Introduction:

Parts 1 and 2 of this three part series, covered a myriad of technologies used for communication, some of which co-existed for decades. Part 1 ended at the advent of the era of the Police Department of the City of New York’s (PDNY or NYC PD) use of voice radio communication. Part 2 addressed the growing use of one-way radios in vehicles used by the NYC PD on land, sea, and air. The NYC PD’s exhaustive testing and experimentation with two-way radios in the period before, during and after World War II (WWII) set the stage for conversion to two-way voice radio technology. As was the case in the periods covered in Parts 1 and 2, some of the technologies in use in those periods continued beyond the World War II era.

Post- WWII Military Technology Drove Advances in PD Radios

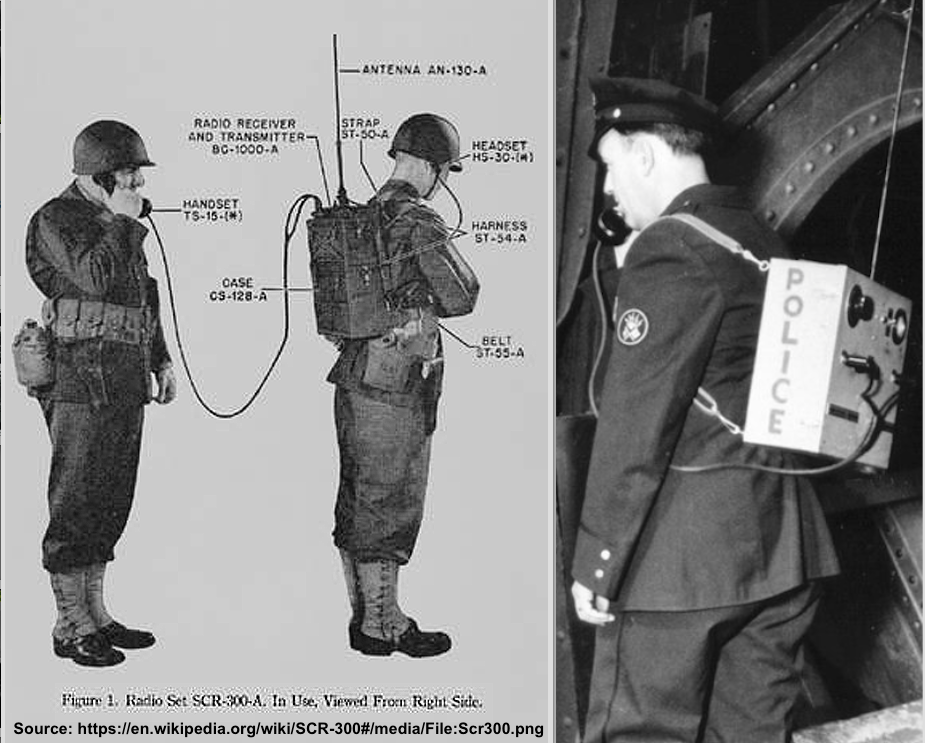

Commercially viable and available two-way radios came into general use after World War II as the equipment became more compact and affordable. During WWII, the U.S. Armed Forces used a backpack style two-way radio called a “Walkie-Talkie,” which as it name implies, allowed the operator to walk and talk on a two-way radio. There was, however, a lag in the NYC PD’s adoption (1945) of the Walkie-Talkie, and the handheld “Handie-Talkie” mentioned at the end of Part 2 of this series. In 1947, Galvin Manufacturing was acquired by the Motorola Corporation and the NYC PD operated Motorola brand backpack radios. These radios weighed thirty-five pounds and operated on the Frequency Modulation (FM) band rather than the less effective Amplitude Modulation (AM) band.

Military Developed and PD Adopted Backpack Style “Walkie-Talkie”

As they did eleven years earlier, newspaper editorials called for the NYC PD to expedite the adoption of two-way radios. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, on May 9, 1946, editorialized that “Now, the New York City police department long has prided itself on its ability to keep pace with scientific progress yet, police cars still are not equipped with two-way radios and there is little evidence to date that it is taking advantage of radar and other wartime discoveries that should prove of invaluable aid in combatting crime.” What was in the minds of the editorial board relating to the NYC PD’s use of radar remains a mystery, but the Motorola backpack radio was a product of the war effort.

PC Arthur W. Wallander who served, from February 1945 to September 1950, under the Mayoral Administrations of Fiorello H. LaGuardia and William O’Dwyer, is credited with advancing the NYC PD’s overdue project of implementing the two-way radio citywide. In March of 1947, PC Wallander’s budget proposal included proposals for 127 additional RMPs.

The plan was to first install the new two-way radios in the outer boroughs where there were no technological challenges such as densely built, high-rise buildings. The plan called for the radios to be installed in Staten Island, followed by Queens, Brooklyn The Bronx, and finally Manhattan. On May 17, 1946, Staten Island became the first of the five boroughs to have full-service two-way radios operating borough-wide.

In 1947, a new vehicle and concept was tested by the NYC PD. The Emergency Service Division (ESD) already had radio-equipped trucks, but they did not have radio-equipped passenger cars. In June of 1947, the first coupe (two door) style automobiles assigned to the ESD began operation in Brooklyn out of Squad (Truck) 16’s Herbert St. Station. These coupes were called “Radio Emergency Patrols” (REP) and carried materials and tools for “primary emergencies.” The concept was that REPs would reach the scene before the ESD trucks and may be able to handle a minor situation thus reducing the number of unnecessary responses by the larger ESD trucks. The trucks would remain on call at the stations along with a Sergeant and a driver. The REPS also performed routine patrol work, and, after a one month, the pilot program was deemed a success.

It was noted that the “mountains” in Brooklyn created radio “dead zones,” however, on August 4, 1947, the NYC PD, declared the test of REPs in Brooklyn a success, and assigned two REPs to Manhattan. The REPs in Brooklyn & Manhattan were equipped with the essentials: oxygen, gas masks, an ax, first aid materials, a ripping bar, a bolt cutter, rubber gloves, a searchlight, “refrigerator keys,” (to rescue persons trapped in refrigerators), rope, grappling hooks, two officers of the ESD.

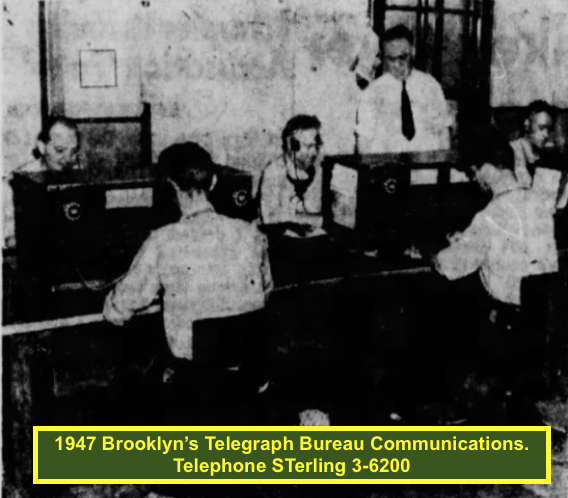

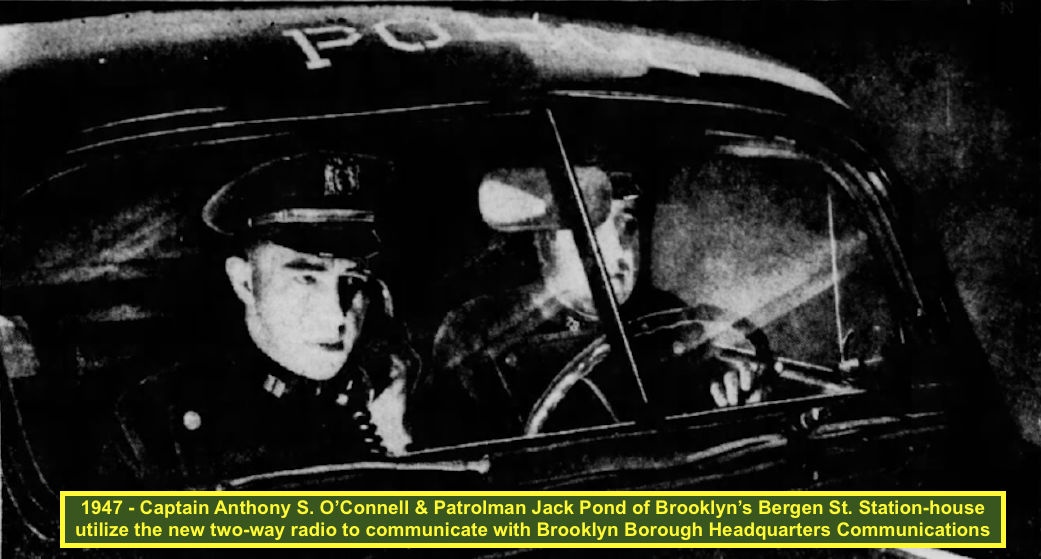

The system utilized the telephone lines and allowed the dispatcher to receive telephone calls from civilians for police services via a headset and to then use the same headset to broadcast and receive radio messages with, for example, Brooklyn’s 103 RMPs. The Radio Corporation of America (RCA) base transceiver (Brooklyn’s call sign was W-R-Q-P), and the 150 mobile transceivers, used a dual band system whereby the base station broadcast on one frequency and the RMPs on another frequency.

As remains the case today with technology, the estimated cost of the technology envisioned in 1937, had decreased by more than fifty percent. The size of the units themselves were also smaller.

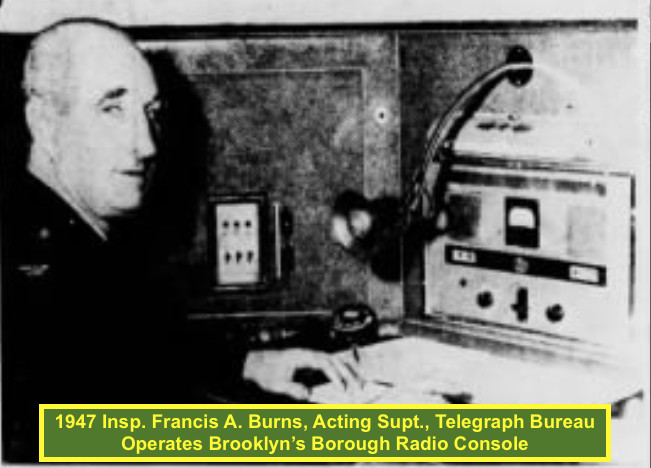

On November 16, 1947, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle published an article regarding the implementation of two-way radios in RMPs in Brooklyn. Under the supervision of Acting Superintendent of Telegraph Francis A. Burns, the base station, located in Brooklyn Borough Headquarters (Atlantic Ave. [Sixth Ave.] & Bergen St.), abolished the need for a commanding officer of a station-house in Brooklyn to call the Manhattan Dispatcher and have a message relayed to a Brooklyn RMP. As a result of the successful use of two-way radios in the four outer boroughs, RMPs in Manhattan would finally receive two two-way radios on August 3, 1947. During ceremonies held at the borough of The Bronx’s borough headquarters, RMPs were connected to borough headquarters on May 13, 1948.

Newspapers that had traditionally relied on listening to PD radio broadcasts over a standard civilian radio and then sending reporters to cover incidents sought an advantage over their competitors. The following week, the New York Daily Mirror, ran an article announcing that they were the first newspaper “to get 2-way police radio alarms” in their Brooklyn office. Essentially, “The News” (as it was and is referred to by New Yorkers) installed NYC PD-compatible radio transceivers in base stations in Brooklyn and in automobiles owned by The Mirror. Receiving real-time NYC PD radio dispatches and RMP radio transmissions gave The Mirror a competitive advantage and photographs of “fresh” incidents began to appear in print.

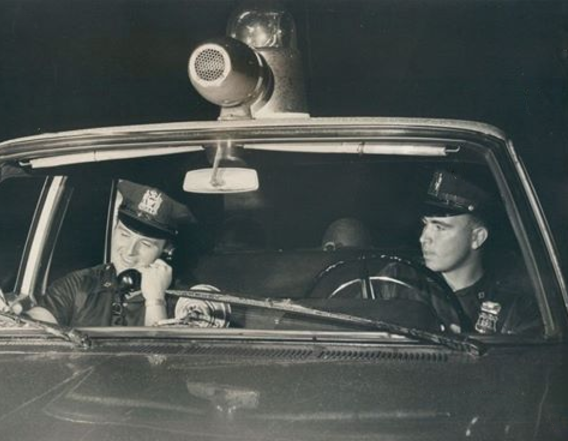

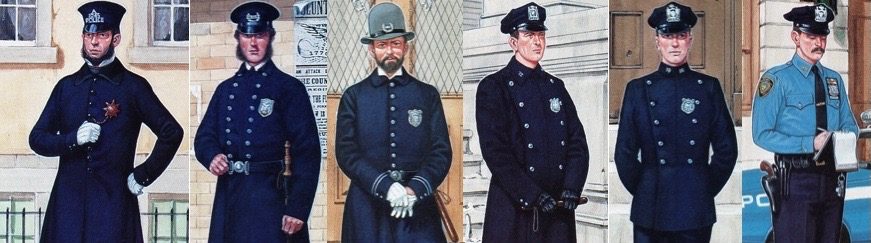

In January 1948, NYC had 10,075 Patrolmen assigned to twenty-two Divisions which encompassed eighty-five PD Precincts, which were further divided into 3,100 foot patrol posts and 260 RMP patrol “sectors.” To this day, NYC PD RMPs are referred to as “sector cars.” Manhattan and Brooklyn had an equal number of RMPs with eighty-three each, followed by Queens with fifty-six, the Bronx with thirty-four, and Staten Island with six. With the addition of each RMP, the number of foot posts was reduced. One key factor in the rapid decrease in the number of foot patrols was simply that two foot posts needed to be eliminated to man a two person RMP. There were a few exceptions where one-man RMPs were in service “when required.” For comparison purposes, in 1932, the “one-way radio era,” there were 801 automobiles in the NYC PD fleet, 325 RMPs and 476 cars without radios. In 1946, there were 829 RMP & other cars equipped all of which were equipped with two-way radios.

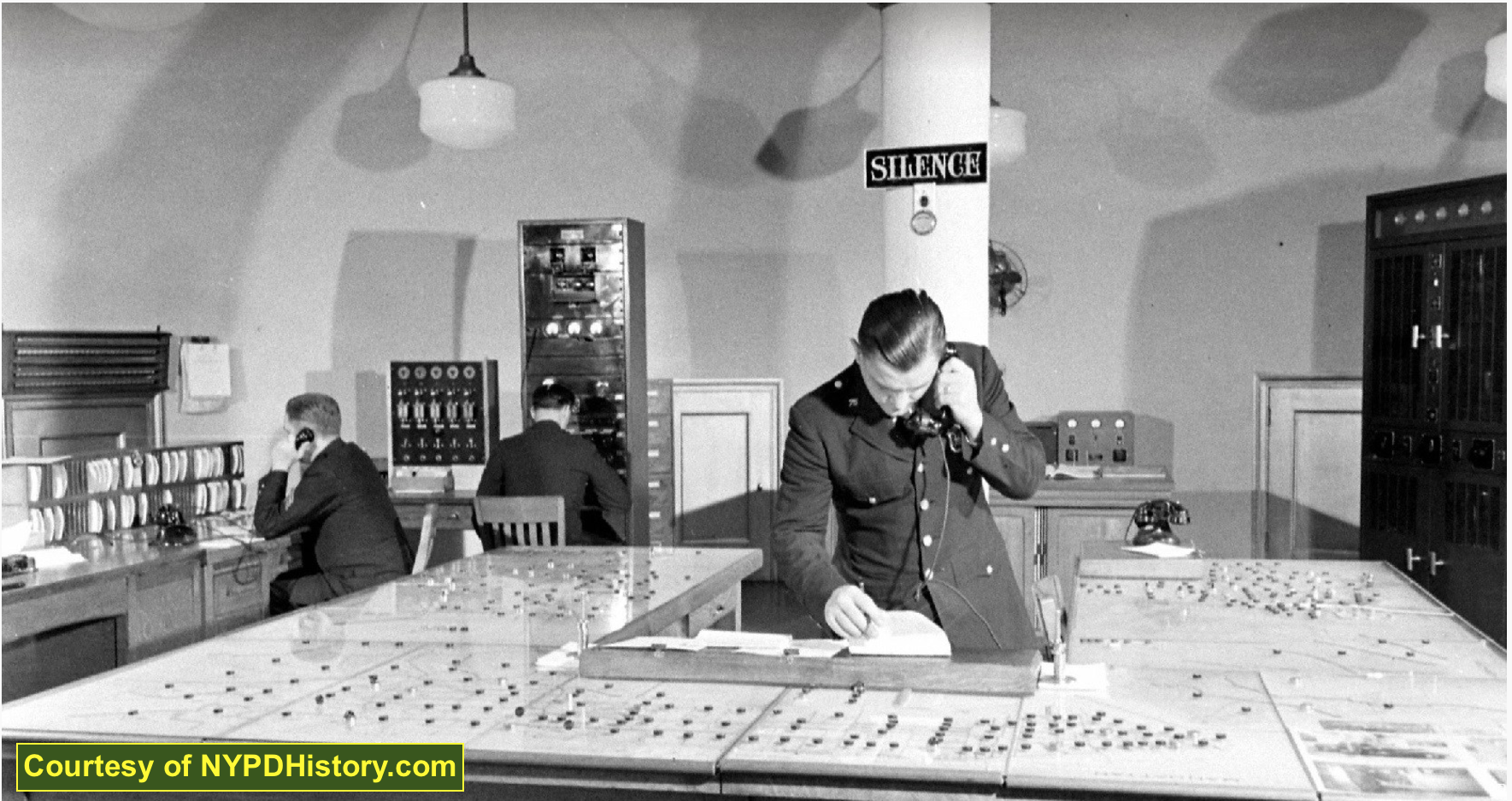

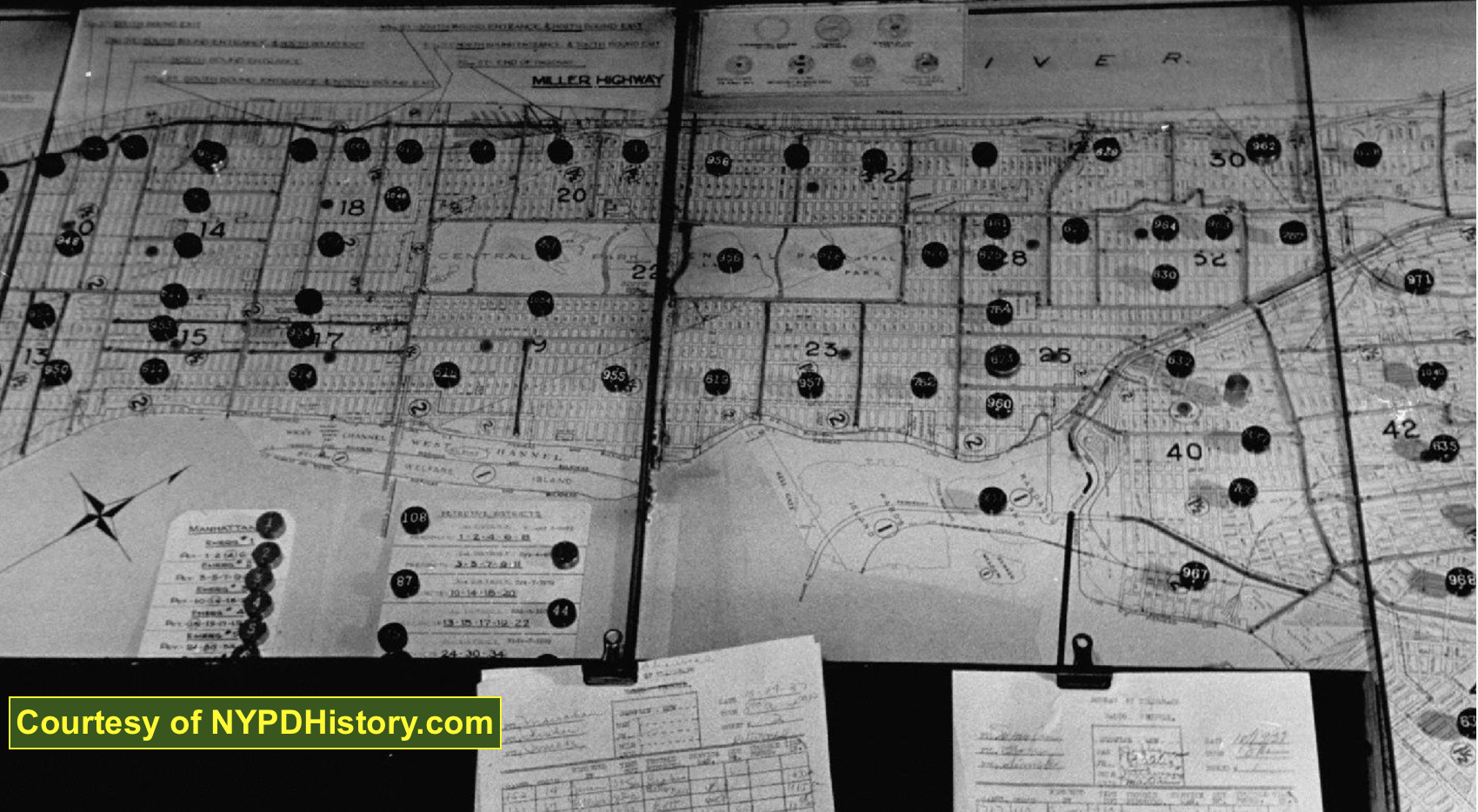

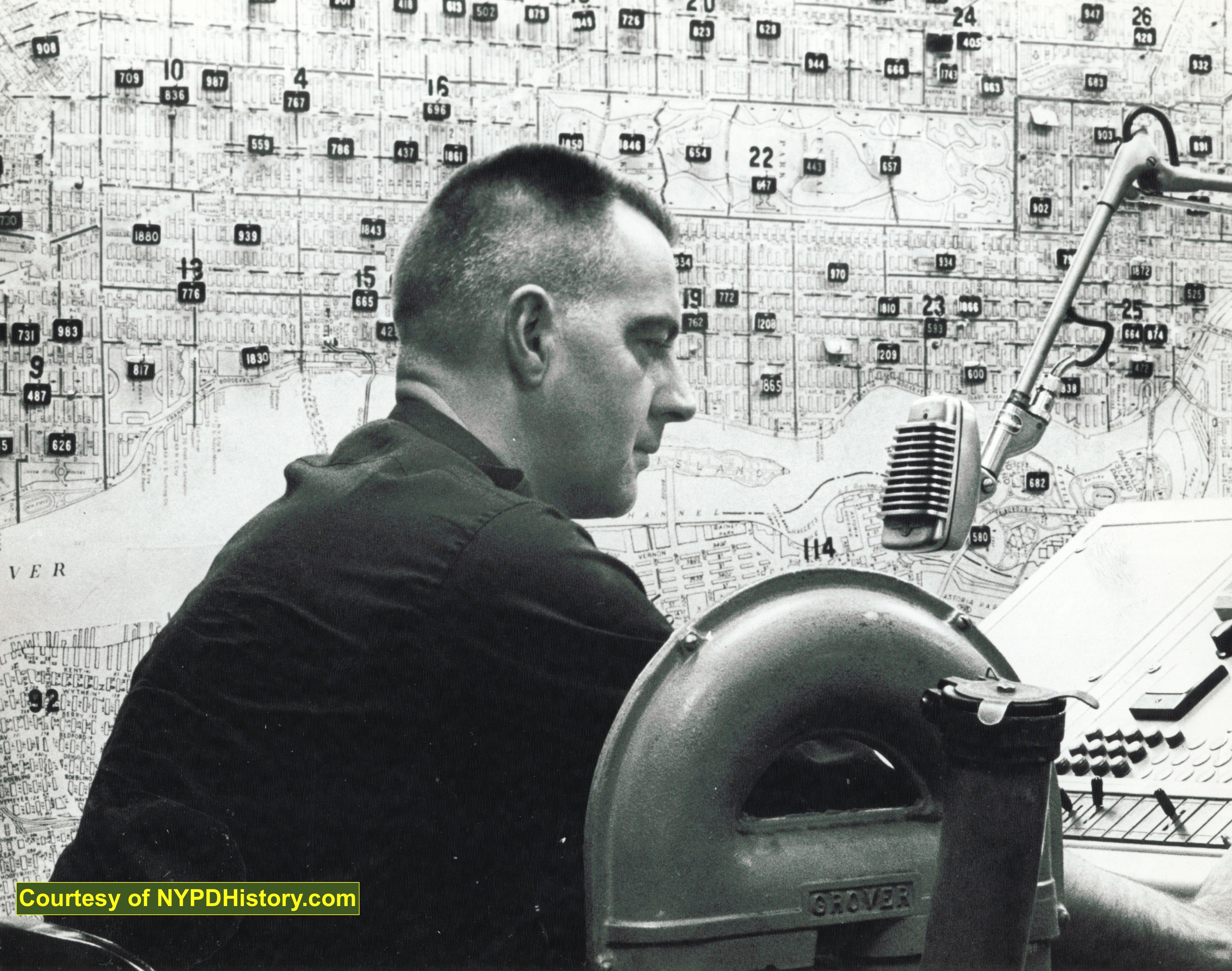

The Telegraph Bureau continued to operate from the same space as it had for decades, the top floor of the department’s headquarters, located at 240 Centre St., Manhattan. Telephone calls for service were received by an officer known as a “Dispatcher,” and relayed by voice to the nearby officer known as an “Announcer,” who used the radio base station to relay the calls to RMPs and other vehicles. The system of table maps and markers remained essentially the same.

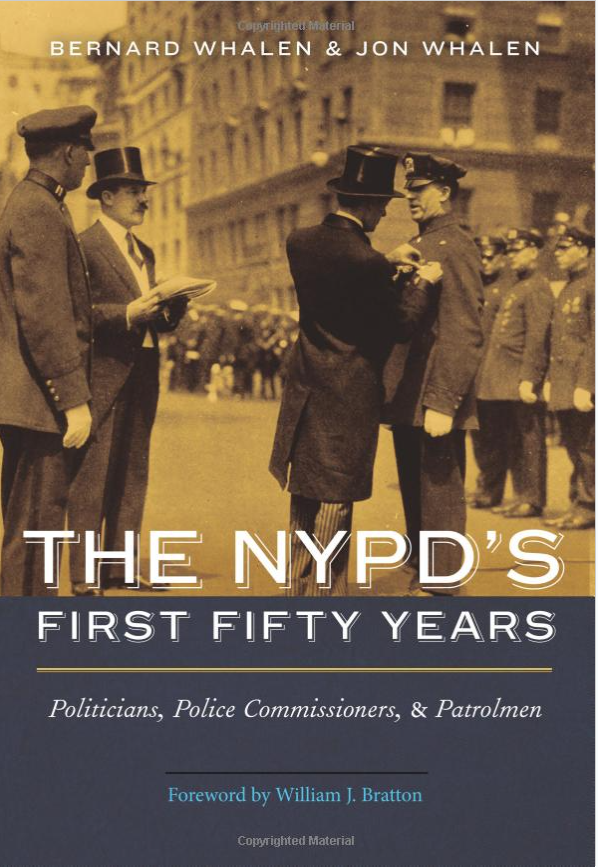

The following description of how the marker system operated comes from one of the finest books written about the history of the NYC PD for the period 1898-1948. The book is entitled The NYPD’s First Fifty Years; Politicians Police Commissioners & Patrolmen, and was authored, by NYC PD Lieutenant Bernard Whalen, and his father, Jon Whalen.

“As soon as a call for service was received by the main switchboard, it was routed to the dispatcher. he scanned the table map to determine which radio motor patrol car should respond. Whenever a radio car was available for assignment, the disk displayed the vehicle’s code number on the white side. Once the dispatcher made the decision, he passed the information over to the announcer who transmitted the alarm to the radio motor patrol designated by the dispatcher. Other radio cars in the vicinity were expected to respond as backup.”

Whalen relates the verbiage of a typical radio transmission which differs from that of today. “A typical radio-run transmission from the announcer would be as follows: “Car Number 292- Northeast corner Lenox Avenue and 125th Street, Manhattan – Signal 30. Authority Telegraph Bureau – Time 1:43 p.m.”

In 1948, a citizen advocacy group issued a report which proclaimed that there was a cost benefit, to reducing the number of two-man RMPs and increasing the number of one-man RMPs. The group’s plans had no effect on the PD’s practice of tel-man RMPs as was indicated in NYC PD report following testing of the same,

1950 Ford RMP 75th Precinct Linden Blvd., Queens

Operation of a radio in a RMP required completion of a training course at the Police Academy. In 1948 and 1949, an average of 1,300 men received training in the “RMP Operator’s” Course.

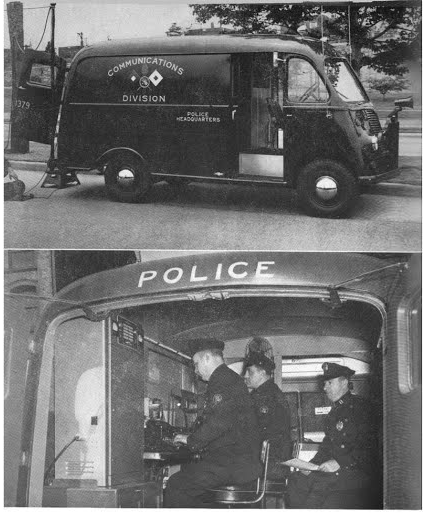

On the occasion of the city’s Golden Anniversary Parade held in June 1948, PC Wallander debuted a four and one-half ton “Mobile Police Headquarters,” which was the first vehicle to bear the name “Communications Division.” Effective midnight on June 21, 1948, PC Wallander issued a General Order which re-designated the name of the Telegraph Bureau to the “Communications Division” to reflect the changes in technology and its “modern scope.” The Mobile Police Headquarters truck was stored in an old old firehouse, located in Long Island City, Queens. In 1952 a new “Temporary Headquarters Vehicle” (referred to by the abbreviation “THV”) was purchased. Equipped with desk space and office equipment used to prepare reports, a two-way radio, radio-telephone, and the capability of connecting to the lines of any PD Signal Box or Public telephone, the truck was capable of managing and coordinating the scenes of emergencies. These trucks were later designated as “Command Posts,” or “CPs” and continue to be referred to as such today.

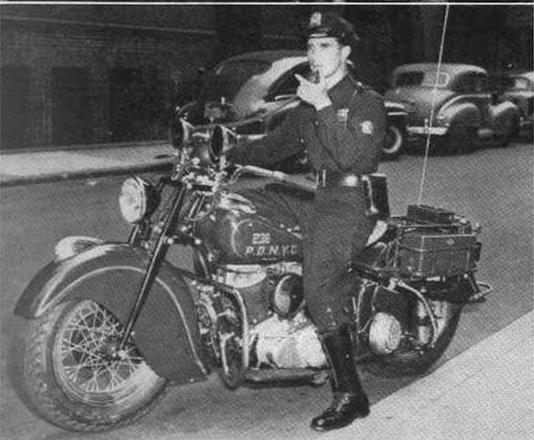

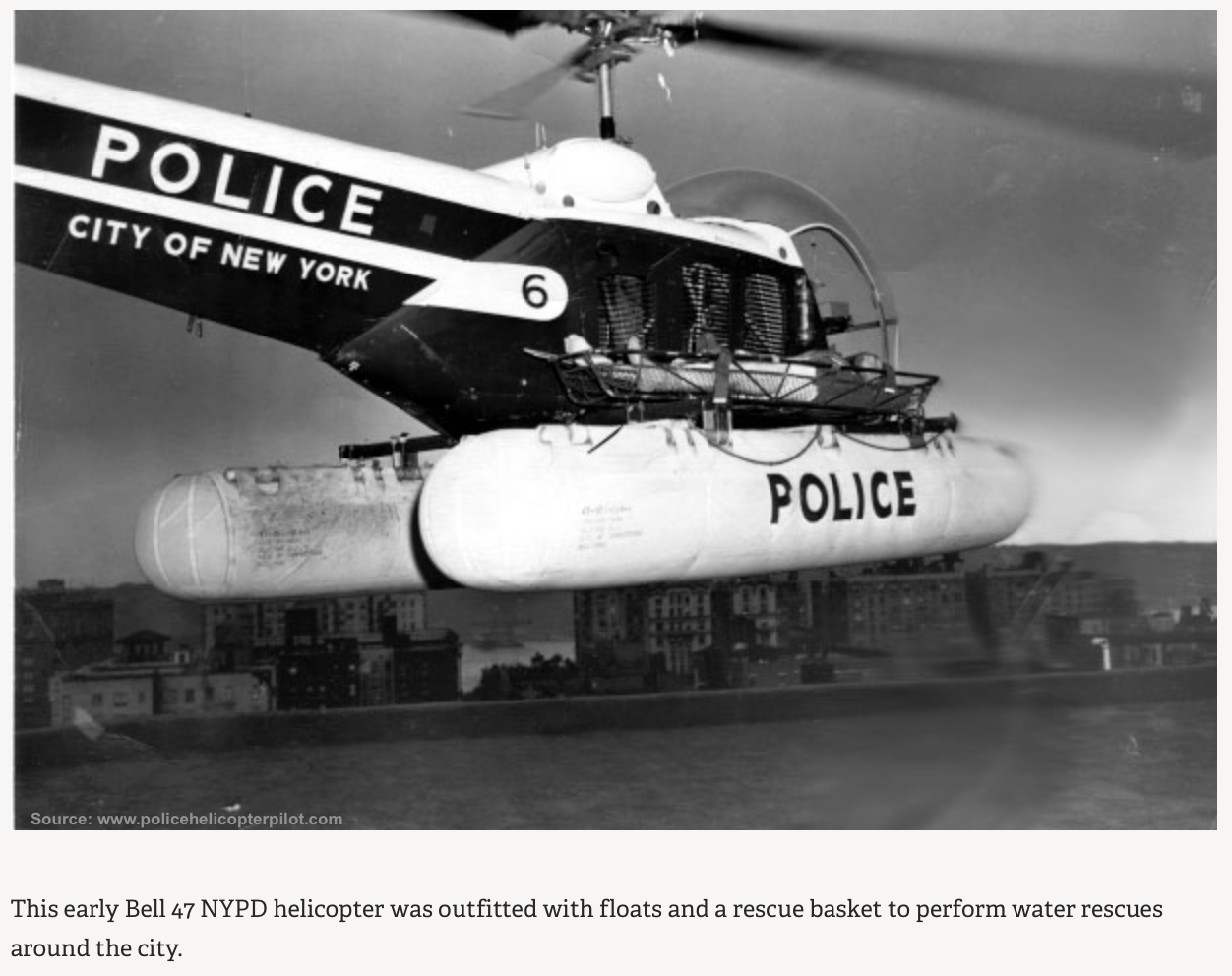

In 1949 the ESD’s fleet consisted of twenty-four trucks, forty REPs, two Bomb Carrier trucks, an Emergency Delivery Truck, three ESD Ambulances, two Medical Unit Trucks, and a Light Truck. The ESD responded to over 15,300 emergency calls. In December, citywide REP service was implemented. Other PD vehicles equipped with two-way radios, in 1949, included: eleven boats, four airplanes, one helicopter (a Bell D-47, placed in service on October 1, 1948) and two motorcycles (an Indian Brand placed in service on July 23, 1949).

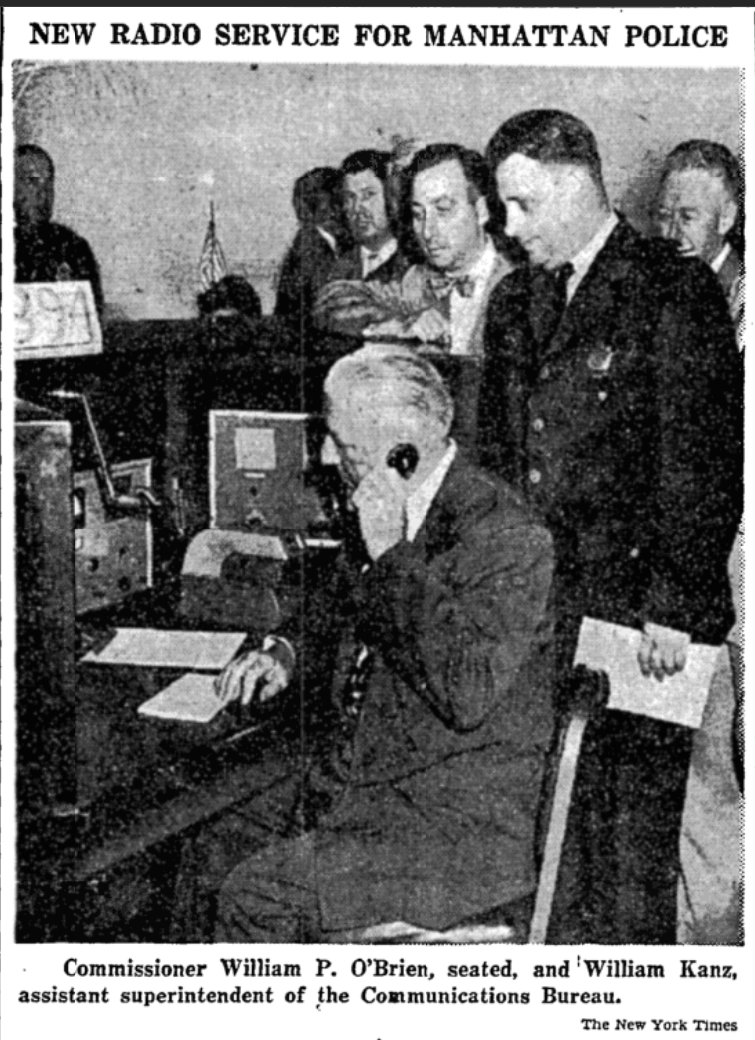

On August 9, 1950, PC O’Brien, accompanied by 200 ranking members of the PD, celebrated the completion of two-way citywide radio communications between headquarters and vehicles in all five boroughs. It was noted that Deputy Chief Francis J Burns, Superintendent of the Communications Bureau, who had managed the PD’s old Telegraph Bureau and every technological advance for nearly three decades, was too ill to attend, but he participated in the event from his home where a PD radio had been installed for this purpose.

In 1950, there were 232 RMP sectors citywide and seventeen unmarked, high-power, Detective Cruiser RMPs that operated twenty-four hours per day. In March of 1949, PC William P. O’Brien abolished the Detective Cruiser RMP program, releasing the plainclothes Patrolmen and Detectives from patrol duties.

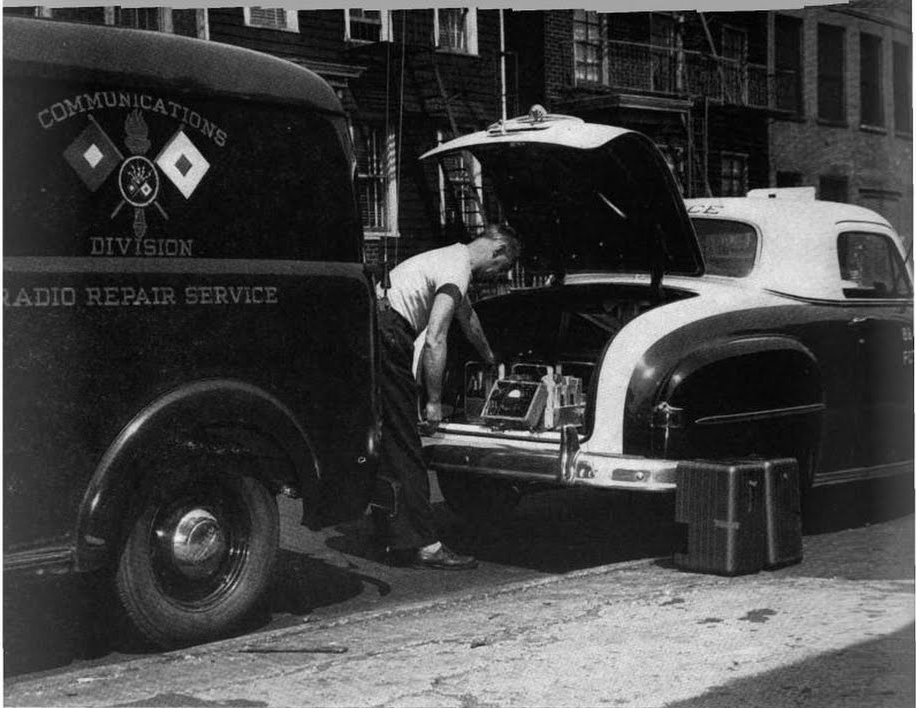

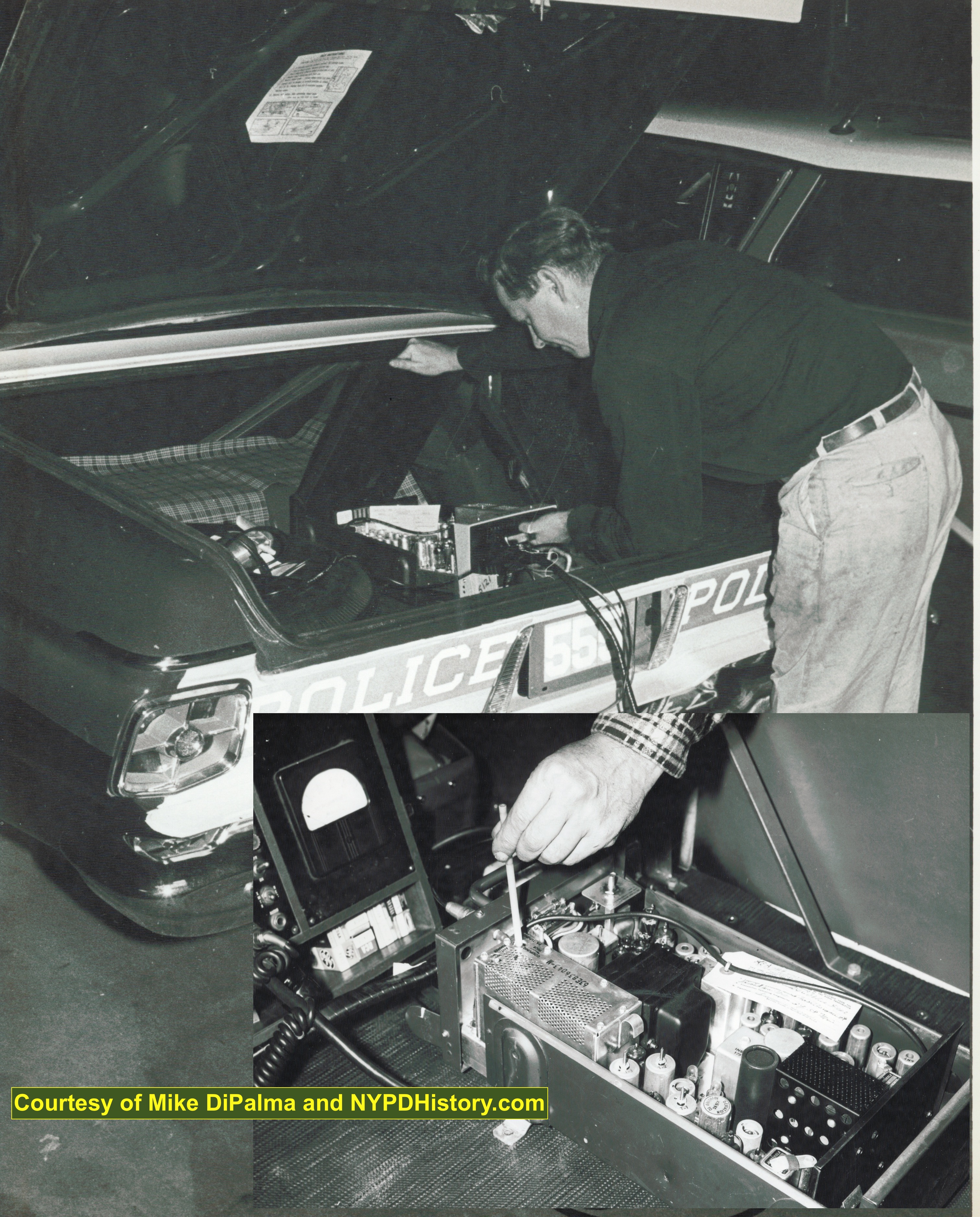

The NYC PD Communications Division operated a small number of trucks designated as “Radio Repair Service” vehicles. Operated by skilled technicians, these trucks were capable of responding to a RMP, CRMP, REP, and any other radio-equipped vehicle rather than requiring the same to report to a central repair shop. The Radio Repair Service trucks were capable of removing non-functioning radios from vehicles and completely replacing the same with a working unit. Radio repair shops were located in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens. While a RMP was under repair, one of the officers from the car under repair was required to sit in the repair truck and make note of all alarms.

In 1951, there were six walkie-talkies in use with expectations of the delivery of fourteen additional units. The units were destined for the Emergency Service Division’s Trucks for use at major incidents. Other innovations in 1951, were the installation of “Precinct Radio” receivers, which were speakers installed throughout a precinct building so that all officers could monitor radio transmissions. Additionally, in a throwback to the Flash Light Recall System (covered in detail in Part 1 of this series), a Selective Call System was utilized by the PD. Essentially, when officers were out of their RMP and Central needed to convey a message to them, Central could send a signal to the emergency lights atop RMPs. The signal would activate the light which signaled the officer to return to the RMP and use the radio to receive a message.

If you listen to a radio transmission today, the NYC PD’s various vehicles and portables use the term “Central” as the designation for the operator of the base radio dispatcher. The term “Central” originates not from the centralized radio communications centers, but traces its origin back to the era when there was no dial on a telephone. Someone desiring to reach a number would pick-up the receiver and wait for an operator at the “Central” telephone company switchboard to answer and ask what number the caller wanted to be connected with. The operator would then make the connection (literally) by plugging a wire into a port for the person to be called’s telephone.

It would not be until May 2, 1951, that a limited number of Transit Police Department automobiles would be equipped with two-way radios. In November 1951, city ambulances had not yet adopted the technology. In January, 1952, the NYC Board of Estimate approved funds for the installation of two-way radios in the city’s ninety-four ambulances, which were dispatched by the PD.

In what may have been the first act of defiance by way of a NYC PD two-way radio, on December 21, 1951, Mayor Vincent R. Impellitieri and PC George P. Monaghan broadcast a Christmas message to the officers in 1,060 RMPs, thirteen Harbor boats, one motorcycle, ten ambulances, and three airplanes. A response from an unidentified unit said “Never mind the speeches and sob talk; give us more money.” It would take nine years for the NYC PD to attempt to curb such comments when, in 1960, miniature tape recorders were installed in selected RMPs in order to eavesdrop on radio communications.

In 1953, the ESD added ten station-wagon type automobiles to their fleet that were capable of carrying equipment or being readily convertible for use as an ambulance.

In 1953, the NYC PD, in order to keep up with the changing technology, began the process of replacing the six year old radio equipment in RMPs assigned to the Borough of Queens as well as base unit antennas. Additionally, “the latest” police and aviation radio equipment was installed in two of the PD’s helicopters. New, modern Signal Boxes and a new, modern telephone system were purchased.

The Rules and Regulations and MOP in 1956, contained a chapter entitled “Communications Services” in which all of the rules, regulations, and procedures relating to the various methods of communications were outlined in great detail. The methods of communication listed were: telephone, telephone switchboard, teletype, radio, and public address. The public telephone number for Manhattan Headquarters, 240 Centre St., was “SPr-3100.” The number for police officers who wished to be connected with the Manhattan Communications Bureau was “CAnal6-2000.” SPR-3100 was the title given to the NYC PD’s monthly magazine which was mailed to all active and retired members on a subscription basis.

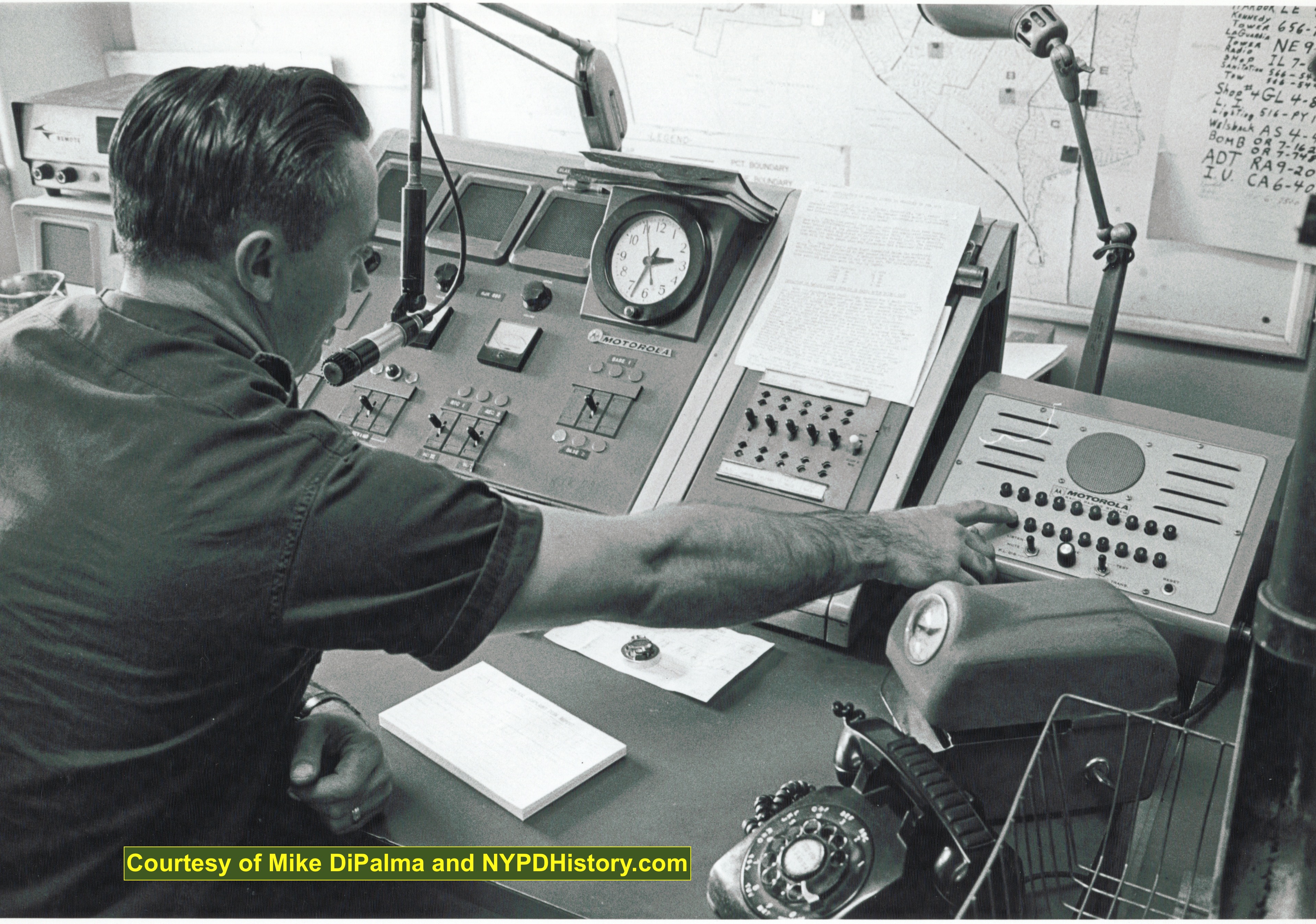

Two-way radios began to replace one-way radios in 1947, and the 1956 Rules & Regulations & MOP reflected the change. Additionally, there were seven radio transceivers located throughout NYC, each with their own call sign. Dispatchers were still resident in the same precinct where the radio base stations were installed. Eventually base stations were made capable of being controlled remotely with the first centralized radio operation, located at headquarters in Manhattan.

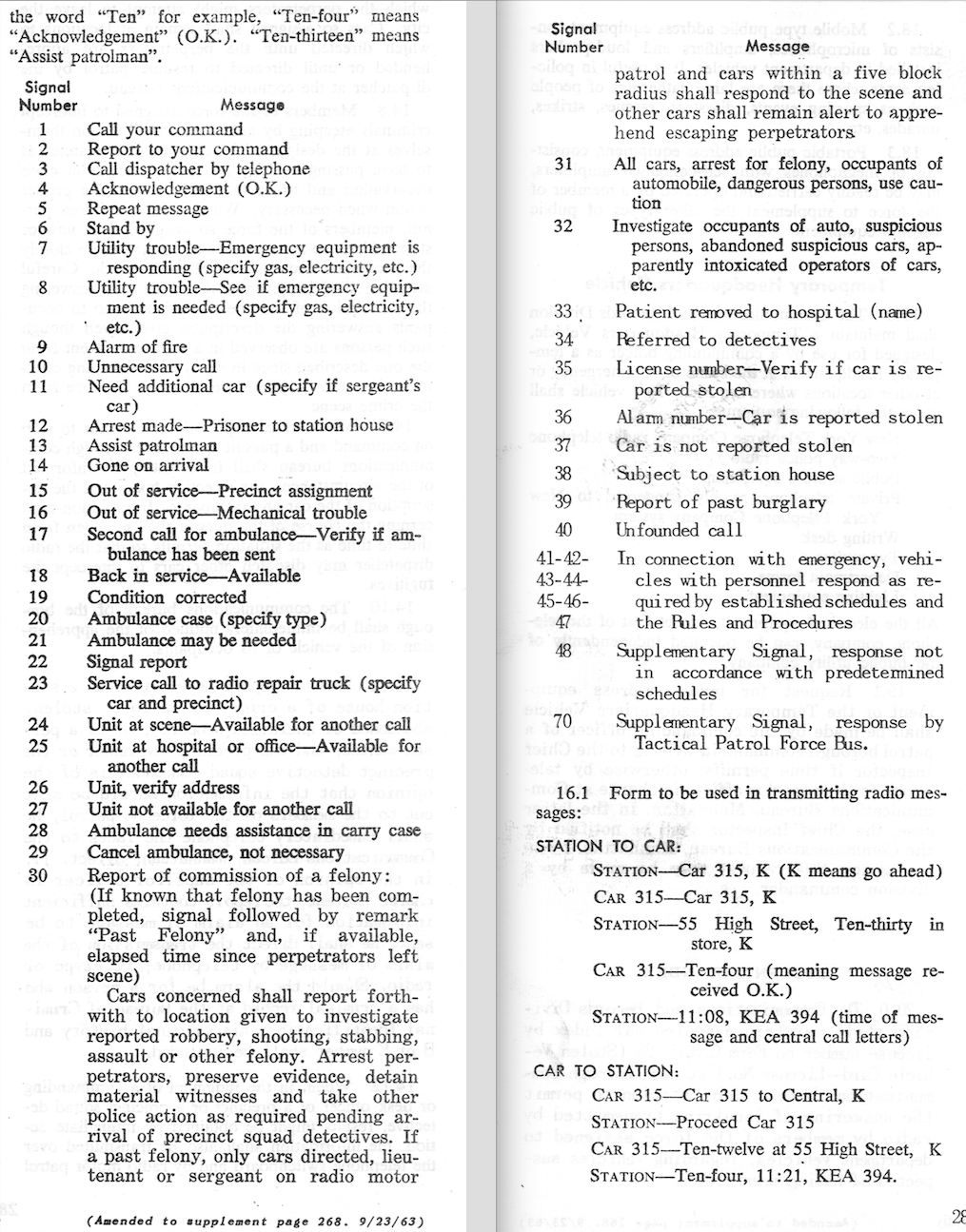

The same source indicated that the use of teletype messages and alarms had extended to more states and that a “Ten Code” had been established.

The Teletype System Expands

The Teletype System would remain an important component of the overall communication abilities of the NYC PD. In 1949, the PD was able to communicate intra-departmentally with all precincts and commands via a centralized command center located in the Manhattan’s Communications Bureau, located in headquarters. Inter-departmentally, the NYC PD was able to send and receive teletype messages with almost all states east of the Mississippi River and via radio-telegraph with departments from the Gulf of Mexico to the Great Lakes.

Early Developments of Technologies of the Future

Other innovations and advancements included: a radio-operated typewriter, which operated in the same way as a teletypewriter, but used radio (wireless) signals to send the message as opposed to wired lines; a telephoto facsimile device used by vessels at sea to receive newspapers, navigational charts, and weather maps was in use and it was projected that such a device would be beneficial to police work; and lastly, television was in its infancy, but the vision of its use by the police of the future was already a topic of discussion in 1938.

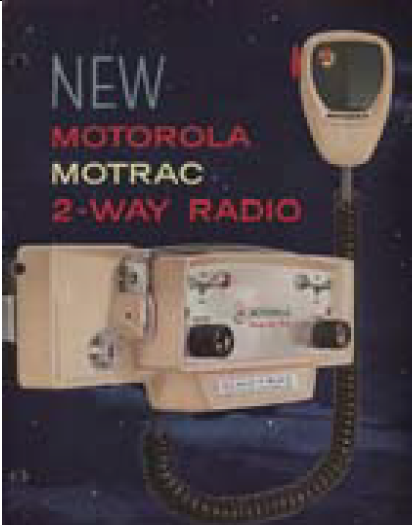

In 1955, Motorola introduced a new technology, the transistor, which was far smaller and more energy efficient than the tubes used for decades. In 1957, the NYC PD had 690 RMPs and, in 1957, studied the feasibility of equipping the 3,780 foot patrol posts with two-way radios. In 1958, Motorola introduced the world’s first two-way radio, called a “Motrac,” designed for vehicles which utilized a transistorized power supply and receiver. The old tube style radios required that the vehicle’s engine be running, while transistors utilized a battery for power.

In 1957, there were 405 RMP sectors and the department conducted a research study on the feasibility of equipping Patrolmen on the 3,778 foot posts with portable two-way radios. In 1960, there were 691 radio-equipped vehicles.

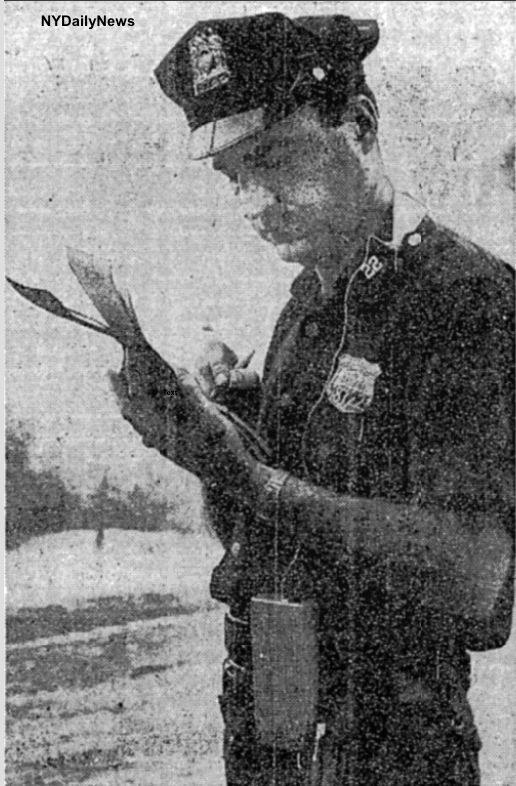

An alternative to equipping all officers with the larger, and more costly, two way portable radios was studied by the NYC PD. After a 1958 testing period in the Central Park Precinct, park Patrolmen were issued small, pocket-sized transistorized radio receivers which were tuned to a NYC PD frequency. In 1959, twenty receivers were issued to Patrolmen in Central Park. These radios were also utilized at parades, ball games, and at large incidents. In Central park, there was available a ten pound two-way portable radio that was deemed “too heavy for any man for an eight hour tour of duty.” The radio was used by either a supervisor or the senior Patrolman.

There was a demand for portable radios that would permit officers to remain in contact with headquarters while outside their RMP’s. Aerotron made a portable mobile radio that was large, and had a rounded handle that looked like a water bucket, hence the nickname “Bucket Radio.” While these large, heavy radios were proved impractical for RMPs, they were used effectively at large gatherings/incidents.

In light of the fact that his name has been mentioned in all three parts of this series, it is noteworthy to mention that Assistant Chief Inspector Francis A. Burns, Commanding Officer of the Communications Division, retired on February 1, 1960, at the age of sixty. Burns was a member of the department for thirty-nine years and was in charge of the Telegraph Bureau and Communications Division since 1943. It is likely that Burns’ foresight and accomplishments in the field of communications at the NYC PD remain unrivaled to this date.

About 1961, the NYC PD utilized a closed-circuit television system to broadcast, from Headquarters, the daily “line-ups” of criminal suspects arrested overnight to Detectives in Brooklyn, thus eliminating the need for them to travel to Headquarters.

In 1962, Police Commissioner Michael J. Murphy, formed the “Planning Bureau,” to review and issue a report on long-range planning as a strategic weapon against crime. On July 13 of the same year, a new rank of “Assistant Chief of Planning and Commanding Officer of the Planning Bureau” was established and Robert Gallati was promoted to fill the position. The Bureau consisted of the following Groups: Personnel Research (maximize effectiveness of manpower); organization and Management (management analysis, records administration); Living Laboratory (experimentation and pilot studies); and Operations Research (technology, computers. strategies). The Bureau issued a report on their findings and recommendations.

The report that was issued as a result of this bureaucracy, contained the following (relevant to this article) initiatives: utilization of television for training purposes and communication, photostatic copies of communications, implementation of an electronic business machine for processing licenses, dictation equipment for use of Detectives; the purchase of an IBM computer for fingerprint analysis, use of RMPs in combatting gambling and public moral offenses, and the invention of an “Imagemaker” to supplement the work of suspect sketch artists.

PC Murphy acknowledged that the “Change Agents” in police work who drove the initiatives set forth in the report were elevating law enforcement to a higher level of professionalism which would result in higher wages and more efficient use of limited resources.

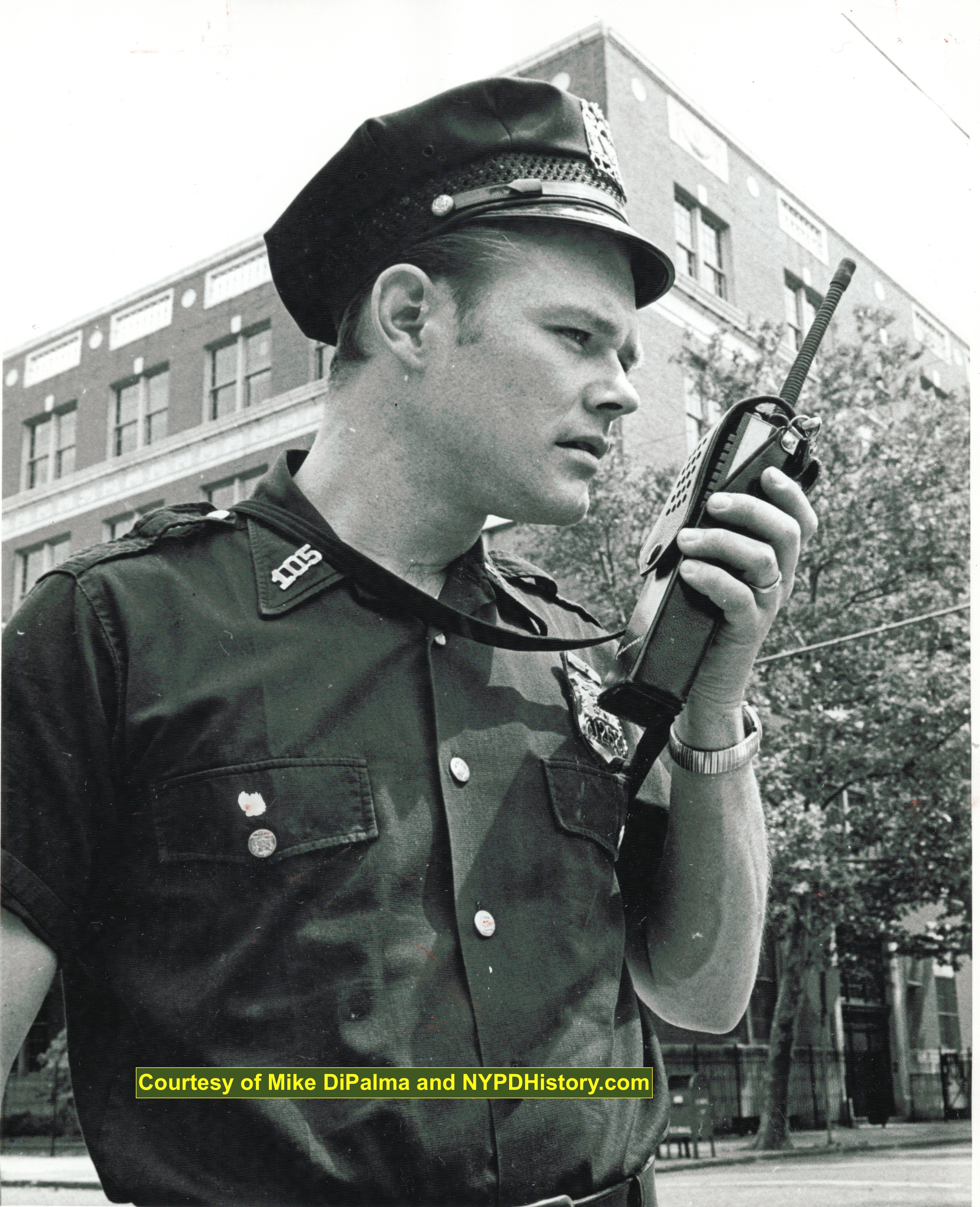

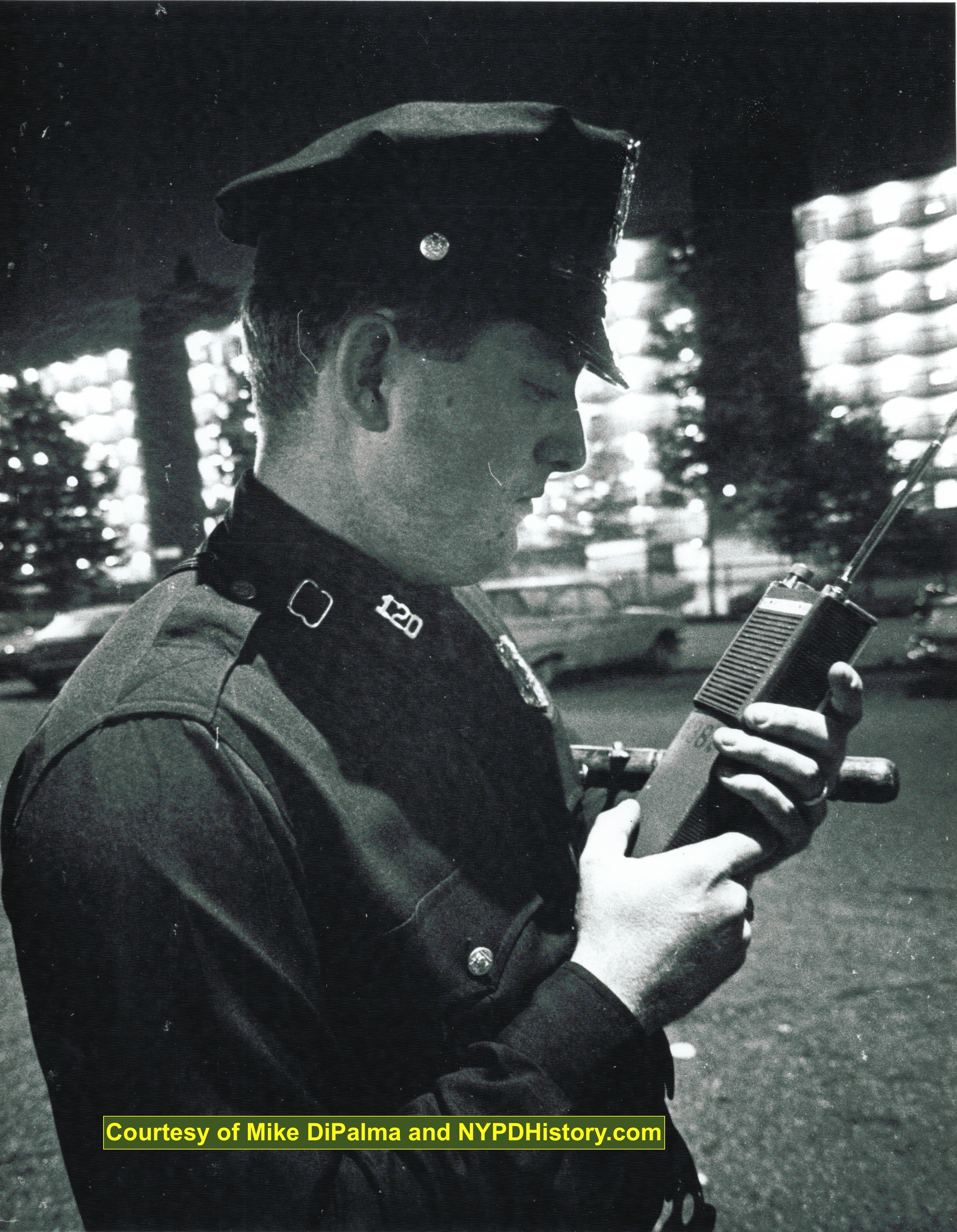

In 1962, Motorola introduced the first commercially viable portable hand held radio, the “Handie-Talkie HT200,” referred to by users as the “brick.” In the mid to late 1960’s the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) authorized use of the Very High Frequency (VHF) spectrum and the NYC PD replaced the Low Band frequency radios with models operating in the VHF range. The additional spectrum meant the availability of more frequencies, hence the new system allowed a NYC PD “Division” (which consisted of two or more contiguous precincts) to share the same frequency. Mobile (car) radios were only capable of using two frequencies, one for the precinct, and the other for a borough or adjacent division. If more frequencies were required, another mobile radio was installed. Dispatchers remained resident in the same precincts where the radio base stations were installed. Eventually base stations were capable of “Remote Control” with the first “Central” dispatcher located at headquarters in Manhattan.

There were technical issues with the addition of portable radios since communications were “simplex,” or radio-to-radio on the same channel. With a 30 watt mobile radio, range was not an issue, but with a 2.0 watt portable range was a challenge. To overcome that, an overlay of a “Repeater System” was developed. The Repeaters were high powered relays mounted atop an apartment house or similar structure within the a division (a designation referring to a grouping of two, or more, contiguous precincts). The portables transmitted on one channel, which was automatically rebroadcast on the division channel. It worked well and eliminated the necessity of changing the channel components on hundreds of mobile radios. Eventually the HT-200’s were replaced by much smaller and lighter Motorola FFN Series “Slimline” radios.

In 1965, Motorola introduced the next step in technology, the smaller and more efficient transistor. In the mid to late 1960s there was a demand by the rank and file for portable radios which would allow officers to remain in contact with Central when outside their RMPs. In October of 1967, the NYC PD announced plans to adopt new, and update existing technologies.

In 1967, fifty-six radio-equipped motorcycles were added to the fleet and Motorcycle officers were trained to use their motorcycles, or “wheels” as they were long-referred to, for crowd control. Additional equipment purchased in 1967 included fifty recall lights (for the now revolving emergency lights) for RMPs, 100 walkie-talkies, ten portable base stations, and other miscellaneous items. Additionally, the previous practice of referring to RMPS solely by a unique number, such as Car 257, was abolished and replaced with an alpha-numeric system that used the precinct number combined with an alphabetic designation, such as “43 Charlie.” This designation system, using the precinct number and Sector Car designation, remains in use to this day.

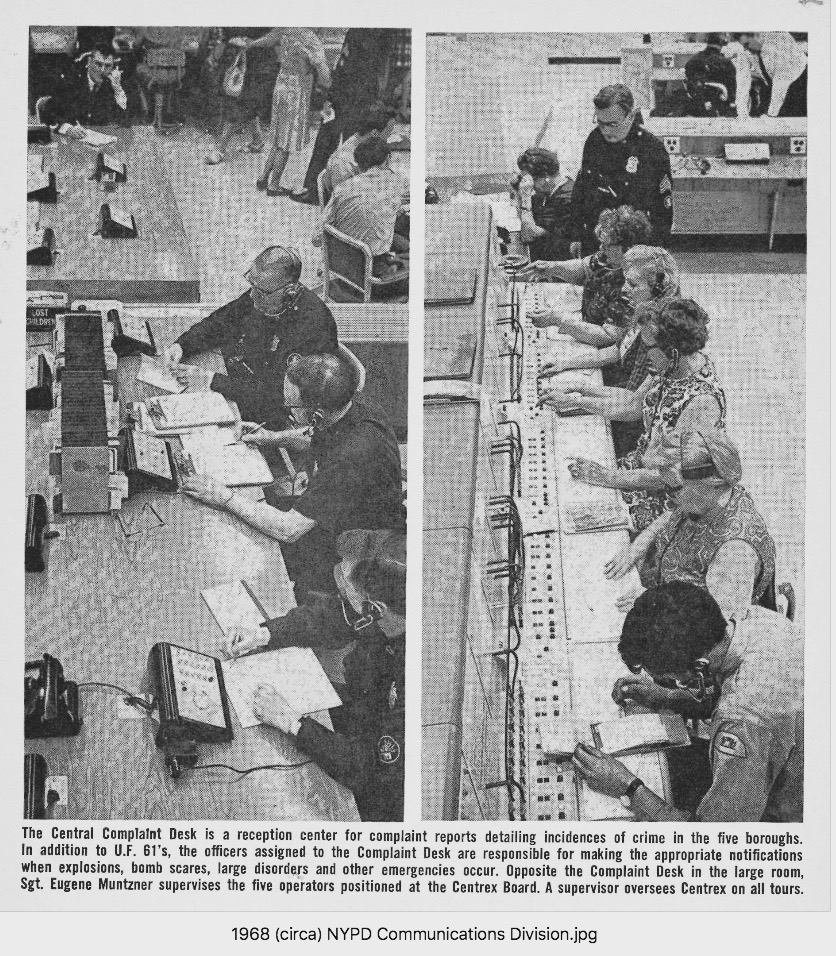

Prior to 1968, RMPS calls for service from the public via public telephone, or PD Call Boxes, were received at headquarters on Centre St. headquarters then utilized the two-way radio to dispatch the RMPs, and other vehicles. In the summer of 1968, the NYC PD undertook a massive re-organization, requiring re-construction of facilities, towards to goal of establishing a centralized Citywide Communications Bureau at Headquarters.

In the summer of 1968, the new, “ultra-modern” Centralized Communications Center was completed at a cost of over one million dollars. The centralization was reported to have reduced the span of control over RMPs, by having all RMPs (and other vehicles and radio-equipped officers) dispatched by one center. The centralization also provided a speedier response to calls for assistance, and improved overall efficiency. Two-way radios were installed in the new three-wheeled Scooters and portable radios were available to nearly every foot patrol officer.

On the date that the center was opened, the NYC PD was the first PD in the nation to utilize a three digit telephone number for emergency calls, the familiar “9-1-1” that is still utilized today. Another advancement was the link between the communications system and the departments computerized information system called “SPRINT.” The Special Police Radio Inquiry Network (SPRINT) permitted officers in the field access to inter-departmental databases and intra-departmental databases such as motor vehicle agencies, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC) and the New York Statewide Police Information network (NYSPIN) which were a means of communication (teletype messages) as well as a repository for stolen, lost, wanted persons and objects.

The new forty-eight position switchboard routed non-emergency calls to an information desk at Headquarters and emergency calls to the appropriate borough dispatcher. The emergency process required the switchboard operator to complete an information card which was sent via a conveyor belt to the appropriate dispatcher (twenty-four in total). The dispatcher transmitted the call to the RMP and the status of PD vehicles was displayed on an electronic screen. The screen replaced the map board checker system that was used for decades.

Finally, 1968 marked the year that the radio-teletype system, proposed years earlier, was finally installed on a limited basis for testing.

In the early years of the 1970s, plans were announced to install television cameras in police helicopters for the purpose of broadcasting traffic and incidents to headquarters (and possibly the public). The cameras were monikered the “eye in the sky” and began operation in June of 1971.

Plans were announced to combine police and fire alarm boxes which would permit voice communications between citizens and dispatchers. Another proposal was to equip fifty RMPs with teleprinters (radio controlled printers) mounted under the dashboards to relay information to officers. The major budgetary proposal was the construction of a new police headquarters, to be build on Park Row, to replace the headquarters on Centre Street, which had been occupied since 1909.

The same proposed items were still in a proposal state in October of 1970. Additionally, the 1970 proposal contained a $1.3 million line item for the purchase of 700 mobile two-way radios and base stations that would operate in the ultra High Frequency (UHF) range, as well as $800,000 to replace 800 “walkie-talkies” with more modern, four-channel “handie-talkies.” This change required both new mobile (RMP) and portable radios as well as dispatcher console radios. As with the VHF system a repeater type operation was required but, this time it was designed ground up in a universal configuration instead of the previous repeater overlay. Centrally located repeaters were installed in the heart of the divisions. The then separate NYC Housing Authority Police already had their own independent UHF radio system.

Additionally, it was proposed that $120,000 be spent for 100 closed-circuit television monitors to be installed in station-houses and $50,000 “to experiment with the printers in squad cars, devices that would prompt out orders from headquarters, even when the men were out of the car on assignment.” The concept of transmitting orders to RMPS via radio signals would not be realized until the introduction, in 1999, of the “Mobile Data Terminal” which was manufactured by Motorola.

The HT-220s were replaced by the Motorola MX-340 and MX-350 series in the late 1980’s. Affectionally known as “the brick,” because of its size and shape. Reports from retired officers indicate that these portables may, at times, have been used as a defensive weapon. The four channel MX-340 was used by precinct personnel. A specially modified eight channel MX-350 was designed for use by Neighborhood Stabilization (NSU) units which had to work in a wide area as well as specialized commands such as Highway and Emergency Service.

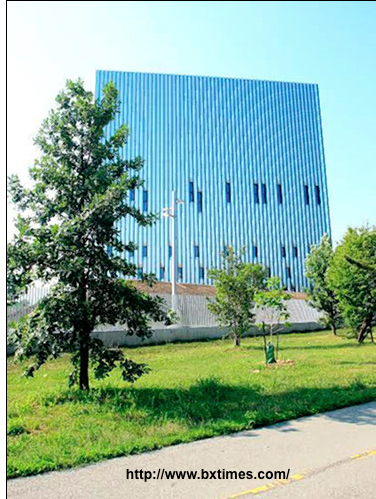

In 1992, when space at One Police Plaza was insufficient to handle the increased size of the 9-1-1 system and radio dispatchers, operations were moved to the new “MetroTech Center’ in Brooklyn. Calls were, and remain, received at MetroTech, entered into ca computer, and appear on a computer monitor in the appropriate Patrol Zone dispatcher’s monitor. Radio calls are then made to the RMPs.

In 2011, MetroTech and the computerized 9-1-1 call and dispatch system received an overhaul. Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced: “New York City has sought to overhaul its 911 system for decades,” said Mayor Bloomberg. “Since the system was created in the 1960s, callers to 911 had to, in effect, ask for help three different times at three different call centers that had no automated way to share data and work together. We now have all of the City’s emergency response agencies in one place and on the same system, with state-of-the-art technology that can handle the large number of calls we see during big emergencies. The changes we have made have eluded many administrations and the project has been a challenge, but we have never shied away from the tough decisions or taking on the difficult projects that will make New Yorkers safer and the City work better, and we never will.”

As the MX’s matured and a more flexible design was required, the Motorola SABER was introduced. Instead of discrete channel elements used in previous models the MX was “synthesized” and could be programmed on a computer. Twelve channel and multichannel models were developed and used until the early 2000’s when the Saber was discontinued.

A small number of General Electric MPS portables were purchased for use in Temporary Headquarters Vehicles (THV) and was, the first truly synthesized portables used by the Department.

The Department now uses a truly universal portable that is capable of being programmed for all of their channels. A new specification was made and the only company that came close was VERTEX with their VX-530 model. The VX-530 was eventually replaced by the VX-537 and now every Cop who graduates from the Police Academy is issued a personal VX-537 which remains with him/her until it has to be replaced. A compact VX-800 was also purchased for Supervisors and Detective Bureau personnel. Today the NYPD has approximately 100 channels in both the Patrol Zones, the new name for Divisions, Specialized Commands as well as other channels.

A recently constructed call center in the Bronx will improve the city’s emergency communication systems and 911 call response times. It is projected that the center will be operation in fiscal year 2016.

In light of the impact and decades of service that Deputy Chief Francis J Burns, Superintendent of the Telegraph Bureau, and the later Communications Bureau, had on the history of communications in the department, perhaps his name should be considered if/when a name is chosen for the new center.

“What’s the Deal:” With the History of Police Communications in New York City? Part 3, Post WWII Two-Way Radio Communications, covered the infancy of two-way radio communications which were the result of technology brought about by the war effort. The technological advances, and incremental steps adopted by the department in the early years, and decades, were important as they resulted in changes in the very way the department policed. The number of foot patrols decreased as the number of two-man RMPs increased. This resulted in a change in the dynamics, and relationships, between citizens and their officers, but also offered more efficient services.

The invention of transistors resulted in less expensive, smaller, and more widely distributed use of radios by a growing number of officers. In the following years, the technology gained grounds much faster than in the early years covered in this Part. and the use of the 9-1-1 system, in 1969, again changed the way the department operated and communicated. As the technology advanced, radios became smaller and less expensive and the department required new space for the ever-changing computerized call receiving and dispatching centers.

This Part did not cover many of the more recent technologies such as License Plate Readers, digital cameras, handheld computers, and so on as information on the technologies over the past three decades is readily available online.

Acknowledgements and Image Sources

This article was written in collaboration with Mike DiPalma who also provided many of the images used. Mr. DiPalma has five decades of experience in radio communications and is extremely knowledgable about the radio operations of the NYC PD. Additional images came from a variety of sources, including SPR-3100 Magazine, Annual Reports of the PDNY, The Author’s archives from a now closed Facebook group, and the authors’ collections.

The authors welcome constructive criticism, corrections, additional information, and photos that may enhance the article! Simply fill out the “Contact Us’ form on this site and we will respond promptly.

Errata: the c. 1947 Plymouth RMP depicted in this Part was previously, incorrectly, identified as a c. 1932 in part 2. Thanks to the input of one of our fans who advised us “Car is clearly a 1946-48 Plymouth coupe,” we have made the correction.

![]()

Interested in reading lt. Whalen’s book: You can buy it here: NYPD’s First Fifty Years by Whalen & Whalen

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.