![]()

Chapter 1: “What’s the Deal With:” Tammany Hall’s Corruption of the New York City Police Department?

Introduction:

The study of the history of policing in New York City reflects the broader history of the city and the nation. The evolution of policing from the time of the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam to the multi-borough Police Department of the City of Greater New York (NYPD) has been written about by a wide spectrum of authors. These authors come from various backgrounds, have both objective and subjective perspectives, and publish in formats ranging from social media to websites and books.

The influence of Tammany Hall in the development of New York City and its police department remains unchallenged by historians. The history of the city, and its police, cannot be told without including Tammany. Tammany’s actions permeated nearly every socio-economic, demographic, geo-political, etc. aspect of life in and around the city, throughout New York State, and in other cities and states. The systemic police corruption endemic from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries were the result of Tammany’s corrupt influences and did not emanate from within the department.

In light of the present federal corruption investigation(s) into the government of New York City, and the New York Police Department (NYPD), those familiar with the history of the city may see the opportunity to compare and contrast the politics, influence and corruption of Tammany with the present politics, influence, and corruption of the city’s government and the police.

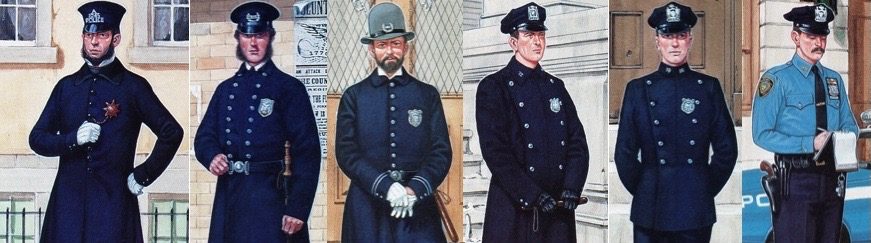

The history of policing in the City of New York began in the early 17th century, when the Dutch government created a system where individuals were responsible for enforcing the laws, bringing individuals before justices for trial, deciding innocence or guilt, and determining punishments. The system of policing developed over the centuries into the department we know today, commonly referred to as the New York City Police Department (NYPD). Whether the organization was called “The City Watch,” “Day and Night Police,” “The Police Office,” “The Metropolitan Police District,” “The Municipal Police Department,” “The City of Brooklyn Police and Excise Department,” all of the men (and later women) who gave their lives in the performance of their duties are recognized by today’s NYPD, and these entities are all part of the history of the NYPD.

While reading the M.R. Werner’s 1928 book, entitled Tammany Hall, the maxim that history forgotten is bound to repeat itself came to mind. The similarities between Tammany Hall’s corruption of the NYPD and the recent police scandal(s) rocking the nation’s largest police department support the maxim.

Before proceeding to compare and contrast the corrupt institution that was Tammany Hall with the institution(s) that have corrupted today’s police department, a basis for the comparison must be framed by explaining Tammany’s historical role and how its precedent setting corruption is being repeated today on a much smaller scale. Curiously, and ironically, handguns are a common theme and their role, then and now, will answer many questions about gun control.

Chapter 1: A Primer on Tammany Hall:

“Tammany” was the vernacular name for “The Society of St. Tammany, or Columbian Order.” The Order was founded in 1786 as the Tammany Society and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the The Society of St. Tammany, or Columbian Order, Inc. William Mooney is credited with advancing the formal organization of the society shortly after the conclusion of a parade, on July 23, 1788, which was held to celebrate the ratification of the Constitution of the United States. Mooney, an upholsterer and Revolutionary War soldier, was extremely patriotic and sought to create an order that the common man could enjoy. Such men were excluded from a similar post-war social organization known as the “Society of the Cincinnati,” which was formed by the soldiers from the upper class, and ranking officers. The membership and benefits of the Society of Cincinnati were/are passed down through families to the eldest sons of each generation. The Society of Cincinnati was not named for the Ohio city, but for a 5th century B.C. statesman and aristocrat regarded as a model of civic virtue, named Cincinnatus.

The greatest of all Native American Chiefs in the Lenni-Lenape (Delaware Valley) area was named Tammany. His life, discoveries, battles and deeds were legendary. Circa 1698, Chief Tammany met William Penn and offered him a large piece of land for farming, which today is (generally speaking) geographically formed by the State of Pennsylvania. Around the time of the American Revolution the Sons of Liberty (the Revolutionaries), in a continuing effort to disassociate themselves from the British Monarchy and the Church of England, sought to create a Saint that was 100% American. Native-born Chief Tammany was thought to be a candidate to fill such a unique role.

During the Revolutionary War, the Pennsylvanian troops under General Washington’s command, chose the then “Saint Tammany” as their Patron Saint. On May 12, from 1773 and 1789, inclusive, “Saint Tammany Day” was celebrated with great fanfare to rival that of even the July 4th celebrations, which was also celebrated by Tammany members. Members dressed as “Indians” with painted faces and costumes marched in both parades throughout the colonies. In New York City, the parade terminated at City Hall where, annually, effigies of Benedict Arnold were burned.

During the Revolutionary War, General Washington effectively used the Society to mediate disputes with Indian tribes and to recruit support for the Revolutionary Army. After the War, the Society became the focal point for the “struggle for supremacy” between the aristocrats, known as “Federalists” (later led by Alexander Hamilton), and the democratic “Republicans” (sometimes referred to as the “Jeffersonians” after Thomas Jefferson). Citizens supportive of the British during the revolution were known as “Tories,” and were banned from holding public office after the Revolution. President Washington later pardoned these men and they joined the class of Federalists, which further alienated the class of men belonging to the democratic Republican class of Tammanies.

Poems, songs, and at least one play were written about Saint Tammany and were recited and sung for centuries in speeches and at Tammany societal gatherings. As an example, a famous Tammany dinner toast was “May the industry of the Beaver, the Frugality of the Ant, and the constancy of the Dove perpetually distinguish the Sons of St. Tammany.”

The members of the Society, which was limited to only “Native” Americans (used at the time to describe men born on American soil) were, at the exclusion of the Irish born immigrants who would later control Tammany for decades and were divided into the titles/positions of “Sachems,” “Warriors” and “Hunters.” There were thirteen leaders (also called Sachems), one for each tribe of Tammany, representing each of the original thirteen states. A Grand Sachem was at their head, and William Mooney was the first to hold that title. The early Presidents of the United States were given the title “Great Grand Sachem.” The titles of other officers in each Sachem took other “Indian-related” names for each office.

During the post Revolutionary War period, there were sporadic Indian “uprisings” in the thirteen Colonies, mainly over land border disputes. In 1790, members of New York’s Sachem successfully intervened in bringing these skirmishes to an end, and finalized the borders of the colonies by bringing together President Washington and the Indian leaders at a meeting held in Manhattan. The meeting resulted in a treaty signed by the Indians and Secretary of War Knox.

In the ensuing years, men with political aspirations recognized the large assemblies of men at Tammany’s meetings, assemblies, and parades as opportunities and either joined Tammany, or courted the favor of Tammany Sachems. Aaron Burr, recognized Tammany’s influence in his election as Vice-President of the United States, as did Thomas Jefferson (a democratic proponent) who was elected President during the same election of 1801. Politicians, they never forgot the blocks of votes Tammany sent their way.

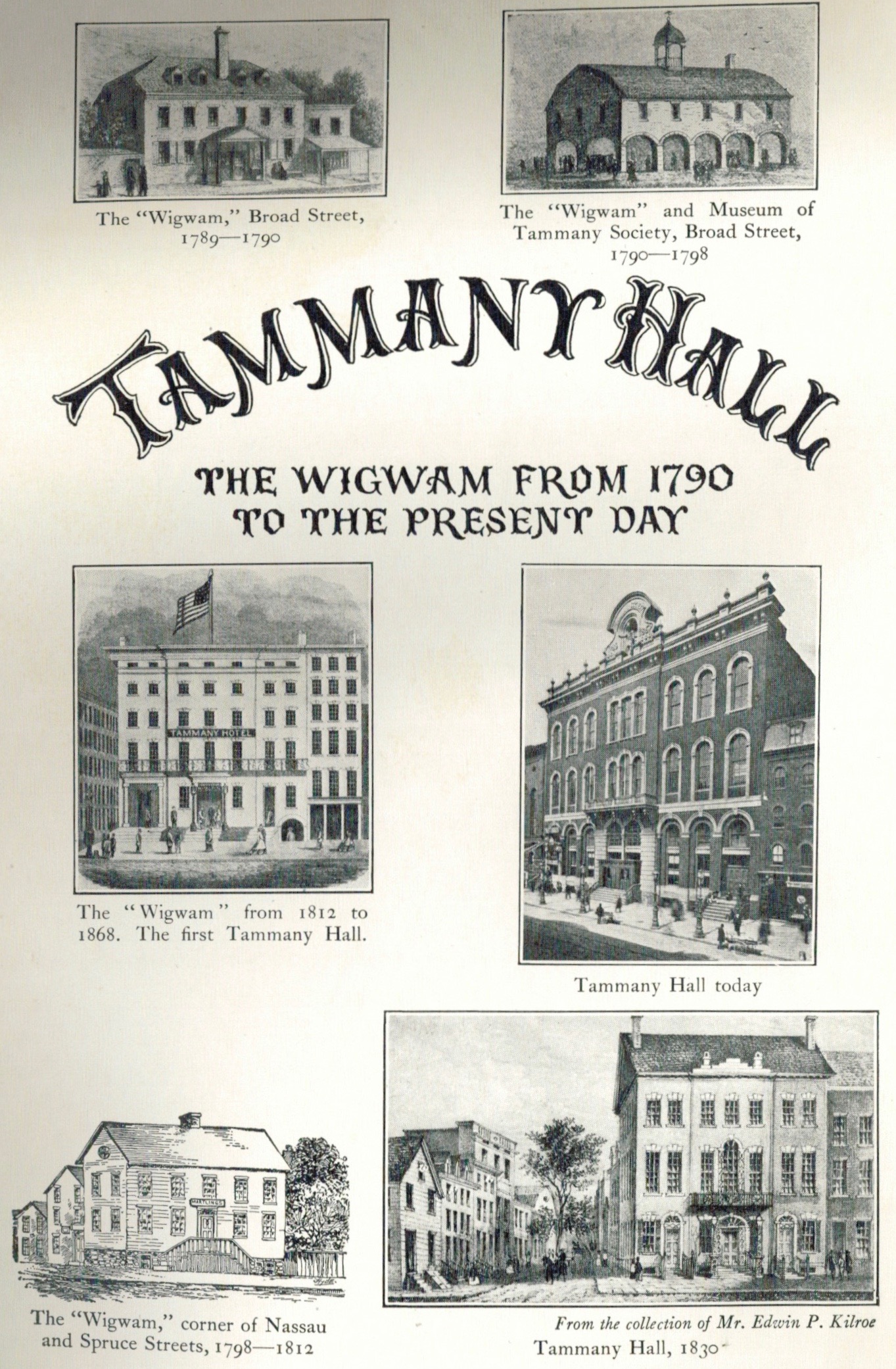

As the country and its government formed, members of associations, including Tammany, would meet in “public houses” (bars) to engage in discourse and debate about civic and societal matters. In 1811, Tammany raised enough money to build their own (first) building, located at Nassau and Frankfort Streets. Such buildings were called “Wigwams.” “Tammany Hall grew by a natural process of social development to be one of the leading organizations of this kind and transformed from a benevolent society to the principal political faction of New York City.” Tammany would hold that position of strength for approximately 120 years.

The War of 1812 brought an end to Tammany’s celebrations, emulations and position as a mediator with the American Indians. The war, fought against the British, was supported by many American Indian tribes. Tammany Hall continued to be a physical location where like-minded men could assemble to discuss common ideas such as politics. “Tammany,” the political machine, was born.

As the number of Irish immigrants in New York City grew, Tammany continued to exclude this large, foreign born, class of voters. Although in 1809, Tammany permitted an Irish-Catholic, Patrick McKay, to run for office in the State Assembly on a “Tammany ticket.” On April 24, 1817, hundreds of Irish men, who had assembled in Manhattan’s Dooley’s Long House, decided that Irish-born orator and poet Thomas Addis Emmett be nominated for a seat in the U.S. Congress. The group expressed their wishes by forcing their way into Tammany Hall, breaking furniture, and battling to a bloody end, with the men of Tammany. The efforts and importance of the Irish continued to be minimized as Tammany’s nativism (or patriotism) became stronger. This xenophobia would soon end and the inclusion of the Irish into Tammany would change Tammany, New York City, its police force, and national politics forever.

Even with Tammany’s potential future windfall in accepting the Irish immigrants into their ranks, their numbers would not truly matter (as voters) until 1821 as it was not until the NYS Constitutional Convention of 1821, that “manhood suffrage” (the inability of those who were not landowners to vote) was passed, as a result of Tammany’s influence. Hence, every man’s vote (white man that was) could now be counted. The later acceptance of the Irish immigrants, and the imminent change in laws, cemented Tammany’s cornerstone in the framework of politics and made it the dominant force in politics at all levels.

Tammany would not recognize the wishes of the Irish immigrant population in New York City until it recognized that the numbers of Irish in the city, which grew exponentially as a result of the Great Irish (Potato) Famine (1845-49), meant more potential votes, and, therefore, greater political strength for Tammany. The Irish immigrants, unlike the Germans that preceded them, already spoke the English language and were similarly adverse to the rule of England. The Irish immigrants, however, unlike their German predecessors, were unskilled in the “trades.” The Irish were skilled at politics, which they were repressed to express in Ireland.

Bibliography: Werner, Tammany, Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc, 1928

![]()

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.