“That men may rise on stepping-stones of their dead selves to higher things.” – Unknown Poet’s “Truth”

Introduction

Part 1 of this two part article examined the personal background and first 24 years of the police career (1874-1898) of Maximillian Frances Schmittberger. Part 1 ended In 1898, when Captain (Capt.) Schmittberger was at the low point of his career. Capt. Schmittberger testified before a New York State (NYS) legislative investigating committee, headed by NYS Senator Clarence Lexow, that he was engaged in criminal acts and named fellow officers involved in criminality. During his testimony, Capt. Schmittberger detailed the system of graft and corruption that permeated the Police Department of the City of New York (PDNY) and New York City (NYC) itself.

Despised by the majority of the department’s superior officers, the Democrat Party’s political machine (known as Tammany Hal), and the city’s politicians, Capt. Schmittberger was subjected to numerous transfers in precincts throughout the city and faced isolation.

It seems appropriate to repeat the last paragraph of Part 1 which best describes Schmittberger’s position within, and outside, the department after the Lexow Committee’s Investigation concluded.

“Schmittberger set to work to establish himself among the decent citizens. he kept his job, part of the reward for his treachery, and began a task few men would have the nerve to tackle. He had destroyed his own world; his former associates, and colleagues in crime, he had transformed into bitter relentless enemies. He had no standing with honorable men; it is a question which more heartily detested him, the crooks he deserted or the clean men he served. His life was not forfeit, perhaps, because his very ignominy threw protection about him, but he was threatened. Every old association he severed at a blow; the knitting of new ties was not easy, nor was it soon accomplished.”

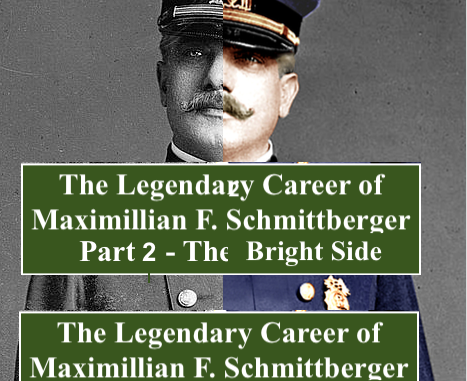

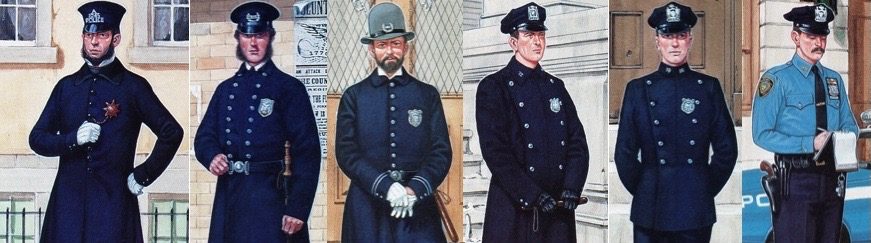

Part 2 will bear witness to the fact that, against all odds, Capt. Schmittberger restored his pre-graft reputation as a fierce fighter and rose to hold the highest-ranking uniformed rank within the PDNY. For the remainder of his 16 year career, Schmittberger became a highly respected leader who led the department into the next century with innovative ideas and concepts. Schmittberger helped to transform the Victorian era, pre-Consolidation department into the age of radio, motorized vehicles, war and challenges never before faced by his predecessors.

Like a Phoenix Rising From the Ashes – Schmittberger’s “Turn-around”

In January 1901, Capt. Schmittberger was assigned to the 13th Precinct and resided with his wife and children at 115 East 61st Street.

On February 22, 1901, by an act of the NYS Legislature, the Board of Police Commissioners was abolished and the title of Police Commissioner (PC) was created. The first solo PC was Michael C. Murphy. At the same time, in a political move which sought to remove the corrupt Chief of Police, William S. Devery, the title of Chief of Police was abolished by an act of NYS Legislature, thereby ending Devery’s career. In an act of defiance by the NYC Mayor, Mr. Devery was appointed First Deputy Commissioner (DC) of the PDNY.

DC Devery, continued his four year campaign of punishment against Capt. Schmittberger and, in April 1902, Capt. Schmittberger was transferred from the West 100th St. Station-house to the West 47th St. Station-house.

In 1902, Prince Henry of Prussia visited the United States. During his visit to NYC, Capt. Schmittberger, who was fluent in German, was placed in charge of the prince’s security detail. So impressed was the prince with Schmittberger, that he ordered that Schmittberger be inducted into, and receive the medal of, the “Prussian Order of the Black Eagle.”

In August 1902, Schmittberger, travelled to Europe on vacation. Upon his return he was met with news that his enemies, in an attempt to have him removed from command of the West 47th Street Station-house, levied allegations of corruption against him. When asked about his impressions of the police of London and Berlin, Schmittberger remarked that while the Berlin police looked fine in their handsome uniforms, spiked helmet, and swords, they were “asleep” and that the “Bobbies” of London were below par with their PDNY counterparts. To another reporter, Schmittberger remarked “If we had goings on here like I saw that night in London every Police Captain in the city would be hung.”

Redemption

“He is not only equal the equal of any man on the force, but I cannot think of any man who is his equal.” – A former Chief on Schmittberger

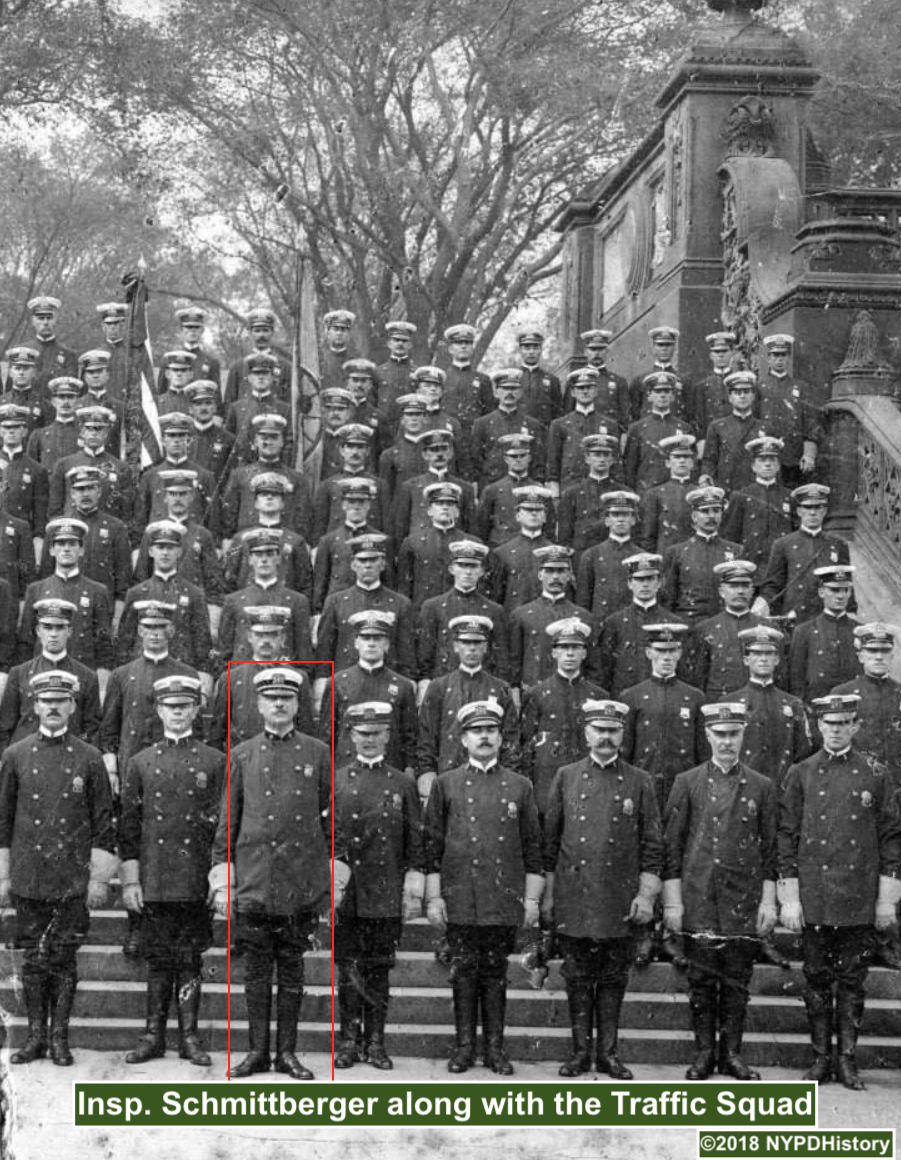

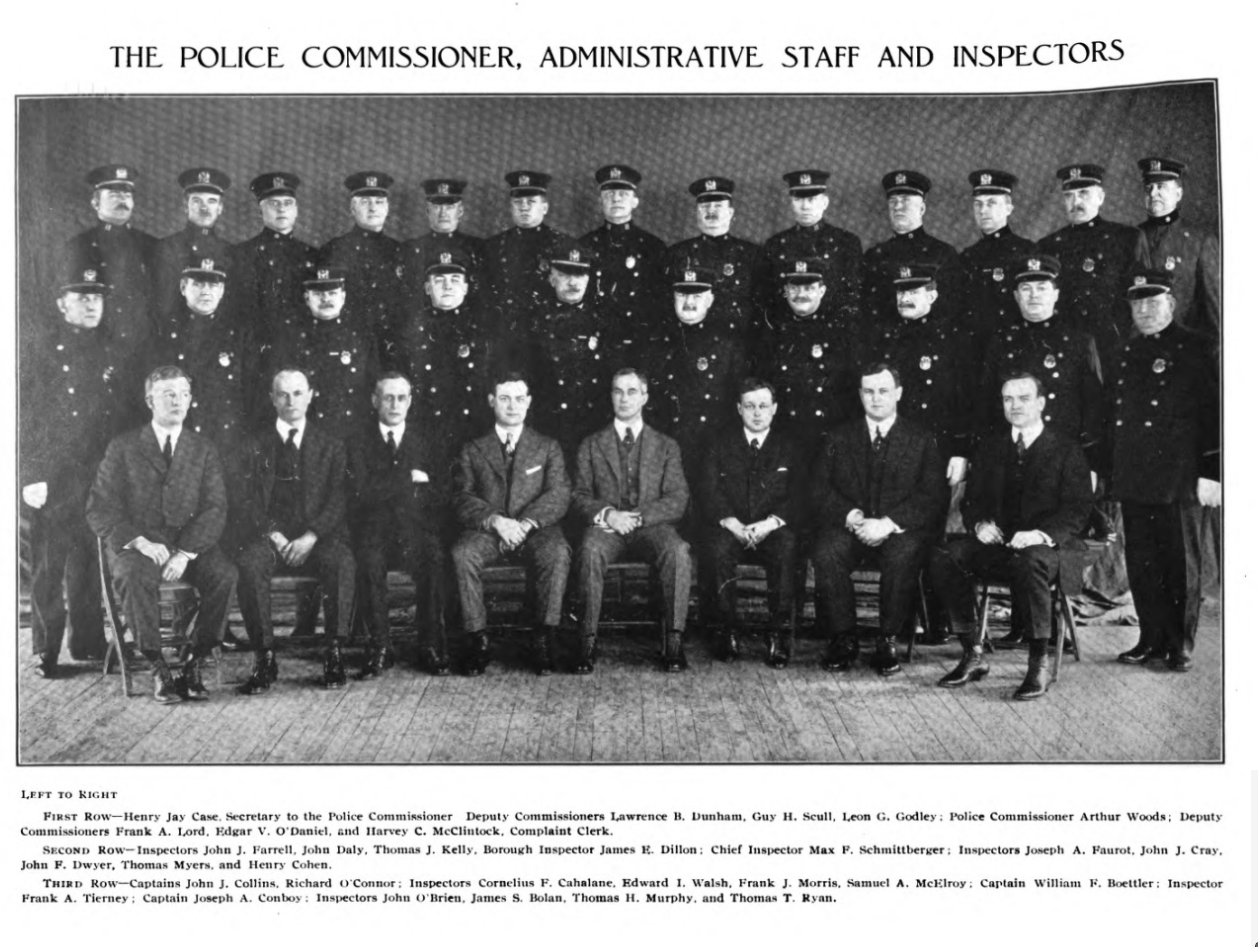

Under a “Reform” administration mayor, PC Francis V. Greene (1903-1904), on May 2, 1903, elevated, Capt. Schmittberger to the rank of Inspector (Insp.) and assigned him to the First Inspection District. The following day, Insp. Schmittberger would join the other inspectors and captains in the annual police parade.

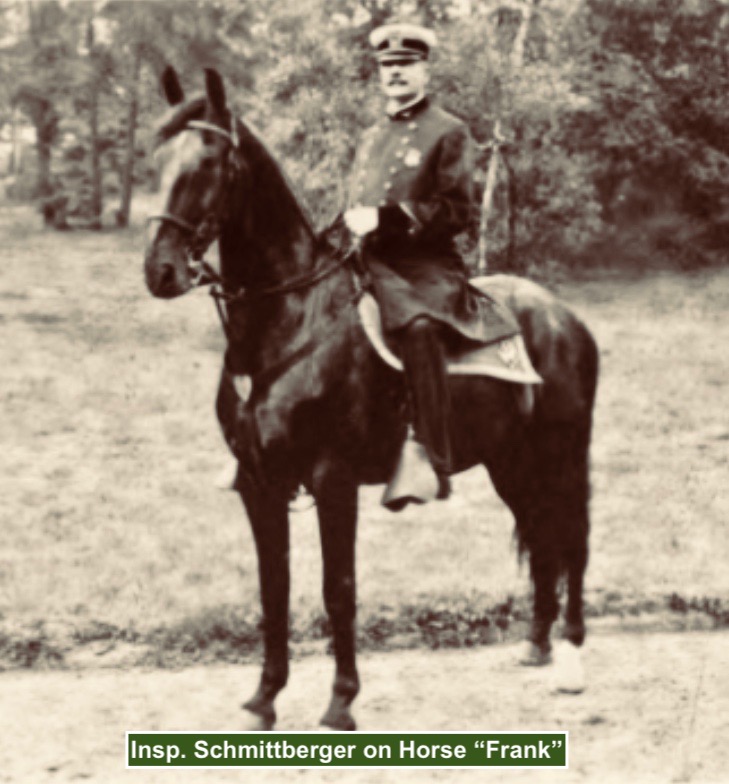

The parade began at Bowling Green (the southernmost point in Manhattan) and made its way up the narrowest part of Broadway. Insp. Schmittberger’s presence was at once noted by the spectators that lined the route. Schmittberger rode his well-groomed horse through the shower of confetti as the parade made its way through lower Manhattan. Throngs of spectators called out his first name “Max!” as they pressed forward into the police lines at the curbsides.

As he rode past the reviewing stand on Fifth Avenue at 40th St., Schmittberger’s head turned for the first time. Standing before him were the “distinguished guests,” many of whom had, “for nearly a decade…humiliated and ostracized him. They have ‘cuffed and cursed’ him, accused and slandered him with ‘nasty and vindictive’ attacks. Until this year – his year of redemption- they have forbidden him from even marching” in the police parades.

Not everyone shared in the crowd’s excitement and apparent support for the department’s newest inspector. The Tammany Times, a publication of Tammany Hall, took great exception to the promotion and wrote “Think of it! A man who is a self-confessed criminal, a blackmailer, ‘a squealer’…who has neither regard for the solemn oath…nor even a common sense of decency is promoted to one of the highest and most responsible positions in the department.” Of course, the paper did not address the fact that almost every officer exposed during the Lexow Committee’s investigation were either members of the Society of Tammany, or did the bidding of Tammany, including William Stephen Devery, the Chief of Police.

PC Greene received and overwhelming number of letters objecting to Insp. Schmittberger’s promotion. One letter, however, carried more weight than the others; that which bore the signature of the former President of the Board of Police Commissioners, and the then President of the United States (the President), Theodore Roosevelt.

The correspondence between President Roosevelt, PC Greene, and others is quite interesting. The following are examples of letters in support of and against Schmittberger’s promotion.

On January 20, 1903, PC Greene wrote President Roosevelt and asked the President what he “really” thought of Schmittberger. PC Greene wrote “Do you think promotion to Inspector would be wise or unwise having in mind its effect on the public, and would it have a good or bad effect on the force?” He continued “Dr. Parkhurst and Mr. Moss have volunteered the opinion that…his conduct since 1894 has been straight. As to this I have quite contrary reports, extending to Dec (sic) 1902, but whether they are true or not I am not yet quite sure. Both of them recommend him to me in the strongest possible terms. As to his ability, energy and force there is no question. As to his integrity – which is the vital point – ??”

The following day, the President wrote a response to PC Greene. In essence, the President wrote that during his tenure as President of the Board of Police Commissioners (1895-1897), Schmittberger performed “admirably;” that Schmittberger was “one of the most efficient members of the force;” and that he, however, had a “violent prejudice against (Schmittberger) because of his (Schmittberger’s) statements when he was State’s evidence.” In the end, the President left the promotion to the judgement of PC Greene.

Joseph Bucklin Bishop, Editor of NYC’s The Commercial Adviser, wrote the President on February 17 and wrote that “the methods used against him (Schmittberger) have been about the meanest I have ever seen employed against anybody.” In another letter, on February 19, Bishop wrote that he had spent hours with PC Greene on the Schmittberger promotion matter; that he believed that, due to political influences, PC Greene was “not playing it straight;” and that PC Greene was “trying to make a case against Schmittberger.” Interestingly, Bishop continued that PC Greene had “not a particle of evidence worthy a moment’s consideration to sustain” allegations against Schmittberger; that the Evening Post had “withdrawn all charges” published in an earlier article; and that he had lost all confidence in PC Greene.

On the other hand, letters were written to the President and PC Greene in opposition to Schmittberger’s promotion. One such letter, dated February 11, 1903, was written by Eugene A. Philbin. In essence, Mr. Philbin wrote that he does not believe that the Lexow investigation should have any connection whatsoever to the decision to promote Capt. Schmittberger to Inspector but that Schmittberger’s “record since then, and particularly recently, is such as would make it very detrimental to the best interests of the Department.”

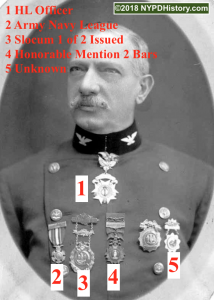

On May 24, 1905, Insp. Schmittberger, who spoke German fluently, was one of 200 officers who were awarded recognition for services at the scene of the General Slocum Disaster, which occurred on June 14, 1904. Insp. Schmittberger received a Commendation for his actions.

Moving Forward

The Slocum, named for a Civil War general, was a rear-wheeled paddle boat which, through the negligence of her Captain, caught fire and was run aground in the East River near North Brother Island. Over 500 passengers, largely German women and children who were on an outing, succumbed to drowning, smoke inhalation, and burns. Regarding the disaster, Mayor George B. McClellan stated: “The appalling disaster yesterday, by which more than five hundred men, women and children lost their lives by fire and drawing, has shocked and horrified out city.”

One year later, in July 1904, Insp. Schmittberger was among three police officials who were recognized for “their services in superintending the officers of their districts in preserving order after the Slocum disaster.” The officers were presented by a group of “prominent citizens” with “artistically engrossed diplomas, as well as heavy diamond studded gold medals.” The obverse of the medal was described as bearing the “Coat of arms of the City of New York, surrounded by a laurel wreath and several emblems of navigation” with an inscription on the reverse side.

Insp. Schmittberger’s reputation had turned for the better in the decade since testifying about his corrupt deeds and those of others. One of his allies was none other than the Reverend Doctor Charles H. Parkhurst. It was as a result of Parkhurst’s efforts that the underbelly of the city’s criminal element, and police corruption, was exposed and resulted in the creation of the Lexow investigation. In September 1905, Rev. Parkhurst praised Insp. Schmittberger, stating “I know of no man who can be relied upon to do such work as Max Schmittberger. I know the man. I knew him when he was bad, and I know when he turned around. I’m glad to see that Mr. McAdoo (PC William McAdoo) places such confidence in him. That confidence is not misplaced.” This was quite an endorsement as Rev. Parkhurst had the attention of the public, press, and city officials.

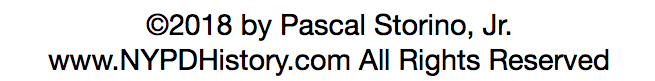

The Tenderloin Precinct continued to have a reputation as being “wide open” (permissive of illegal activities). In September 1905, the veteran of the Tenderloin who had once benefited from the system of graft and corruption in the precinct, returned to “lay down the law.” Insp. Schmittberger and the precinct’s commanding officer, Captain Dooley, assembled all of the keepers of disorderly places in front of the desk at the precinct. The “new czars” of the Tenderloin laid out the evidence that they had gathered on each of the individuals and advised them that they had twenty-four hours to change their ways or to leave the precinct entirely. To enforce the edict, and to conduct further investigations, two sergeants and six roundsman were added to the precinct.

In January, 1906, Insp. Schmittberger was assigned to the Central Office (Headquarters) Squad, resided at 115 East 61st St., and earned $3,500 per annum. However, in July 1905 a real estate transaction was recorded in which Sarah Schmittberger was a mortgagee of a five story building located at 254 East 30th St. The amount of the mortgage was $18,000. It should be noted that, according to her obituary, Sarah suffered from “cerebral meningitis” since May 1905, and succumbed to the disease on July 31, 1905 at a cottage she and Max had rented for the summer. The cottage was located on Grandview Avenue, Far Rockaway, Long Island. The obituary noted that the couple had six sons and two daughters and that Sarah was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx. Citing his real estate holdings, large donations to his church, and lifestyle, some historians have opined that Schmittberger never fully separated himself from the graft and corruption, however, little evidence has been presented to support these opinions.

Insp. Schmittberger’s rise would not be a smooth one. With changes in mayoral administrations and police commissioners (four new commissioners from 1901 through 1904) came changes in the way Insp. Schmittberger was dealt with by the department. Disciplinary charges and being “flopped” (a term used to described the act(s) of extraordinary transfers to less desirable precincts, or precincts far from home, as a form of punishment) were, and are, used to encourage a veteran officer to retire. As remains the case today, the last man standing wins, and Insp. Schmittberger outlasted quite a few commissioners.

Skulduggery and Revenge

In 1901, Roundsman Charles Becker worked for Captain Max Schmittberger. Seven years earlier, Schmittberger exposed the criminality of Becker’s mentor, Insp. Alexander “Clubber” Williams and Becker certainly embraced Williams’ violent exhibitions of “justice.” Even after his retirement, Williams’ influence over Becker remained evident to Schmittberger and others. Simply put, Schmittberger did not trust Becker and Becker despised Schmittberger.

In 1902 and 1903, Becker was part of an activist group of reform-minded patrolmen who lobbied and pushed for the adoption of a “Three Platoon System.” The Three Platoon System would have significantly reduced the number of hours that patrolmen worked. In 1904, Becker received the Department Medal of Honor for saving a drowning man, James Butler, in the Hudson River at 10th Street on July 24, 1904,.

Coincidentally, immediately after the “rescue” newspaper reporters, who had been called to the scene by Becker, appeared and the unemployed Baker praised Becker for his heroism. One week later, Butler contacted the same reporters and complained that Becker had not lived up to his end of a deal; that Butler staged the incident in return for $25 from Becker who wanted the medal and the accompanying promotion to the rank of Sergeant. When confronted with the allegations, Becker shrugged them off, but he had what he wanted, the medal and promotion. Soon thereafter, through his connections with the influential Tammany Hall, Sergeant Becker was promoted to Lieutenant.

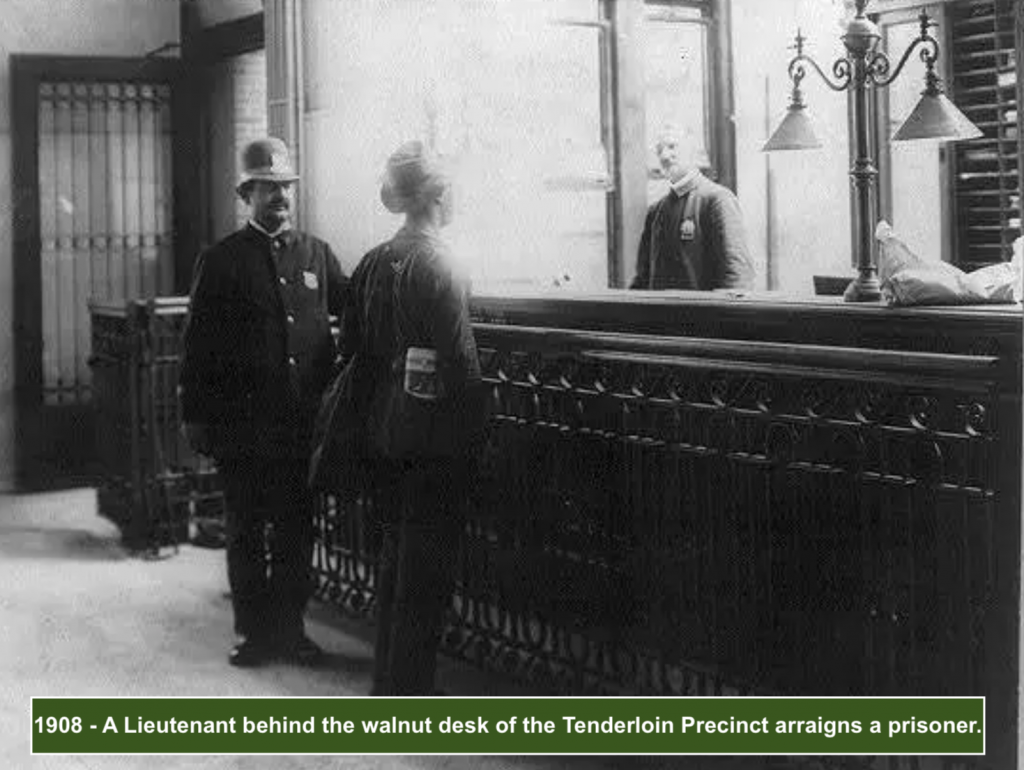

In 1906, acting on repeated allegations made by angry police officials of acts of corruption committed by Schmittberger, PC Bingham, assigned, then Lieutenant (Lt.) Charles Becker as the second in command of a special “secret” squad, working out of police headquarters, to investigate Inspector Schmittberger. It was alleged that Becker, acting as the “bagman” for Schmittberger exacted graft from illegal businesses with a vengeance, and that Becker received a 15% cut on everything he gave Schmittberger.

In January 1906, PC Theodore A. Bingham (January 1906 – July 1909) pursued disciplinary charges initially brought by his predecessor against Insp. Schmittberger for failing to supervise Capt. Dooley of the Tenderloin Precinct. This appears to be one of the first, if not the first, time that an inspector was held accountable for the actions of a subordinate. The allegations stemmed from a complaint filed by a patrolman who Capt. Dooley had assigned to work eight days in a row without time off. Capt. Dooley was fined eight days pay.

PC Bingham continued the practice of his predecessor (PC McAdoo) of using a squad of men who worked out of headquarters to perform raids of gambling houses, poolrooms, and brothels “above the heads” (performed without the knowledge of) the district’s inspectors. PC Bingham’s “Street Cleaning Squad” (also known as the “Red Van Squad”) succeeded PC McAdoo’s “Vice Squad” which had conducted successful raids over Insp. Schmittberger’s head and resulted in previous charges against Insp. Schmittberger.

The charges stemmed from a June 1906 raid conducted by PC Bingham’s squad of several poolrooms in the Tenderloin precinct which were under the command of Capt. Hodgins and within Insp. Schmittberger’s Inspection District. The charges levied were: conduct unbecoming an officer, conduct injurious to the public peace and welfare, and neglect and disobedience of orders and rules and regulations” of the department.

Insp. Schmittberger was represented by two attorneys. The defense put forth a “conspiracy” defense alleging that many of the men assigned to PC Bingham’s squad had been previously charged with offenses by Insp. Schmittberger and that the inspector had been singled-out for disciplinary action while the same conditions existed in other districts which were under the protection of politicians.

In January 1907, the charges were withdrawn, after the trial judge was presented with evidence that Insp. Schmittberger had in fact raided the premise in question; that the courts repeatedly dismissed the charges; and that witnesses had lied to PC Bingham. A newspaper ended its article with “The failure of this last case is in line with precedent, and Schmittberger may be expected to remain as inspector and to do good work in his position.

Lincoln Steffens publicly criticized PC Bingham for his persecution of Schmittberger and, in an open letter, threatened to testify that in a private conversation between him and PC Bingham, PC Bingham stated to Steffens that he was “out to get” Schmittberger.

At the trial, one of Schmittberger’s attorneys told the court that he was prepared to provide evidence, and cross-examine Becker should he take the stand, that Becker and the “drowning victim” had falsified documents and affidavits regarding the incident.

The story of Max Schmittberger and Becker continued for years hereafter and has literally filled chapters of books. Information relevant to the carer of Schmittberger has been presented in an abridged form. Becker’s tumultuous career and life ended on July 30, 1915 when, after being convicted for the murder of notorious gambler Herman Rosenthal, he was executed in the electric chair at Sing Sing Prison, “up the river” on the Hudson in Ossining, NY.

After his acquittal, on February 5, 1907, it was reported that Insp. Schmittberger was appointed to “one of the most coveted berths in the department as head of the Traffic Squad.” The “virtual promotion” was praised by his supporters (Rev. Parkhurst and Senator Lexow). One newspaper summed-up Insp. Schmittberger’s rise from the low point of his career (Lexow testimony) as follows “he has held his own in the department ever since, doing faithful and clever police work wherever he was placed. A recent banishment to Staten Island gave him an opportunity to tackle with credit a big murder case, and Bingham was pleased with his work.”

In fact, Insp. Schmittberger was in charge of the 14th Inspection District which encompassed the: Traffic Squad, 4th Precinct, Public Office Squad, License Squad, Brooklyn Bridge police detail, and the Trans-Atlantic Steamer Squad (or “Steamer Squad”).

In April 1907, PC Bingham once again “shook-up” the Inspectors and introduced a groundbreaking order that changed the command structure of the department, the effects of which remain to this date. On April 20, 1907, in accordance with Chapter 169 of the Laws of 1907, PC Bingham signed and promulgated General Order 20.

The order, effective April 19, abolished the rank of Roundsman and re-designated those to the rank as Sergeants. Likewise, Sergeants were re-designated to a new rank called “Lieutenant.” The order also gave the PC the right to designate any Captain to a detailed (non-Civil Service rank of Inspector; to demote Inspectors to the rank of Captains and assign them to precincts. In what had become an unofficial policy, tested by the charges against Insp. Schmittberger, the order codified the policy that inspectors were responsible for, and chargeable for, the efficiency and discipline of those under their command.

While the order demoted many long-time inspectors to Captains, promoted Lieutenants to Captains, and Captains to Inspectors, and re-assigned many men, Insp. Schmittberger retained his rank and command of the 14th Inspection District.

On the occasion of the annual police parade held on May 9, 1908, Inspector Schmittberger, rode his award-winning horse “Frank.” As the proud commanding officer of the Traffic Squad, Schmittberger led the First Brigade of the parade, which immediately followed the squad of Honor Men. “His men were mounted on horses, with their new saddles and bridles, and also a squad of bicycle men.”

In 1908, Brooklyn, which had until 1898 been an independent city with its own police department, was under the direct control of a First Deputy Commissioner (DC), William F. Baker. DC Baker had objected to Insp. Schmittberger’s control of the men of the Traffic Squad in “his” borough and complained in person to PC Bingham about Insp. Schmittberger’s “meddling.” The Traffic Squad consisted 500 men, 400 of whom were on foot and the remainder “mounted’ on horses and bicycles. Their duties included traffic control and enforcement of traffic laws.

Immediately after DC Baker left PC Bingham’s office, he promulgated an amendment to the new book of rules which took control of the Traffic Squad away from DC Baker and assigned Insp. Schmittberger as the Brooklyn & Queens Borough commander with orders to “rip things up” in the borough (Brooklyn). DC Baker then took vacation at the hot springs of Hot Springs, Arkansas. Adding insult to injury, PC Bingham sent Second DC Frederick H. Bugher, who had an antagonistic relationship with PC Baker, to replace Baker.

Union Square, Manhattan, was named for its proximity to the The Bowery, Broadway, and “Union Place” was named (as was Union Place) for being near the union of these major avenues. Ironically, as a result of the decades of activism for, and by labor unions and the location of the first Labor Day Parade, in 1997, Union Square was designated as a National Historic Landmark.

On March 27, 1908, an anarchist present at Union Square, attempted to kill Captain Miles O’Reilly with an improvised explosive device. Selig Silverstein (aka Cohen), a Russian anarchist, who resided in Brooklyn, attended an illegal (non-permitted) rally held in the square. As a result of recent demonstrations, the police commissioner denied the permit to assemble. Insp. Schmittberger was tasked with commanding a group of Mounted officers, stationed nearby, in the event that they were needed to disperse the crowd.

Those assembled refused to abide by orders to disperse and Insp. Schmittberger’s men, and others, were ordered to disperse the crowd. While attempting to throw the bomb, the bomb exploded in Silverstein’s hand, causing fatal injuries. Others were injured, maimed and killed. The officers responded with violence, but cleared the park while those who required medical attention were treated and the scene was investigated.

Click below to watch video

Insp. Schmittberger won praises from newspapers, civic leaders and the department for his previous dealings with protesters in the park, which were largely peaceful, as well as his liberal use of nightsticks on the day of the bombing. It was reported that Insp. Schmittberger gas “held out his nightstick” and said, “this (the club) at times, his over the Constitution.”

The department At a later event, an orator told a crowd “let us remove Madam Liberty from Beldow’s island and put there instead Inspector Schmittberger with his club.”

It would take time for the department to balance, and learn how to handle, mass public demonstrations without relying on the use of force, balancing the right to free speech with the need for public safety.

Schmittberger Leads the Department

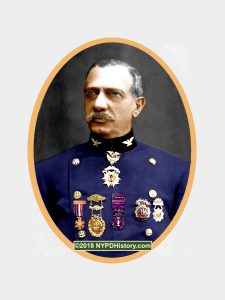

On February 18, 1909, Insp. Schmittberger, age 57, “sometimes called the best hated man” in the department was appointed Chief Inspector, succeeding Chief Insp. Moses W. Cortright, who retired nine days earlier after 42 years of service. Commenting on his promotion, Chief Schmittberger said “I think I can safely say that it has been a long, hard fight, honorably and honestly won. No man in the history of the Police Department ever had to make such a fight as I have made. Victory has come to me because I have ‘made good.’ I have reason to be a very happy man today.”

Like anyone who has lead any organization, Chief Insp. Schmittberger brought to the position the totality of his being to the job; personal, professional and life experiences. His Germanic heritage, reinforced by his observations of the police during a visit to Berlin, Germany in 1902, propelled his drive to prove himself worthy of the position and to put his detractors and enemies to rest.

Chief Schmittberger made visits after midnight of the posts in the various commands of the city to ensure that officers were actively patrolling their posts. During one such tour of the Bronx, on September 11, 1912, accompanied by a captain and patrolman, Chief Schmittberger entered a barn located on Ogden Ave., near 170th Street shortly before 5:00 am.

Upon entering the barn, they observed four horses munching on hay and, turning a lantern to the other side, four pairs of knee-high black boots sticking out from under a blanket. On orders of the chief, the patrolman pulled the blanket away which awoke the sleeping men who woke to see the highest ranking uniformed officer in the department standing over them. Upon returning to the Highbridge Precinct, the four sleeping mounted patrolmen were suspended along with two sergeants and the precinct’s captain who failed to supervise the men under their command. Let us not forget that it was the chief himself who more than a decade earlier was, most likely, the first commanding officer to receive the same charges.

Schmittberger studied the career of Field Marshal Helmuth Karl Bernhard Graf Von Moltke, the Chief of Staff of the Prussian Army from 1857-1887, and a renowned military strategist and tactician. Von Moltke restructured and enhanced every aspect of the military from training to preparedness, deployment and field operations. His theories and practices were studied by military strategists and are credited for many military victories.

Schmittberger was influenced strongly by Von Moltke, and implemented many of Von Moltke’s precepts in the department. PC Arthur Woods (1914-1918) remarked that Schmittberger “invoked the diktats of Field Marshal Von Moltke to many a subordinate.” Von Moltke’s successes in planning and strategizing were followed by Schmittberger in preparing for every aspect of police work from scheduling, command structure, training and deportment to readiness for terrorism and invasion by enemies. Terms used by Von Moltke relating to policies in the department such as “General Directives” (General Orders) and “Operations Orders” exist to this day.

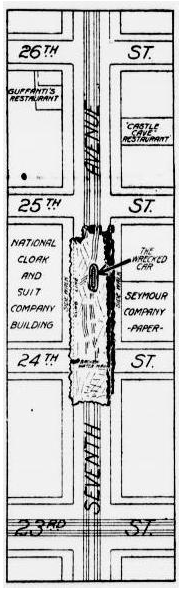

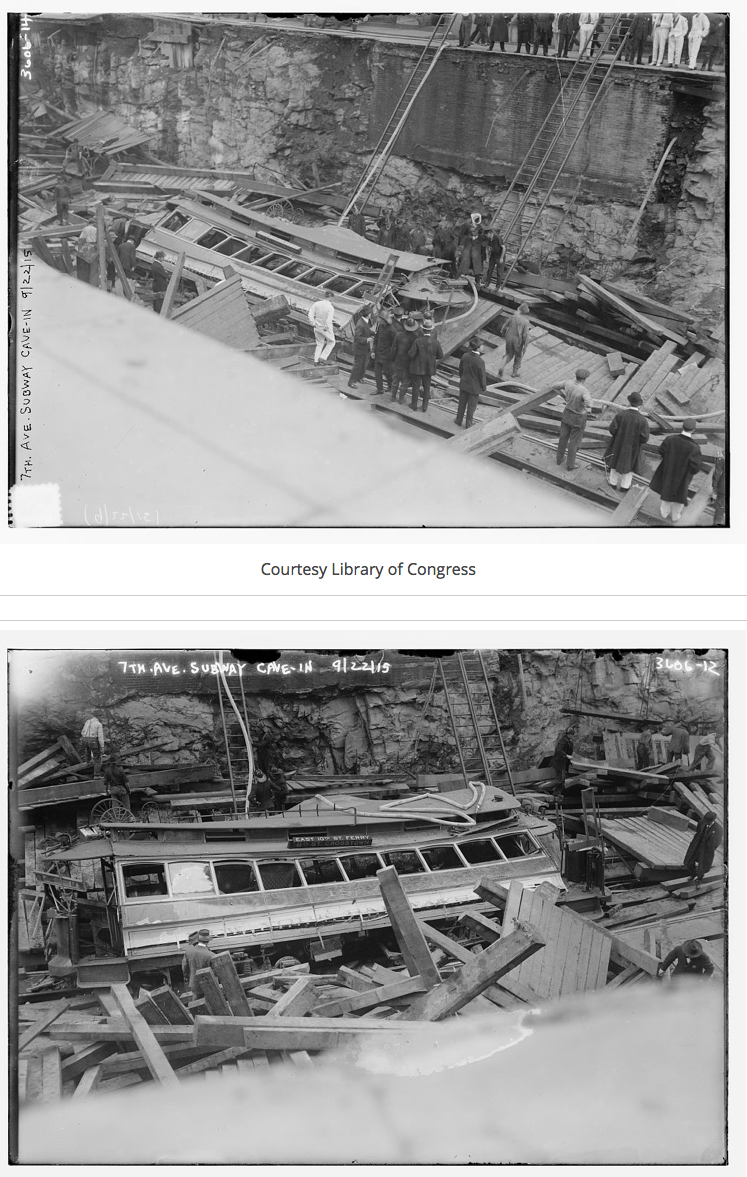

According to PC Woods, Schmittberger’s efficiency, planning and preparedness was best exemplified when, on September 22, 1915 “the bottom of two or three blocks of Seventh Avenue suddenly dropped out of sight, carrying with it pedestrians, wagons, horses, and street cars…to use the vernacular of the department (Woods) ‘pulled his Von Moltke stunt’; as, six months beefier, he had just such a situation. The orders were ready – ‘in the second drawer on the left.’ as Von Moltke said forty-five years before” when he was faced with a military crisis.

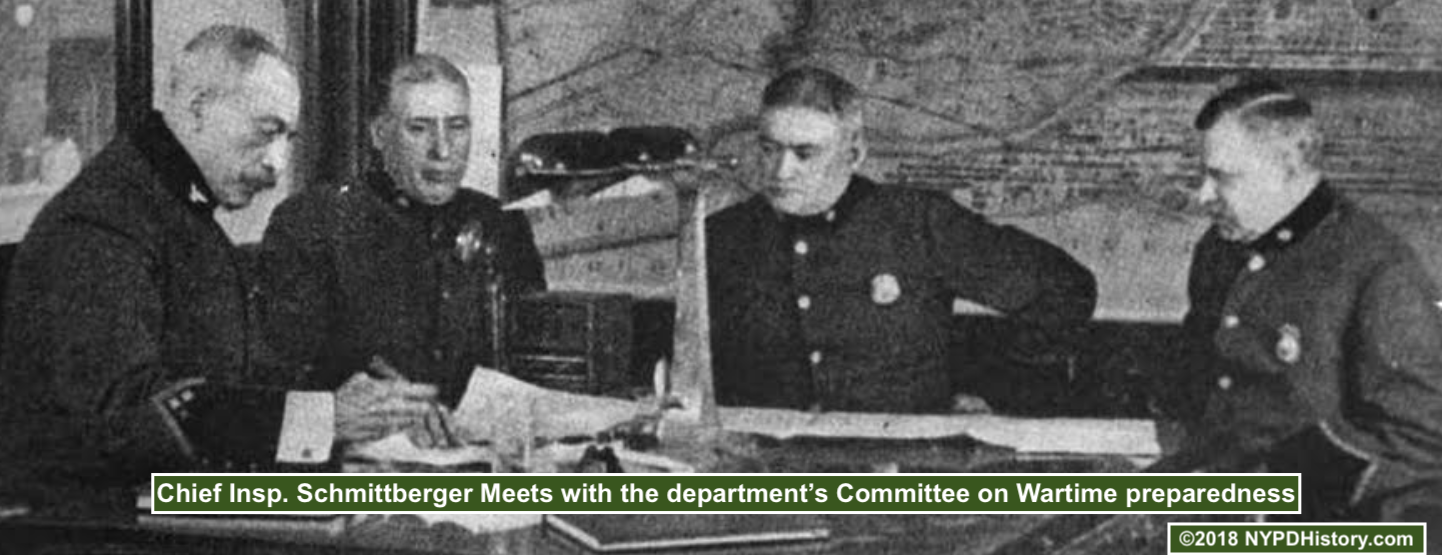

Wartime Preparedness

In 1914, with recent earthquakes and weather-related calamities fresh in their minds, the police department, under PC Arthur Woods, recognized that they needed to plan and prepare for such an event should the city be affected. Additionally, while the countries of Europe fought in what was called “The Great War,” and later World War I, Americans, particularly those on the east coast experienced attacks off their shores and in their harbors as well as on the land by enemies of the country and antagonists seeking to curtail America’s material support for Great Britain and France. America’s “neutrality” was challenged and its entry into the war seemed inevitable. The police department began to prepare not only for the eventuality of its entry, but to prevent and protect the homeland.

Chief Inspector Schmittberger formed the “Committee on Preparedness” which consisted of himself and several inspectors. Their goal was to formulate a plan to utilize city employees and citizens to act as an auxiliary to the regular force if and when needed. With the support of the federal government, a total of 45,000 persons were sought.

Inspectors and captains received lectures and “Schools of Instruction” were established in each Inspection District. Police officers received instruction from the military in setting-up “camps,” quartermaster, and commissary functions to serve large bodies of officers and displaced citizens. The “Plattsburgh Camps,” was one of these innovations.

Citizen training academies were formed, first in Brownsville, Brooklyn, where citizens were trained in ordinary police duties and traffic control. Regular officers canvassed their precincts gathering information on resources available in case of emergency such as large halls, hospitals, druggists, telecommunications, and kitchens. A registry of aeroplane pilots was created as well as motor boats capable of assisting the department.

Under PC Woods

“Schmittberger had perfected an intricate but perfectly operating system for the protection of the city in any great emergency. For instance, if the water supply is cut, the police will know instantly what to do, If the great East River bridges are wrecked, the police have arranged a system of communication by wireless, tunnels, and vessel. If bread riots occur, the police at headquarters have another remedy, devised by Inspector Schmittberger. He established wireless stations in various parts of the city in case the telephone fails.”

A “Division of Bridge Defense” was formed to protect the bridges within the city. Squads of officers were trained and equipped with .44 caliber Winchester carbines and stationery machine-guns and placed at points identified by engineers where the bridges were must vulnerable.

Other actions taken towards preparedness included the equipping of the Harbor Unit’s steamer “Patrol” with two rapid-fire one pound guns, and two .30 caliber machine-guns; station-house gymnasiums and athletic training.

On October 31, 1917, Max Schmittberger succumbed to the effects of pneumonia at his home located at 237 East 61st Street, Manhattan. Schmittberger was survived by eight children. His last words to his family, who were present at his bedside were that “the department be notified.”

On November 3, 1917, approximately 3,000 people assembled near the Schmittberger residence to pay their last respects to Schmittberger as his casket was taken from the residence to Saint Patrick’s Cathedral where a funeral mass was celebrated. The procession was led by the Police Department Band, dignitaries, Mounted officers, and a continent from the Honor Legion. Following the casket were approximately 200 carriages containing family and friends.

Schmittberger is interred in Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx beside his wife, Sarah and at least one son.

Other innovations that came to be under Schmittberger’s supervision were: 1) the utilization of the Wig-Wag System of communication to manage traffic and ultimately the use of Traffic Lights, 2) the formation of the Honor Legion, a fraternal organization whose members were recipients of departmental medals or commendation 3) theTraffic Squad, to deal with traffic flow as well as the enforcement of traffic laws 4) the Traffic Squad Benevolent Association, a fraternal organization whose members are assigned to the traffic Squad 5) the utilization of the Marconi Radio system to communicate between critical points, during disasters, and in the daily operation of the department and other innovations. Most of these have been covered in separate posts here at www.NYPDHistory.com.

Conclusion

What’s the Deal With Maximillian F. Schmittberger? Maximillian F. Schmittberger served under six Police Commissioners and remains only one of two Chiefs to die as active leaders of the department. Schmittberger is remembered as a good, fearless police officer; as a supervisor, a strict disciplinarian and organizer of innovative policies and procedures; and a man whose deportment and professionalism was carried by the men of the department. He must also be remembered as someone who chose to violate the law and participated in the systemic graft and corruption that permeated the department for decades. By testifying before the Lexow Committee, Schmittberger was, for decades, remembered as an officer who destroyed the careers of many of his superior officers, peers and subordinates.

Against all odds, Schmittberger “convinced a cynical town that repentance may be based on something more enduring than the dear of exposure, and reform may be carried through the dace of apparently insurmountable obstacles and in the unwavering light of publicity.”

Historians will continue to debate his efficacy and role in the history of policing in New York City.

The Author would like to thank Mr. Ed Sere for his contributions to this article, including some of the images used to enhance the same. Ed is a true custodian of history, not only of the NYPD, but the FDNY and the U.S. Marine Corps! Hoorah!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.