![]()

If you would like, before proceeding to read Part 3, click here to read Part 1 and Part 2 of this three Part essay!

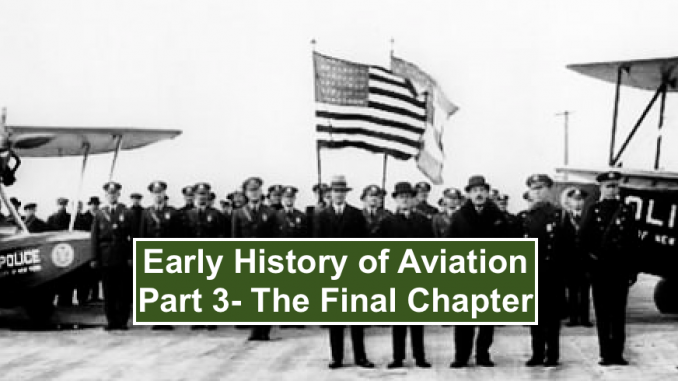

The Post-War (1919) Era; National Defense Scaled Back; Aviation Takes Off

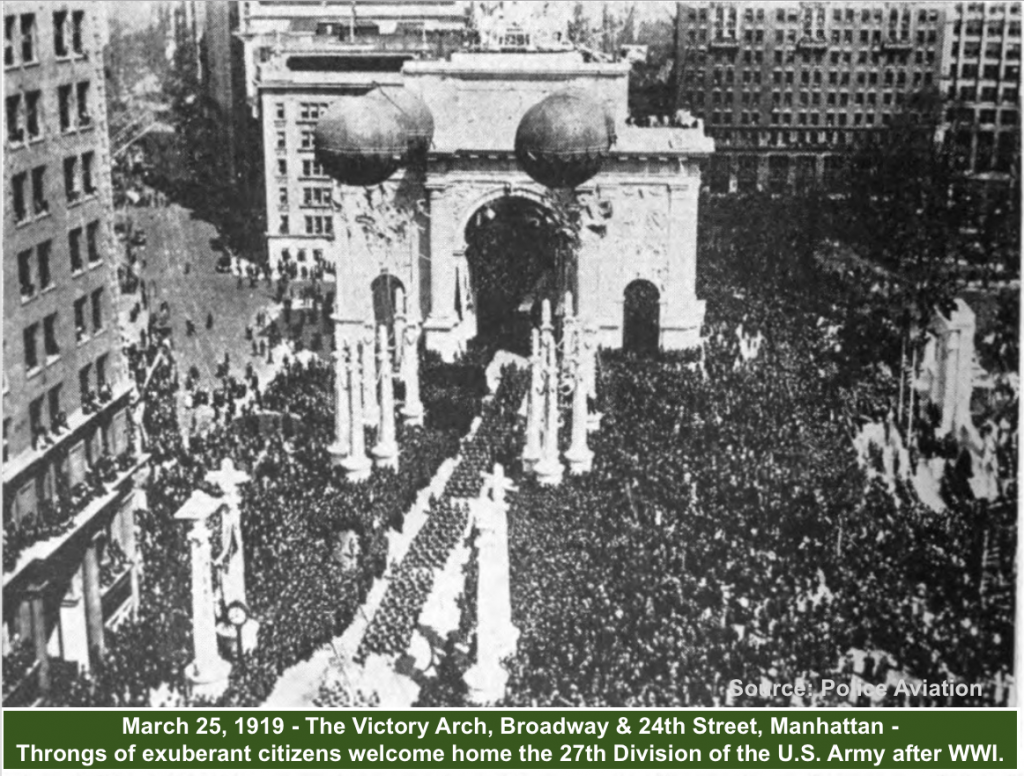

Armistice was declared on November 11, 1918, and the “boys over there” slowly began to arrive back at home. Many of the troop ships arrived in the port of New York to large, welcoming crowds. Parades celebrated their honor, and the Police Department of the City of New York (PDNY) scaled back their Division of National Defense, which included all the Police Reserve units, including the Aviation Section. At the same time, thanks to the advancements in airplane technology, the expanding economy, and the public’s demand for air travel, government officials rose to meet the challenge of dealing with civilian airplanes in their sky.

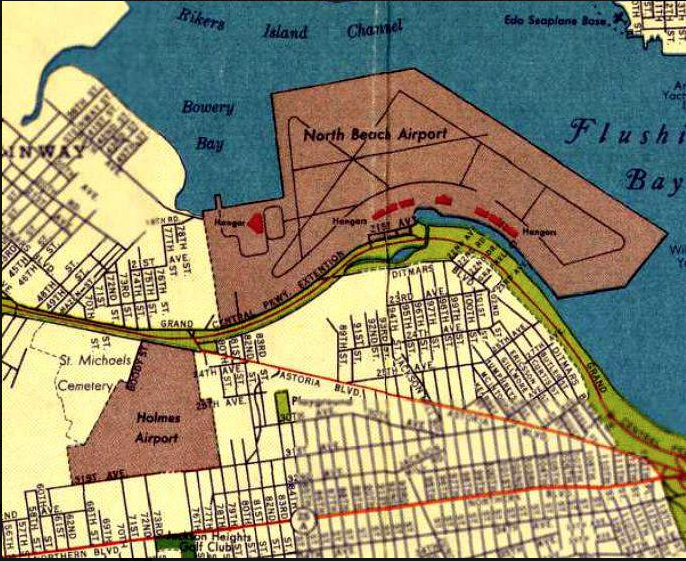

As early as July 1919, the New York City (NYC) Comptroller favored a proposal made by the federal government to the NYC Board of Estimate for the creation of an airplane landing field within the city. The first airport in NYC opened with great fanfare on June 19, 1920. Located on a filled-in strip of the Hudson River at 81st Street, Manhattan, the airport was projected to be the official gateway into the United States of America (USA), with service to and from Albany, Boston, and Washington, DC. NYC Mayor John F. Hylan presided over the ceremony which included exhibitions of various types of planes, dirigibles and a naval armada. The PDNY’s Reserve aviators participated in ceremonies and flew above to the delight of the crowd. Mayor Hylan projected that all docks built in the city, as well as on the rooftops of buildings, would contain landing areas for planes, all of which would be policed by the Aviation Section of the PDNY.

Caption: June 19, 1919 – Located on a filled-in strip of the

Hudson River at 81st St., Manhattan

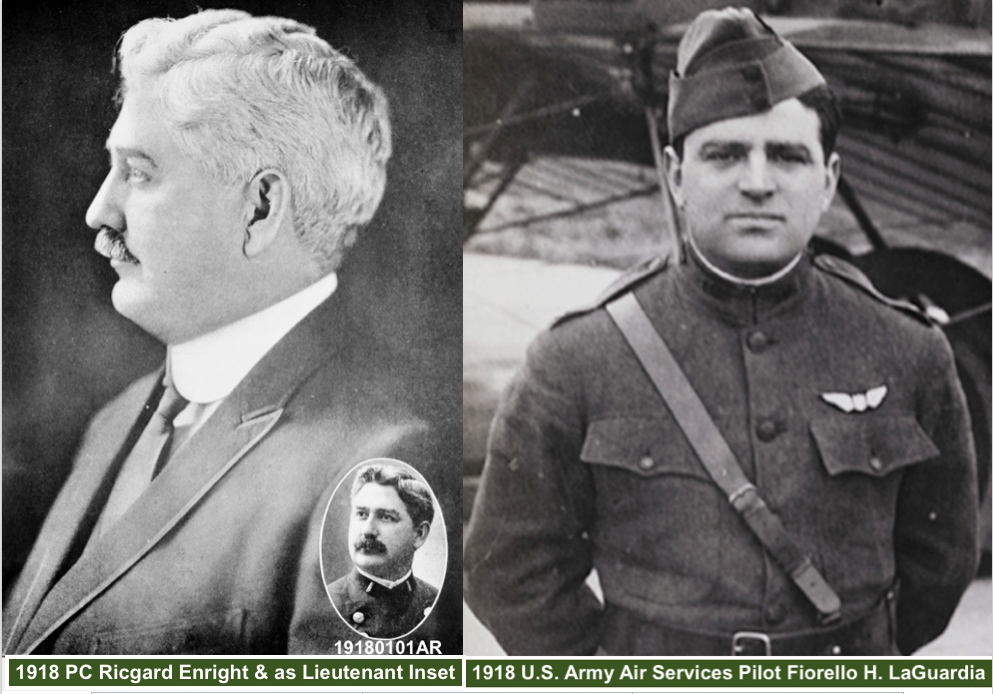

Four months later, on October 23, 1920, a second airport for the Aviation Service of the PDNY was established in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, on the Shore Road Extension, opposite Fort Hamilton, Brooklyn. Mayor Hylan, Police Commissioner (PC) Richard E. Enright (1918-1925) and (SDC) Wanamaker officiated along with Fiorello H. LaGuardia. Mr. LaGuardia, a veteran flying ace of the Great War as a Major in the U.S. Army Air Service, was present in his capacity as President of the Board of Alderman (today’s Speaker of the City Council). Fort Hamilton remains an active field for the New York Police Department’s (NYPD) Aviation Unit to this day.

According to the Annual Report of the Police Department of the City of New York (ARPDNYC) for 1920, the “Aviation Division is comprised of a number of former Army and Navy fliers, aeroplane mechanics commissioned officers of the Reserve and Reserve cadets.” The report added that the division operated from two “flying stations;” one on North River, Manhattan, the other at Fort Hamilton, and that the fleet consisted of “two sea-planes, two aeroplanes and two flying stations.”

Additionally, the report disclosed that SDC Wanamaker donated medals for “meritorious and efficient service” to members of the Police Reserves. The three levels of recognition included: Silver Victory Medals (10), Bronze Victory Medals (65) and Bronze Merit Medals (65). The report further indicated that the city set aside the following sites for aerial police landing places: 130th Street and the Hudson River, Manhattan; Dyker Beach Park, Brooklyn; and 82nd Street and the North River, Manhattan.

In the same month, a published report provided insight into the Aviation Division. The division, due to a stated lack of funds and equipment (planes), was absorbed into two other bodies. The NYC Police Reserve Aviation Division was taken into the U.S. Naval Reserve Force of New York State. While members retained their status in the Police Reserves, they became part of the federal defenses. The regular (career) police officers of the Aviation Division were absorbed into the Fifth Division, Sixth Battalion of the U.S. Naval Reserves. The report detailed that four hydroplanes of the Division were loaned by the Navy while other aeroplanes used by the Division were owned by Reservists.

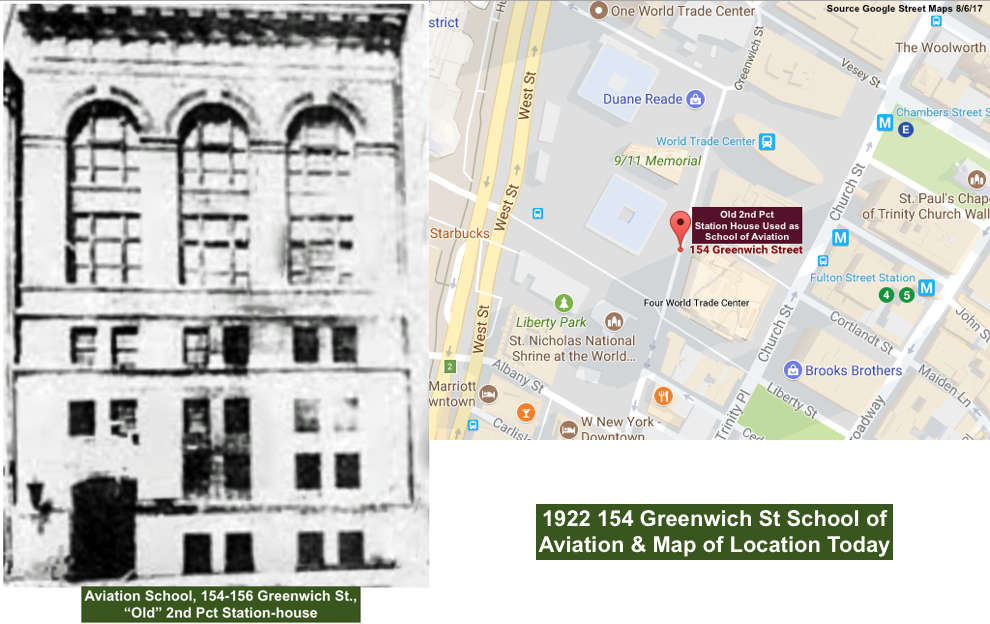

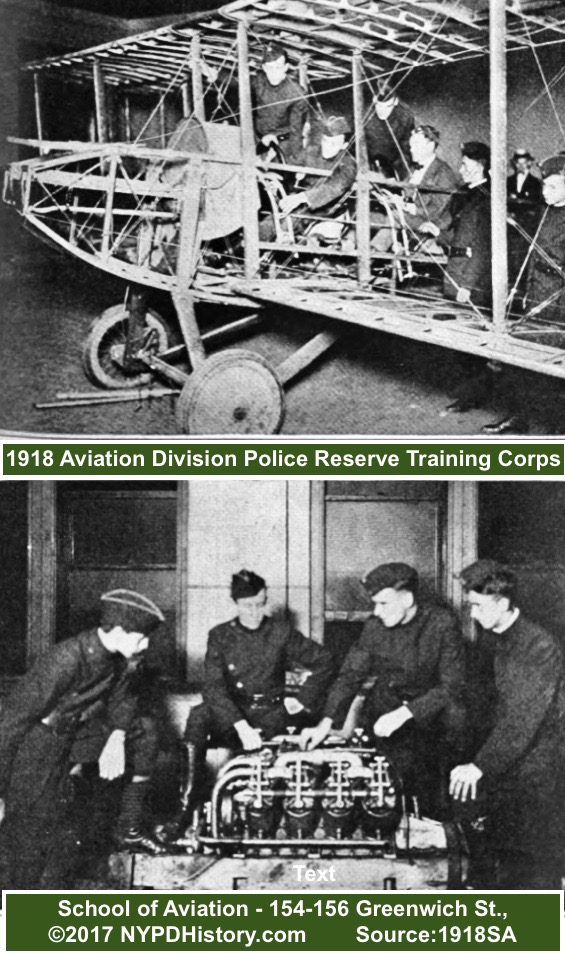

In April 1922, Col. LaGuardia, in his capacity as the C.O. of the Aviation Division Reservists, addressed the PDNY’s use of radios on their aeroplanes. Col. LaGuardia commanded 102 officers (flight and engineers) as well as 160 cadets. The article indicated that the curriculum at the Aviation Training School, 156 Greenwich St., included: telephony, meteorology, radio telegraphy, piloting, and the mechanics of gasoline engines as well as other topics. In describing the training in the use of two-way radios, the article indicated that classes taught cadets to send and receive information using an “international radio code.”

In July 1922, PC Enright issued a warning through Inspector (Insp.) Dwyer to all civilian aviators that violations of recently adopted city ordinances relating to flight, would be subject to arrest at the peril of the use of force, if necessary. Examples of some of the ordinances included: flying too low, performing aeronautical stunts over populated areas, and landing at unapproved sites. Police Captains (Capt.) were instructed to report all violations of these ordinances to Headquarters which would dispatch a “patrolman of the aviation reserve to take air and pursue the violator.” In an interesting example of asset sharing, one officer from the PDNY was assigned to fly with New Jersey police-aviators, and vice-versa, in the event that a violator landed in another state. In light of the above, PC Enright decided to activate the Aviation Division Reservists.

The first full day of air patrol took place on Saturday, July 22, 1922, and included the active patrol of the air with three Curtiss planes, police marine (boat) units on the water, and police spotters on land. The aviators were armed with machine guns which were to be used only in cases “of extreme necessity.”

In the ARPDNYC for 1923, PC Enright, in addressing the traffic crisis in Manhattan, speculated that “It is not entirely unreasonable…to suppose that the aeroplane, or some contrivance resembling or based on it, will eventually come to our rescue and reduce street traffic, not alone the congestion, to the vanishing point. PC Enright’s prophecy, or dream, has not yet been realized but perhaps is nearing a reality which of course would lead to congestion in the skies.

In January 1924, a lecture on the use of radios was presented to 200 men of the Police Reserve Aviation Section by an engineer of the Western Electric Company. PC Enright announced that he sought funding to equip the seven airplanes, located at Fort Hamilton, with radios at a cost of $15,000.

In August 1924, Inspector General Charles H. McKinney was in charge of the Aviation Section. The bounds of the area of patrol included Fort Hamilton, Sandy Hook (NJ), Staten Island, and Norton’s Point, Massachusetts. Practical training (actually piloting aircraft) was strengthened from two to four planes on weekends. Admiral Charles Peshall Plunkett, U.S. Navy provided the four planes, as well as a Naval Reserve Instructor.

According to the ARPDNYC for 1924, the Aviation Division, comprised of eighty-five officers and men, had two non-Department owned seaplanes, and hangars at “Police Park.” Police Park adjoined Fort Hamilton and used by the Police Reserves as training grounds and headquarters. The report further indicated that a class in radio and radio-telegraphy, which began in 1923, had 110 student (officers) enrolled.

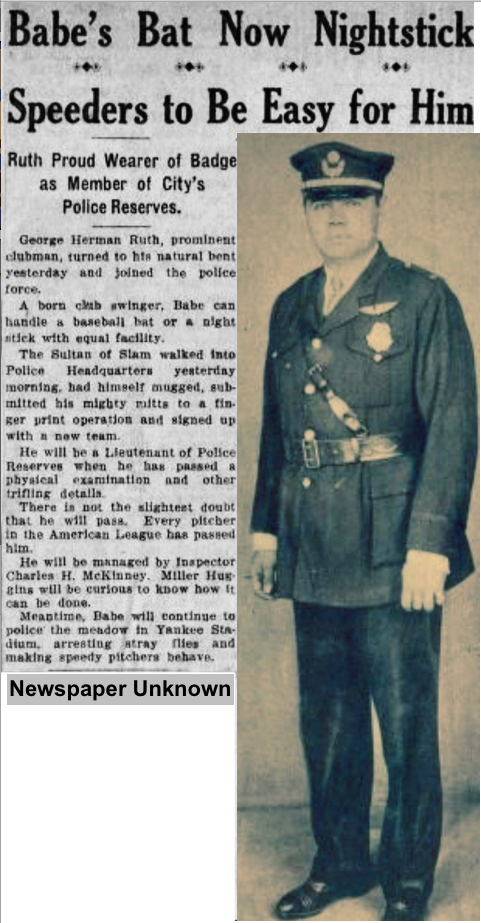

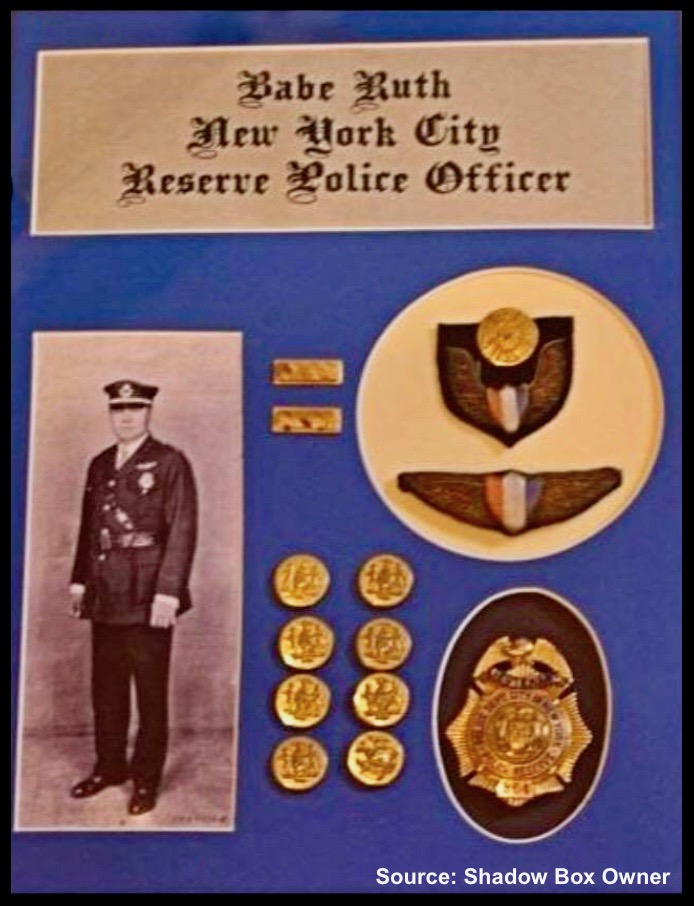

On September 25, 1925, “George Herman Ruth, a prominent clubman, turned his natural bent yesterday and joined the police force.” More accurately, Ruth presented himself at police headquarters where he was fingerprinted, photographed, and processed into the Aero Squadron of the Police Reserves as a Lieutenant (Lt.) and assigned to “Headquarters Staff.” According to an article published on September 25, 1925 in the New York Times, Ruth had been fingerprinted once before “three years ago when he was put in jail for a day – commuted to four hours – for his second conviction for speeding.” Lt. Ruth was assigned to “promote athletics in the Department” and there is no record of his having actively participated in any activities related to aviation.

By the end of the third decade of the twentieth century (1920s), airplanes became more commonplace and remained largely unregulated. Their presence above congested NYC as well as several crashes, such as the one below on Coney Island Beach caused alarm for citizens and calls which resulted in an intervention. The city government and the police administration realized the need for change because the existing arrangement of part-time reserve aviators was not meeting the needs of the ever-growing activity of civil aviation.

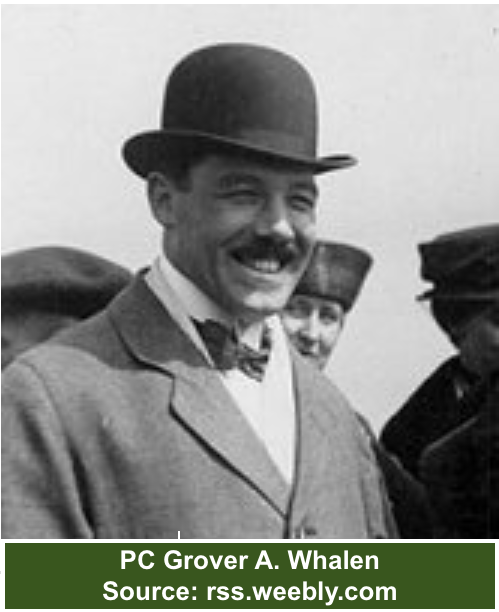

Several incidents where the PDNY was unable to ascertain the ownership of aircraft led PC Grover A. Whalen (1928-1930) on September 9, 1929, to announce that he would seek to appropriate funds in the following year’s budget “to establish a small flying school for policemen, the purchase of suitable aircraft, and the establishment of a department within the Police Department to regulate air traffic over the city.”

September 26, 1929 – “The First Police Air Service in the World;” “First” Again?; The Air Services Division 1.0

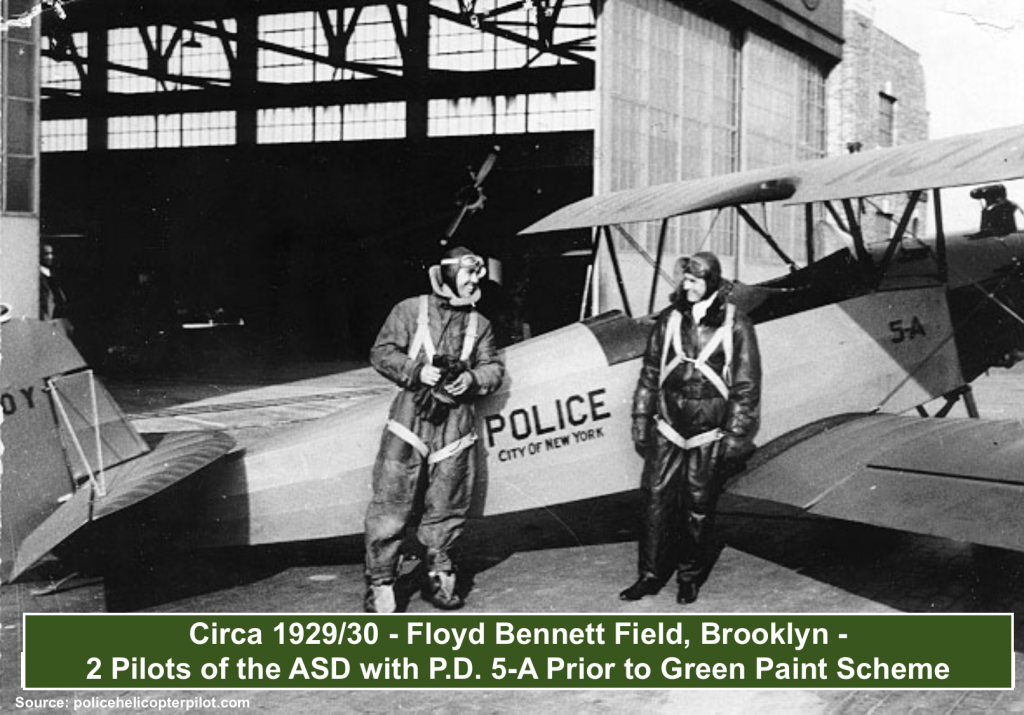

According to the ARPDNYC for 1929, nine plane crashes injured twenty-one persons and killed seven in 1929. The report indicated that the “Air Service Division” (ASD) “was established on September 26, 1929,” by PC Grover A. Whalen (December 1928 – May 1930) to protect the city from reckless and incompetent “flyers.” PC Whalen proclaimed the ASD of to be “the first police air service in the world.” The ASD’s mission was to protect the lives and property of the citizens of the city from all dangers from the air.

The following appears to be the first use of an airplane by the PDNY to transport a prisoner back to the City. On October 4, 1929, Lt. Arthur W. Wallander, Sr., Pilot George Cobb, Detectives T. Malone, W. Mulhany, and G. McCarthy, departed from North Beach Airfield, and flew to New London, Connecticut. There they took custody of a man wanted for murder and transported him back to the city.

On October 23, 1929, PC Whalen announced to the press the creation the ASD and the names of the nine men assigned to the division. PC Whalen added that he secured private funds for the purchase of three airplanes with hope that within one month, the nine officers, all of whom had prior flying experience, would be active. PC Whalen announced that the selected officers began training at the Roosevelt Field Flying School, Mineola, Long Island (LI). All nine men passed the requisite physical examination for student pilots as prescribed by the U.S. Department of Commerce.

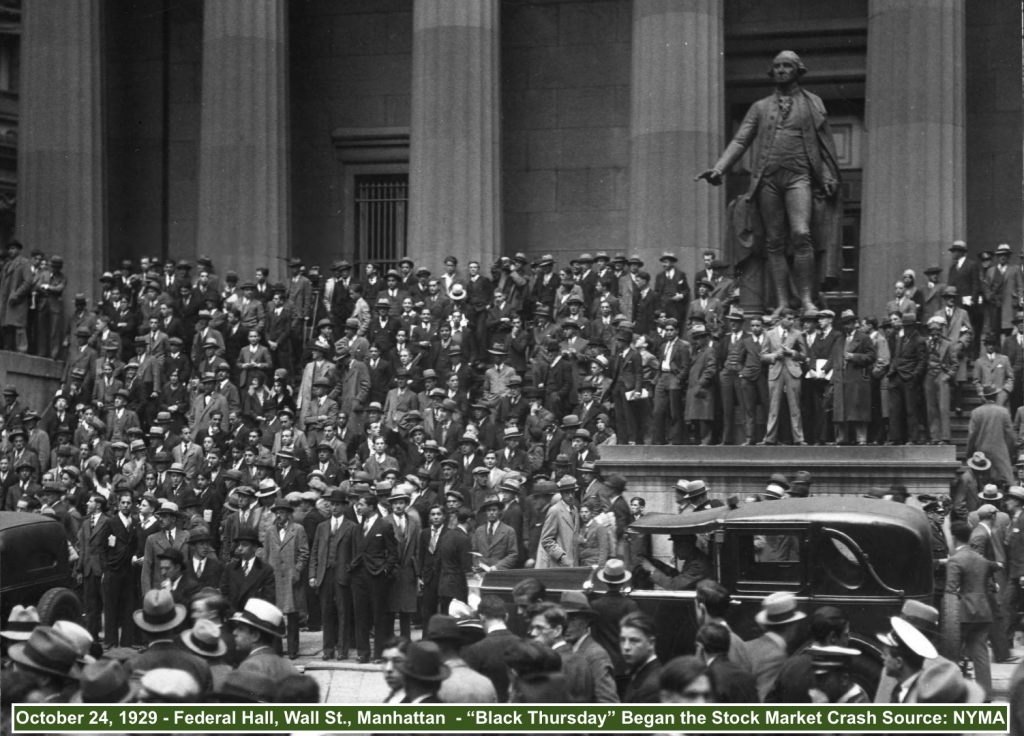

On the same day as PC Whalen announced the “first Police Air Service” in the world, the crash of the stock market occurred (referred to historically as “Black Thursday”) and foretold the future demise of the ASD. In November, another group of five officers arranged training at the Curtiss-Wright Flying School, Valley Stream, LI. Concurrent with the two classes of pilot training, a class comprising twenty-five Patrolmen took place at the “Roosevelt Aviation Mechanics School,” located at 119 West 57th Street, Manhattan.

On January 7, 1930, three of nine Patrolmen-aviators passed the Department of Commerce’s flight and written examinations and became the PDNY’s “first” licensed pilots. (Note: As covered in Part 1 of this multi-part essay, Patrolman Charles F. Murphy, a career member of the PDNY, obtained his pilot’s license in 1914, and flew a non- owned aircraft at official PDNY-sponsored exhibitions. LINK to PART 1 (Ptl. Charles Murphy below in 1914)

In addition to the actual flight training by the pilots, the Roosevelt Flying School agreed to train 300 members of the in the observation of airplanes, while in flight, to identify violations of flight regulations. This was accomplished by having the students observe planes in flight while an instructor, using a loudspeaker, informed them of the correct, and improper, methods of flying. The goal was to educate officers to observe planes and report violations to the ASD.

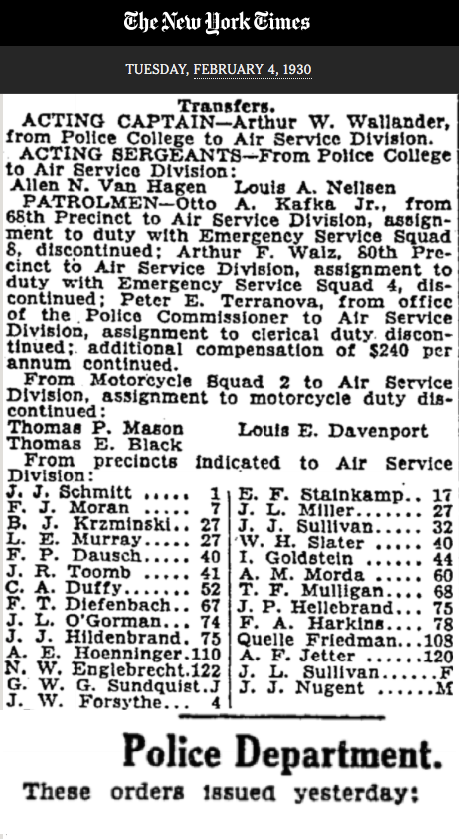

Initially, the ASD was staffed with an acting Captain, three acting Sergeants, twenty-four mechanics and twelve pilots, all of whom were full-time, “regular,” police officers. Three squads were created, each with pilots, and assigned to work day tours. The combination of the men formed the core of the new ASD.

According to the ARPDNYC for 1929, the “aim of the School of Aviation is to inculate (sic) in members of the Force assigned to the Air Services Division a thorough knowledge of the principles and mechanics of the engine and aeroplane and the art of avigation.” (sic) The two-fold responsibilities of the ASD were “to safeguard from all dangers from the air, the law abiding citizen, whether he is flying or using the streets in the City” and “To protect the citizens’ property, whether it be in the form of an airship or a home.” The training course included a “Ground School” and a “School of Aviation.” Candidates for the School of Aviation’s (part of the Police College) Pilot Training “must be young men under thirty years of age, vigorous and healthy, and must possess to an unusual degree, intelligence, alertness, aptitude, decisiveness, resourcefulness, retentiveness and coordination.”

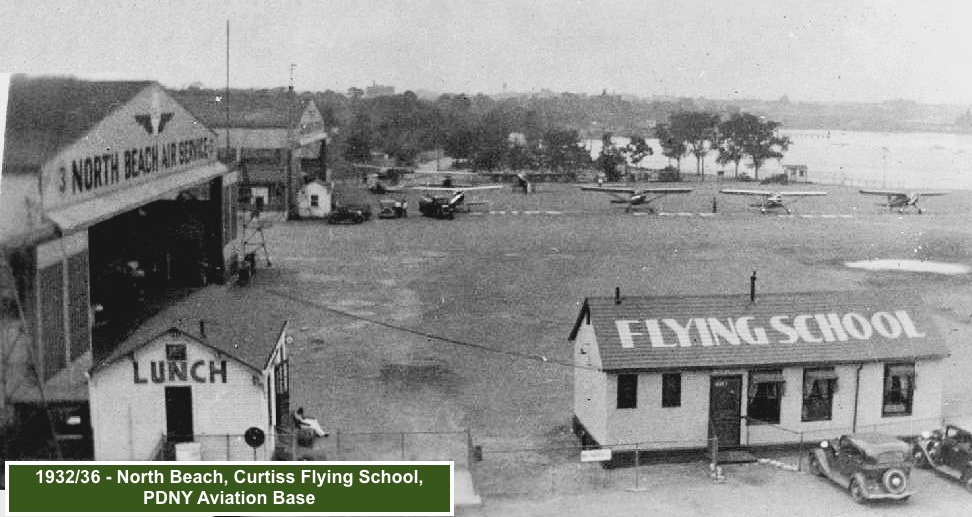

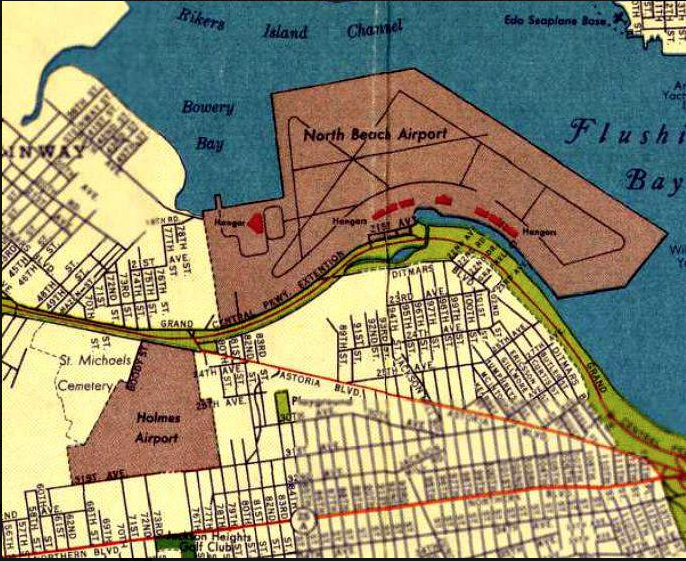

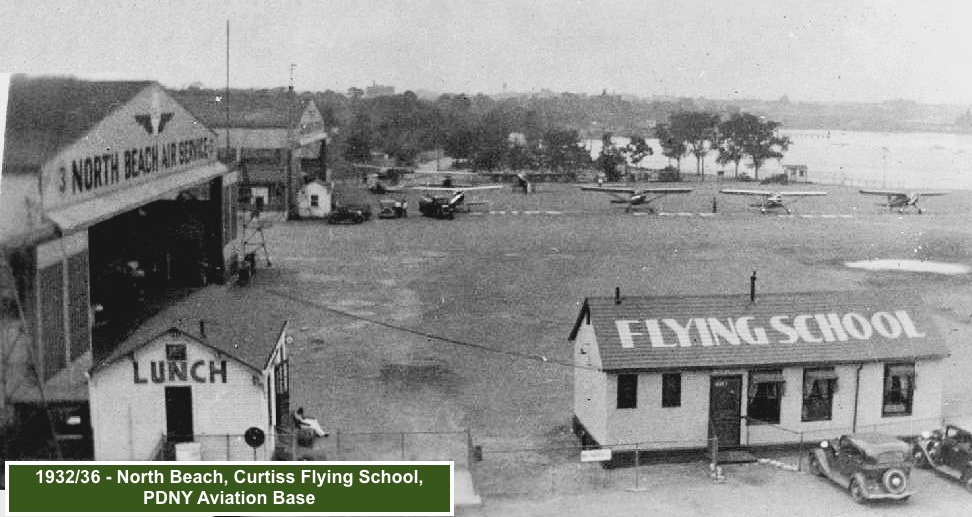

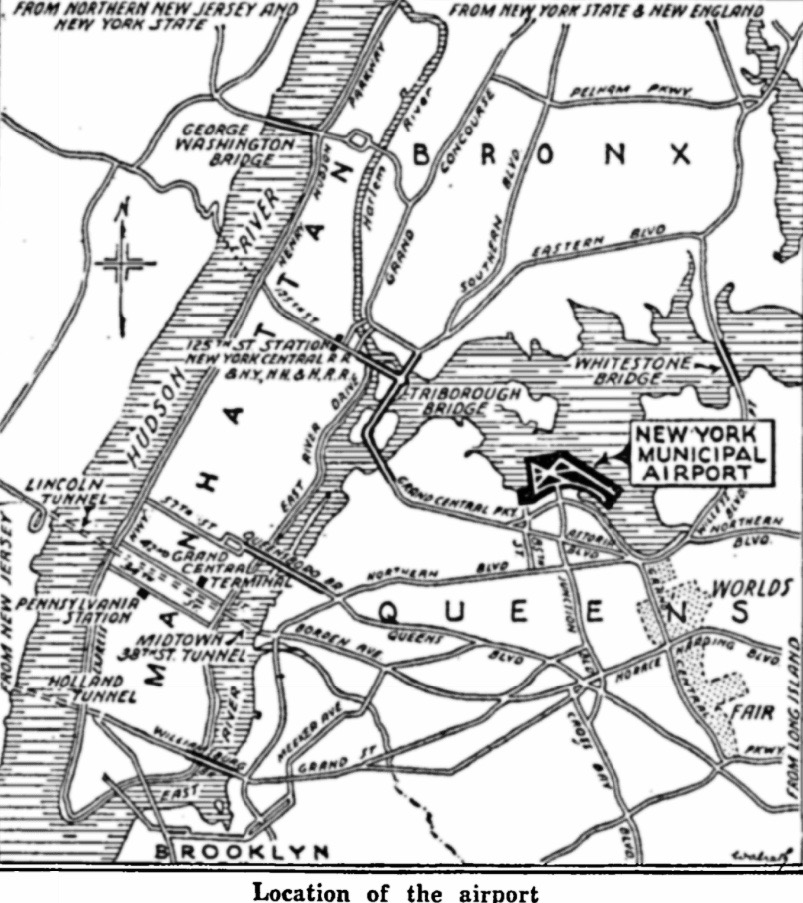

The re-born unit, on the heels of several incidents of recklessness by pilots flying over NYC, moved quickly to establish itself. A PDNY General Order, effective February 1, 1930, made the assignments of those officers who were temporarily assigned to the ASD permanent. The ASD operated out of the Glenn Curtiss Airport, North Beach, Queens, near the present site of LaGuardia Airport. Officially dedicated and opened on March 28, 1930, this field served as the division’s headquarters and training field.

October 31, 1929 – The End of an Era; The Aviation Division of the Police Reserves is Dissolved

On October 31, 1929, the Police Reserve Officers of the PDNY, “by resolution…commended the Police Commissioner for organizing a Police Air Force and turned over $44,000, the balance of in the Police Reserve Equipment Fund, for the purchase of police airplanes. SDC Wanamaker, donated $20,000 for this same purpose.” SDC Wanamaker, initially served as the “Aviation Aide to the Commissioner,” but served in the PDNY into the 1950s.

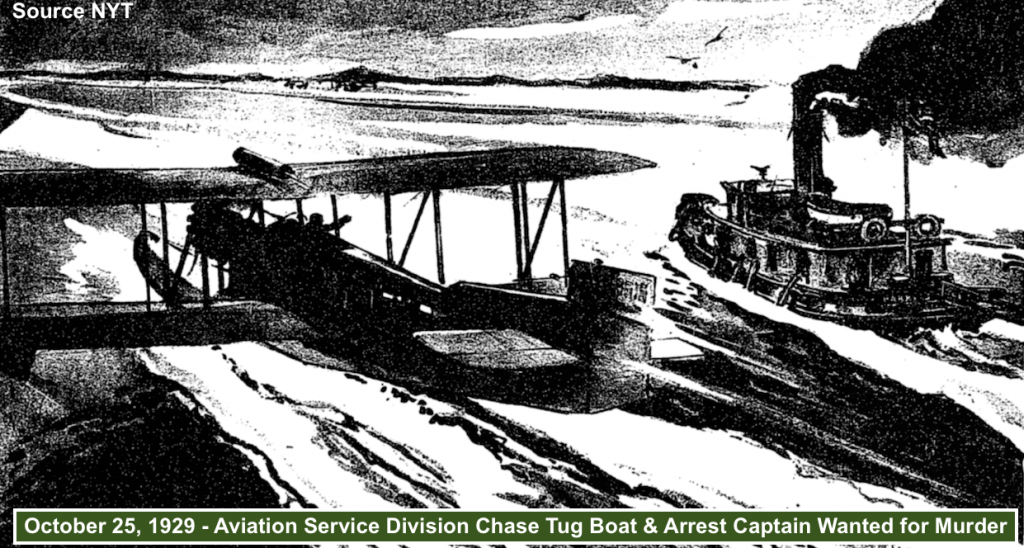

One of the ASD’s first assignments, and another precedent setting arrest, took place weeks after the activation of the unit. On October 5, 1929, the mission (search and arrest) resulted in the arrest of tug boat Capt. William G. Baker, who was wanted for murder. The incident involved a fist fight between Baker and Capt. William Mehaffey, a barge Captain for the Lehigh and Wilkes-Barre Coal Company. The incident occurred aboard Mehaffey’s vessel while docked at Fort Schuyler, Bronx. This “first” differs from the of the October 4, 1929 flight in that this marked the first use of an airplane for the “pursuit and transportation” of a person “sought by law enforcement.” The October 1929 flight transported a prisoner already in custody.

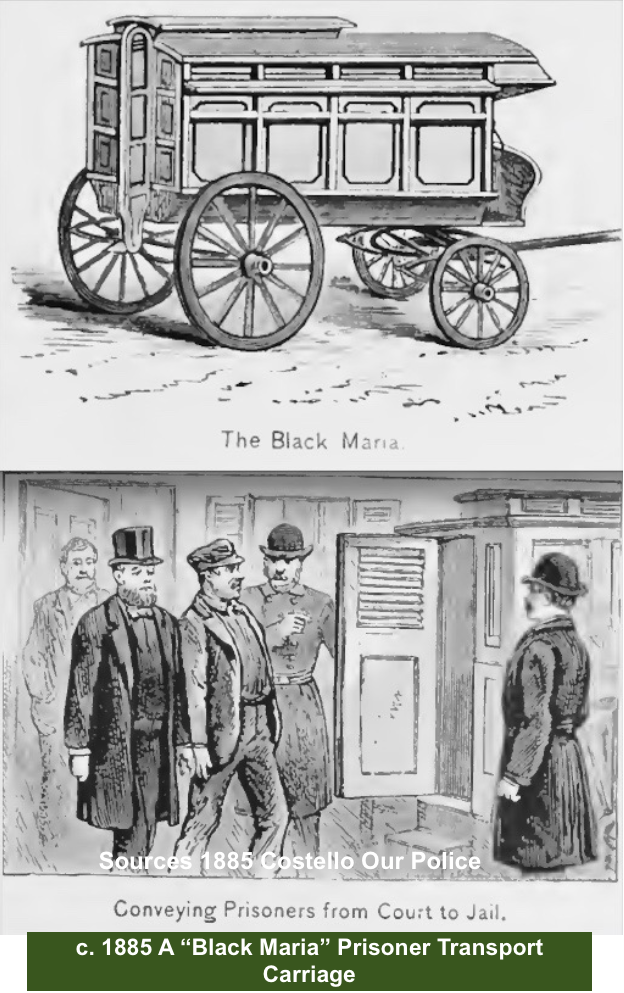

Several uniformed officers using the Loening amphibious airplane (which may have been privately-owned), searched for the tug boat “Harry S. Keeler” in the Long Island Sound. The pilot and officers located the vessel off of the coast of Cape Cod, landed the plane near the boat, arrested the captain, and flew him back to the North Beach (Queens) airfield, in what was dubbed “the Black Maria of the air.” The nineteenth century term “Black Maria” described the prisoner wagons that transported prisoners to and from the City’s jail, courts and prison.

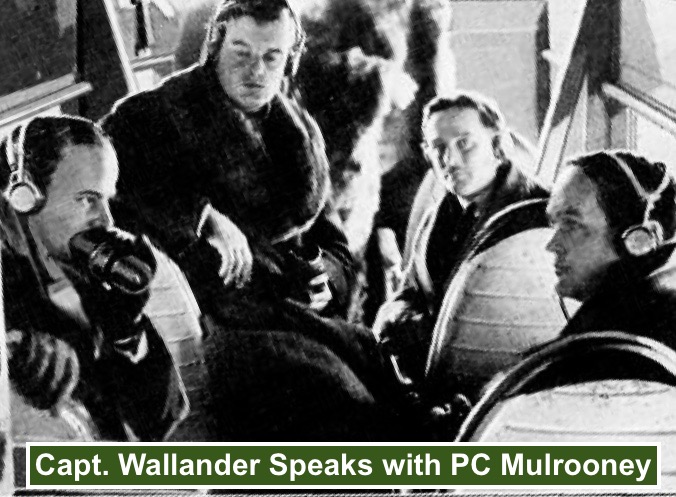

The four officers involved in the first arrest of its kind were Deputy Chief Inspector Edward P. Mulrooney, Lt. Arthur Wallander, Detective (Det.) George McCartney (Bomb Squad) and Arthur Chamberlin (PC Whalen’s Secretary who was appointed “Assistant for Aviation”). Chamberlin, an aviator in the Great War, was appointed by PC Whalen to oversee the air service of the Department.

PC Whalen led a welcoming party at North Beach and announced North Beach as his choice for the proposed aviation police, which was to consist of two to three amphibious aircrafts. PC Whalen also stated that he hoped that the selection of personnel, from an applicant pool of more than 100 officers of the Department, would result in the commencement of training early in the following year.

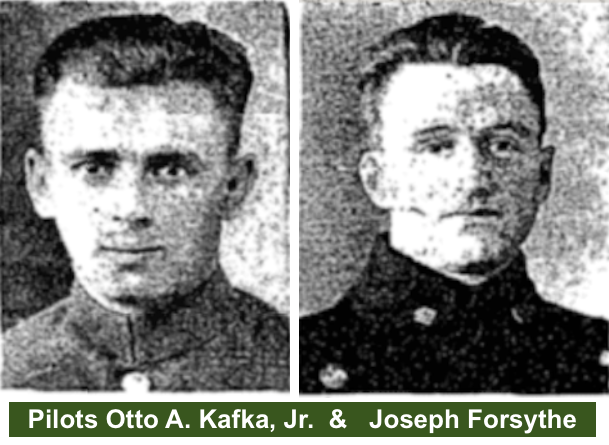

The first crash of an unoccupied aircraft owned by the PDNY took place on November 23, 1929 when Patrolman (Ptl.) Otto A. Kafka, Jr. was on a training flight. A New York Times article, published on the same date, describes Ptl. Kafka as one of PC Whalen’s “embryo flying police” and one of the department’s best flying students. Having successfully landed his training plane in Hicksville, LI, he was “a little overzealous in starting the motor with the throttle too wide open” and the plane taxied over him, across a field, and crashed into the ground, damaging one wing and the propeller. In what must have been a long ride, filled with anxiety, Ptl. Kafka got a ride back to Roosevelt Field where he reported his misfortune to SDC Wanamaker.

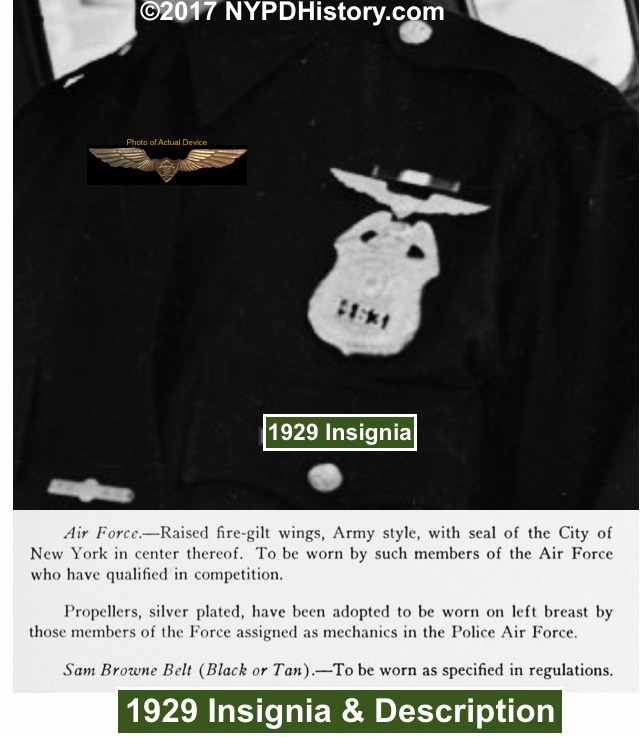

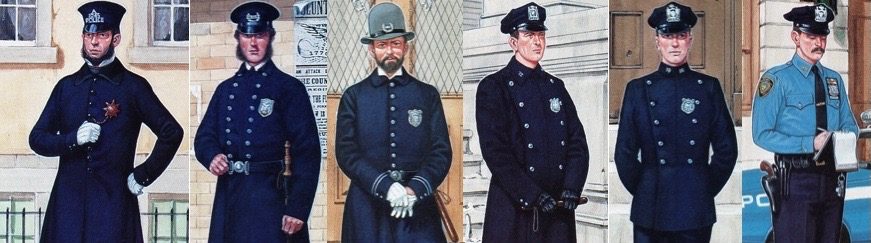

On December 17, 1929, at the Keystone-Loening Plant located at the East River and Thirty-first Street, Manhattan, at 10:00 am, PC Whalen, SDC Wanamaker, along with all of the members of the aviation unit (twelve pilots and twenty-five mechanics) wearing “their smart new khaki uniforms,” took delivery of a Keystone-Loening Commuter amphibious airplane. In 1929, for the first time since 1912, the department changed the style of uniforms. The ASD’s uniform took on a distinctive look with the addition of the “Sam Browne Belt” which were colored brown or tan and aviation-related emblems. These belts were also worn by ranking officers of the department.

At the conclusion of a brief ceremony, the plane flew to Roosevelt Field where it remained as a training aircraft. A luncheon followed at SDC Wanamaker’s home located at 12 Washington Square North, Manhattan. Mr. Chamberlin, in the presence of PC Whalen, Capt. Rickenbacker, and others, announced that funds were being sought for the purchase of at least four planes. PC Whalen provided examples of recent incidents which demonstrated the need, stating “Already criminals are beginning to use the air. Our police picked up two Chinese wanted in Boston in connection with a murder who escaped that city in a plane and landed here. When Auburn prison a few days ago called for gas bombs in a hurry we sent them up by plane.” Capt. Rickenbacker predicted that “every great city would follow New York’s lead.” Here again these words echo those of Ptl. Charles M. Murphy (1914).

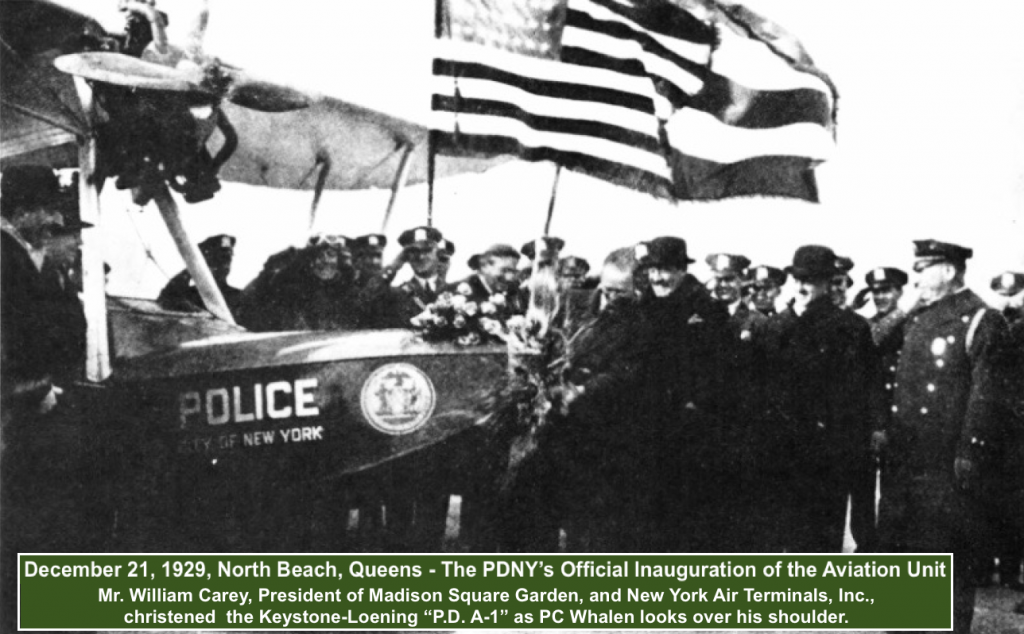

The official dedication of “Roosevelt Field” (airport) took place on December 21, 1929 with great fanfare. Attending were, amongst the police officers of the ASD, and others, PC Whalen, Chief Inspector (today’s rank of Chief of Department) John O’Brien, and Capt. Wallander. Five days later, on December 21, 1929, as the Police Band played “In the Good Old Summertime,” and “while icy winds whistled through the flying wires (of the airplanes) and two bottles of ‘christening fluid’ crashed over the ice-covered prows (noses) of the flying-boats,” PC Whalen took delivery of one of three initial planes of the new fleet of airplanes. Employees of the aircraft manufacturer flew the planes to the “New York Air Terminal at North Beach” from the municipal airport on Barren Island, Jamaica Bay, Brooklyn. (Note: In 1926, landfill was used to connect Barren Island with Brooklyn to create Floyd Bennett Field.)

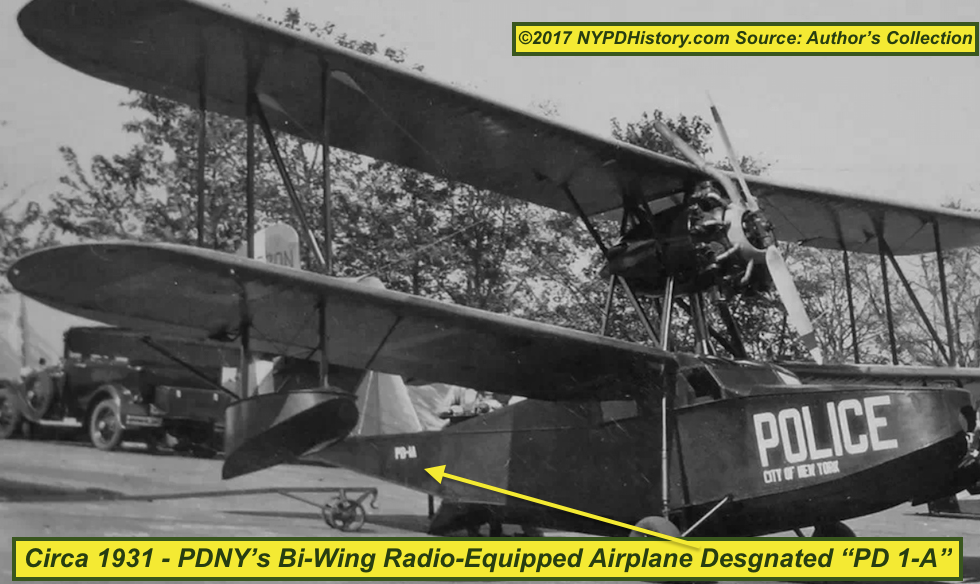

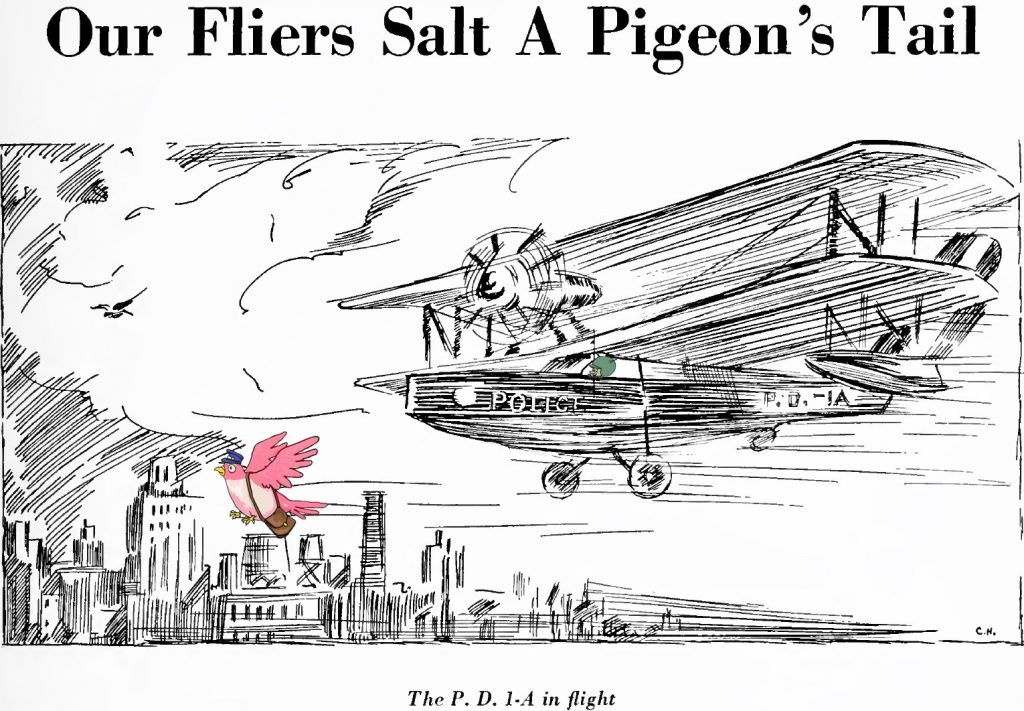

Mr. William Carey, President of Madison Square Garden, and New York Air Terminals, Inc., christened the Keystone-Loening “P.D. A-1.” Clarence D. Chamberlin, christened the Savoia “P.D. A-2.”

This fleet consisted of two single-engine Savoia-Marchetti S-56 “flying boats” which were built in Port Richmond, LI and one Fleet brand bi-plane. The ARPDNYC for 1929 indicated that “A Loening Commuter Amphibian four-passenger plane and three-passenger Savoia-Marchetti Amphibian planes were purchased…christened “P.D. 1-A” and “P.D. 2-A” and placed in service December 21, 1929.” (Note: the difference in the planes’ designations in this and the previous paragraph are quoted accurately as reported.)

The following is a list of the men transferred from their existing commands to the Air Service Division, effective February 3, 1930:

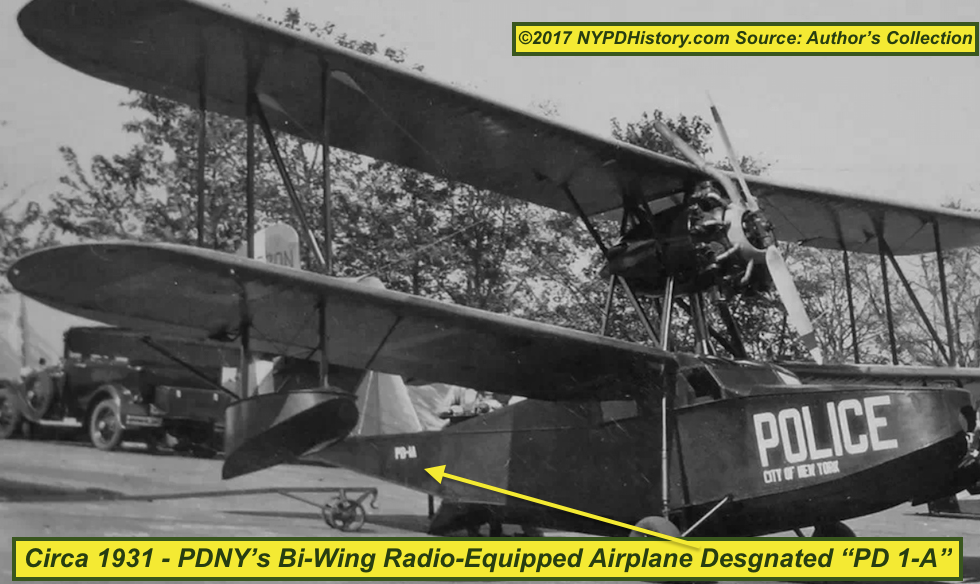

The first day that the ASD went “on regular patrol duty over New York City” was Saturday, March 29, 1930. Increasing the fleet to four planes, two additional Savoia-Marchetti planes joined P.D. 1-A and P.D. 2-A at the new air station at North Beach. The entire fleet of four planes flew above the airfield in “precise military formation” and landed in the East River, taxiing up a ramp where they were met by PC Whalen, SDC Wanamaker, Acting Capt. Wallander, and others.

The new planes were christened as the Police Band played. PC Whalen made a brief address and, sounding much like the prophetic Ptl. Murphy (of 1914), stated “The establishment if such a branch as the air unit is in keeping with the policy of the department to be one day ahead of the criminal element. As we envision the future there is no doubt of the service to which this air patrol will be put. It does not require any stretch of the imagination to believe that criminals will soon make use of the air. The Police Department must be active and progressive. We are ahead of them. We are prepared.”

The plan for patrols were that the three Savoia-Marchettis would be on daily patrol, with the larger Keystone-Loening held in reserve at the air station. Patrolling with a crew for only one hour, the planes returned to the air station for inspection and service and then taken out for another one hour flight by a different crew. It was anticipated that during the summer, weather permitting, the patrol would begin at 7:00 am and end at 9:00 pm. A small building at the North Beach air station was equipped with a department teletype terminal, telephones, and a radio base station.

In April 1930, pilot Huber Waller, employed by the Curtiss-Wright Flying Service, while flying above NYC, caught the attention of Ptl. Peter Terranova of the ASD. Waller became the first pilot to be charged for “low flying” by the ASD. The violation occurred above a large crowd in Van Cortlandt Park, the Bronx.

On April 3, 1930, the “flying squad” marked their “first contact with local flying activities” when Acting-Captain Wallander reported that PD-4A, piloted by Patrolmen Joseph Schmidt and Charles Duffy assisted a stranded seaplane that was forced to land near Riker’s Island after it ran out of gasoline.

In an article, published on April 13, 1930, the New York Times, reported that the four planes of the ASD encountered “an extreme lack of aerial activity” and largely saw only each other flying while on patrol. The article indicated that there were approximately 10,000 airplanes in the USA; that there were approximately 900 planes in NYC; that the local planes largely confined flying above airports; and that there were few flights into and out of the confines of NYC that the ASD needed to monitor. Additionally, it was noted, that with the exception of a few unscheduled flights, there were only ten commercial flights passing over NYC on any given day. The article concluded with a projection that the lack of activity would give the pilots of the ASD time to acquaint themselves with their aircrafts and the environs that they protected and that it was expected that air traffic would soon grow in the vicinity.

On May 7, 1930, the ASD, while on patrol, rescued a seaman from drowning, marking “the first time a life had been saved in this manner by the” ASD. ASD Pilot Ptl. Thomas Mason and Co-Pilot Ptl. Francis F. Diefenbach observed Peter Johnson, age 24, in a tender (small boat) as he fell into the East River which resulted from the wake of a passing boat. Landing the amphibious aircraft near the drowning man, Ptl. Dieffenbach pulled Mason aboard and transported him to Hart’s Island (Long Island Sound near City Island).

In yet another “first” for the ASD, on June 4, 1930, Ptl. Diefenbach and Ptl. Albert Ketter, patrolling in one of the Savoia-Marchetti amphibious airplanes, over Flushing Bay, made a hard, forced landing as a result of motor trouble. The crash resulted in Ptl. Diefenbach’s ejection into the waters of the bay. Ptl. Louis Jade. Ptl Jade, of the ’s Marine Unit, was on a police launch (boat) and witnessed the crash and rescued ptl. Diefenbach. The “flying boat” was “badly damaged.” Ptl. Diefenbach was transported to Flushing Hospital for treatment of “submersion” and a broken ankle.

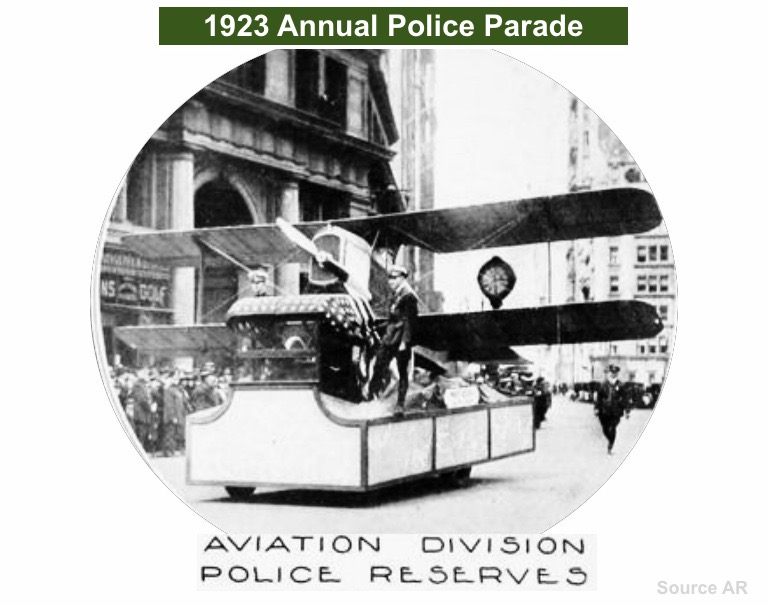

The ASD participated in the annual police parade on April 26, 1930. Included in the parade were 7,000 officers, including officers of the various units of the Department. The ASD exhibited the Division’s three amphibian planes, which were mounted on the chassis of automobiles.

In November 1930, wireless radios had not yet been installed in the ASD’s aircraft. However, on on the 27th of November, PC Edward P. Mulrooney (1930-1933), at his desk at Police Headquarters, communicated for the first time by wireless with an aircraft. Acting Capt. Wallander (then head of the uniformed ASD) and SDC Wanamaker were in separate radio-equipped aircrafts, owned by the Western Electric Company, high above the City.

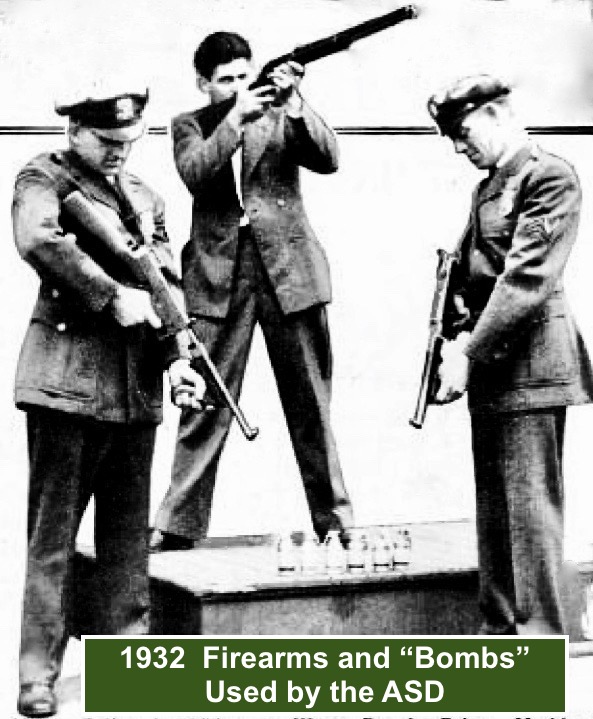

In his statement included in the ARPDNYC for 1930, PC Mulrooney declared that the ASD, in their “first year of the existence” had become an “integral part of the Department performing a variety of missions.” Additionally, the first course of training in the use of firearms specifically for the ASD was conducted. The report indicated that the five aircraft in the fleet were piloted by the twelve pilots a total of 921 hours, on 254 out of 279 days during the year (inception of unit to end of year); that the base was located at the Glenn H. Curtiss Airport, North Beach; and that the patrols had been effective in reducing accidents and violations. Of note is the fact that the first aviation laws enacted by New York State were effective on July 1, 1930.

Much like risk enthusiast Ptl. Charles M. Murphy, Mr. Curtiss ‘ path to becoming an aviation pioneer began with bicycles and motorcycles. His name was not only synonymous with the flying school, flying service, and the airport, but the Curtiss-Wright Corporation that he formed with Orville and Wilbur Wright! The company continues to operate to this day.

Learn More About Curtiss Here

Learn More About the Curtiss-Wright Corp Here

The new “Police Academy” was dedicated on December 21, 1929. Located in the Headquarters Annex building, next to Police Headquarters on Centre St., Manhattan, it housed the School of Aviation. Located on the fourth floor of the Annex, the school provided theoretical (classroom) instruction. Practical instruction and training took place at the Police Air Base, located at Curtiss Airport, North Beach. The Pilot Training Course totaled 200 hours while the Mechanic’s Course totaled 150 hours. Training included the use of handguns and sub-machine guns as well as explosives and other firearms.

In 1930 and 1931, the fleet comprised four amphibious planes (P.D.-1A through P.D.-4A) and one land plane (P.D.-5A). (Note: P.D.-3A was taken out of service in 1930.) In 1931, the ASD’s personnel were reduced in number; pilots from ten to six and mechanics from twenty-one to fourteen.

Option: Before reading on, try to formulate an investigative plan to the following scenario from the March 1931 SPRing 3100 Magazine. The answers will appear below.

On August 31, 1931, in yet another first for the ASD, an airplane was used by law enforcement to track a carrier pigeon in a kidnapping case. Several days after the disappearance of his sixteen year old son, Edgar F. Hazleton, Jr., former Queens County Judge Edgar F. Hazleton received a ransom note attached to a carrier pigeon. The note instructed the judge to tie $1,000 to the legs of the pigeon and to set it free. The judge instead attached a note asking for proof that this son was alive and released the bird. The judge then received a telephone call directing him to go to a candy store at 72-25 Parsons Boulevard, Flushing, Queens, where he found a pigeon in a box with a note advising him not to try to trap the kidnappers. At this point the judge sought help from the police.

Learning of the incident from the case detectives, Insp. John J. Gallagher, coordinated with ASD Pilots Kafka and Van Hagen. Together they devised a plan to track the bird using an airplane. They painted the top of the bird red to facilitate it being seen from above, and after the plane was airborne, the Detectives set the bird free. The plane tracked the bird to a rooftop aviary on a house in Jamaica, Queens. Communicating by hand signals to an officer at a Police Booth at 162nd St. and Queens Boulevard, the door Patrolman ran to a nearby house and awaited instructions. Ptl. Van Hagen landed his plane, drew an “X” on a map where the pigeon landed, and Detectives responded to home at 46-12 161st St., Jamaica, Queens and learned from the homeowner that a man “in a big green car and seemed well to do” rented the pigeon coop. When the man in the big green car returned to the coop, the detectives caught the kidnapper “red-handed.”

Weeks after the story was published nationwide in newspapers the judge’s teenage son, while in Mobile, Alabama read about his own “kidnapping” and travelled by train to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania where he notified the Pennsylvania State Police of his situation. Edgar’s claimed (in a typical teenage manner) that he hitchhiked to Mobile, saw the article, but did not have money to telephone or wire a telegram to his parents, so he took a train to Harrisburg.

The perpetrator, George Marthens, age 48, of 22 Gladiola Ave., Floral Park, LI, confessed to the crime, was convicted and sentenced to five years incarceration at Sing Sing Prison, Ossining, New York. The saying he was sent “up the river” derives from the transportation of prisoners from NYC to Sing Sing, which sits on the shore of the Hudson River.

Answers to the above questions. The answers were published in the April 1931 edition of SPRing 3100.

On December 30, 1931, pursuant to General Order 55, PC Mulrooney presented various forms of recognition for acts of bravery and valor to 308 members of the department. “For the first time in the history of the department, the Air Service Division is recognized in the award of commendation” read the article, published on December 31, 1931, in the New York Times. Ptl. Otto A. Kafka, Jr. of the ASD, and Ptl. George W. G. Sundquist, 63rd Precinct, were awarded Commendations. According to the article, the men “alighted on the waves off West Second Street, Coney Island, last July 15 and rescued a drowning woman.”

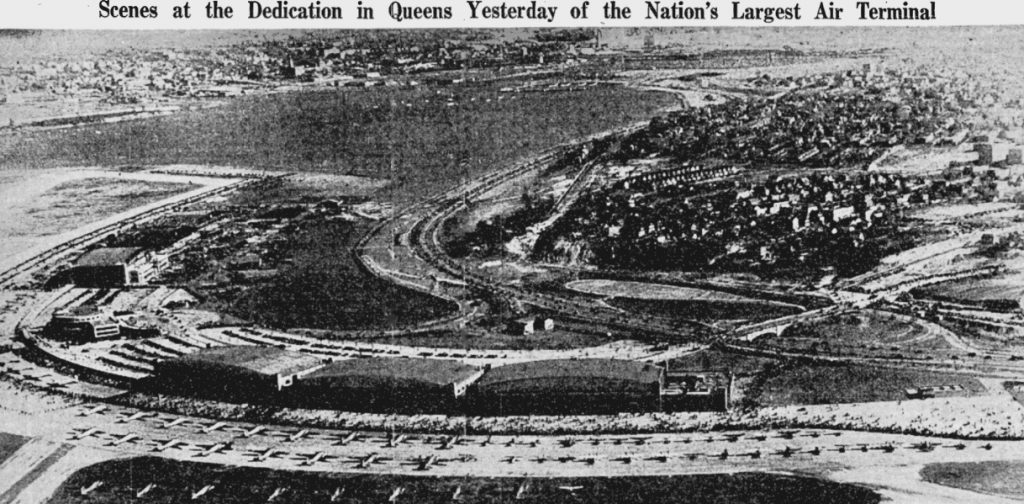

The dedication for the new NYC Municipal Airport, named Floyd Bennett Field, located at the site of today’s LaGuardia Airport, Queens, took place on Saturday, May 23, 1931, and was officiated by Mayor Jimmy Walker (1926-1932). Mrs. Floyd Bennett was present. Mr. Floyd Bennett, a native of New York State, piloted Admiral Byrd to the North Pole in 1926, and upon his return, was welcomed into NYC with a ticker-tape parade. In 1928, Bennett succumbed to pneumonia as a result of rescuing a German aircraft crew stranded on Greenly Island, Canada.

The ASD’s patrols above NYC resulted in a decline in the number of low-flying, and unsafe flying planes. The ASD was tasked with flying officers to retrieve prisoners who were extradited from other states and performed several rescue missions in and around NYC.

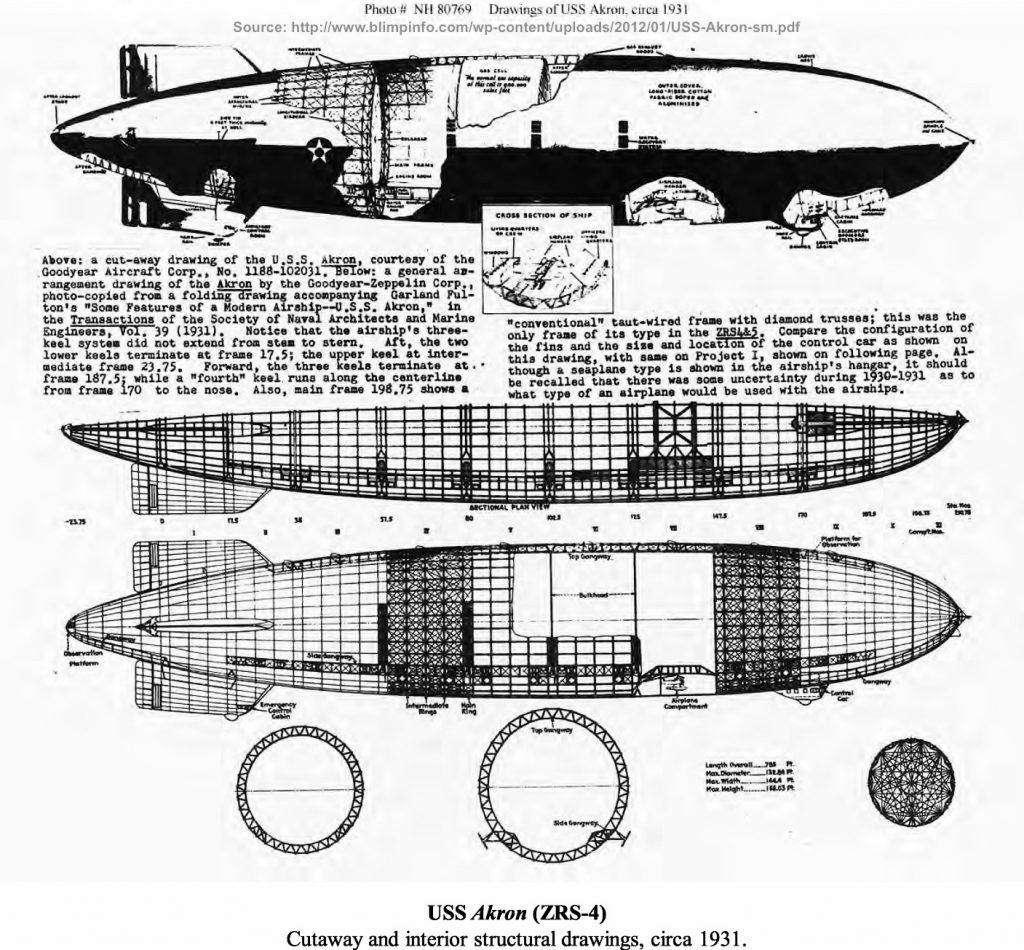

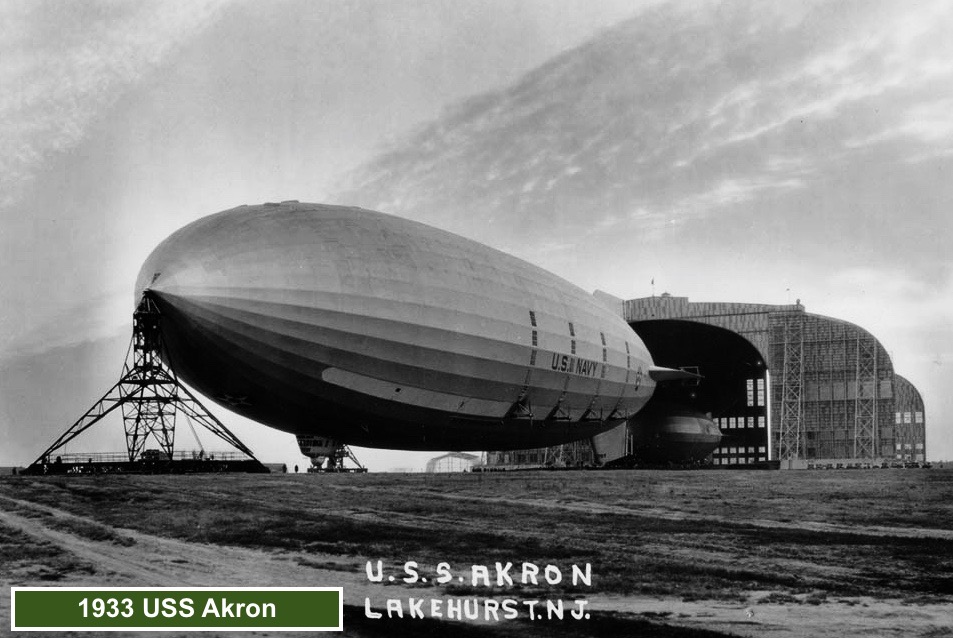

In one notable case, a giant rigid (framed) dirigible, 785 feet long was built in 1931, in the largest hangar in the world, in Akron, Ohio. Christened “Akron,” the dirigible made fifty-eight successful flights crossing the country many times and took on the nickname “Queen of the Skies.” Shortly after midnight on April 4, 1933, the Akron was in flight above the coast of New Jersey, near Atlantic City, when it encountered a violent storm that caused it to crash into the Atlantic Ocean. Of the seventy-six passengers aboard, only three survived. Compounding the tragedy, a non-rigid Navy dirigible searching for survivors of the Akron crash, also crashed, killing an additional two men. An amphibious airplane of the PDNY’s ASD, while searching for the Akron, saw the Navy dirigible J-3 crash and rescued five of the seven surviving airmen off of the coast of Beach Haven, Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Ptl. Otto A. Kafka, Jr. again received recognition from the Department. On July 21, 1933, for their action in the rescue of the airmen of the Navy dirigible J-3, Ptl. Kafka, and Acting Sgt. Joseph W. Forsythe received the highest level of recognition, that of Honorable Mention, making them the first members of the air service of the PDNY to receive the recognition. Ptl. Kafka subsequently rose through the ranks to Captain.

In 1932, the ASD made two notable advances by using aerial photography to document the scene of riots, and by experimenting in the use of radio-telephones to report vehicular traffic conditions to police headquarters.

While not a line of duty death, the untimely death on April 23, 1932 of ASD Sgt. Allen Van Hagen, age thirty-five, of 252-A Hancock St., Brooklyn, must be noted. Sgt. Van Hagen, an eighteen year veteran of the department, off-duty, performed a test flight of a privately-owned, commercial airplane for a friend at the Curtiss-Wright Airport, Valley Stream, LI., when the crash occurred. Sgt. Van Hagen and his friend died from their injuries. A member of the ASD from its inception, Sgt. Van Hagen was the Chief Pilot of the Division. Sgt. Van Hagen joined the Department in 1915, and was previously assigned to Motorcycle Squad 3 prior to being transferred to the ASD on October 24, 1929. Sgt. Hagen was a pilot during WWII.

On July 29, 1933, Ptl. Terranova and Ptl. Richard W. Ryan, an ASD Mechanic-observer, were on aerial patrol above Coney Island, Brooklyn when Ptl. Ryan observed two men in apparent distress some 500 yards offshore. Ptl. Terranova landed his amphibious aircraft on the water, near the swimmers, and Ptl. Ryan threw the men a flotation device. Both men were too exhausted to grab hold of the lifesaving device leading Ptl. Ryan to jump into the ocean and perform a water rescue. Ptl. Ryan grabbed the men and the line attached from the plane to the float and Ptl. Terranova drove the plane to the shore.

For his actions, on April 4, 1933, Ptl. Ryan was awarded the New York Daily News’ monthly award of $100, made to a member of the PDNY or the Fire Department of the City of New York. this marked another “first” for the ASD. In accordance with regulations, the award was presented by PC Ryan, Acting Capt. Wallander (C.O. ASD), and Arthur Chamberlin, “Assistant Secretary to the Police Commissioner in Charge of Aviation.”

March 19, 1934 – “The First Police Air Service in the World;” Downed by The Great Depression

As mentioned earlier, the stock market crash (1931) foretold the demise of the ASD. “Black Thursday’s” stock market crash was one of several factors leading to the Great Depression (1929-1939). Other factors were bank failures, reduced purchasing throughout the economy, the drought in the midwest, and America’s economic policies with Europe.

On March 19, 1934, the ASD “was reduced to skeleton proportions” by PC John F. O’Ryan (January – September 1934). Nine members of the ASD were transferred to the Emergency Services Division (ESD). Three of the nine were Frank Harkins, Otto A. Kafka, Jr. and Peter Terranova. One Sergeant and two Patrolmen were left in the “emergency service of the aviation bureau” and it was reported that the city considered selling some of the fleet of two amphibious airplanes and two biplanes.

In 1934, the PDNY re-designated (re-named) the ASD the “Aviation Bureau.” The department also placed the Aviation Bureau (the bureau) under the command of the ESD. Today, the “Aviation Unit” is under the command of the the Chief of Citywide Operations, along with the re-designated Emergency Services Unit.

On March 12, 1936, the quarters of the Aviation Bureau base, now located at Floyd Bennett Field, Hangar 1, relocated to Hangar 4. In 1937, fifty-seven “mission flights,” sixty-three patrol flights, six response flights to complaints and twenty-one aircraft accident investigations were performed by the bureau. The bureau also had a plane co-located with the Harbor Unit on the East River. This permitted the coordination of both units’ efforts. Safety inspections of aerial advertising banners and adherence to a new city ordinance governing the same were added to the list of the bureau’s responsibilities.

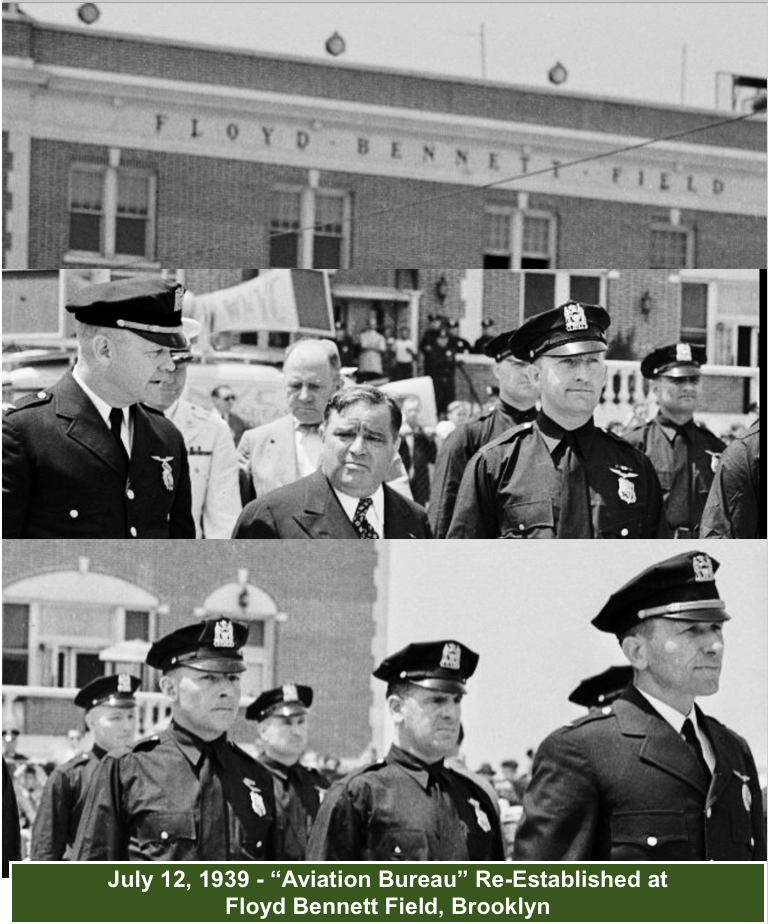

July 12, 1939 – Like the Preverbal Phoenix from the Ashes; “ASD 2.0 Rises as the “Aviation Bureau”

Mayor LaGuardia clearly understood the benefit of the ASD and worked to restore the necessary funds. Mayor LaGuardia, aside from his personal experience with aviation, was a keen politician facing re-election and did not want the blemish of the lack of police aviation to be a campaign issue. According to outstanding book “The NYPD’s First Fifty Years; Politicians, Police Commissioners, & Patrolmen,” by authors Bernard & John Whalen (Available on amazon):

“By the summer of 1939 the city’s financial situation had improved enough to reinstate the division a hanger at Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn and rename it the Aviation Bureau. The department’s new fleet consisted of two ultra-modern 450-horsepower Stinson fixed-wing aircraft purchased with the help of aviator Howard Hughes at a cost of approximately $34,000 each. Each plane could carry up to five passengers, attain a crushing speeds of 160 miles per hour, and maintain two-way radio contact with the ground crew.”

The planes donated by Hughes were two Stinson Reliant SR-10K high-wing monoplanes. One plane was a seaplane (floats) and cost over $14,000, and the other a land plane (wheels) cost over $19,000. The planes were painted in the familiar green with white lettering and would remain in service, with one possible exception, through World War II (WWII), until 1954.

According to the ARPDNY for 1939, in addition to the above aircraft one new Stinson seaplane and one new Stinson landplane were purchased. Both aircraft had two-way radios, and 450 horsepower Wright engines. For the first time, the bureau’s aircraft were equipped as ambulances and navigation equipment that permitted “flying blind” (in the dark, poor visibility). Twelve pilots and six mechanics comprised the bureau. Six of the twelve pilots were licensed by the federal government as two-way radio operators.

Once again, on July 12, 1939, with great fanfare and while the Police Band played “Come, Josephine, in my Flying Machine,” Mayor LaGuardia and PC Lewis J. Valentine (1934-1945) led a ceremony held at at Floyd Bennett Field, Brooklyn, “to mark the re-establishment of the Police Department’s aviation bureau”. Two new Stinson airplanes (registration numbers NC21147 and NC21148) were placed into service. By all accounts this occurred without the expense of broken bottles of champagne.

Mayor LaGuardia and New York Yankees Pitcher Vernon Louis “Lefty” Gomez were passengers in a new plane, piloted by Acting Sgt. Forsythe who took the mayor and his guest on an aerial tour of the city. The fuselage of both planes were painted green, the wings white, and had the words, “New York Police Department” painted in white on their fuselage.

In his speech, Mayor LaGuardia mentioned the forthcoming opening of the city’s first municipal airport at North Beach and used that fact to drive home the importance of the re-establishment of the police aviation service. The mayor thanked famed aviator, and millionaire Mr. Howard Hughes for his continued sport of the PDNY’s aviation services.

Reminiscent of the words spoken before by the mayor and PC Valentine’s predecessors and those of Ptl. Charles M. Murphy, the mayor said “We will find before long that the aviation unit will be performing such valuable and essential work that we will wonder how we got along without it. Of course, some of its work will not be dramatic or spectacular. the punks and racketeers we have around New York are too yellow to fly a plane, and if we take passage on a transport we can head them off by two-way radio.” The Mayor spoke of the need for the aviation bureau to continue its important work in taking aerial photographs of the city as they were used by not only the PDNY, but all of the city’s departments and said it “may seem far-fetched,” but he believed that planes would soon be used in firefighting.

In 1940, the bureau was comprised of six pilots, all of whom were certified two-way radio operators, and six mechanics. In 1942 and 1944, there were nine pilots. The name of the bureau’s airfield, Floyd Bennet Field, was then known as LaGuardia Field.

While during WWII, the unit remained relatively unchanged, historically, war drives invention and accelerates improvements in technology. This was the case with aircraft and, after the end of the war, “war surplus” equipment was sold to municipalities, including more modern aircraft for their police departments.

In 1948, the PDNY benefited from the surplus and purchased a Grumman Goose and Widgeon airplanes. The Mechanics of the bureau completely retrofitted the two planes for use by the bureau. Once placed into service, the planes joined a Stinson Reliant and Bell Helicopter to complete the fleet. From 1947-1950 the bureau had ten pilots, all of whom were veterans of WWII, and seven mechanics.

In 1948, the PDNY’s efforts to codify regulations for flight over the city were realized when, on July 1, 1948, Local Law 55 was passed. This marked the first time that a local governmental body had passed such legislation.

Once the order for the planes was placed, and the unit inaugurated, the PDNY set out to restore manpower. As the Aviation Bureau was now part of the ESD, and many of the former mechanics and pilots were assigned to the ESD, six pilots and twelve mechanics were assigned under the supervision of Insp. Arthur Wallander. In 1938, Insp. Wallander, held the position of Acting-Captain and the C.O. of the old ASD. Insp. Wallander understood the need for the pilots and mechanics to be familiar with the mechanics and operation of the aircraft. Insp. Wallander sent the twelve men to Stinson’s factory in Wayne, Indiana and to the engine’s manufacturer, Wright Aero in Patterson, NJ for familiarization and training. One of the pilots was Ptl. Gustav Crawford, who had been flying since 1929. Crawford rose in rank, became the C.O. of the Air Bureau in 1945 and later became the first to fly a helicopter. In 1950, Capt. Crawford was the C.O. of the 11th Precinct. Wallander served as Police Commissioner from 1945-1949, under Mayors LaGuardia and William O’Dwyer.

The PDNY benefited by acquiring two amphibious planes: a G44 Widgeon in November 1946, and a G21 Goose formerly owned by the British Royal Navy, in 1947. The twin-engine G21 was the last fixed-wing aircraft used by the PDNY. The technology of aircraft improved greatly during and after the war years and the PDNY switched over to helicopters.

In 1946, during wartime, the bureau personnel was comprised of four pilots who were cross-trained as mechanics, an additional pilot, and two mechanics. The bureau performed 168 patrol flights that year, with a fleet of one land plane and one amphibious plane which was grounded during the year.

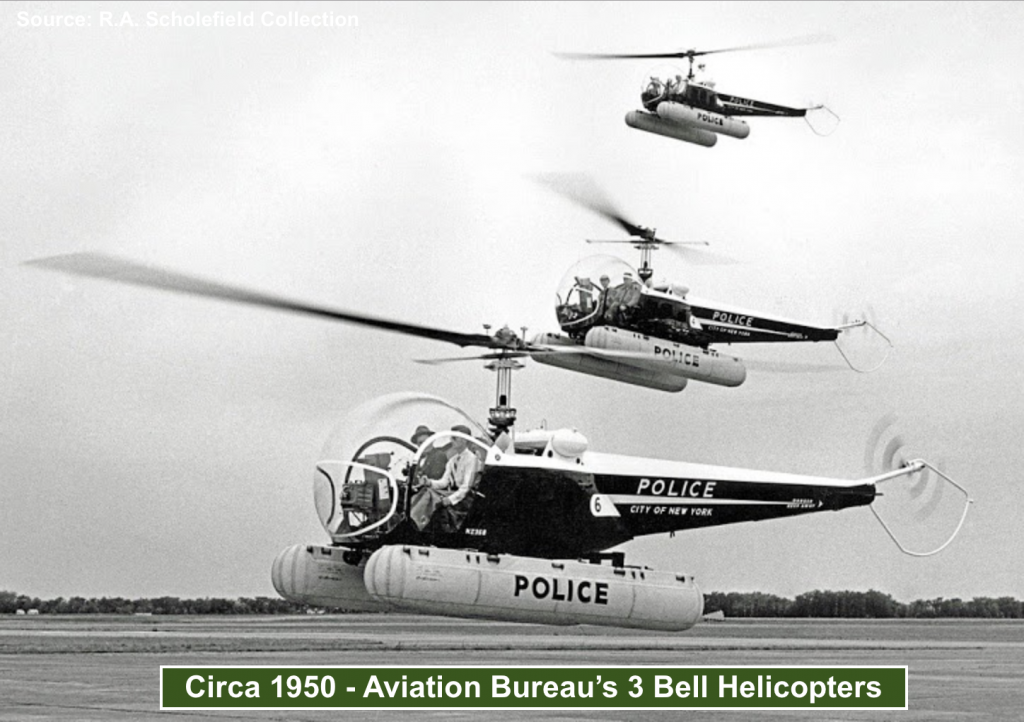

1947 – From Fixed-Wing Airplanes to Helicopters; “The Beat Goes On”

In 1947, the bureau readied to enter a new era; that of the helicopter. The first helicopter purchased by a police department in the USA was purchased in approximately 1947 by the PDNY, and took trial flights for the first time in September 1948. The Bell 47D, tail number NC201B, was stationed at Floyd Bennett Field, then a US Naval installation due to WWII. Equipped with pontoons, the helicopter was amphibious and joined the fleet of three planes at Floyd Bennett Field. In 1949 the bureau had three fixed wing airplanes (one Stinson, two Grumman amphibious) and three Bell helicopters. In 1951, another “first” was noted when a “flight observation patrol car” was added to the bureau.

As was the case when motorcycles, automobiles, and aeroplanes were introduced to the department, few men knew how to operate the new helicopter. The C.O. of the bureau, Gustave Crawford (mentioned earlier) was the first police officer in the PDNY to pilot a helicopter. With some prior experience as a pilot, Crawford joined the PDNY in 1932, joined the Air Bureau in 1939, and was the C.O. in 1945. NYC Mayor William O’Dwyer (1946-1950), a former member of the PDNY, backed C.O. Crawford’s efforts to train more helicopter pilots, expand the unit, and act as a land-sea air rescue option.

C.O. Crawford was trained as a helicopter pilot and instructor by the manufacturer, Bell Aircraft, in 1946 and he trained three bureau pilots to fly the Bell 47Ds. Additional pilots were subsequently trained. The first Bell 47D was replaced in the summer of 1950 by newer models, joining the Grumman fixed wing airplanes which were removed from service in November 1955. At that time, the fixed wings were not replaced and a fleet of six helicopters comprised the fleet.

The helicopters quickly demonstrated their agility and usefulness to the department as well as to the city and ultimately replaced the fixed wing aircraft.

It is at this point that the our well-researched, detailed, and comprehensive coverage of the “early history of police aviation in New York City” ends.

Part 3 – 1918-1950 Re-Cap

“What’s the Deal:” With the early history of police aviation in New York City from 1918 to 1950? WWI drove invention, innovation and the use of fixed wing aircraft. Although not used extensively in battle, the excitement and curiosity of citizens at home (USA) were exuberant over “flying circuses” and aerial exhibitions. The PDNY recognized the fact that it would continue to be relied upon to police the air, aviators and airplanes. Fir the time being, the Police Reserves continued to serve their purpose.

As the end of the decade of the 1920s approached the PDNY recognized the fact that the part-time, volunteer reserves could no longer keep up with the civilian use of aircraft and on October 23, 1929, PC Whalen announced the creation the Air Services Division. On October 31, 1929, the Police Reserve Officers of the PDNY was abolished.

Roosevelt Field served as a base for the ASD, and the Old Second Precinct Station-house in lower Manhattan served as a School of Aviation. In 1930, the ASD was relocated to Glen Curtiss Airport, North Beach.

The ASD performed heroically and satisfactorily and new personnel and aircraft were added to the ASD. The first day that the Air Services Division went “on regular patrol duty over New York City” was March 29, 1930. By 1934, the economic impact of the Great Depression impacted the ASD which lost equipment and manpower. Floyd Bennett Field became the ASD’s home. In 1934, the ASD was re-designated the “Aviation Bureau.” At the same time, the bureau was placed under the command of the Emergency Services Division.

In 1939, with the improvement of the economy, and with the support of the old airman, Mayor LaGuardia, the ASD was re-born. New planes, personnel, equipment and responsibilities were added to the bureau and in the next decade (1940s) and in 1947 the first helicopter was purchased. As the great advantages of amphibious helicopters became obvious, more helicopters were added to the fleet replacing fixed wing aircraft, the last of which was de-commissioned in 1955.

PC Enright was on-point, when in 1923, he addressed how airplanes may solve the traffic congestion in NYC. In the same statement he spoke clearly, and in simple terms to the fact that inventions are often dismissed as being a fad, yet we now live with those inventions every day.

There is no question that the PDNY’s Police Reserves Aero Squadron and Aviation Division are an important and unrecognized part of the history of the NYPD’s Aviation Unit. There are more than a few men without whose connection with the department’s aviation units deserve recognition in some way by today’s Aviation Unit, which continues to service the needs of the city and the department well.

The next, and final installment of this series on aviation will be a summary of “firsts” as well as a list of those men and women whose contributions to the history deserve recognition.

![]()

“Stay tuned” by entering your email address in the box on the top-right of our website. You will receive an email when we publish a new article. It is easy, safe, and confidential, so do it now!

“Like” “Follow” and Share our website and Social Media because “Sharing is Caring!”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.