Background

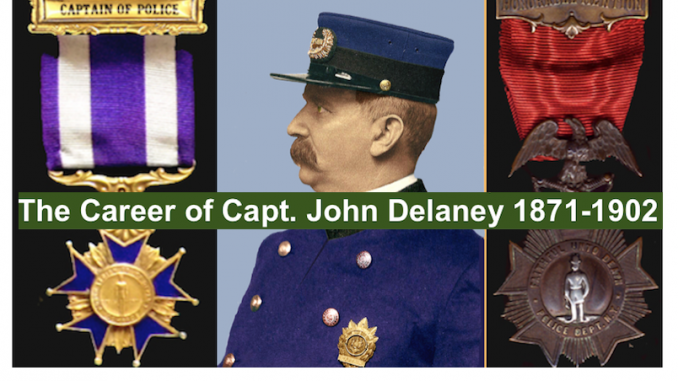

Few officers who served in the Police Department of the City of New York (PDNY) during the last quarter of the 19th century earned as many Honorable Mention recognitions and medals as John Delaney. John Delaney’s bravery, heroism and grit were demonstrated throughout the span of his 31 year career (1871-1902). This era in New York City (NYC) was a period of upheaval, steeped in graft, corruption and political influence that extended into the PDNY.

Like many of his contemporaries, Delaney’s record of bravery and heroism was contrasted by disciplinary actions that resulted in the loss of pay (fines), and allegations of blatant and systemic graft and corruption. Rather than focusing on the latter (as was the case in the preceding biography of Maximillian F. Schmittberger on this site), this biography will focus on the several acts of valor and heroism performed by Delaney which were, and remain, remarkable.

During his career, Delaney received a total of five Honorable Mentions (HM) two of which are believed to have been accompanied with a Medal of Honor (also known as “the Department Medal,” or “Department Medal of Honor”). One HM was followed by a medal from the United States Lifesaving Association.

The following is a list of Capt. Delaney’s record of Honorable Mention:

#1- September 19, 1876 – Arrest of an escaped convict

#2 – March 25, 1879 – Stopped a runaway team of horses

#3- December 23, 1879 – Rescued a drowning boy from drowning in the East River at 33rd St.

#4- March 12, 1888 – Shot and killed McGowan who shot Delaney in the eye (May 31, 1888 HM Medal first issued, to 100 men)

#5- March 21, 1902 – Honorable Mention with Medal – Fire rescue, Park Avenue Hotel Fire

About Honorable Mentions & Medals

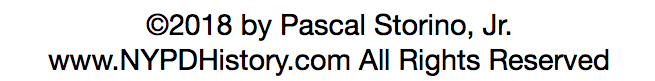

Before proceeding, it is important to understand the system of recognition in the era. Between 1871 and 1883, the only recognition for acts of valor was HM (simply a written recognition in the records of the department) or a 1871 style Medal of Valor. In 1879, two additional (higher) orders of HM were added. The first was called “Highly Honorable Mention” (HHM) which was a HM accompanied by a certificate (below). The second was HHM with Medal (the 1871 medal). The addition of the certificate and/or medal appears to have been made on a case-by-case basis before it became a matter of practice. The Department Medal of Honor was first issued in May 1888.

[Note: To learn more about the the PDNY’s the Department Medal of Honor, click here.]

Early Years of Career; Honorable Mentions 1 & 2

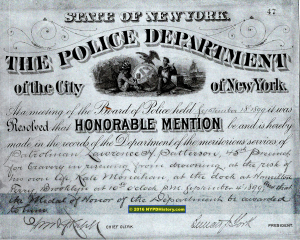

According to the records of the PDNY, the Irish-born (1849) John Delaney was appointed as a Patrolman (Ptl.) on November 15, 1871.

In 1876, Ptl. Delaney, earned his first HM for the arrest of an escaped convict. It was customary in the period, at the discretion of the Board of Police Commissioners, that officers who received HM could be further rewarded by promotion.

As a result of his having earned the HM, in 1877, Ptl. Delaney, was promoted to the rank of Roundsman (“Rnds.” was the official abbreviation for the rank) (equivalent of today’s rank of Sergeant).

According to the primary records of the city government, in January 1879, Captain Michael J. Murphy, recommended to the Committee on Rules & Discipline that Rnds. Delaney receive recognition for “meritorious conduct.” Delaney, who resided at 759 Second Ave., received a second HM for stopping a runaway team of horses which resulted in saving the lives of a number of pedestrians in the team’s path.

In this context, “runaway” was a term used to describe a horse, or horse

drawn vehicle, that was out of human control and running in a manner that had the potential of causing injury or death to humans. In the era, runaways were a major danger and the frequent cause of injuries and deaths. Officers were often cited for stopping runaway horses and many lost their lives while attempting to do so.

Honorable Mention 3 & U.S. Life-Saving Association Silver Medal

Rnds. Delaney’s third act also resulted in his being presented with an HM and a Silver Medal by the U.S. Life-Saving Service. According to accounts of the incident, Rnds. Delaney was making his rounds near the East River at 33rd St. when the cries of “Boy overboard!” called out by the passengers of a passing paddle-boat on the river caught his attention. Rnds. Delaney ran to the bank of the river where he was told that a young boy, George McFadden, age seven, had fallen from a moored canal boat due to the wake of the passing paddle boat. The flood tide current and wake swept the boy under the canal boat.

After quickly assessing the situation, Rnds. Delaney unmoored one canal boat and called out to the captain of another to unloose his boat as well. When the boy’s lifeless body came to the surface, Rnds. Delaney, fully clothed, jumped into the river, swam to the boy, and brought him to the side of the paddle boat where they were both raised onto the deck. After “considerable effort” to resuscitate the boy, he regained consciousness and was returned to his parents.

As a result of his heroic efforts, Rnds. Delaney’s health deteriorated. Suffering from a persistent pulmonary condition, Police Surgeons deemed him unfit for full duty and he was detailed to the First Court Squad at the Tombs Police Court while he recovered. As was the case with Delaney’s earlier promotion to Roundsman, as a result of his second HM, Rnds. Delaney was promoted to the rank of Acting-Sergeant. The rank of Sergeant (Sgt.) was equivalent to today’s rank of Lieutenant.

Honorable Mention 4 – A Near Death Experience

As has always been the case with police work, no assignment is entirely safe, and while the department’s assignment of Acting-Sgt. Delaney to the Court Squad was well intentioned, Acting-Sgt. Delaney’s life would be changed forever on January 2, 1883. Court Squads assisted Police Justices and served essentially the same duties as court officers do today, with additional duties of police work as detailed by the justices.

An account published on January 3, 1883, in the New York Times, related the story of Actg.-Sgt. Delaney’s harrowing incident the day earlier. According to the article, and other sources, Actg. Sgt. Delaney, “an invalid,” was assigned by Police Justice Power to serve a warrant for the arrest of the bartender of a “low groggery” named “McGlory’s Old Armory Hall,” located at 144 Hester St. The saloon was owned by Andy Kelly, and operated under the license of Mike Ryan, due to the fact that Kelly was ineligible to hold a license.

The warrant was issued after the Justice Power heard the testimony and complaint of James Nolan, a farmer from Danbury, Connecticut, who related that a bartender had “pocketed” a $20 bill from Nolan when he purchased a beer at McGlory’s saloon. Actg.-Sgt. Delaney, dressed in civilian clothes, accompanied Nolan to the bar and planned to arrest the bartender, if present and if Nolan identified him as the culprit.

Present in the bar were Patrick McGowan and his mistress, Tilly Cavanaugh. Both were highly intoxicated. Delaney, Nolan, and an acquaintance of Nolan’s, Albert Kessler, had a drink at the bar while Nolan looked for the bartender that had stolen his money.

The bartender on duty, James Cooney, recognized Delaney as a police officer and whispered the same to McGowan who hurled curses and insults at Delaney and told Delaney to bring his friends upstairs. Delaney identified himself as a police officer to both Cooney and McGowan and told them that he had a warrant for a man that he suspected as being present in the five story tenement. Frightened by McGowan’s words, Nolan left the premises, leaving Delaney and Kessler to fend for themselves.

As Delaney began to ascend a staircase, Cooney grabbed hold of him and McGowan. McGowan violently struck Delaney on the head with the butt of a revolver. According to a newspaper account, at this point Delaney “exclaimed that he was being murdered” causing Kessler to run to the Elizabeth St. Station-house for assistance. McGowan continued to beat Delaney, who was in a nearly indefensible condition, and then with his pistol in hand ran outside where his mistress, Tilly, had hailed a hack (cab). McGowan began to enter the hack when Actg.-Sgt. Delaney appeared at the tenement house door. McGowan drew his revolver and pointed it at Delaney who stepped back into the vestibule and drew his revolver. McGowan re-entered the coach and ordered the driver to flee.

Actg.-Sgt. Delaney ran to the horses, took hold of their reins, identified himself as a police officer, and ordered the driver to halt. McGowan again ordered the driver to flee and the driver whipped the horses. While walking backwards towards Elizabeth St., holding the reins in one hand and his revolver in the other, Delaney saw McGowan raise his pistol and aim it at him. Both men fired simultaneously. Delaney fired at least twice, striking McGowan. Ms. Tilly watched as McGowan slumped into the floor of the carriage as he exclaimed “Oh! My God! I’m dying.” Ms. Tilly fled the hack and hid in a nearby building. Patrolmen Farrington and McCoy arrived at the scene and took McGowan to the 6th Precinct Station-house, located at 19 Elizabeth St. where he died on the floor of the sitting room.

Other officers carried Actg. Sgt. Delaney to the same station-house. According to the the New York Times article, although he suffered from a gunshot wound to his eye and was bleeding profusely, Actg.-Sgt. Delaney, upon seeing McGowan’s lifeless body on the floor, said to the precinct captain “Captain, that’s the man who shot me, and I shot him. I did not intend to use my pistol, but I had to do it.”

Doctors reported that the bullet passed though Delaney’s upper right eyelid, passed through his eyeball, and lodged in his right cheek near his brain. Doctors removed the eyeball and feared that Delaney may die due to a hemorrhage to the brain as a result of inflammation.

As was the practice in the period, a Coroner’s Inquest was held after the coroner performed an autopsy of McGowan’s body. The witnesses testified and were then sent to the House of Detention where they were held as material witnesses. At the conclusion of the inquest, on January 4, 1883, the jury took ten minutes to render a verdict of justifiable homicide and the witnesses were released.

On March 23, 1883, Actg.-Sgt. Delaney was awarded his fourth HM in connection with the McGowan incident. To date, research remains inconclusive that Delaney was awarded a medal in connection with this HM. However the evidence strongly suggests that he received a Department Medal of Honor.

In February 1884, after a long period of recovery, Delaney was promoted to the rank of Sergeant.

The Department Medal of Honor Medal was first issued (to 100 men) on May 31, 1888. The 100 men were presented with medals for acts performed in previous years. A newspaper article, published in April 1888, reported that “the new medals of honor to be presented to all members of the force who have received honorable mention by the Police Commissioners are expected to be ready for distribution in time to be worn by the recipients at the coming parade of the force on May 31,” 1888.

Bartender Cooney and the hack driver, were held for trial in June 1883 to answer charges relating to their obstruction of police officer Delaney during his attempted arrest of McGowan. In February 1884, after a long period of recovery, Delaney was promoted to the rank of Sergeant.

In November 1886, Sgt. Delaney, assigned to the Broadway Squad, was awarded $1,000 by the Board of Trustees of the Riot Relief Fund to aid him with his injury and recovery. The Riot Relief Fund was established on July 17, 1863, by Henry J. Raymond, Paul S. Forbes, and Leonard Jerome, at Delmonico’s Restaurant to “afford measures of relief to the families of policemen, firemen and militiamen killed in the Draft Riots” of July 1863. Before 1886, the purpose of the fund was expanded to include policemen injured in the line of duty.

In 1892, Sgt. Delaney (again assigned to the Tombs Court Squad) was promoted to the rank of Captain.

The Juxtaposition of Delaney’s Valor and Heroism to Graft & Corruption

In light of widespread allegations of graft and corruption within the PDNY, Republican State Senator Clarence Lexow was appointed Chairman of a new committee formed to conduct an “Investigation of the Police Department of the City of New York.” The Lexow committee met from February to December 1894. Hearings, spearheaded by the committee’s Chief Counsel, John W. Goff, Esq., began on March 9, 1894. During the committee’s 74 sessions almost 700 witnesses provided testimony that resulted in the January 8, 1895 transmittal of the committee’s 10,576 page report to the NYS Legislature.

In December 1894, Capt. Delaney was called before the committee and provided testimony regarding the circumstances of his apparent wealth beyond his means which included several houses. In sum and substance, Capt. Delaney testified that his recently deceased wife had, before their marriage, inherited a large sum of money from her father; that she invested the money by purchasing homes which she titled in her brother’s name; and that he was unaware of her investments.

So incredulous were his explanations that Prosecutor Goff said “Captain Delaney, out of mercy to you I will let you go. I don’t think you are in your right mind. I think that the injury on your brain you have received…really affected your mind.” Capt. Delaney was “off the hook” with the Lexow Committee, however, soon hereafter charges of incompetence were made against him by a minister, and Capt. Delaney was subjected to at least six punitive transfers in command from one precinct to another.

Not even rank, longevity on the force (31 years), or the repeated infliction of severe injury could separate Delaney from performing acts of heroism. As hair-raising and harrowing the acts of heroism performed by Capt. Delaney to date were, his five prior HMs were “Honorable Mention” (Certificate only) and were not of the highest order “Honorable Mention with Medal.” That would change after February 22, 1902.

Honorable Mention 5, with Medal; The Park Avenue Hotel Fire

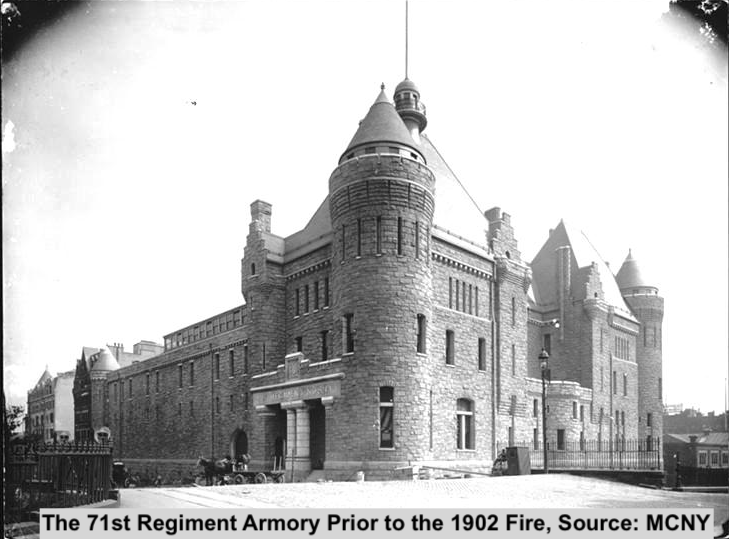

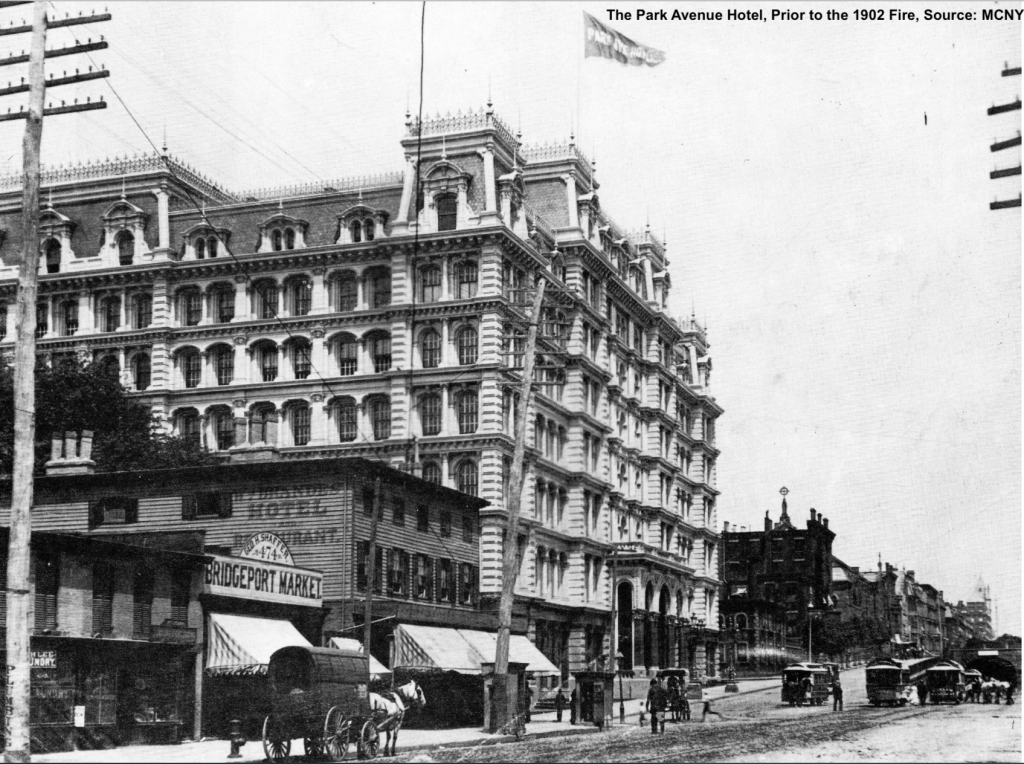

On the cold, stormy winter night of February 22, 1902, Capt. Delaney, of the East 35th St. Station-house, was present at the scene of a fire at the 71st Regiment Armory, which was located on the east side of Park Avenue at 33rd St. High winds caused the fire to spread throughout the interior of the building. Fire Chief Edward F. Croker was not concerned about dying embers due to the fact that the rooftops of building were snow covered. However, large embers flew into the air and landed in the elevator shaft of the 10 story Park Avenue Hotel, located across the street.

According to newspaper accounts, a battalion chief of the fire department noted that hotel employees were out on the street watching the 71st Regiment Armory fire; that he saw a light coming from the hotel’s elevator shafts; that he ran to the hotel and saw that there was a fire in the shaft way; and that the flames were spreading quickly to the upper floors. Finding no fire apparatus to work the fire, he began to rouse the occupants.

Capt. Delaney also saw the light emanating from the elevator shaft and ran into the hotel. On the upper floors he found an elderly man who was in danger of succumbing to the smoke. Capt. Delaney directed the man to the stairwell. Other policemen under his direction located and evacuated hotel guests.

Captain Delaney is reported to have given the following account “Everybody was asleep…when I entered the hotel. With such men as I could spare I went to the hotel and made the rounds of the upper floors. The people were fast asleep, and we had to drag some of them from their beds. The article continued and noted that Delaney said that “pandemonium reigned among the employees;” that in a rush to escape, the employees abandoned the guests; and that “credit is due to Captain Delaney for the prompt action in meeting the crisis. He was the first man to ascend the stairways, and no less than eight persons were saved from death in the flames as the result of his perilous tour. His disposition of policemen later served to avert panic, and his men did valiant service in assisting the injured.”

Deputy Police Commissioner Thurston, on behalf of Police Commissioner (PC) John N. Partridge (1902-1903), was quick to praise Capt. Delaney and his men for the “splendid character of the duty performed under the most disadvantageous circumstances” during the fire.

On March 22, 1902, PC Partridge ordered “That Honorable Mention be and is hereby made in the records of the Department of Captain John Delaney, Roundsman William A. Miles,” and eleven patrolmen “for heroic conduct on rescuing a number of persons from the Park Avenue Hotel fire…and that the Medal of Honor of the Department be and is hereby awarded to each of said officers.”

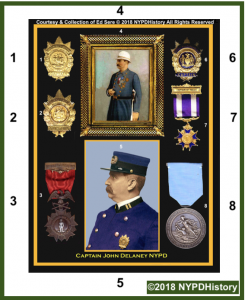

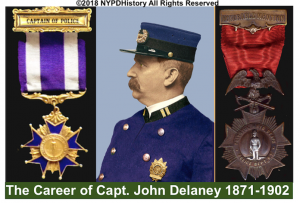

The items depicted in the above image are as follows:

- Capt. Delaney’s 1871 “First Issue” Municipal Police Captain’s Shield

- 1894 – 14k Solid Gold Municipal Police Captain Shield – Presented to Capt. Delaney as a “gift from a friend”

- Capt. Delaney’s Department Medal of Honor

- Circa 1898 – A hand tinted (colorized) image of Capt. Delaney wearing medals.

- (Note: The white helmet was worn by officers on the occasion of the 1898 Police (Consolidation) Parade) and is correct.)

- A colorized, circa 1898, photograph of Capt. Delaney wearing Consolidation Era brass buttons and a City of New York Police Captain Shield, 1898 (Post-Consolidation)

- A City of New York Police Captain Shield, 1898 (Post-Consolidation)

- A “Membership Badge” (the proper term) of the Honor Legion of the Police Department of the City of New York

- (Note – Officers who received Honorable Mention with, or without medal, were eligible for membership in the fraternal organization that was/is the Honor Legion.)

- The Silver Medal of the U.S. Life-Saving Association

Within eight months, on October 16, 1902, Capt. Delaney stood trial on departmental charges. The charge was that, while serving as the commanding officer of the East 35th St. Station-house, he failed to close a poolroom located in the Sherman Hotel, 156 East 42nd St., Manhattan. PC Partridge served as the final arbiter.

The charges were filed by Inspector Nicholas Brooks after county detectives on the staff of District Attorney (DA) William Travers Jerome executed a raid on the premises. During the raid, one of DA Jerome’s men shot a fleeing man in the head as the man attempted to escape over the rooftops.

General (Genl.) Benjamin F. Tracy, Esq. served as defense counsel for Capt. Delaney. During his opening remarks, Genl. Tracy cited Capt. Delaney’s 30 years of service and sacrifice to the department. Genl. Tracy stated that in his review of the case, he was impressed “very strongly with the fact that this officer has been suffering from that injury (gunshot to brain), and that the injury is progressing and has been growing worse and worse for the last two or three years.” Genl. Tracy concluded his opening remarks by stating that it was his conclusion that “this officer is not physically competent or capable to discharge the very onerous duties (of police work)…and that his (Delaney’s) interests and the interests of the department” will soon prompt Delaney’s retirement.

Genl. Tracy asked PC Partridge to appoint a board to examine the “physical and mental competency of Captain Delaney.” The case was adjourned and on October 31, 1902 Capt. Delaney was retired from the department.

The Citizens Union, a NYC “watchdog” and advocacy group, that remains in existence today, included Capt. John Delaney on a 1903 list of “transgressors” that retired in lieu of having their records examined “under the microscope.”

John Delaney died sometime prior to February 1913. In researching this article, a senior researcher with NYPDHistory.com contacted one of Capt. Delaney’s relatives. The gentleman stated that the only information the family had relating to Capt. Delaney’s death, was that he was struck and killed by a brewery truck and that Delaney’s body is believed to have been buried in Calgary Cemetery, Queens, NYC.

Reputation Beyond Death; Curran Commission Testimony Implicates Delaney

In 1913, newspaper accounts reported the testimony of James Purcell, the partner in crime of Herman Rosenthal, a large-scale, well-known racketeer of the era. Rosenthal was murdered on the day that he was scheduled to appear before a grand jury empaneled by DA Jerome. PDNY Lieutenant Charles Becker was charged with ordering Rosenthal’s murder to prevent Rosenthal from implicating him in connection with graft and corruption. Becker stood trial, was convicted of the crime, and executed in Sing-Sing Prison’s (Ossining, NY) electric chair.

Purcell’s testimony before the Curran Investigating Committee, led by NYC Alderman Henry H. Curran, exposed ties between racketeers and police officers. Regarding Capt. Delaney, Purcell testified that in 1897, he first began paying “protection money” of $50 per week to Capt. Delaney, and $10 to Delaney’s “bagman” in return for the protection of his illegal gambling enterprises from police raids. Purcell, and other witnesses, implicated several other police officers.

Conclusion

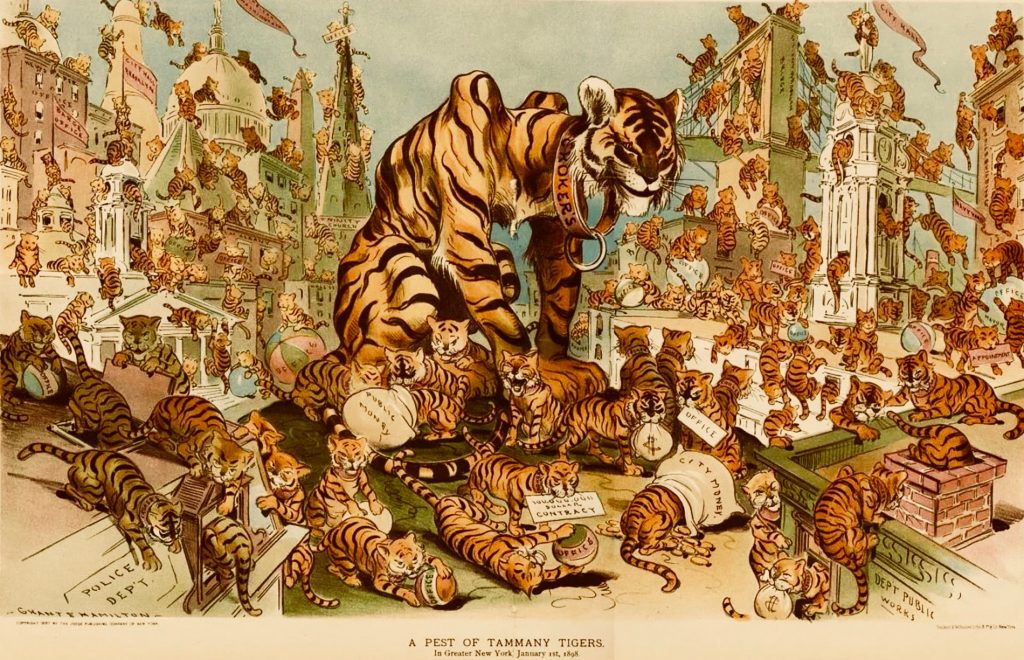

What’s the deal with the distinguished career of Captain John Delaney? As was the case with nearly all officers who rose through the ranks to Captain, Inspector, or higher, in the last quarter of the 19th century, the claws of the “Tammany Tiger” took their hold on the officers and compromised their integrity.

Tammany Hall was the Democrat Party’s political machine. Tammany used the PDNY as a tool to extract as much money through graft and corruption as possible. During his career, it was well-known that Delaney was a “Tammany Man” and that he lived by the maxim “to the victor go the spoils.” During the mayoralties of Tammany-backed mayors, Delaney rode high. Under “Republican,” “Reform,” or “Fusion” party-backed mayors, Delaney suffered frequent punitive transfers and had to answer allegations lodged against him.

While allegations against Delaney were made throughout his career, the allegations brought forth by the Lexow Committee (1894) and Delaney’s dubious testimony were not the only allegations made against him during his career. The testimony during the Curran Commission (1913) certainly echoed earlier allegations. If not for Capt. Delaney’s record of heroism and valor – and the bullet lodged in his brain (twice cited as an excuse for leniency) – the outcome of each investigation many have had different results.

What distinguished Capt. Delaney from the vast majority of other officers during this period in the history of policing New York City were his acts of heroism and valor. Many of his contemporaries rose through the ranks, were involved in graft and corruption, suffered the consequences, and had not performed an act(s) worthy of recognition.

After the Medal of Honor was first issued in 1888, it was not uncommon for officers to receive HM with medals for nearly the identical acts of valor and heroism for which Delaney received his HMs. If he had been awarded a medal for each of his five acts he would have been presented with one medal and four additional hanger bars, one for each subsequent act. The following is an artist’s rendition of what the medal would have looked like.

I would like to thank Mr. Ed Sere for sharing images of his collection and for his continued support, guidance, and friendship. In sharing images of his collection, here and in other articles on this site, he has permitted NYPDHistory to share the history of New York’s Finest with the world!

Postscript 1: The research and writing of the history of policing in NYC is difficult, and those who have a passion for the same do their best to provide accurate information. New sources of information are continually being identified. If any new information comes to light this article will be updated.

Postscript 2: As is the case with all of our articles, comments, input, and constructive criticism are welcome. All of the facts presented in all of our well-researched articles are backed up by documented sources and citations which are available upon request.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.