Until 1898, the city as we know it today, with five boroughs, and one police department, all governed by a mayor from City Hall, did not exist. New York City was coterminous with the Island of Manhattan. In fact, while policing dates back to the time of the Dutch and English colonization of Manhattan in the early 17th century, the PDNY, more commonly known by the acronym NYPD, is regarded by many police historians to have been “born” in 1898.

Until 1898, the city as we know it today, with five boroughs, and one police department, all governed by a mayor from City Hall, did not exist. New York City was coterminous with the Island of Manhattan. In fact, while policing dates back to the time of the Dutch and English colonization of Manhattan in the early 17th century, the PDNY, more commonly known by the acronym NYPD, is regarded by many police historians to have been “born” in 1898.

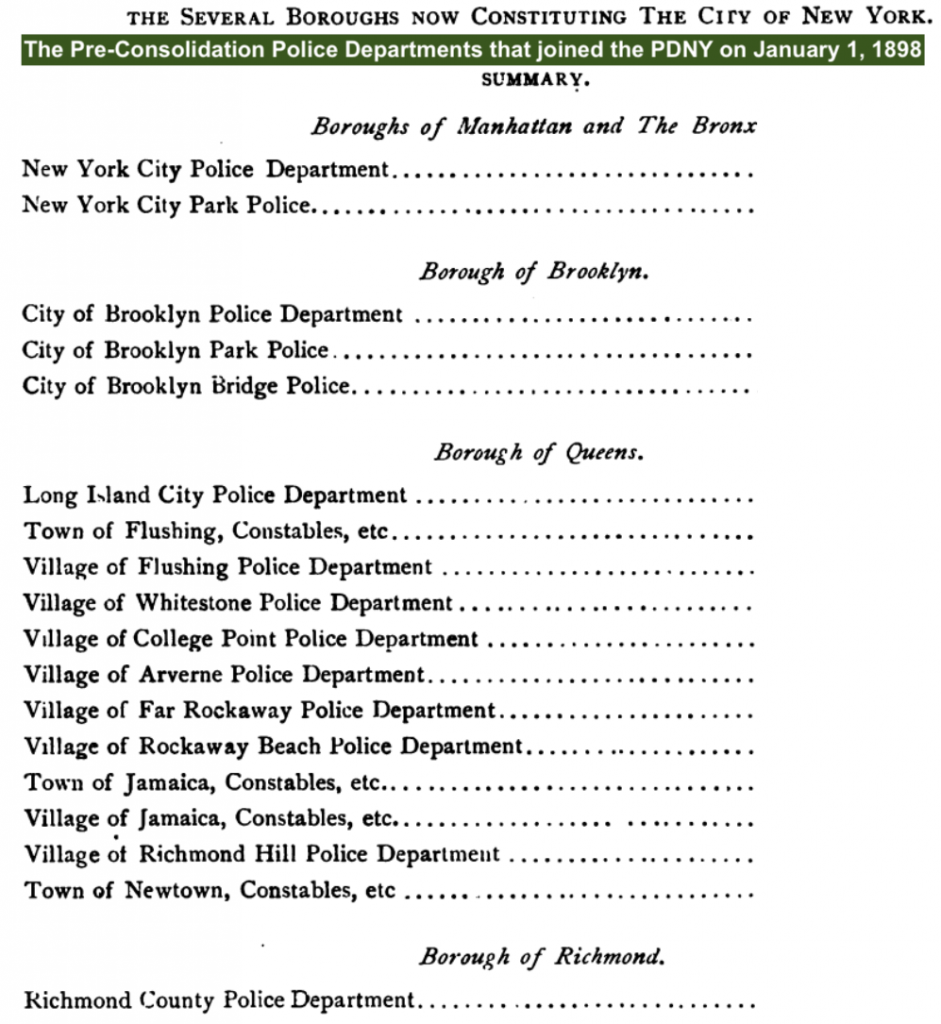

On January 1, 1898, the Greater New York Charter, as written in 1897, and commonly referred to as the “Consolidation Act” took effect. The charter created the Greater City of New York (NYC). Prior to consolidation, eighteen police departments, and various other government entities, in the counties of Richmond (Staten Island), Queens, Kings (Brooklyn), and the towns and villages in the area of The Bronx west of the Bronx River, as well as the City of Brooklyn PD, joined their respective counterparts of NYC (Manhattan). Previously, in 1874, the towns and villages west of the Bronx River were “annexed” and policed by NYC. The Bronx became a county in 1913.

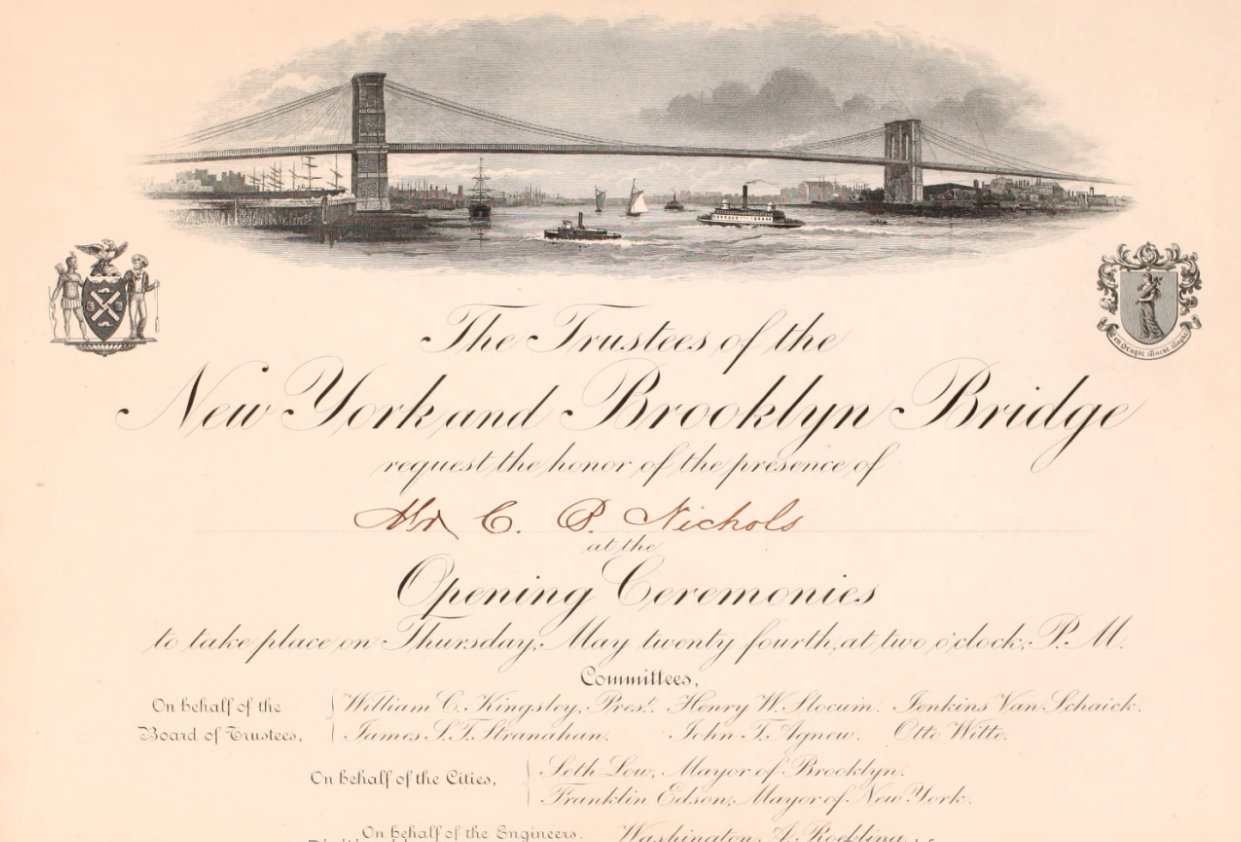

This is the first known history ever written of one of the pre-Consolidation Era police departments, which was known as the “Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridge (MBB) Police Department” (MBBPD). The MBBPD was created and governed by the Board of Trustees of the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridge Company (the Trustees) and existed from 1883-1898. In 1883, when opened, the MBB, now referred to simply as the “Brooklyn Bridge,” carried pedestrians, horse and horse carriage traffic on the promenade, and cable-driven rail cars which transported passengers from large terminals on each side of the East River. Policing the terminals, ticket booths, promenade, rail cars, etc. 135 feet above a busy shipping lane were some of the challenges faced by the bridge officers.

Like many police departments, both before and after consolidation, political influence by various governing bodies played a heavy influence in every aspect of the MBBPD, from appointments, promotions, discipline, dismissals, to scheduling and working conditions. From “day one” of the MBBPD’s existence, the political influence in the very formation of the department and the hiring of its officers set the stage for a department that never rose above mediocrity. The history of the MBBPD is not one laced with stories of professionalism, distinction and tales of heroism. Nonetheless, the story is fascinating, a part of the NYPD’s history, and heretofore has never been compiled or told.

Background

On April 16, 1867, sixteen years before the bridge was completed and opened, the New York State (NYS) Legislature enacted legislation to “incorporate the New York Bridge Company for the purpose of constructing and maintaining a bridge over the East River, between the cities of New York and Brooklyn.” Relating to the policing of the bridge, the legislation set forth that concurrent jurisdiction between the City and County of New York and the County of Kings (Brooklyn) would exist for any arrests and prosecutions relating to crimes committed on the bridge. It also called for the Commissioners of the Metropolitan Police District, which encompassed NYC and Brooklyn from 1853-1871, to provide an adequate number of officers to police the bridge, the costs for which were to be shared by both cities. However, in 1880, it was decided that the Metropolitan PD would not police the bridge.

In 1874, the NYS Legislature enacted legislation to permit the Board of Trustees to “appoint an adequate force, and regulate and direct the same…the policemen so appointed shall have and possess all the powers of policemen in the cities of New York and Brooklyn.”

In 1883, Brooklyn Mayor Seth Low, a member of the Board of Trustees, signed a resolution governing the candidates for employment of the MBB, which included the police force. The adopted resolution provided that no arbitrary age limit shall apply to any prospective employee who had previously been honorably discharged as a soldier or sailor in the service of the country. This provision would allow for the hiring of veterans of the Civil War in any capacity, including police officers.

Candidates for the MBBPD were to be hired directly by the Trustees and were employees of the MBB Company, not the Cities of New York and Brooklyn. The MBB was a self-governed quasi-governmental entity which raised money from trolley ticket sales, rents from utility companies for running wires along the bridge, etc. The salaries of the bridge officers was paid by the trolley ticket receipts. Other salaries and expenses were paid from other income.

Civil War Veterans of the Bridge Force

Two Civil War Veterans were identified as having been appointed to the bridge force. They were Ptl. John Kenney, who served as a Private in the Sixty-First New York Infantry earned a remarkable record in battles from Bull Run through Appomattox. “This hero of fifty battles is as erect and vigorous as ever, and looks good for another war, if called upon.”

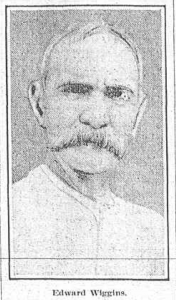

Another veteran appointed under the 1883 provision was Roundsman Edward Wiggins. Wiggins served the bridge force from the time of its inception in 1883 to the time of consolidation in 1898, when he retired. It was reported that Wiggins never missed a roll call, never reported sick, and had an enviable record of service under Sergeant Phillips.

Formative Years- Fraught With Criticism

The command structure of the bridge force included one Captain (Capt.), and a number of Patrolmen. Headquarters of the bridge force was located in the basement of 179 Washington Street, Brooklyn, a building used for decades as the Executive Building of the New York and Brooklyn Bridge Company.

With great celebration and fanfare, the New York and Brooklyn Bridge opened on May 24, 1883, at 2:00 pm. MBBPD Ptl. Luke B. Duryea was on duty and stopped the first carriage to cross the bridge from the Brooklyn side for the purpose of “obtaining an autograph from the driver, Charles C. Overton of Coney Island.”

Many of the officers hired for the bridge force, were “washouts” of either the PDNY or the City of Brooklyn Department of Police and Excise (BPD). One of the initial candidates for the captaincy was “ex-Capt. Riley, who was dismissed from the Brooklyn force by Commissioner Jourdan for overstepping his authority.”

On May 29, 1883, the Trustees appointed the first Captain of the MBBPD, James Ward. “Chief Engineer and Superintendent” of the bridge company, C.C. Martin, took criticism for appointing Capt. Ward. Ward was an ex-Sergeant of the BPD’s 6th Precinct, and was recently demoted from the rank of Sergeant (equivalent to today’s rank of Captain) to Patrolman by the Superintendent of the BPD, General James Jourdan, for incompetence. Ward resigned from the BPD, rather than accept the demotion. Brooklyn Mayor Seth Low told the Trustees that the appointment of Capt. Ward was “an unfortunate one.”

In light of the questionable character of the candidates hired by the Trustees, the fact that no police training was required, and their appearance of the men as that of Special Officers, criticism of the new force was swift, harsh and plentiful. The criticism came not only from citizens and newspapers, but from the MBBPD’s counterparts in the PDNY & BPD.

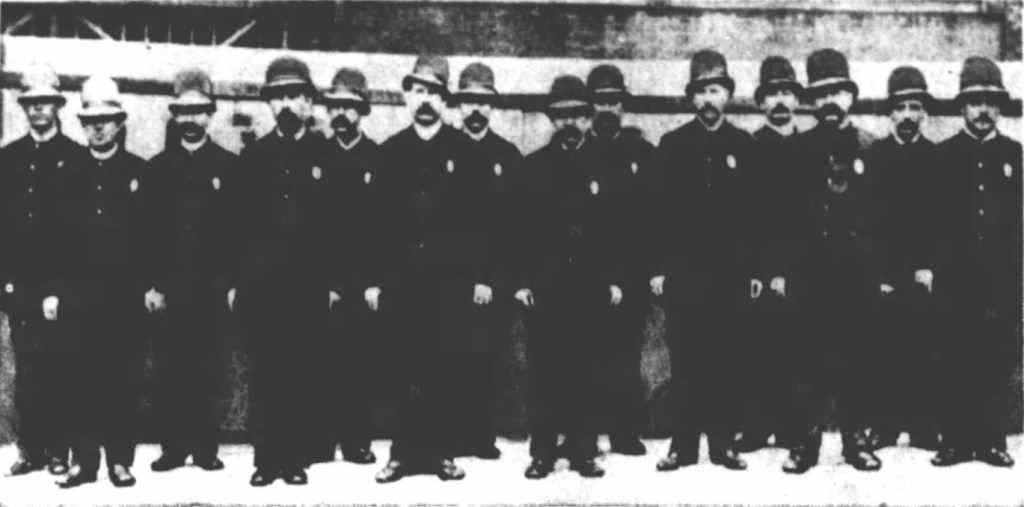

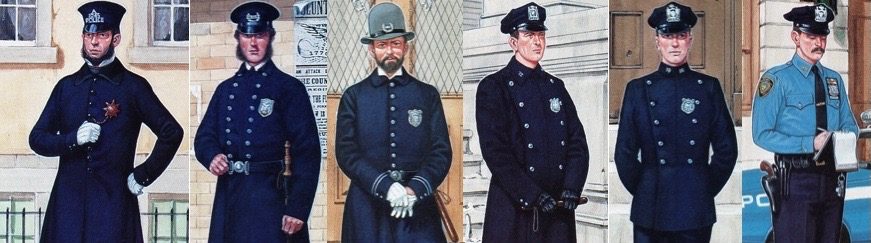

The MBBPD initially consisted of 22 Patrolmen and one Captain. The Patrolmen worked 12 hour tours from 6:00 am to 6:00 pm and 6:00 pm to 6:00 am, with 10 men on duty during each shift. Officers from other departments opined that the hours were too long and were contrary to the good judgement of their superior officers who felt that such long tours were ineffective at rendering effective police service. At the time, the BPD officers worked 6 hour tours, from 6:00 am to noon and then 6:00 pm to midnight. The only known photo of the group of New York and Manhattan Bridge PD officers!

The only known photo of the group of New York and Manhattan Bridge PD officers!

Roundsman William Brophy was a member of the MBBPD who was with the force from its inception. According to one newspaper account, he stood 6’ 4” and had a 48” chest. [Note: Brophy can be seen standing on the right side (below) of the 1883 group photo.]

The shields depicted below have never been seen online. This is the first time that the actual shields have been shared with the public. All Rights Reserved. Do not duplicate without expressed permission.

Newspapers wrote that the “men for the most part are rather below the standard, in physical appearance…for appointment on the regular force” (PDNY and BPD). The article continued “Some of them are also beyond the age for proper discharge of active duty. It is believed that the squad will have to be reorganized before it can inspire much confidence in the minds of the public.”

In the same article, an officer from another force, commented on the grand size and importance of the new bridge and said that the men of the bridge force should be “tall men, strong of arm, firm of purpose and cool headed. One such man is worth half a dozen commonplace men.”

BPD Police Commissioner (PC) James Jourdan offered a reporter a stinging rebuke of the bridge force stating that there was no need for the force as the bridge could be patrolled by both the PDNY and BPD; that the men of the bridge force “have not the moral strength behind them that the regular force has, and never will have;” and that the “work of green and inexperienced men is simply absurd, and will not be successful.” PC Jourdan concluded his statement with the foresight that the bridge officers were not going to be able “to patrol any distance in the Winter, with the ice, snow and wind that it brings. There will have to be sentry boxes put up” and closed by stating “To properly patrol the structure, so that public safety is assured, is by no means an easy as a task as it would seem.”

Superintendent of Police of the BPD, Patrick Campbell, compounded the criticism by telling the same reporter, in the same article, that the men of the bridge force were inexperienced, and appointed “because the Bridge Trustees wanted to give men who were thrown out of work a chance to earn a living.”

Within the first week of the bridge’s opening, newspapers reported that swarms of pedestrians flocked to the bridge to experience the vistas from what was the highest point in both cities at the time. The throngs of people were the delight of pickpockets and that the newly minted MBBPD patrolmen appeared to be overwhelmed. In fact, detectives of both cities made arrests of known pickpockets on both sides of the bridge while the bridge officers had not made any arrests of pickpockets on the bridge. Within the first days of the second weeks, the bridge was such an attraction that foot traffic was 1,200 pedestrians per hour. At times, “ruffians” caused panic and women and children were trampled and injured.

One article noted that only some of the patrolmen wore shields, which were inscribed “New York and Brooklyn Bridge Police;” that the patrolmen had not yet been assigned to posts; and that a captain had not yet been appointed. According to another news account, a Sergeant of the New York City police force said that the “bridge was overrun with thieves and other disreputable characters” and that the Trustees needed to increase the number of patrolmen in the bridge force, and on the bridge at any given time, from the forty now on the force. Overall, the press reported that the “police service on the bridge is said not to be as satisfactory as desired.”

The first “runaway” (a term used to describe a horse, or horse drawn vehicle that is out of human control) occurred on May 26, 1883 when a team of horses became separated from a barouche (a type of carriage), however no injuries occurred. In the era, runaways were a major danger and the frequent cause of injuries and deaths.

In June 1883, the Trustees approved a resolution to move the office of the Board of Trustees to a 22 Sands St., Brooklyn. In July 1883, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that “The bridge police now occupy their new quarters in the building on Sands St;” that “workmen were busily engaged in making permanent arrangements for the occupancy of rooms by the force. Captain Ward’s desk and the furniture of the rooms were moved from the first floor yesterday” to the basement. The force occupied both the basement and the first floor.

In the same month, it was reported that “Babcock Fire Extinguishers” were placed in strategic locations along the bridge and that an engine “will be kept in Police headquarters” in case of fire.

No evidence was found regarding a system of merit whereby bridge officers who performed acts of meritorious conduct or heroism were rewarded by commendation or medals. No incidents of meritorious or heroic acts, beyond stopping runaway horses, or teams of horses, was disclosed.

PDNY and BPD officers were frequently commended, and earned medals, for stopping runaways, a practice that often resulted in injuries and deaths to officers. For the officers of the PDNY and BPD, the act of stopping runaways was, however, cause for commendation or medals, including those of the highest order. In 1896, for example, there were 42 runaways on the bridge roadway which caused 5 serious and 14 slight injuries. In 1898, 497 “runaway teams” were reported by the PDNY and 3 officers received Honorable Mention, a high order of merit, for stopping runaways.

Due to the ever-increasing throngs of pedestrians and other traffic on the bridge, workers and bridge patrolmen had expressed the opinion that there were not enough patrolmen to regulate the crowds and feared that a calamity was imminent.

Disaster Strikes the Bridge

One week after the bridge’s celebrated opening, on Wednesday May 30, the cities were observing Decoration Day, known today as Memorial Day. The rainy weather in the early morning cleared and, once again, crowds from near and far flocked to experience the bridge and to take in the unique views of the cities and harbors.

As the crowds moved through the ticket booths on the NYC promenade and entered the bridge, a bottleneck occurred on a flight of stairs. As people began to be crushed, women screamed, people fell, were trampled, and a railing gave way. In the end, hundreds were injured and 12 had perished. News of the tragedy spread through the cities and beyond causing concerned friends and relatives to race to both ends of the bridge to get information on missing loved ones.

Newspapers and public officials quickly placed the blame for the tragedy on the Trustees and the MBBPD for not having a sufficient number of officers; for not assigning officers to posts where they were most needed; and for permitting people to congregate in dense crowds, rather than “move along.” There were only 22 officers on duty (12 in uniform and 10 in civilian clothes) at the time of the incident, many of whom were stationed at the ticket booths.

After the disaster, Chief Engineer and Superintendent Martin came under criticism for, and took responsibility for, not properly policing the bridge at the time of the incident.

Politics and Policing

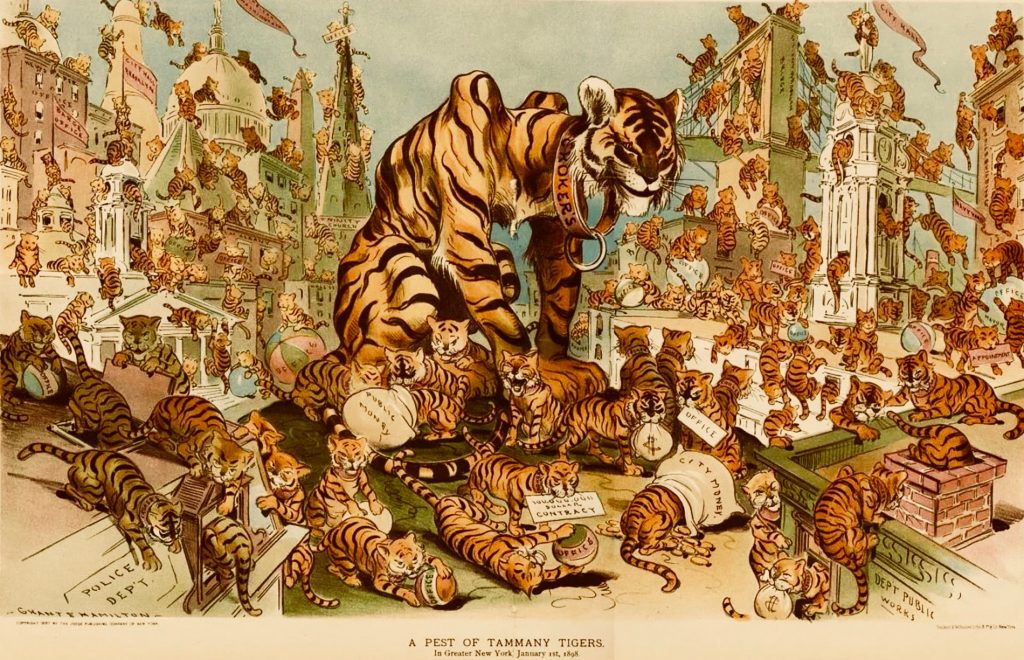

From the time of the formation of the Dutch and English colonization of today’s NYC, the City Watch, which provided law enforcement services, was influenced by politics. In the post-Civil War era, the Democrat Party political machine that was called “Tammany Hall” (their mascot was the “Tammany Tiger”) had their figurative claws into every aspect of elections, appointments, politics, policing and everyday life in the city. Tammany, however, was a corrupt organization akin to an organized crime network and graft, bribery, intimidation, and undue influence were their modus operandi. Other political parties were not exempt from similar actions, however they paled in comparison to Tammany.

As mentioned above, the MBBPD was created by the Trustees of the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridge Company, not a government entity such as a city, town, or village. The police officers derived their authority by way of NYS legislation. Many of the Trustees, however, were either politicians themselves, members of Tammany Hall, or carried the work of politicians to the bridge company.

Regarding political influence of Capt. Ward, a Democrat, and member of Tammany Hall, in October 1885, two bridge officers spoke under the condition of anonymity with a reporter from the New York Times. The officers voiced their complaints about the influence of politicians over the MBBPD.

The reporter quoted one officer as having said: “We have a day watch and a night watch, and the men with politicians backin’ ‘em all get on the day platoons. The Captain (Ward) is a Democrat, and so we Republicans don’t get no show. There’s men here only a month are shown preference over them that’s been here since the bridge was opened. If we’d kick I reckon he’d get others to take our place, but if the Trustees learn what he’s up to they’d see right done by us.”

In June 1881, the result of political in-fights amongst the Trustees left “the gentleman whom Tammany put in control of the great highway between the two cities” in charge of the entire operation, including the police force. Colonel Alfred Wagstaff, Jr. called each department head into his office and asked each man whether or not they recognized him as President of the bridge company and if they were prepared to obey his orders. Police Captain Ward, a Tammany man himself, passed muster.

The Trustees met on June 2, 1883. Part of the discussion concerned the disaster and changes that were needed relating to the police force. The President of the Trustees asked that several appointments of policemen be approved; and that uniforms and equipment for the police force be authorized and purchased. In the summer of 1883, the officers of the bridge force were furnished with pressed felt helmets.

One week later, the Trustees voted to remove the power of the superintendent as the sole commissioner of bridge police officers and to empower the Board of Trustees to do the same. The Trustees also adopted the rules and “regulations for the government of the police force.” The rate of speed of travel on the bridge was set as four miles per hour, with a penalty of a $25.00 fine.

In January 1887, Ptl. Frederick Richards, of 102 Ludlow St., Manhattan, a veteran of the Civil War, committed suicide by ingesting oxalic acid, which he used to polish his brass uniform buttons. Apparently suffering from alcoholism, Richards was once dismissed from the force and “had to use extraordinary influence to get reinstated.” After attending the funeral of a bridge officer who died of pneumonia, a common cause of death for the bridge officers, he had become intoxicated and was unable to report for duty. Fearing dismissal once again, and after a threat by his wife that he needed to stop drinking or she would leave him, he ended his life.

An article appearing in the New York Times on June 16, 1895, dealt squarely with the fact that political influence was responsible for the employment of the “great majority of the bridge employees.’” Regarding the MBBPD, the article indicated that “Many men from over the State have gone on the bridge police force, which numbers eighty-four patrolmen, three roundsmen, two sergeants, and one captain. They get the same pay as the New-York police and most of them think they are better off than their brother bluecoats in New-York. They think their job is cleaner, softer and easier on the feet.”

Not even Capt. Ward himself was exempt from disciplinary action. In May 1896, Capt. Ward was charged by a Trustee for allegedly having violated a rule which prohibited officers from soliciting money for political, or any other purpose. It was also alleged that Capt. Ward had formed a fund for the purpose of paying an attorney to lobby politicians in Albany for the advancement of the interests of the bridge officers.

In his defense, which was corroborated by many officers, Capt. Ward explained that it was Doorman Joseph Wicks, who had collected the money and turned it over to him; that he immediately asked for a list of names of those who contributed; and that he to sought to return the money indicating to the contributors that it was a violation of the rules and regulations.

The separation of politics from the MBBPD occurred at the time of its abolition, when, on January 1, 1898, the “Consolidation Act” resulted in creation of the Greater City of New York (five boroughs), also we know it today.

Policing the Great Bridge

The duties, and dangers met by the bridge officers were no different than those of their counterparts in the cities.

On June 26, 1883, at 4:30 am, three Arabian Camels, driven by “young lads” made their way from Coney Island to Central Park. As they entered the bridge promenade from the Brooklyn side, something startled the animals which caused them to run at a “furious rate.” Bridge Ptl. Dooley saw the animals advancing towards his post and closed the gates, preventing a possible pedestrian vs. camel collision.

In July 1883, despite the opinions of police officials on both sides of the bridge, Capt. Ward opined that he believed that “the force is now well organized and in better working order than any body of officers in the two cities. We have systematized everything, and all things requiring reports are telephoned to headquarters at once.” At the same time, renovations were being made to the first floor and basement of the MBBPD Headquarters, located on Sands Street, Brooklyn. In 1887, a news article indicated that, due to the fact that their headquarters did not have a jail cell in which to keep prisoners, prisoners were brought either to the York Street Station, Brooklyn or the Oak Street Station in Manhattan.

In November 1883, the first arrest noted for “Reckless Driving” on the bridge was that of James Barnerman of 527 Fifth Ave., Manhattan. Capt. Ward discharged him from custody with a warning.

Despite their early reputation as being a band of ruffians, Capt. Ward, in December 1883, told a reporter that while he read accounts of the same in newspapers, he never received a single complaint regarding alleged brutality. Capt. Ward encouraged the public to report any complaints.

In a bizarre incident that nearly resulted in the murder of one of the bridge force’s officers, on July 16, 1884, Ptl. John W. McKenna of the City of Brooklyn PD’s 1st Precinct, approached Capt. Ward in the bridge police headquarters. Ptl. McKenna advised Capt. Ward that his daughter, Lillie, age 23, had gone missing and that he believed she had done so at the insistence of MBBPD Roundsman Charles Heath.

Capt. Ward summoned Roundsman Heath and confronted him with the allegation. Initially, Heath denied any knowledge of Lillie, or her whereabouts. Under further questioning, Heath admitted that he had provided Lillie with money and brought her to a “house of ill repute” on the Bowery where he frequently visited her.

Upon hearing the admission, which one newspaper described as having been said “very colly (sic) and alluded to the girl contemptuously,” Ptl. McKenna drew his revolver and pointed it at Heath. Capt. Ward put himself between the men and “wrenched the weapon from McKenna’s hands.” Ptl. McKenna reportedly “calmed down” and left the MBBPD’s headquarters. Roundsman Heath was promptly discharged from the force. The City of Brooklyn and New York PD sent out general alarms to locate Lillie.

In 1886, the force was comprised of one Captain, one Sergeant, three roundsmen, one Property Clerk/Doorman and 91 Patrolmen. By 1896, a second Sergeant had been added and there were 87 Patrolmen.

On June 20, 1886, Ptl. Patrick Mulligan was knocked off a moving train car, falling onto the tracks. While he laid unconscious, the train cable ran over his foot and he lost three toes.

In August 1886, Capt. Ward praised the electric lights on the bridge would facilitate the responsibilities of his men and make the bridge safer for all who travel on the same. It was also noted that many of the officers of the MBBPD “indulged in the luxury of photographs.”

Performance

The uniformed presence of the bridge officers served as a deterrent to criminals. On average, arrests were made ranging from 200-270 per year from the 1880s through 1891. In 1889, in his report to the Trustees, President of the bridge Trustees James Howell wrote “The efficiency of the Police has been maintained, and their well-earned reputation has not been tarnished…it is an established fact that no safer place than the Bridge Promenade at all hours can be found in either city.”

| 1888 | 1891 | 1896 | |

| Total Arrests | 214 | 270 | 247 |

| Intoxication | 71 | 127 | 119 |

| Drunk & Disorderly | 46 | 37 | 19 |

| Disorderly Conduct | 24 | 32 | 26 |

| Fast Driving | 18 | 16 | 18 |

| Fighting | 11 | 10 | 8 |

| Larceny | 12 | 10 | 13 |

Other arrests, in lower numbers than those above, were regularly made for: Attempted Suicide, Lunacy, Pocket Picking, Vagrancy, and violations of bridge ordinances, and account for the difference between the numbers reported in the table and the total arrests.

Complaints by citizens ranging from discourteous treatment to assault and false arrest plagued the department. In April 1887, Brooklyn resident F.A. Davidson publicly announced that he would shoot the next bridge officer who laid “a hand on him.”

In January 1888, in light of the complaints, an article was published in a newspaper which called the question of whether or not the MBBPD should be dissolved. The paper claimed that the police of the cities of New York and Brooklyn looked with contempt on the members of the bridge force. In a letter, one citizen referred to the men of the force as “ornamental dummy policemen.” It was reported that an unidentified captain of the PDNY opined that he could do with 20 men what 96 bridge officers do; that the bridge officers were not policemen at all, but rather private watchmen paid to march around on the bridge. It was suggested that four PDNY Mounted (horse) Officers could adequately replace the 96 bridge officers.

Bridge Superintendent Martin defended his officers.

Working conditions on the bridge were not easy and were in fact dangerous to the health of the officers. Exposure to the elements appeared to have been the cause of a disproportionate amount of illness and deaths compared to those of their counterparts in city departments. Bridge officers enlisted the support of a large, influential labor union to lobby for the erection of sentry boxes along the bridge where they could seek refuge in foul weather. In the winter months, officers wore heavy chamois overcoats made from the “felted fiber of the spruce tree.” The question of sentry boxes was mentioned five years earlier, in 1883, by BPD Police Commissioner (PC) James Jourdan.

In October of 1885, the Trustees raised Capt. Ward’s salary to $2,000. They also adopted a set of traffic regulations relating to the bridge that were to be enforced by the officers. Some of these regulations were: lingering on the platform, obstructing cable cars, failure to purchase tickets or place them in collection boxes, smoking on train cars, crossing train tracks, exceeding a five mile per hour speed limit, walking dogs, etc.

Bridge officers were paid a lower salary than their city counterparts. In an attempt to alleviate the disparity, a “Home Rule Message” (a letter of support for legislation by the affected government entity) was sent by the Trustees to the NYS Legislature. The message supported legislation that provided officers of the MBBPD pay parity with those of their counterparts in the cities. The Governor vetoed the bill on grounds that it was a local, municipal matter.

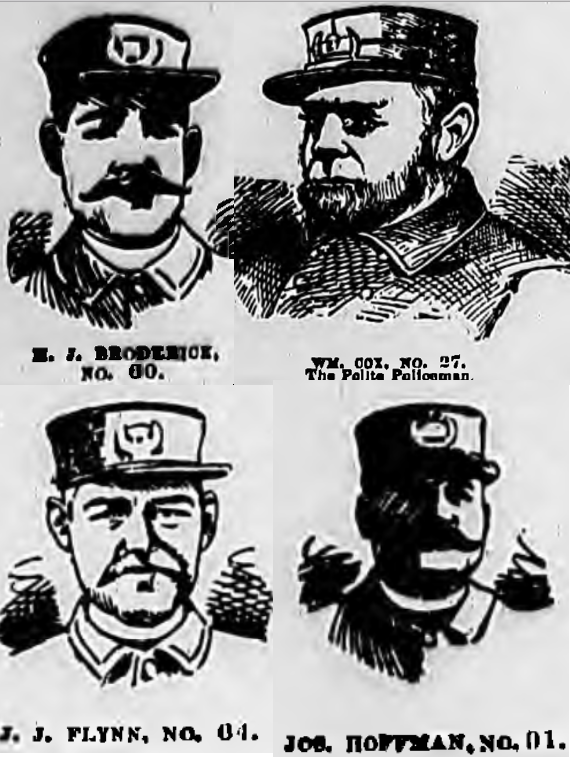

In a public relations effort to improve the reputation of the bridge force, in January 1890, The Evening World newspaper concluded a contest to identify those bridge officers who worked “faithfully and impartially.” Cash “prizes,” donated by an anonymous donor gave the paper $100 in prize money to distribute. Citizens were encouraged to write letters to the paper nominating officers. Ultimately, the prize was split among four bridge patrolmen: William Cox, N.J. Broderick, J.J. Flynn, and Joseph Hoffman.

In August 1891, bridge Ptl. Joseph Smith was arrested by a detective from PDNY Inspector Byrne’s office on an Arrest Warrant issued by the Paterson, New Jersey Police Department charging Smith with Murder. According to limited news accounts, Smith’s sister, Ms. Wells ran a boarding house in Paterson. Smith and his family were staying at the house while he was on vacation from the bridge force. Smith returned to the house after an evening of drinking and engaged in a verbal argument with his sister regarding his excessive drinking. At some point, Smith struck his sister.

Minutes later, another resident of the house, John McElbery, while passing Smith on the basement stairs, made a remark to Smith which caused Smith to hit McElbery in the jaw with a blackjack. The force broke McElbery’s jaw, rendered him unconscious and he fell down the stairs fracturing his skull at the top of his spine causing his death.

In an attempt to cover-up the crime, McElbery’s body was removed from the house and left in the street where a passerby noticed it and notified a police officer. The police quickly determined the truth and sought Smith who had “hastily gathered his family and baggage together and made a hurried departure.” No further information was disclosed.

An updated manual containing 87 Rules governing the members of the bridge force was published and adopted in June 1894. The revised regulations incorporated legislation enacted in 1894 which gave the bridge officers parity in both pay and hours worked with their counterparts in the cities.

In what was perhaps an effort to determine why the bridge officers appeared to be the subject of a disproportionate number of disciplinary, legal matters, and illness, the new rules and regulations provided that all members of the force submit themselves for a physical examination before the Police Surgeon appointed by the Trustees. The rules and regulations also called for the Chief Engineer of the bridge company to report the names of officers that were “best qualified, in his judgement, mentally, morally, and physically, to construct the police force” of the bridge.

From the time of its inception, bridge officers were appointed, promoted, disciplined and dismissed at the sole discretion of the Trustees. In May 1895, NYS Governor Roswell P. Flower (1892-1894) signed a bill which gave some protection to the officers. The bill allowed for the termination of officers only after a public hearing of the charges was held and upon a majority vote of the Trustees.

The frequent reporting on disciplinary action against the bridge officers contributed to the dismal reputation of the force. One officer in particular stood out amongst his peers as the black sheep of the force. His repeated violations of the rules and regulations, and of the penal law, which resulted in repeated disciplinary and criminal charges seemed to bounce off of him due to his ties with Tammany Hall.

“Bulletproof” Bridge Ptl. Michael Lally

Ptl. Michael Lally, is the most egregious example of all that was wrong with the bridge force and the politically appointed men that wore the uniform of the MBBPD. Lally was appointed to the bridge force on March 4, 1884 as a result of the intervention of an influential NYC Alderman named Pat Divver. Lally was a “barroom rowdy” and a Tammany committeeman of the Second Assembly District who “always delivered” his district for the Tammany-backed candidates. It was reported that Alderman Divver had attempted to have Lally appointed to the NYC Municipal Police force, but Lally “could not answer the most simple question on the civil service exam.”

Months after his appointment, while on duty, Ptl. Lally left his post and walked to a saloon located at 97 Front St., Manhattan. After drinking for some time, he pointed a revolver at a bartender’s feet and ordered him to “Dance or Die!” Ptl. Lally shot the bartender in his leg. Lally’s friends quickly ushered him back onto the bridge where he resumed patrol. The victim’s attempts to press charges were hampered by interference by Lally’s friends, fellow bridge officers, politicians, and ultimately the Trustees. The building where the saloon located at 97 Front St., was owned by a Police Justice.

Two months later, Lally was charged with assaulting a man in front of a saloon. The victim was hospitalized for several weeks, however the charges against Lally “fell through” after Lally’s “friends” intervened.

Ptl. Lally was arrested after he again left his post, this time to “visit the apartment of a respectable woman” on Pike Street. After nearly strangling the woman, Ptl. Lally was arrested for assault. Additionally, a departmental complaint by an elderly man for an unprovoked assault committed by Ptl. Lally while on duty was also lodged with Capt. Ward.

In November of 1889, Ptl. Lally was again involved in a shooting incident, this time while while off-duty, intoxicated, and in a bar. The bar “Lally & Durkin,” located in Manhattan beneath the structure of the Brooklyn Bridge, was described as “a hole of the worst description, in one of the most vicious parts of the city.” It was believed that , although Ptl. lally’s father’s name appeared on the license, the officer himself was the proprietor.

According to the article, Ptl. Lally accompanied the injured man, Peter Hurley, the bartender at Lally & Durkin, to the hospital and attempted to force his way into the operating room. When he was turned away, he displayed his bridge officer shield and demanded entry. After being rebuffed again, he handed the surgeon a $5.00 bill in an attempt to bribe his way into the room. The badly injured victim provided the doctors with a story that he had accidentally shot himself while handling a gun in front of his residence and then refused to make any statements. Hurley survived, but the bullet remained lodged in him for the rest of his life.

Capt. Ward told reporters that he interviewed Ptl. Lally who denied any knowledge of the incidents in the bar and in the hospital. It was further reported that Ptl. Lally told reporters that at the time of the incident he was in the vicinity of Front and Roosevelt Streets. Capt. Ward independently told the reporters that Lally sent a messenger to him with a note that he was too ill to report for duty and was at his residence at the time of the incident. It was understood that “Lally was trying to lie himself out of the scrape.”

Ptl. Lally remained on the force, and continued to be a public embarrassment to the force until January 1891, when he was finally dismissed from the force for assaulting a superior officer, Roundsman William Brophy. Roundsman Brophy cited Ptl. Lally for being intoxicated while on duty. Ptl. Lally then assaulted the Roundsman. Many believed that Lally would be restored to the force, but within days, another, more serious incident than those aforementioned, appeared to seal his fate.

A newspaper reported that Lally, who was intoxicated at the time of the assault against Roundsman Brophy “continued on a debauch until Sunday,” January 18. On that date, Lally entered a boarding house known as the “Old Sailor’s Home,” located at 342 Water Street, Manhattan and demanded that the bartender, John Decali, serve him a drink. When the bartended refused, citing Lally’s apparent intoxication, Lally drew a revolver, shot Decali in the stomach, and left the home.

A witness followed Lally into another saloon, Peter Foley’s, located at the corner of Front and South Streets, Manhattan, and notified a Patrolman from the Madison Street Station who arrested Smith as well as the bartender of the saloon (for violating the Excise Law, which prohibited the sale of alcohol on Sundays). Lally was brought before the victim who positively identified him as the assailant. Additionally, a coroner, believing that Decali was to die, took a statement known as a “Dying Declaration” from him, in which he once again identified Lally as the assailant.

Defendant Lally’s first appearance in a Tombs courtroom caught the attention of Lally’s political “hook,” Pat Divver, now Police Justice Divver. Soon thereafter, court reporters began to observe and report extraordinary incidents relating to the handling of the case, such as officers forgetting to advise the court of the existence of witnesses, the appearance of new witnesses with statements contradictory to the evidence, and a change in the medical report on Decali’s condition. At a hearing held soon thereafter, Decali told the judge “It was my fault Judge. I am very excitable. I struck Lally with a club, and then a stranger came into the place and shot me. It wasn’t Lally.” When pressed by the judge, Decali testified that he did not see who shot him. Decali later returned to Italy where the bullet remained lodged in his chest until he died.

Lally was so brazen and bold that he announced that he intended to apply for reinstatement to the MBBPD on the grounds that he “was not represented by counsel at his trial.” What trial he was referring to remains unclear, but the newspaper concluded the article thusly “With the ‘pull’ behind him many believe he will succeed.”

Once again, in May 1892, Michael Lally’s name would appear in newspaper headlines. The assault case against him in connection with the shooting of Decali was still open and the law at the time called for a dismissal should the case not be tried within two years. Newspapers alleged that the case was being drawn-out so that under this law, it would be dismissed. It was reported that Lally had been “tipped” and fled to the coal mine region of Pennsylvania, then to Boston where he boarded a steamer for Ireland to avoid the jurisdiction of the court.

Seven months later, with assurances from his political connections that “everything would be plain sailing,” he returned to NYC and remained free on bail.

In a broader view of the state of affairs of the MBBPD, after Lally’s dismissal, a newspaper wrote ”No one knows why the Brooklyn Bridge police discipline should breed the extraordinary creatures found upon the force, but now that the recent dismissed Bridge bully, Michael Lally, has put a bullet through a man, with doubtless fatal results, possibly Superintendent Martin will take hold of the membership, weed out the ruffians and encourage those who are civil and obliging, as well as those politically ‘influential.’”

In what appears to be ex-Patrolman Lally’s last encounter with the law, Lally was arrested in December 1893 pursuant to an indictment by a New York County Grand Jury for illegal Electioneering in connection with the re-election of Police Justice Patrick Divver.

Bridge Jumpers

From the time the bridge was built, threats regarding individuals who sought to jump from the bridge were a cause for vigilance by the bridge officers and a source of frustration to Capt. Ward and the Trustees. The novelty of surviving a bridge jump would lead to notoriety for the jumper and the potential for financial gain from the publicity. Of course, others jumped to end their lives.

In 1885, Robert Odlum, the first known jumper, died as a result of his jump.

The first claim by anyone to have jumped, and survived, from the bridge belonged to Steve Brodie, of Manhattan, who claimed that on July 23, 1886 he jumped from a height of 135 feet. Brodie’s claims were supported by only two friends who claimed that they were in a boat on the East River awaiting his jump. Additionally, a bridge officer, Ptl. Michael Lally, reportedly ran to the rails of the bridge, looked down, and observed Brodie climbing out of the water and into the boat. On shore another Patrolman came upon Brodie when the boat arrived on shore. The officer reported that Broidie was intoxicated, his clothes were wet, and promptly arrested him.

Newspapers bought into his account and Brodie leveraged his fame to the maximum for his financial gain. Brodie’s saloon, “Steve Brodie’s,” located at 114 Bowery, was an attraction for residents and tourists. The saloon was decorated with newspaper headlines, articles of clothing, artifacts, etc. relating to Brodie’s purported jump. It was reported that at the time of his death, Brodie’s estate was worth over $80,000.

The following month, on August 28, 1886, the bridge force was on the lookout for Charles E. Bishop who had announced to the world that he intended to be the second person to jump from the bridge and survive. While they did not encounter Bishop, they did encounter another jumper.

Ptl. James Fitzgibbon was on duty when a trolley car conductor notified him that a man had jumped from the bridge. Ptl. Fitzgibbon reported that he observed a man in the river, swam to a nearby row boat, and made it to the nearby docks, where he was promptly arrested.

The jumper was identified as Lawrence M. Donovan, of 58 New Chambers St., Brooklyn, a 24 year old printer employed by the Police Gazette, a periodical relating to police news. While Donovan would not confirm it, the best information at the time was that the Police Gazette made the bet. Donovan told authorities that he jumped to fulfill his side of a $500 bet. The proof of Donovan’s jump is much stronger than that of Brodie’s and he certainly may have been entitled to hold the title of the “first” person to survive a jump from the bridge.

To attempt to dissuade future jumpers “life lines” (metal cables) had been installed along the bridge, however these were not effective. In October 1886, the bridge Trustees connected the life lines to the electrical circuit that illuminated the lights on the bridge. “As a member of the force put it, the first man, woman or child that touches them will have to be taken to the hospital.” How long it was before the Trustees let the electric fence remain, or if anyone was electrocuted is not known at this time.

In August 1896, the first woman to attempt to jump off of the bridge for the purpose of gaining notoriety and money was Mrs. Clara McArthur of 162 E. 127th Street, Manhattan. At 5:30 am, accompanied by her husband John, and her five year old son, they put their plan into action. The McArthurs arranged for a boat to be present in the river and for “plenty of witnesses” to be present at the scene. Unfortunately for the

McArthurs, someone had tipped off the bridge police who were waiting for the McArthurs’ arrival. McArthur abandoned her plans.

Preparedness for Terrorism

The Spanish-American War (1898) was underway and the United States military was engaged in combat in Cuba and the Philippines, where those countries were fighting for independence from the colonial control of Spain. America’s intervention in Spain’s affairs caused the country to fear reprisal, in the form of violence or terrorism, from Spanish agents and supporters.

The NYC police department feared that agents of Spain may attempt to disrupt the water supply or blow up the Brooklyn Bridge. The department detailed men to the water system and to assist the MBBPD in the vigilance of the bridge. This may be the first instance noted in the history of the NYC police department, relating to the department’s awareness of the potential for a terrorist attack against the NYC water supply or a bridge (The Brooklyn Bridge was the only bridge at the time).

In the early 1890s, NYC officials began to discuss the concept of expanding NYC beyond the coterminous shores of Manhattan Island. Already, in 1874, NYC police had taken over the duties of policing the towns and villages of Westchester County (Westchester included the area of today’s Bronx in the era) that were west of the Bronx River. As new, faster, reliable modes of transportation were entering the scene, the far off, rural, undeveloped extents of what are today’s five boroughs beckoned for development and did not seem to be so far away. The results of much public debate, lobbying, political machinations, and legislation resulted in The Greater New York Charter of 1897 (the Charter). [Note: There were many revisions to the charter and laws pertaining to the consolidation. For the purposes of this article, this one was selected.]

In the end, on January 1, 1898, the MBBPD and eighteen other police departments joined the NYC force.

A chapter of the Charter (§314 entitled “Detail of Officers and Men to Assist the Department of Bridges”) set forth that the Commissioner of Bridges was empowered to request from the NYC police department a detail of men to enforce ordinances and regulate travel over the bridges of the city; that these men were to be employees of the city police force and paid from city funds; and that the Commissioner of Bridges may recommend to the NYC police department, for disciplinary action or replacement, the names of any officers whom he saw fit.

Section 278 of the Charter provided, pursuant to §8 Ch. 300 of the Laws of 1875, for the transfer of the members of the bridge force to the NYC force. On December 31, 1897 the bridge force consisted of one Captain, three Sergeants, three Roundsmen, and 95 Patrolmen with expenses for 1897 of $103,688 compared to $2.3 million for the City of Brooklyn PD, and $7 million for the PDNY.

On January 1, 1898, the day that the consolidation act took effect, the bridge force of 97 men were enumerated into the number of the PDNY. In effect, the men became NYC police officers and retained their ranks. In his first report as Chief of Police of the Police Department of the City of New York, John McCullough reported that of the 97 men of the old bridge force, seven were “disabled either from old age or physical disability.” Chief McCullough recommended that their individual cases face a final determination. The body of police officers who worked out of the “Bridge Precinct” was referred to as the “Bridge Squad.”

While it is not known when the Bridge Police Headquarters was relocated, by 1898 it was located at 179 Washington St. Regarding the MBBPD headquarters, Chief McCullough determined that “The place is entirely unfit for station house purposes” and that a suitable location needed to be found as soon as possible. He concluded his report on the bridge force’s consolidation by stating that he recommended that, once a new precinct station-house be found, that it be manned by four Sergeants and four Roundsmen.”

On May 1, 1898, many precincts were renumbered (re-designated) including the “Bridge Precinct,” which was re-designated the “Fourth Precinct.” The “precinct” remained in the basement of the 179 Washington St. building, however, due to its poor condition, it was used only as a muster-room (to turn out the men). The Annual Report of the Police department of New York for the Year Ending 1898 indicates the location of the 4th Precinct as “Brooklyn Bridge.” The report also indicated that the 4th Precinct “is a basement floor in the Executive building of the NYBB, lending further credence to the fact that the police officers were located at, near the Brooklyn terminus.

By October 1903, the PDNY had reassessed the manpower needed to police the bridge. The installation of a telephone system by which officers stationed along the roadways leading to and along the bridge, facilitated communication and was one of the reasons cited for reducing the number of officers. The roadways leading up to the bridge were called “the loops” and required 24 traffic officers. The near 100 men that of the old MBBPD that were required to police the bridge was reduced to sixty.

Summary

What’s the deal with the history of the Manhattan & Brooklyn Bridge Police Department? The MBBPD was legislated into existence years before the 1883 opening of the bridge. Initially officers were to be detailed from the existing police department that covered the cities of New York and Brooklyn. Ultimately, the Trustees of the bridge company gained total control over the newly created force.

The men selected by the Trustees were below the standard of their counterparts in the cities and officers of the cities’ police departments and the public were critical of the force from its inception. Time would prove the critics to have been correct. While it was not the case for every officer, the force had a reputation as being a band of ruffians, with disproportionate levels of discipline and criminal complaints. Tammany Hall’s political influence governed the force and Tammany intervened in the outcomes of disciplinary and criminal cases against bridge officers.

Apparently there was no merit system in the department and no acts of heroism which were disclosed during this research. Policing the bridge was difficult and dangerous due to the exposure to the elements and the number of pedestrians, vehicles and trolley cars passing over the bridge. Arrests typically were alcohol-related and were of a magnitude of an average of three arrests per officer per year.

In 1898, the MBBPD was one of the 18 departments consolidated into the PDNY. The officers retained their rank and were absorbed into the PDNY. The MBBPD existed from May 1883 to midnight on December 31, 1897. While the history of the force was not stellar or extraordinary, it nonetheless is part of the history of todays Police Department of the City of New York.

Postscript 1: The research and writing of the history of policing in NYC is difficult, and those who have a passion for the same do their best to provide accurate information. New sources of information are continually being identified. If any new information is found on this photo, this article will be updated.

Postscript 2: As is the case with all of our articles, comments, input, and constructive criticism are welcome. All of the facts presented in all of our well-researched articles are backed up by documented sources and citations are available upon request.

Postscript 3: If anyone has any articles (shields, photos, cap devices, caps, helmets, etc. relating to the MBBPD and would like to have images added to this post, please contact the author!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.