Background

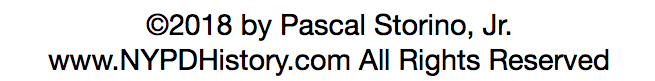

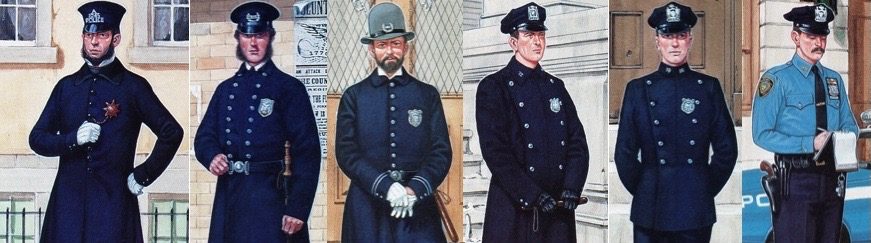

Debates on immigration and concerns about admitting criminals into this country have existed for centuries. During each period of immigration, the police dealt with not only an increase in population but also the criminals and crimes they committed. Sometimes the department handled the challenge with traditional responses such as an increase in the total number of the force and/or the reallocation of manpower to various districts where the immigrants settled. From the late 1880s through approximately 1915, approximately 1.75 million Italian immigrants passed through Castle Garden and later, Ellis Island. Many immigrants remained in New York City (NYC) and settled in the communities where other immigrants from their country had previously settled. The Italians brought their language, customs, traditions, and food (thank God) along with them. As was the case with any immigrant population, a small percentage of them were criminals. The department was unable to significantly meet the challenge of policing these Italian-on-Italian crimes with its largely Irish and German-born officers and traditional enforcement and investigative practices. For the first time, the NYPD created a specialized unit to address these Italian criminals and their crimes.Regarding the criminal element of Italian immigrants, Deputy Police Commissioner (DPC) Arthur Woods wrote “these people are respectable, industrious and self-supporting. Mixed with them, however, there has flowed into this country a thin stream of immigrants…who have left criminal records behind them in Italy; these are the Black Handers. In New York it has been found that in almost every case that a man arrested for a Black Hand crime has been convicted of a crime in Italy.” DPC Woods added that the criminals settle amongst their countrymen and “proceed to prey upon them” like “parasites, fattening off the main body” of their kind. The “Black Hand” was a term used to describe both the Italian(s) committing the crimes and the type of crimes themselves. Essentially (for purposes of this biography), the term stemmed from the inclusion of an outline of a hand, sometimes accompanied by a bleeding heart or other sign at the end of a threatening letter used to extort or strike fear in a victim(s). Italian-immigrant criminals preyed on their wealthy countrymen by kidnapping their children, threatening to blow up stores of homes to demand ransom money, etc. The letters were signed “La Mana Nera” (the Black Hand) and struck fear in the community.

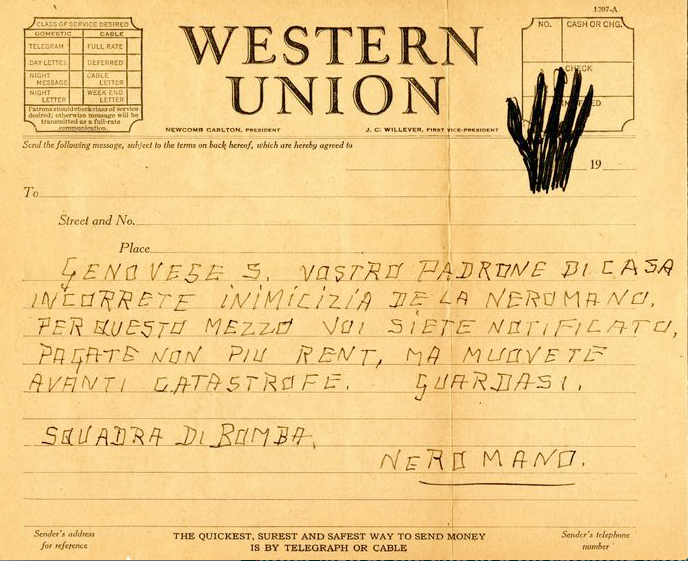

In 1904, the Police Department of the City of New York (NYPD) created an “Italian Secret Service”(“Italian Squad”) which after one year of was deemed by Mayor John P. Mitchell (1914-1917) to have “proven eminently satisfactory” in their work. The unit, comprised, with the exception of one Italian-speaking detective of Irish origin), of all Italian-American officers, was created for the purpose of “keeping pace with that lawless element which is prevalent to some extent among our rapidly increasing Italian population,” wrote Mayor Mitchell. The department likely chose the name “Secret Service” after having worked with the U.S. Secret Service on many cases involving Italian immigrant counterfeit rings.Police Commissioner (PC) Theodore Bingham (1906-1909) asserted that the police force of 10,000, with only approximately fifty Italian speaking men and fewer who spoke the southern Italian dialects, was unable to police the newly 750,000 Italians in the city.There was no question as to who would lead the unit. Lieutenant (Lt.) Giuseppe Petrosino had for years lobbied the police commissioner to form such a squad. It would be Lt. Petrosino’s duty to recruit officers to work in the squad, which initially worked out of a nondescript building. For their own safety, and that of their families, the identities of the officers assigned was known only to the police commissioner and a very small number of the highest ranking members within the department.

The following is a brief look into the career of one of the early detectives assigned to the Italian Secret Service Squad of the NYPD.

The Rise of the Career of Michael Mealli

Michael Mealli (Also spelled “Meali ” in some sources) was born in Italy in 1876 and emigrated to the USA.

In August 1902, Michael Mealli, of 10 Navy Street, Brooklyn, was appointed as a fireman to the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY) and assigned to Engine Company 108. In December 1903, Mealli was appointed as a Patrolman (Ptl.) of the NYPD and was assigned Shield 3529.

In May 1903, charges for “Conduct Unbecoming an Officer” were dismissed against Ptl. Mealli, of the 50th Precinct (Fulton Street, Brooklyn Station-house). Three months later, in August 1903, Mealli was fined one-half days pay for “Neglect of Duty.”

In 1904, in a group photograph of the early “Italian Squad,” a portrait photograph of Mealli, wearing a Detective (Det.) shield (#215) appears among the other early members of the squad.

In March 1904, Mealli was transferred from the Central Office to the Headquarters Squad, Brooklyn, for duty in the Detective Bureau. For reason(s) not known at this time, in August 1904, Mealli, was “Remanded to Patrol.”

Det. Mealli’s increasingly troubled career continued to garner the attention of the department when on May 27, 1907, at 4:00 am, he and Det. Paul Simonetti, members of the Italian Squad, were arrested on the complaint of a streetcar conductor and charged with disorderly conduct for annoying passengers and refusing to stop when asked to do so by the conductor. The case was put over and no disposition was disclosed.

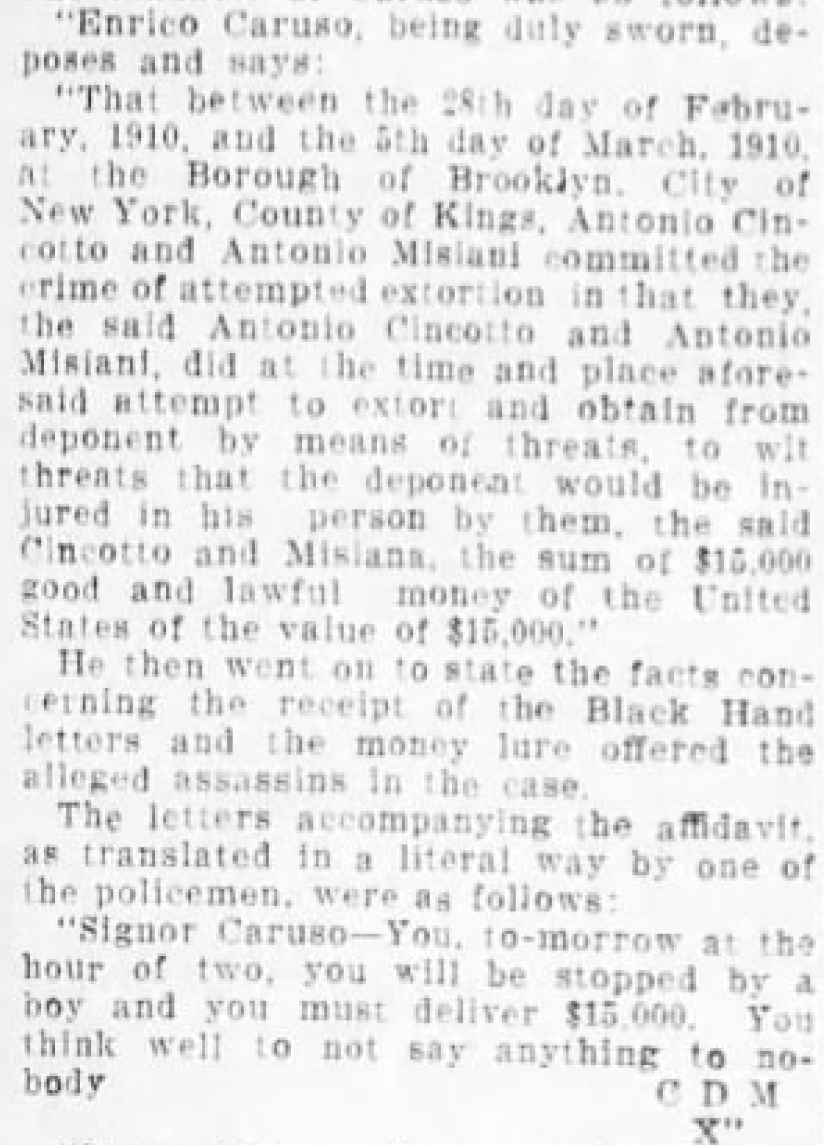

In March 1910, in what remains one of the most high-profile cases investigated by the Italian Squad, Det. Mealli and others arrested Antonio Cincotto and Antonio Misiani on the complaint of world-famous tenor Enrico Caruso. Mr. Caruso appeared in court in Brooklyn and swore to a complaint which alleged that the two men extorted $15,000 from him by the means of threatening letters. Both men were convicted at trial and sentenced to a term of imprisonment “up the river” at Sing Sing Prison, Ossining, NY, on the Hudson River.

Cincotto’s life ended on February 15, 1915 when, after his release on bail from Sing Sing while his case was heard by the Court of Appeals, he was shot twice in the head. Cincotto had been successful in defending himself against charges for two murders and a host of other offenses prior to his conviction for extorting Enrico Caruso.

Shortly after midnight on October 10, 1910, at 295 Third Avenue, near Carroll St., Brooklyn, Antonio Lauro, the proprietor of a coffee house at that location, was charged in connection with he shooting of two men; Blazio Coppola and Aniello Grimaldi. Grimaldi was awaiting a second trial for murder, was free on bail at the time he was shot.

With his disciplinary transgressions apparently behind him, between 1912-1914, Det. Mealli, partnered at times with his brother Det. Andrew Mealli, investigated a number of Black Hand crimes and was referred to by the press as an “Italian specialist.”

The Downfall of the Career of Michael Mealli

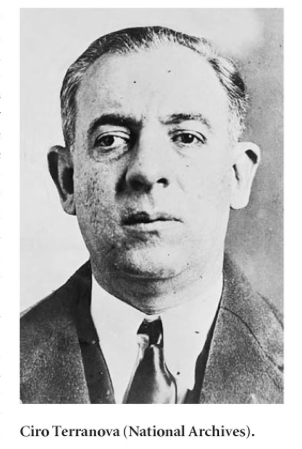

“The terror of evildoers, waded into a gang of ‘bad’ men near the Navy Yard” alone on August 7, 1914 and pointing to two of the Navy Street Gang’s members said “Come socially or in an ambulance.” The gang’s leader replied “We’ll go anywhere with you Mike; we don’t want to start anything with you.” Two of the gang’s members went along with Det. Mealli and were charged with robbery. It is not clear if the gang leader’s sheepish reply was made out of fear, respect, familiarity, or a combination thereof. What is clear from news accounts is that the reply indicated a familiarity that proved to extend beyond that of a detective who had only frequent job-related encounters with the gang.

In an effort to obtain the penal records of Italian emigrants to the USA for the purpose of deporting them from this country, Lt. Petrosino was sent to Palermo, Sicily, Italy on a “secret” mission. The secret did not last long and word spread to Palermo of Lt. Petrosino’s presence and goal. On March 12, 1909, Lt. Petrosino was murdered and became the first, and only, NYPD officer killed in the line of duty outside of the USA. After Lt. Petrosino’s assassination, the Italian Squad was disbanded, but the work of the squad continued on in a less centralized manner with “branch detectives” taking on the work.

Many of the Italian Squad detectives lived in the “Italian colonies” of the city. This was, of course, beneficial as it provided the familiarity that was necessary to obtain information, and detrimental as it exposed the detective and his family to the possibility of threats, coercion or worse. In Det. Mealli’s case, he resided at 10 Navy Street and the Navy Street Gang’s eponymous name indicates that they were all familiar with one another.

A Line Crossed

In January 1915, the gruesome murder and dismemberment of sixty year old Rufus Dunham, a collector of installment payments for a furniture business, marked what one newspaper heralded as the first murder of its kind, committed by the “low and brutal of the Italians of the city’s population of an “American-born” person. The article continued “This class of mutilating murderer has confined his operations to those of his own nation and kin. In fact, it was not an uncommon boast of the police that they did not mind what happened as long as the murderers confined their operations to themselves.” In the view of the press, the public, and the police department, a line had been crossed.

Mr. Dunham’s bisected torso, absent limbs and a head, was discovered in a swamp at Bay 50th Street near the West End Railroad. One of the thirty detectives assigned to the Sixth Branch Detectives, located at the Poplar St. Station-house, assigned to the case was Det. Mealli. In this period, detectives maintained a list of all of the laundry businesses in the city. Each clothes launderer had a unique mark, referred to as a laundry mark, which identified the owner’s business. The term “laundry list of things to do” stems from the practice of a detective reviewing the extensive list in order to identify the launderer of a piece of clothing.

The medical examiner concluded that whoever dismembered Mr. Dunham’s body possessed the skills of a butcher. Red Hook, Brooklyn was abuzz. While Det. Mealli and others made arrests for weapons possession, in violation of the Sullivan Act of 1911 (requiring a license to possess firearms in New York State), and other crimes in an attempt to put pressure on Red Hook’s Italian community to provide information on the murder, it was learned that the murder took place in front of 23 Union Street at 10:30 pm, while Cincotta was in the company of Frank Ricciardi.

In July 1915, Det. Mealli was in Geneseo, in upstate New York, where he took into custody Cristofico Incarvario, aka Andrew Carl, who was wanted by the NYPD for the murder of a man in NYC three years earlier. Incarvario was also implicated in the murder of a “countryman in Cleveland.” When an officer from Cleveland attempted to arrest him, he fired one round at the officer gravely injuring him. In his hometown of Mt. Morris (Geneseo County) he was charged with attempted murder in connection with the shooting of Sam Capadonia. Unable to secure a conviction, Incarvario was released.

The War Years

During the period preceding the entry of the United States (USA) into the war in Europe, the USA supported the war effort in many ways, including the shipment of various items to European ports. The Germans sought to stem the tide of ships carrying supplies by hunting them on the high seas and, using submarines, sending them to the bottom of the ocean. The Germans also relied on a network of spies and anarchists to gather intelligence as to what companies and ships made it their business to support the anti-German countries.

Several acts, which today we describe as “acts of terrorism,” shook the city to its core, literally and figuratively. The largest blast was the Black Tom Island explosion which took place on July 30, 1916, in New York Harbor. In short, it is believed that pro-German bombers caused an explosion at the warehouses that stored ammunition and explosives that were to be shipped to Europe which were stored on Black Tom Island.

In December 1915, Det. Mealli, Sixth Branch Detectives, was assigned to assist Fire Marshal Thomas Brophy in the investigation of a suspicious fire aboard a British steamship berthed at Warren St. Brooklyn. The ship was used to deliver sugar to British and French Ports in support of the war effort against the Bosche (Germans). Her fire was the latest in a series of similar suspicious fires aboard supply ships.

Post-Petrosino Era Work by Det. Mealli

Books and movies have been published about the work of Petrosino’s Italian Squad and the cases investigated by the officers who continued to do Petrosino’s work after his murder and the dissolution of the Italian Squad. The most infamous of which was a gang war that caused fear beyond the Italian neighborhoods.

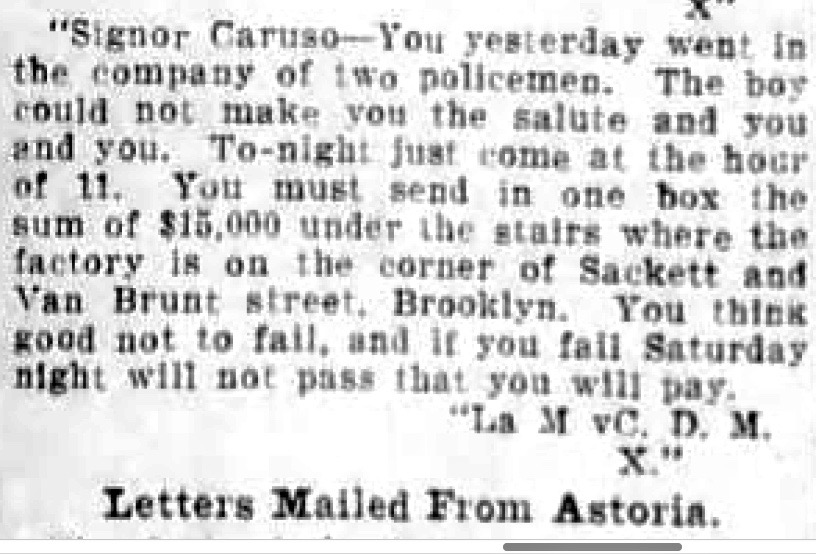

Det. Andrew Mealli, also assigned to the Sixth Branch Detectives, worked together on quite a few cases in this period including those of “The Artichoke King,” Ciro Terranova and his criminal gang and associates. Terranova, an importer of artichokes, resided in the Italian neighborhood of East Harlem where he used a horse stable to murder victims. Terrnaova’s gang’s feud with the Navy Street Gang resulted in many murders and shootings which led to many arrests by those officers who continued to do the work of Petrosino’s Italian Squad after Petrosino’s murder.

Det. Mealli’s familiarization with the Navy Street Gang gave him an advantage in the investigation of the dozens of criminal acts which included: murder, attempted murder, robbery, arson, bombings, and so on. Det. Mealli’s success was attributed to his ability to recognize faces and to identify criminals by name. As Det. Michael Mealli’s efforts resulted in an increasing number of arrests and convictions, his reputation with the department and the public appeared to strengthen. However, as had been the case with some well-respected officers who preceded and followed him, Det. Mealli’s career came to an abrupt end.

Exposed, Det. Mealli’s Career Ended

In February 1918, Ralph “The Barber” Daniello was a key witness for the prosecution in connection with the trial of nine Italians who were on trial for the murder of two Italians. Daniello testified that he had overheard two members of the Navy Street Gang wherein one stated that he was required to contribute fifty dollars towards the gang’s fund which existed to make payments to Det. Michael Mealli. While it is unclear as to exactly what the payment(s) were intended for is unclear, what is clear is that it/they were improper and illegal.

Det. Michael Mealli was reduced to the rank of Patrolman and assigned to patrol duty in a precinct. The “bust” of rank for such charges was a blow to the prosecution, the reputation of those officers who continued to do post-Petrosino era Italian Squad cases, and to the department as a whole.

In December 1918, with fifteen years of service, Det. Mealli, assigned at the time to the Headquarters Squad of the Brooklyn Borough Detectives, separated from the NYPD. No criminal charges were brought against him in connection with the allegations made by Daniello.

After his separation from the NYPD, Mealli went on to open a detective agency specializing in maritime cases. His brother Andrew continued his career with the department and he retried with the rank of Lieutenant, and passed away in 1938.

Michael Mealli died on July 24, 1939 at sixty-three years of age.

Conclusion

Faced with a growing number of violent, serious crimes committed by Italian immigrants against Italian immigrants, the NYPD recognized that the department lacked the ability to adequately address the situation. After years of investigating these cases, largely on his own, Lt. Giuseppe Petrosino finally persuaded the department that a specialized unit comprised of Italian detectives was required to investigate what was termed Black Hand crimes committed by Italian-immigrant criminals. Officers fluent in the various dialects of the Italian language and who possessed an understanding of the customs of the Italian immigrants were chosen for the squad.

Lt. Petrosino’s squad successfully investigated the crimes and made numerous arrests but were frustrated with the federal government’s deportation laws. In 1909, Lt. Petrosino was killed in Palermo while on a “secret” mission to obtain the penal records of Italian emigrants to the USA for the purpose of having them deported upon his return to New York City. After Lt. Petrosino’s death, the Italian Squad was disbanded but the same detectives continued their work from the branch offices to which they were assigned.

Det. Mealli was an early member of the Italian Squad and was an effective investigator who brought many significant cases to a successful prosecution and conclusion. Perhaps he was too familiar, however, with the members of the Navy Street Gang which dominated the neighborhood in which he lived. A gang member turned witness for the prosecution provided testimony that Det. Mealli received bribe money by the Navy Street Gang for his cooperation with the gang.

Det. Mealli was reduced to the rank of Patrolman and voluntarily left the NYPD in 1918 to pursue a career as a private detective who specialized in maritime cases. Mealli died in 1939.

As is the case with all of his articles, the author welcomes constructive criticism, corrections, additional information. The author can be contacted at the following email address:

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.