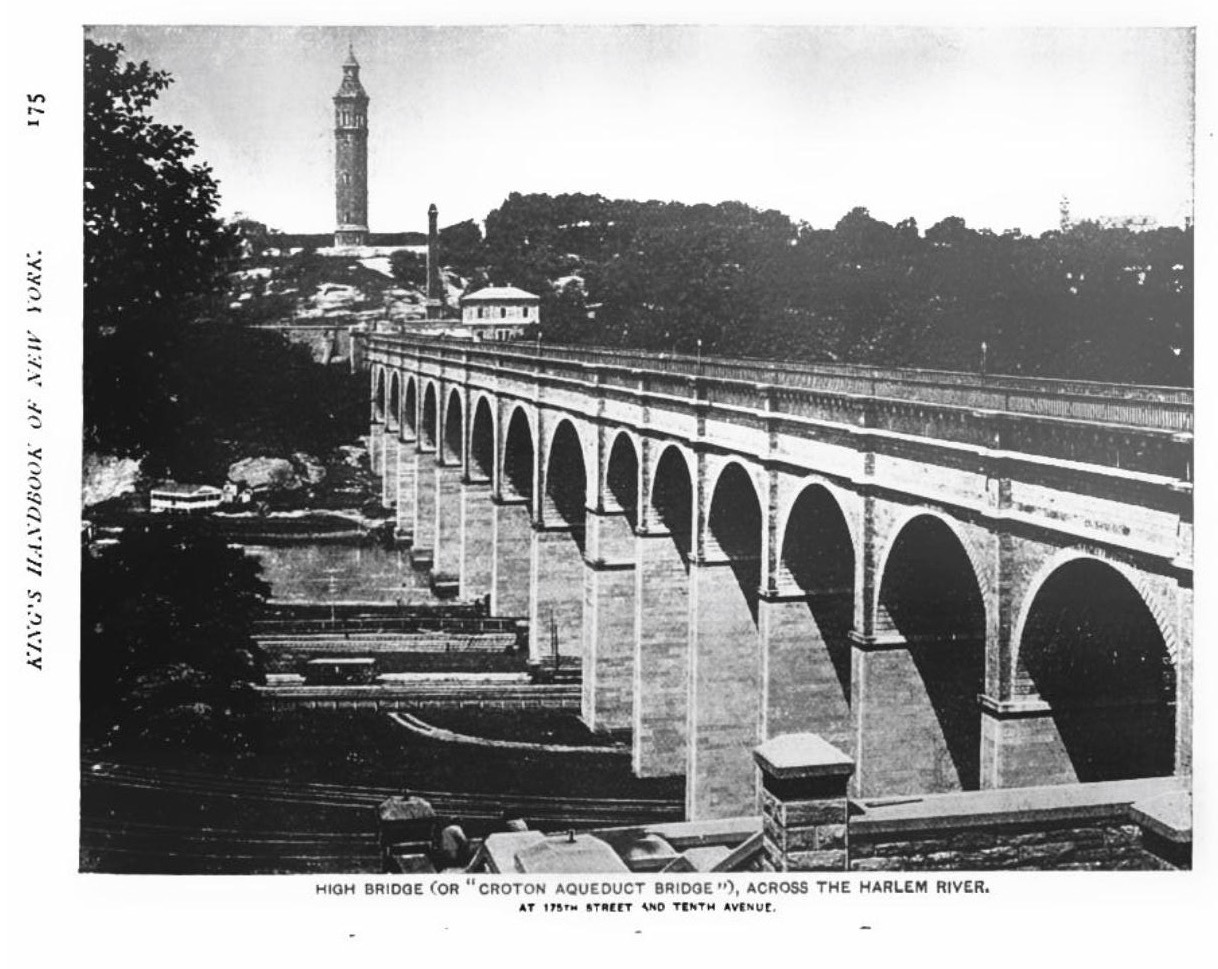

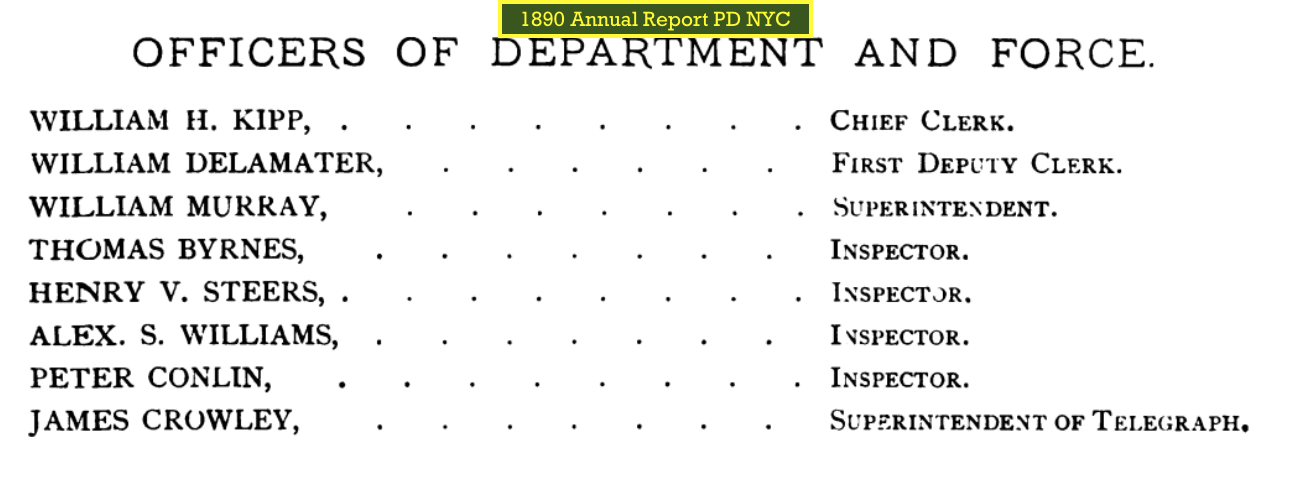

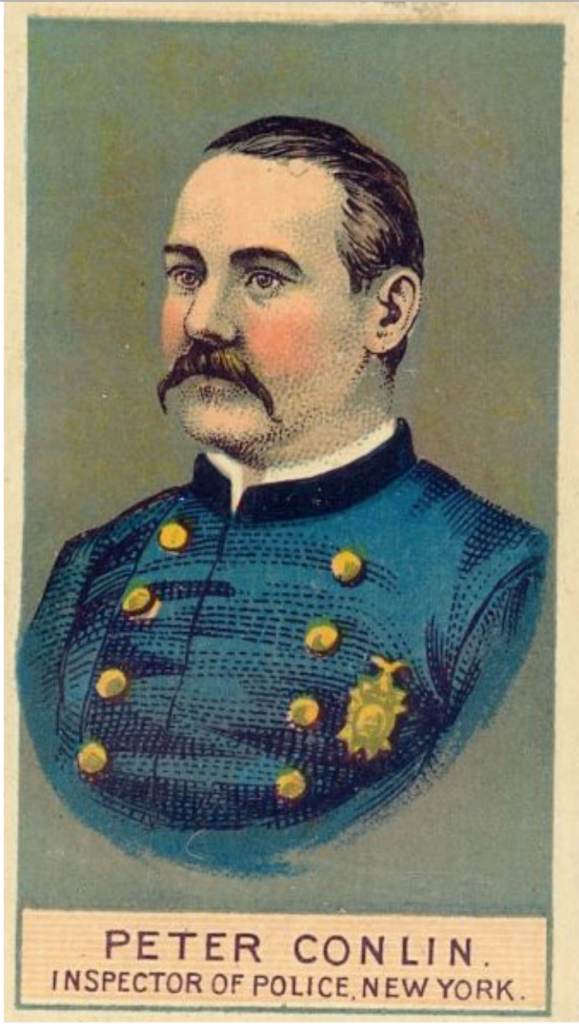

In July 1869, Conlin joined the police force and advanced through the ranks, serving as Roundsman (1872) – today’s equivalent rank of Sergeant, (1876) – today’s equivalent rank of Lieutenant, and Captain (1884). In 1885, Captain Conlin was the Commanding Officer of the Highbridge Precinct, in the Third Inspection District, under Inspector George Washington Dilks. In addition to many military veteran and fraternal organization, Conlin was a Free and Accepted Mason and lived life as an “upright man.”

In January 1881, Sergeant Conlin resided at 216 East 118th St, earned a salary of $1,600 per annum, and was second in command to Captain Edward Walsh, in the Twenty-sixth Precinct (432 East 88th St. Station-house). On August 9, 1887, Conlin’s promotion was challenged by Inspector Alexander S. “Clubber” Williams who filed a lawsuit claiming that he should have seniority over Conlin. Williams claimed that he sworn in as Inspector prior to Conlin, who was away on vacation, and therefore had seniority. The claim was dismissed by a judge. In August 1894, Conlin, a humble man, quietly had sewn a fifth service strip on the cuff of his uniform, each denoting five years of service.

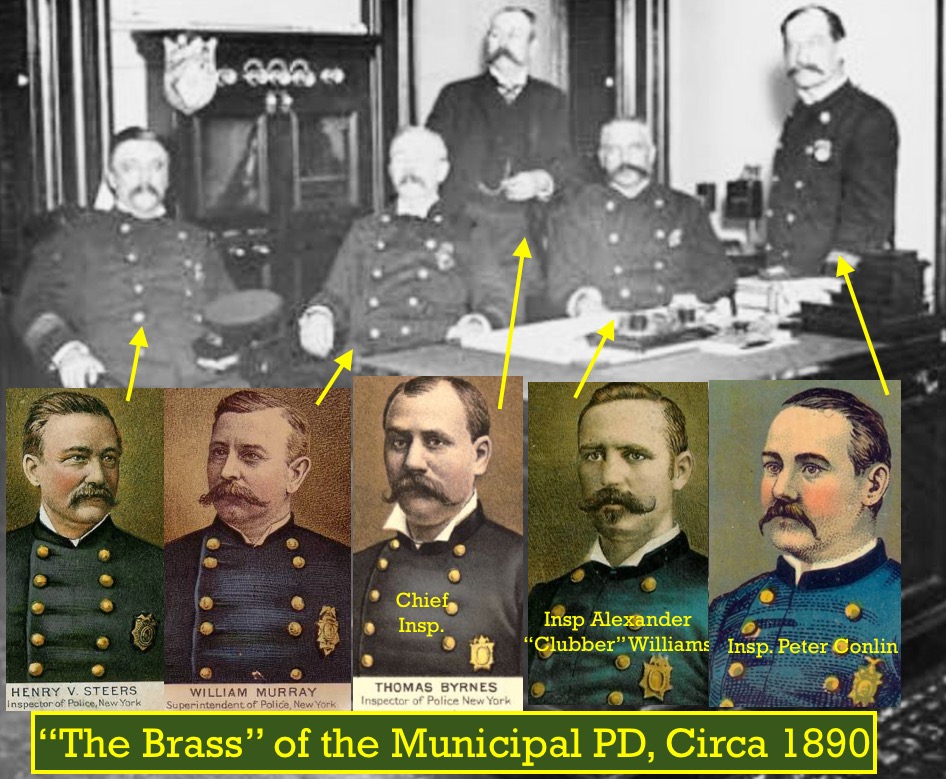

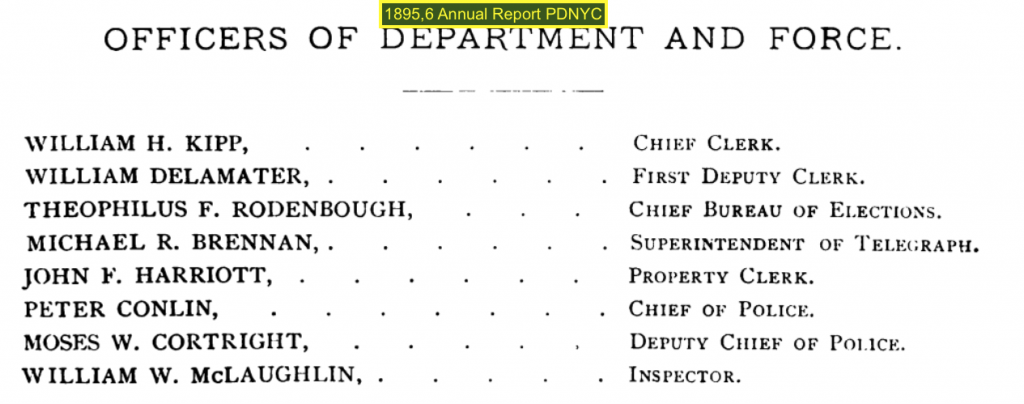

On October 31, 1892, Conlin was promoted to Chief Inspector – equivalent of today’s rank of Chief of Police, thus succeeding Inspector Henry Steers, who resigned, the position. Conlin served as Chief Inspector for five months when the position was abolished by NYS Legislature. In April 1895, Conlin filed a claim with the NYC Controller for $3,000 claiming back pay for serving as Chief Inspector since February 1893. In an article published in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper on April 17, 1895, it was reported that Conlin claimed “he had been illegally deprived of the chief inspectorship and the emoluments attached by the act of the legislature abolishing the office two years ago.”

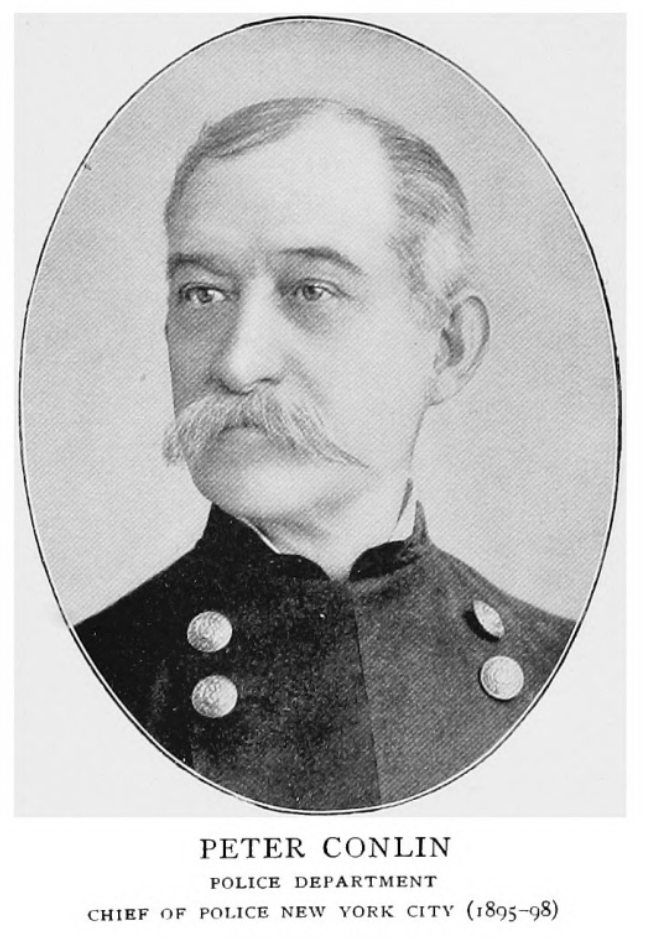

In December 1895, the same newspaper praised the Commissioners of Police for elevating Conlin to the office of Chief Inspector. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle rightfully noted that in an era of unprecedented corruption, when the department was being “searched as with a fine-toothed comb,” Conlin “kept himself free from the smirch of contamination and no one was able to point to aught that he had done which was not manly, honest, and straightforward.”

Perhaps it was Chief Inspector Conlin’s military background that prompted him to promulgate orders, and training to support the same, whereby military deportment was brought to the force. On February 2, 1896, the New York Herald reported that when a subordinate in rank meets a superior office, in an effort to “do away with the slovenly conduct on the part of patrolmen,” “they must halt, face about, stand at attention, and salute – hand at helmet peak – until the officer has passed,” adding, “even if the unusual salute burst the buttons of the coats of the fattest ‘coppers’ on duty.” Blaming the Captains for the unprofessional demeanor and appearance of those under their command, the same article reported that Chief Conlin said, “I have drawn up a code of rules which I expect will be strictly enforced hereafter in every station house in the city.”

As was the case with his predecessors and successors, in March 1896, Chief Conlin plead with the Board of Police Commissioners, the Mayor and the Board of Alderman – today’s City Council, for increased manpower. Conlin cited the increase in population and tax base, and compared the fact that the city had one officer for every five-hundred citizens to the same ratio of earlier days, and to that of other contemporary cities here and abroad. The legislators and Governor of NYS agreed with Chief Conlin, and passed a law, effective May 15, 1896, approving the addition of eight hundred men to the force.

The following excerpt from the City Record in connection with the law makes for an interesting read and will be incorporated herein.

On December 1, 1896, at 1 Madison Avenue, Manhattan, Conlin took the stand before the Lexow Committee, a panel assembled by the NYS Legislature, and headed by NYS Senator Clarence Lexow, of Rockland County. The special committee was formed to investigate corruption and graft within the police department. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Conlin was summoned as a witness “called on the behalf of the committee” and provided testimony about laws, regulations, practices, tradition, and corrupt practices. According to an article, published n June 1, 1806, Conlin also had “the distinction of being one of the few officials in the policed department who passed through the ordeal of the Lexow investigation with out having even a finer pointed at him or a hint made that he was anything gut an honest man. This stands in contrast to the career, and outcome of the Lexow investigation, of Captain Edward Carpenter, the subject of a prior article on this site.

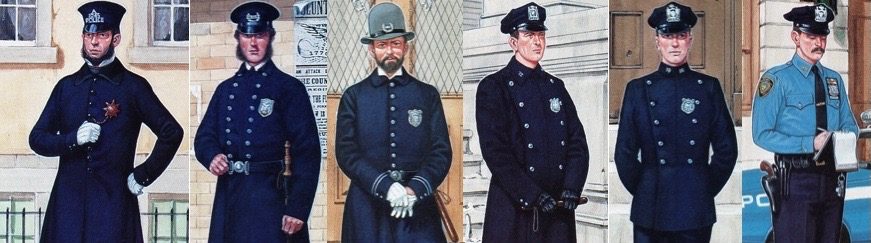

“Everyone loves a parade,” and NYC had a tradition of hosting an Annual Police Parade, typically in the month of May, where the department wore their finest uniforms and performed intricate formations while marching and showcasing new units and equipment. The parades were also the venue for the annual awarding of medals to officers for bravery, valor and excellence. However, in light of the Lexow Committee investigation, the parade was not held in 1895.

On June 1, 1896, Chief Conlin, riding a spectacular horse named “Prince,” led the 2,200 men of department up Broadway. Missing from the parade were many of the familiar faces of previous years including Thomas F. Byrnes, Alexander Williams, and fifteen other Inspectors and Captains who were either retired or implicated by Lexow. The recently established Bicycle Squad was on parade for the first time and the officers wore, for the first time their “new light weight summer helmets.” Regiments were lead by Inspectors, followed by the men under their command.

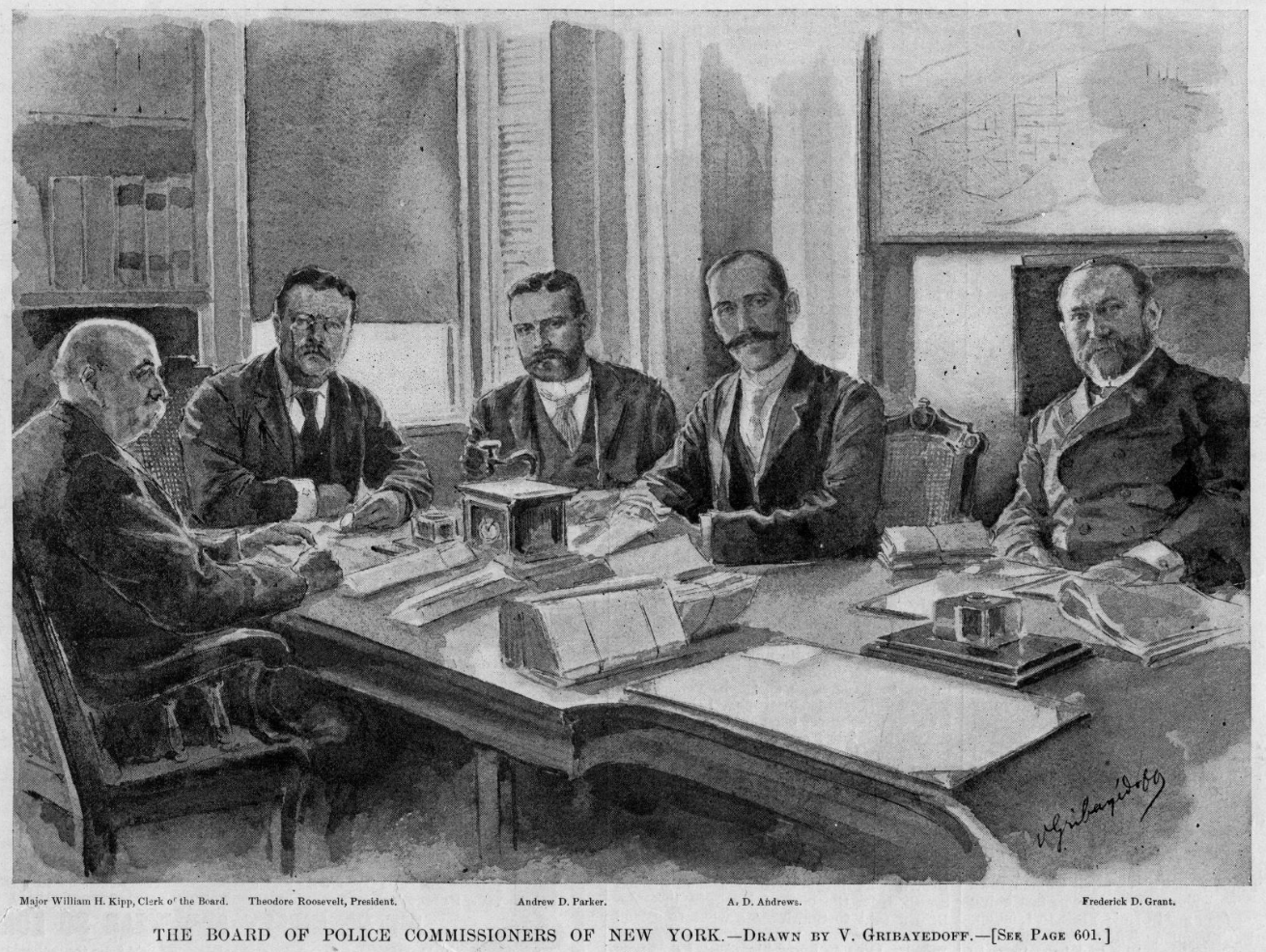

On August 25, 1897, Chief Conlin, age fifty-six, was worn down by disagreements with the politically driven Board of Commissioners, appointed by Mayor William Strong, and applied to the Board of Commissioners for retirement. His application was accepted at a pension of $3,000 per annum. The President of the Board was Theodore Roosevelt and the three, bi-partisan Commissioners were: Andrew Parker, A. D. Andrews, Frederick D. Grant, with Chief Conlin acting as a tie-breaker. Major William Kipp was the Clerk of the Board of Commissioners.

Conlin just returned from two weeks vacation and repeatedly, even on the morning that he submitted his papers, denied that he planned to retire. In a move that came as a surprise to all, the Board ignored the law and passed over Deputy Chief Moses Cortright, appointing Acting Inspector John McCullagh as Conlin’s successor. McCullagh would remain in the position through the city’s transformation into the Greater City of New York, commonly referred to as the “Consolidation.” On January 1, 1898, by an act of NYS Legislature, New York City (Manhattan) transformed (consolidated) into the city of five boroughs that we know today. McCullagh was appointed Patrolman in 1870 and, as Captain, commanded three precincts.

In what seems to be the modus operandi for the retirements of police chiefs serving a single commissioner, or a board of commissioners, the individual members of the board publicly heaped praise on Conlin, whose job they made unbearable. Conlin, stated “I thank you gentlemen for your courtesy and if I can be of any assistance in the future to the incoming chief, I will be only too glad.” Immediately thereafter, Ex-Chief Conlin remarked to the press: “I was tired. Very tired. I couldn’t stand the thought that matters were formulating against me for the purpose of making it unpleasant for me as chief of police.” He continued “I feel like a different man already. I don’t want to hear the word ‘police’ mentioned to me any more.”

The press was supportive of Conlin’s decision to retire and praised him for his honest, earnest work and success in restoring professionalism and honesty to a department which had been demoralized and turned on end by the findings of the Lexow Committee.

Conlin’s wish to never hear of the word “police” again did not last long. In December 1897, he filed an application for mandamus compelling the Board of Police Commissioners to pay a bill for the dredging of a human head from there East River, in connection with an murder investigation. The Board previously approved the expenditure, but the Treasurer of the Board refused to pay, relying on a theory that Chief Conlin did not have the authority to authorize the expense.

In 1897, Conlin was elected President of the Veteran Association of the Sixty-ninth New York Volunteers. In 1898, Conlin, who had a summer cottage in Center Moriches, Long Island, moved there permanently, and purchased land, extending his to the shore of the Senix River. In March 1899, Conlin was the Democratic candidate for Justice of the Peace in Center Moriches. In 1901, it was reported that Conlin was “under favorable consideration” for the position of First Deputy Commissioner of the Police Department of greater New York, but he declined the position.

More than one year after his wife’s death, Conlin, then an “invalid,” was living with the eldest of three daughters in Walpole, Massachusetts when he died, on October 23, 1905.

The Lexow Committee’s investigation resulted in the prosecution of several high-ranking police officials and forced retirement of many others. Chief Conlin’s tenure as head of the department was cut short due to interference from the politically motivated actions of a partisan Police Board. Chief Conlin did, however, restore faith in the department in the eyes of the public and the press. This Civil War hero was one of many officers who served their nation in their time of need and his unblemished career serves as a shining example for those officers who aspire to rise through the ranks, without getting caught-up in politics and graft.

![]()

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.