![]()

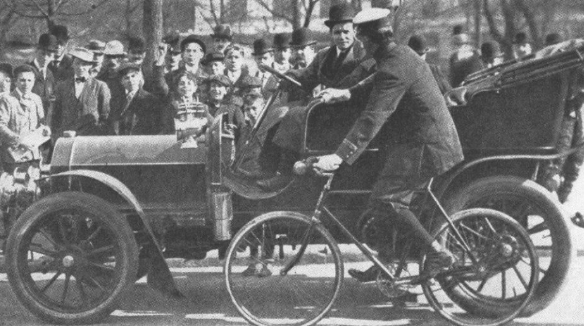

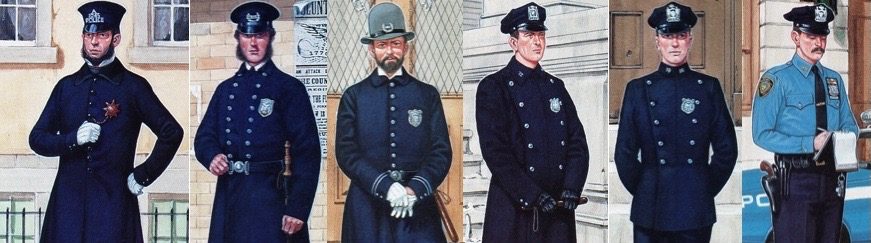

In “Issue 1” of “The Deal,” Police Officers Benjamin Mallam and Eugene Casey from the Police Department of the City of New York’s (PDNY) “Central Office Squad” were introduced. The squad worked out of the “Central Office,” known in the day as “Headquarters” which was located at 300 Mulberry Street in Manhattan. Officers assigned to the squad worked for the the Police Commissioner (PC). In 1905, Mallam and Casey drove PC William McAdoo’s department-owned Panhard-Levassor automobile which they used in the enforcement of speeding, reckless driving and other violations committed by other motorists. This article will address the first, and early, enforcement of automobile traffic laws by the NYPD.

The earliest (“the first”) record found for an arrest for “Reckless Driving” of an automobile appeared in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on May 31, 1896. “At a race between horseless carriages and cyclists yesterday, the horseless carriage, which was managed by Henry Wells, reached One-Hundred and Nineteenth street, on the boulevard” when the car careened out of control and struck a bicyclist knocking him to the ground, breaking his leg, and rendering him unconscious. “The Boulevard” was the former name of Broadway between 59th and 169th Streets. The article went on to relate that “Wells was locked up in the West One Hundred and Twenty-Fifth street Police Station for Reckless driving.”

Three years later, on May 21, 1899, many local and other newspapers carried headlines similar to this one, “Automobile Driver’s Arrest – Said to Be First One Locked Up for Fast Going,” which appeared in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Published on May 21, 1899, this is the earliest information found relating an arrest for speeding and stands as “the first” arrest for speeding in an automobile!

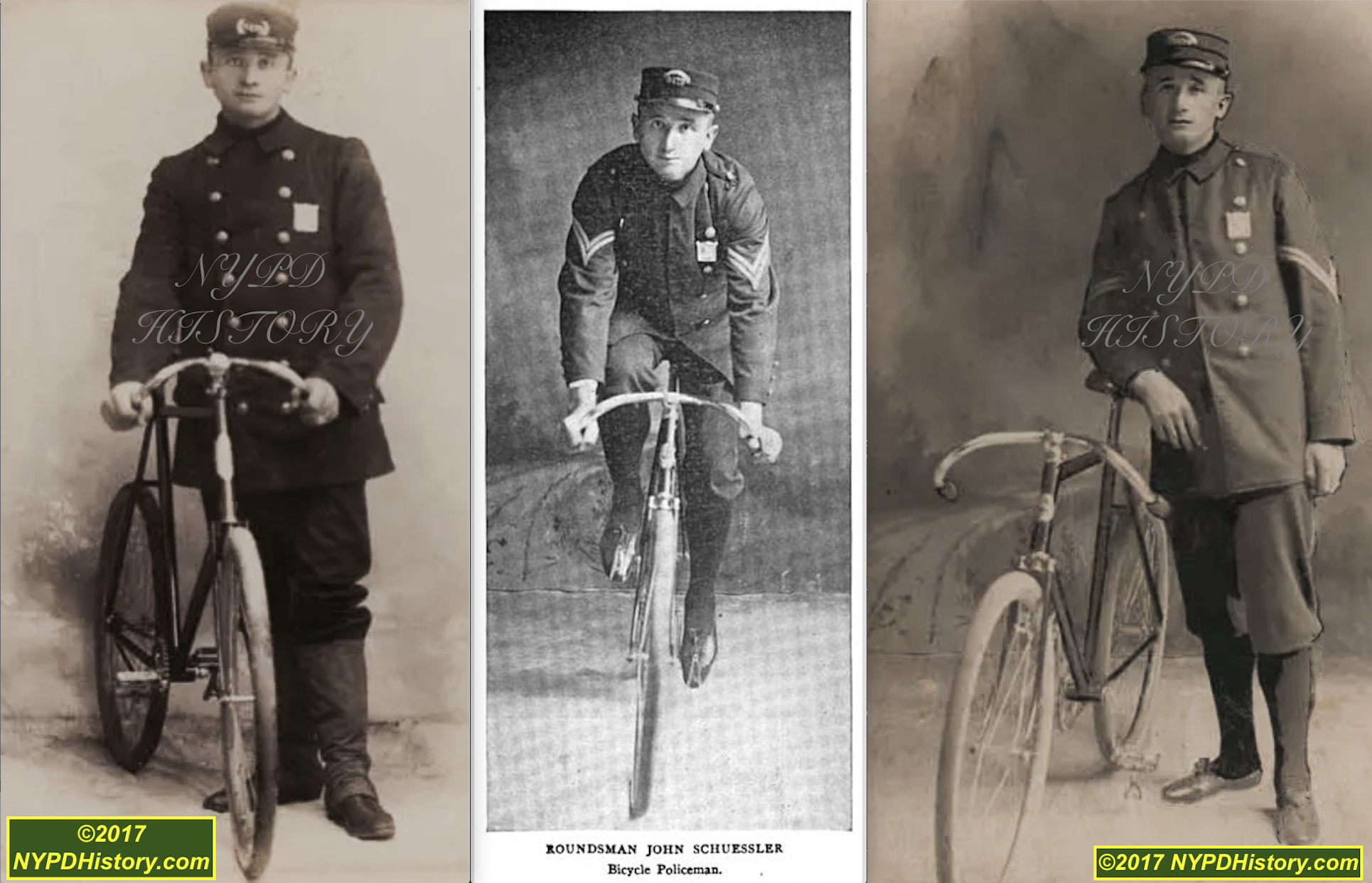

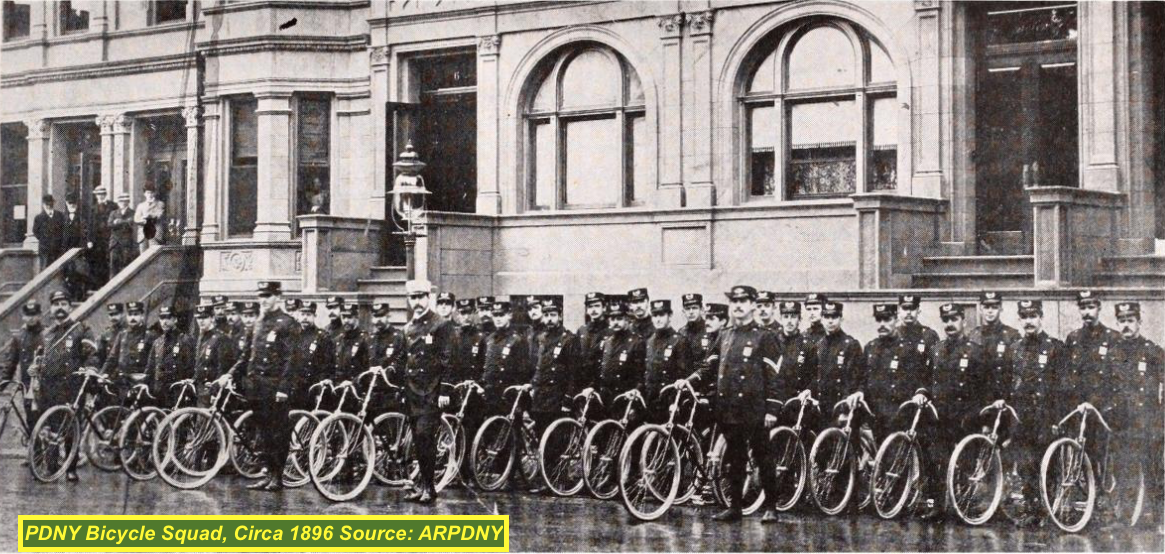

As in the case of the aforementioned arrest for Reckless Driving, summonses were not yet issued in lieu of arrest. In this case, Jacob German, operating a taxi cab for the Electric Vehicle Company of 1683 Broadway in Manhattan, was observed by Roundsman Scheussler (the rank of Roundsman was a predecessor rank to today’s rank of Sergeant) operating his automobile on Lexington Avenue at a rate twice the rate of the citywide speed limit of twelve miles per hour! Roundsman Scheussler, of the PDNY’s “Bicycle Squad,” pursued and caught up to him when he was held up in traffic on Twenty-Third Street. Gorman was brought to the East Twenty-Second Street station. The New York Press’ article of the same date, wrote that German “was dashing down Lexington avenue quite oblivious of everything”…”ringing his bell, dodging in and dodging out, scaring children, and narrowly missing their elders.” (sic)

The drivers of automobiles and other vehicles took liberties when it came to obeying the directions of traffic officers, who stood in the roadways to direct traffic. On June 9, 1900, PDNY Chief of Police, William S. “Big Bill” Devery, issued an order which was to be read to all officers in the PDNY. The order read, in part “You will instruct the members of your command that when a driver…in charge of any…vehicle of any kind refuses to stop such a vehicle promptly when an officer raises his hand as a signal that the vehicle is to be stopped,” the driver “must be arrested.” What the driver was to be charged with was not cited.

Working with the Police Department of the City of New York (PDNY) and the PCs, was an organization, formed in 1898, called the “Automobile Club of America” (ACA), which represented the interests of automobile owners and their drivers (chauffeurs). While the interests of the two entities was sometimes at odds, their combined efforts led to the promulgation of the first set of laws, in 1904, relating to the licensing of drivers, the registration of automobiles, and the first laws relating to vehicle and traffic including automobiles. This is not to say that there were no laws governing the rate of speed, reckless driving, and such prior to 1904. The PD, and courts, interpreted most of the existing traffic laws, known formally as “The Highway Law of New York,” which was enacted in 1890 and amended thereafter by acts of state legislation. These laws pertained to vehicles powered by any source of energy to include automobiles.

In an article entitled “Speed Question in Acute Stage,” published in ACA’s journal, Automobile Topics Illustrated, published on April 19, 1902, introduces the problems and dangers created by speeding automobilists, and the PDNY’s efforts to reign in the reckless while not imposing on the freedom of law-abiding drivers. The article relates that PC John Nelson Partridge “issued a general order intended to bring a strict enforcement of the legal restrictions imposed through the amendments to the highway law passed in 1901,” and other recently passed laws.

Section 167 of The Highway Law of 1901 prescribed that “No person in charge of an automobile or motor vehicle shall drive the same on any public street or place at a greater speed than is reasonable and proper.” Concern was expressed that this clause rendered existing speed limits superfluous and left too much discretion in the hands of individual officers who were not familiar with the laws or speeds. Blaming recent legislation “limiting the rate of speed and providing very drastic penalties” on the “inconsiderate driving” of a few, the ACA reported to its members that they lobbied to “oppose and modify” the legislation which called for a speed limit of eight miles per hour in the city as well as in “unbuilt-up portions of the Greater New York.” While lobbying to modify the speed limit outside of the city, the ACA encouraged its members to abide by the law until it may be changed. The city referred to Manhattan Island and the unbuilt portions referred to the less populated areas of the four other boroughs.

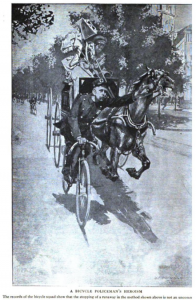

There were several incidents where the appearance of automobiles caused near riots, as they “spooked” horses, causing the dangerous condition called a “runaway” where a single horse or a team of horses with a carriage or wagon attached raced away uncontrollably risking injury or death to anyone in their path. Stopping a runaway horse or team was a dangerous, and often a deadly feat. The responsibility for stopping runaways was usually that of officers who, themselves were mounted on horses or on bicycles. Numerous officers were injured or killed trying to stop runaways. In one such case, a Rochester judge awarded damages to a horse’s owner for the mental trauma caused by a motorist! The ACA also suggested that its members exercise good judgement and courtesies when driving in the public squares to allow horse owners to become “accustomed to the sight of and to the noise made by machines.”

In in article written by the famous Jacob Riis for “The Outlook,” on November 5, 1898, former President of the Board of Police Commissioners, Theodore Roosevelt, who is often credited with coming up with the idea of a Bicycle Squad, commented on the bravery of the Bicycle officers. Roosevelt wrote “The German (likely referring to Roundsman Scheussler) was a man of enormous power, and he was able to stop each of the many runaways he tackled without losing his wheel (bicycle).”

While everyone was becoming more accustomed to the growing number of machines, the state law was again amended on May 3, 1904. According to a New York Times article, dated May 19, 1907, the rate of speed was set “at one mile in six minutes in the heart of a city or town, a mile in four minutes in a suburb, and a mile in three minutes in the open country” leaving the definition of the areas undefined. According to the article, the PDNY had determined that this meant a speed limit of ten miles per hour in Manhattan. The article went on to indicate that the matter of speeding autos was a “catch-as-catch-can” game; that chauffeurs (drivers) routinely gave false information to officers when stopped; that strings were attached to license plates which could be hidden if pursued; and that imitation chauffeur badges were not uncommon (metal badges were issued to drivers in the period).

On May 28, 1904, according to The New York Times, Marcus Seller, Chauffeur to Mayor McClellan, was arrested by Bicycle Squad Police Officer James A. Donohue on Forty-seventh Street for speeding. Mr. Seller explained that the Mayor directed Seller to pick him up at DelMonico’s at 9:30 pm sharp; that he was speeding in order to do so; and that the Mayor had not directed him to speed. Near midnight, Street Department Cleaning Commissioner Woodbury arrived at the West Forty-seventh Street Station-house in order to bail out Seller. The Commissioner told the Desk Officer “Now boys. Let the Mayor down easy. I was arrested myself once for violating the speed limit and the newspapers ran a column about it the next day. Don’t do that with the mayor.” The outcome of the request was not explained, but a follow-up article in the same paper on May 29, 1904, indicated that Seller was fined $10 for speeding at a rate of eighteen miles per hour on Eighth Avenue near Forty-seventh Street.

Present at the hearing was Street Cleaning Commissioner Woodbury who told the Magistrate privately that the Mayor asked for no special treatment of his driver. The Magistrate admonished Seller saying “I’m sorry the law doesn’t permit me to impose a heavier penalty – not in your case particularly, but because the fine seems less than nominal compared with the offense.”

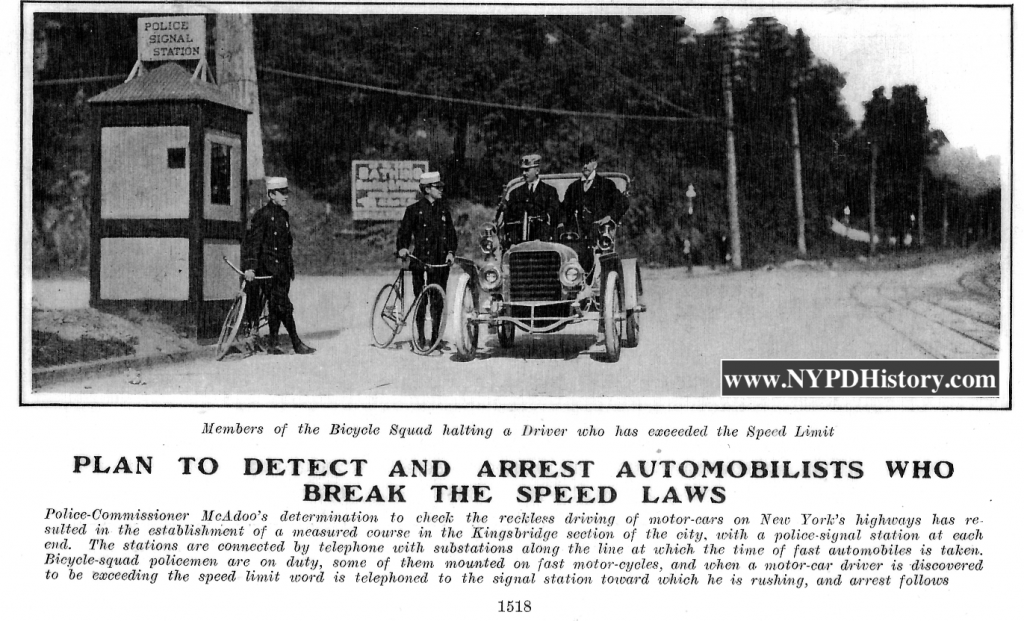

On October 15, 1905, the New York Herald carried a full page feature article entitled “The Need for An Automobile Police.” PC McAdoo, in addressing the drivers, or “scorchers” as they were commonly called, who sped about, detailed the use of a detection method invented by Allan Peabody which he described as being “absolutely accurate.” Stating that he wished the public to know where the detection system was used rather than appear to hide the same from them, he offered the locations to the public so that it would serve as a deterrent. Today, many jurisdictions using “red light cameras” post their locations on their websites.

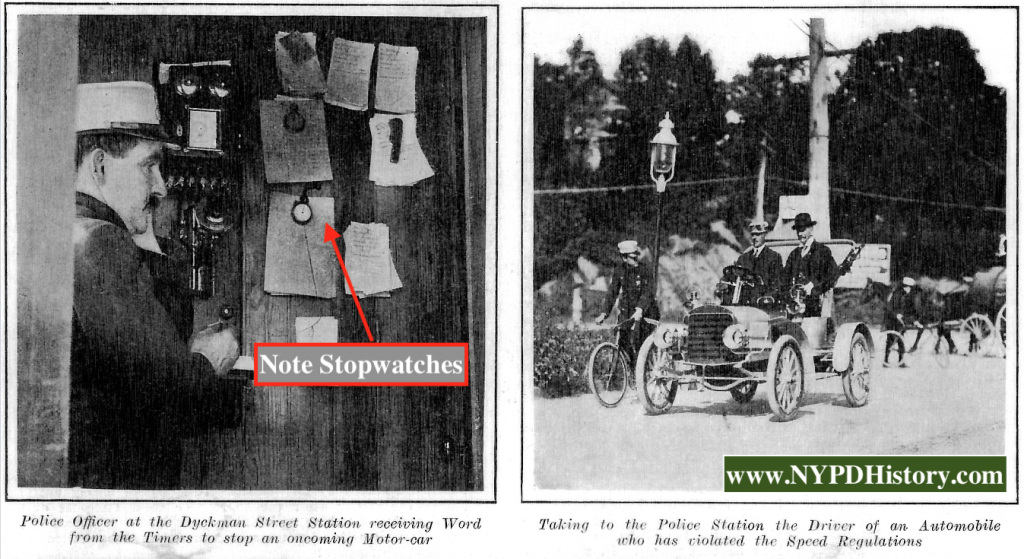

How exactly did officers after the turn of the twentieth century determine the rate of speed for an automobile when the vast majority of the officers had never been in one, let alone driven one? The answer, and Peabody’s method, lies on the fundamental laws of physics and the formula of “D= RxT” (Distance equals Rate times Time). The New York Times article of May 19, 1907, disclosed that officers carried a “printed table supplied by the Police Department. This is based on the speed in miles per hour computed from the number of seconds it takes a car to go a Manhattan block of 265 feet. The table varies from 6 miles an hour for a block covered in thirty seconds to thirty miles an hour in a block traversed in six seconds.” With some exceptions, the length of each block and width of avenues and streets in Manhattan’s “grid system” are equal.

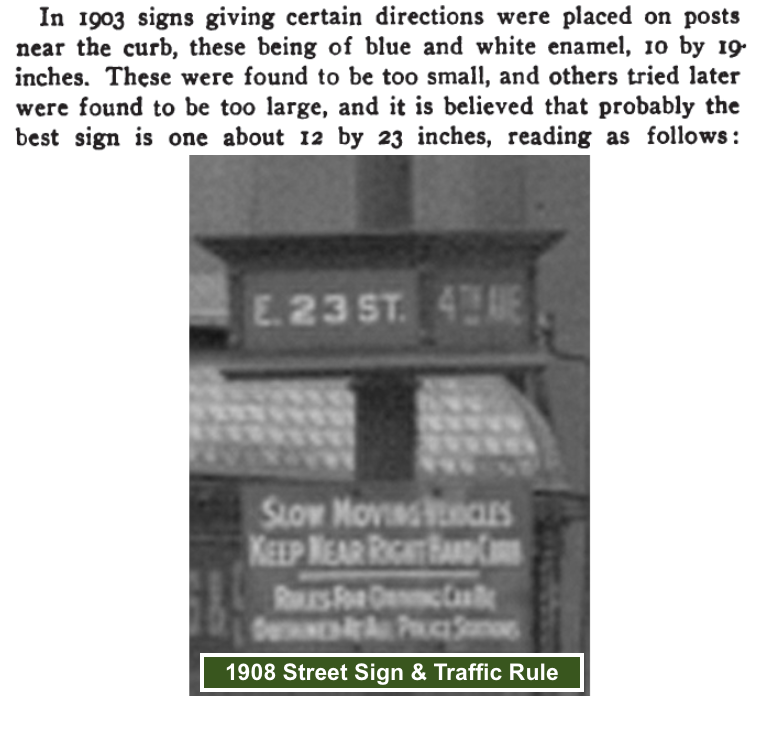

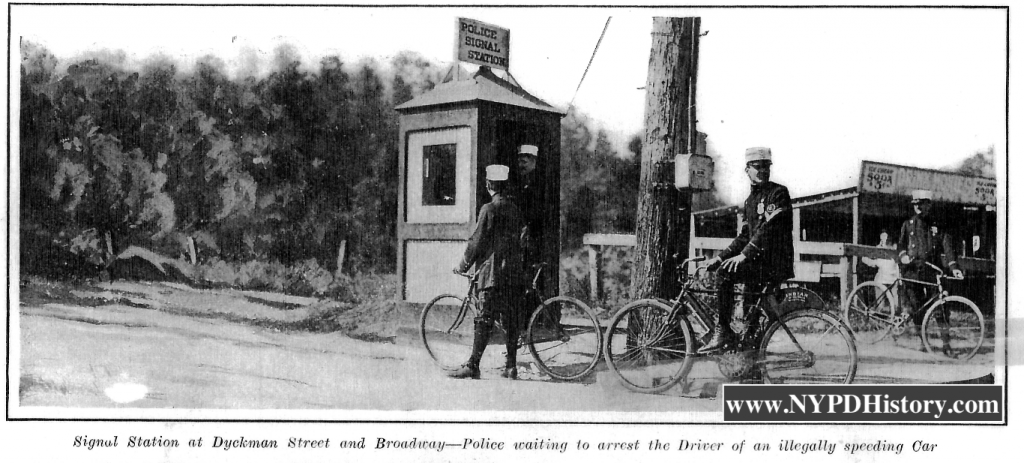

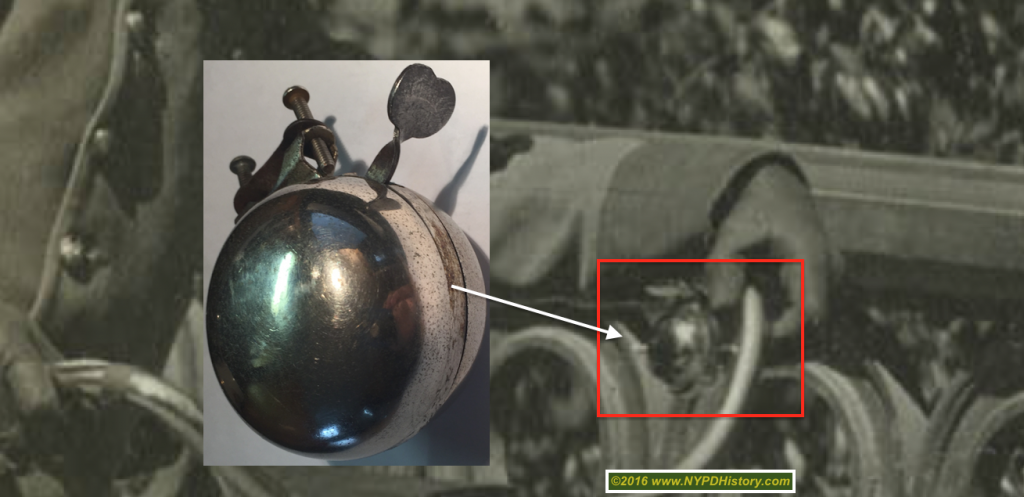

The same formula was used in the more rural areas of the city, even though the grid system of blocks and avenues had not yet become standardized. Again, the Peabody method and the formula (D = RxT) was in use, but rather than the length of blocks being used as a fixed distance, the distance between “Police Telephone Booths,” like the one depicted in the photograph, was used. These “Police Booths” were used as outposts for precincts in the rural areas of the city.

Manned by two or more officers, with at least one on a bicycle or motorcycle, calls were received from headquarters and officers responded to those calls from the booths. When used in speed enforcement, three booths were used. The first logged the license plate and/or description of the vehicle as well as the exact time that the auto passed the booth. This information was telephoned to the second booth down the road and the time was logged when the auto passed that booth. The rate of speed and description was telephoned to the third booth where awaiting officers stopped, or pursued the offending vehicle.

“What’s The Deal With: The First Enforcement of Automobile Traffic Laws by the NYPD?” The first enforcement of automobile traffic laws were undertaken by the Bicycle and Central Office Squads. With the exception of the first arrest for Reckless Driving in 1896 by Officer Wells, Officers John Scheussler, Benjamin Mallam and Eugene Casey can be credited as being three of the most active, and recognized, early enforcers of laws relating to the use of automobiles in New York City. Their connection to “the firsts” disclosed in this article (first: use of a bicycle, arrest for Reckless Driving, timed speed arrests) are significant, remarkable and deserve to be documented in the annals of the PDNY’s history!

If you’d like more information on the PDNY’s first department-owned vehicle, the Panhard-Levassor, check our website and Facebook Page for the article (Vol. 1, Issue 1A).

Mallam and Casey’s continued activity and ability to adapt to new tools and methods of enforcement as well as their place in the history of medals awarded to members of the department will be covered in the next issue of “The Deal.”

The bells used by the Motorcycle Squad and the Bicycle Squad were manufactured by the New Departure Co., Bristol, CT.

If you are interested in the history of policing in New York City, please visit our Blog at www.NYPDhistory.com,

“Like” our Facebook Page “NYPDHistory,”

and “Follow” us on Twitter at @NYPDHistory

Please share this article!

Mallam and Casey’s continued activity and ability to adapt to new tools and methods of enforcement as well as their place in the history of medals awarded to members of the department will be covered in the next issue of “The Deal.”

“The Deal” will be published when the Author has answers to questions about the history of policing in New York City.

Stay tuned for the next issue of The Deal where we will tackle the first use of an automobile in the enforcement of these laws. Guess who will be back? Yes. Casey and Mallam!

![]()

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.