![]()

Click here to read Part 1 of this multi-part essay then return to this article.

The War in Europe; National Defense Preparedness Drove Change

As was the case with bicycles, motorcycles and automobiles, airplanes initially served as the “playthings” of the wealthy. Flying lessons and planes were, after all, expensive and only the well-heeled of society could enjoy them. Clubs formed which brought together like-minded individuals who enjoyed sharing their knowledge and experiences. These clubs became important advocates and lobbyists for advancing the rights of members, engaging in the legislative process and working with law enforcement to protect rights and minimize restraining laws that impacted their activities.

As more manufacturers entered the markets, and the manufacturing processes became more efficient, the prices of the aforementioned modes of transportation made their way to the masses. Airplanes, however, did not become as ubiquitous as the bicycle, motorcycle or automobile. As there was still no national air force, the responsibility of guarding the sky and repelling an attack fell on the PDNYC.

On January 31, 1918, a division of the PDNYC unlike any other in its history. In light of the threats posed by Germany to the eastern coast of the United States by way of air and sea, and in consideration of the possibility of the USA’s entry into the war in Europe, the Division of National Defense was created within the PDNYC. The Division became the point of contact between the Department and the Federal Government. In addition to being responsible for 589 miles of waterfront in NYC, the Division was charged with protecting the infrastructure including: marine, bridges, Selective Service Draft enforcement, alcohol enforcement, enemy aliens, blasting, military deserters, and the appointment of Special Patrolmen, amongst other duties.

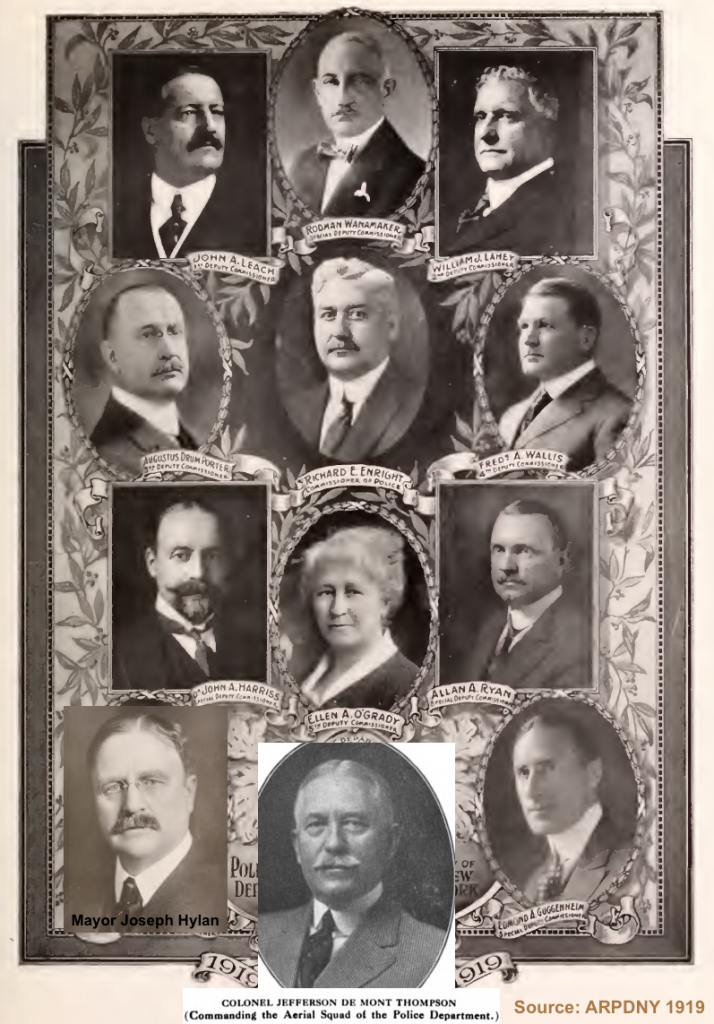

In 1918, Mayor Joseph F. Hylan (1918-1924), and Police Commissioner (PC) Richard E. Enright (1918-1925), turned to the millionaire class of men to lead the way in many innovative programs, policies and developments including, in this era, National (Home) Defense and police aviation services. The City turned to the members of the Aero Club for their financial support, expertise, and their active participation as members of the air reserves.

1917; The “Police Reserve Force” & the “Aviation Division of the Police Reserves”

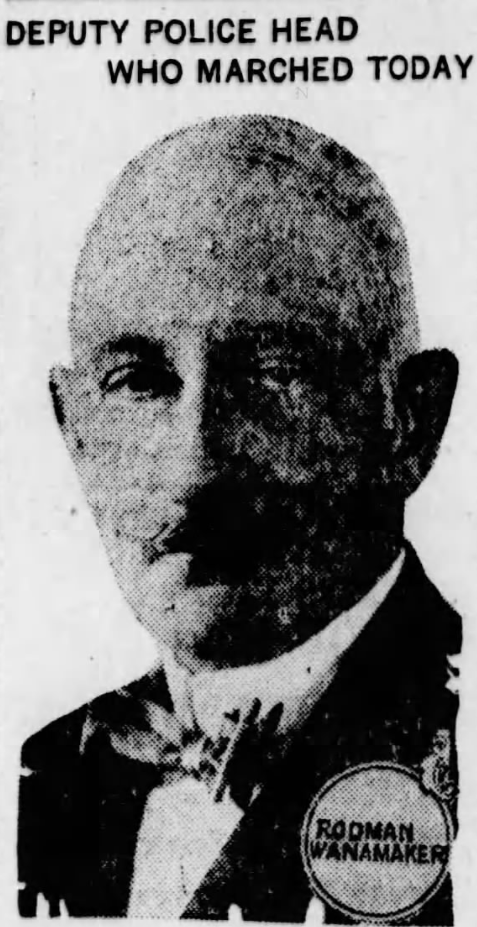

In the same year the USA entered the Great War (1917), Allan A. Ryan, a well-known aviator and Aero Club member, was appointed by PC Enright as Special Deputy Commissioner (SDC) for National Defense. Mr. Ryan joined two other millionaire Deputy Commissioners (DC); John A. Harriss, responsible for traffic; and SDC, (an aviation enthusiast known for promoting the concept of a trans-Atlantic flight) in charge of the “Police Reserve Force,” an “auxiliary to the Police Department.” SDC Wanamaker, nearly a decade earlier (1909), purchased a Bleauriot monoplane in France and transported it to the USA In 1914, he donated a large balloon to the U.S. Army which was used to train pilots before they went overseas.

In March 1918, PC Enright issued the following order to the Inspectors of the Department: “You will take immediate steps to secure for the aviation division of the police reserves young men, between 18 and 20, who desire to take up the study of aviation. It is desired to start immediate instruction in aviation ground work with a class of 100 young men, who will be trained and instructed free of charge by this department.”

SDC Wanamaker followed PC Enright’s announcement and proclaimed that the “Police Reserve Force” (the predecessor of today’s Auxiliary Police) was to be formed; that once formed, it would be combined with, and then replace, the existing Home Defense Corps, instituted by Mayor John Purroy Mitchell (1914-1917); and that it would have two separate divisions. The two divisions of the Police Reserve Force were the Police Training Corps (to train Police Reservists) and a uniformed, sworn, civilian body, of trade and businessmen known as the Home Defense League. In the event of an emergency, the members of the Home Defense League performed the duties of special officers. The hope was that the Reserves would become equally trained, as efficient as the regular force, and that the young men would eventually join the Department.

After his term of Mayor ended (December 31, 1917), Mayor Mitchell enlisted in the U.S. military, serving as a pilot in the Army Aviation Corps in the rank of Major. “He was a vigorous athlete, a crack revolver shot, and an adept at exercises requiring strength and agility.” In flight training at San Diego, California, he “broke all records for quickness in learning to fly and for exploits in the air.” On July 6, 1918 while in flight near Lake Charles, Louisiana, Major Mitchell’s plane began a nose dive and he was ejected from the plane before striking the ground. Former Mayor Mitchell’s body was returned to NYC. Born in 1879 in the Fordham section of the Bronx, he attended Fordham College, and Columbia University for his Doctorate of Law. Mayor Mitchell is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, the Bronx.

Placed in charge of all of the various units of the Police Reserves, including aviation, was police Inspector (Insp.) John F. Dwyer. By June 1918, Insp. Dwyer was attending local preparedness meetings throughout the City, informing residents of the steps taken by the Department in the event of major incidents, including air raids.

In another step towards raising the level of preparedness and sense of nationalism, the Reserves established the “Order of Liberty,” a “high order” within the Reserves which was created for those, who had served six months and exhibited “distinctive acts or service,” and demonstrated outstanding performance in: “attendance, training, interest, aptitude, service efficiency, small arms scores, personal appearance and meritorious work.”

Under the supervision of Insp. William O’Brien, each police precinct station-house made preparations to act as a headquarters for the Home Defense League in their area. Medical and other emergency supplies were stored in each station-house which would serve as triage centers in the event of a widespread calamity. The League and the air reserves, comprising the Police Reserve Force, were the City’s answer to the federal government’s call for preparedness.

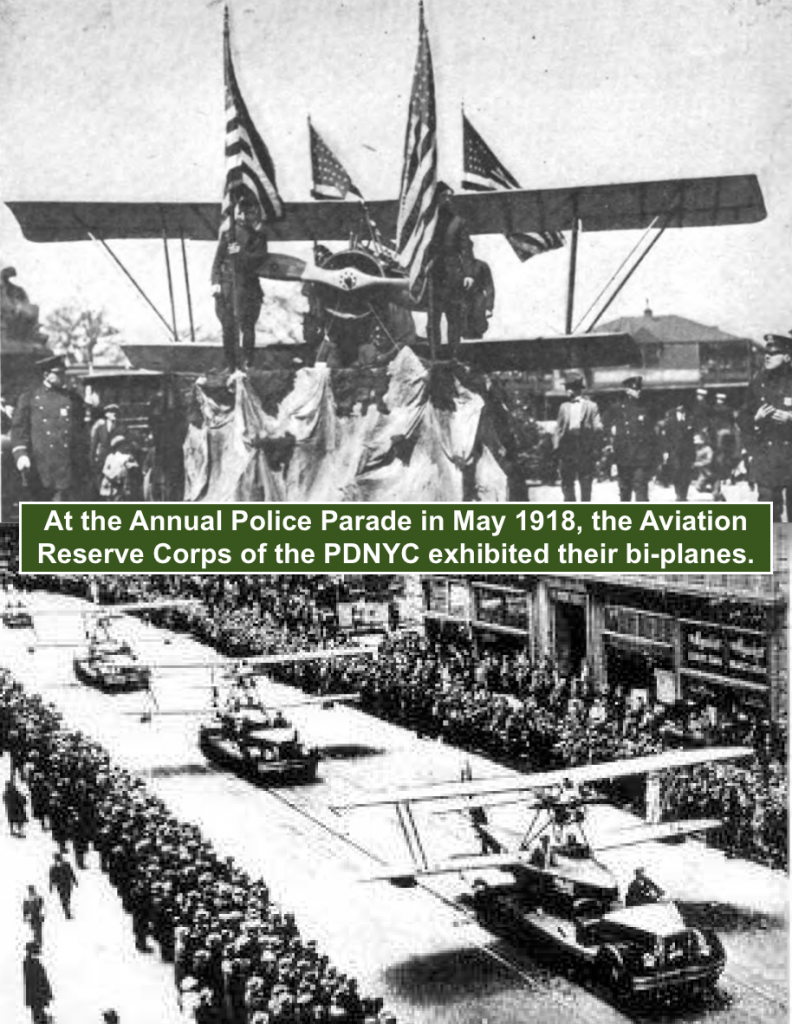

In March 1918, SDC Wanamaker announced that 100 men of the Police Reserves were to begin training as aviators. The nature of the “Aviation Reserve Corps” was to be an aerial defense unit, the functioning of which, after the conclusion of the war, was to patrol the sky for violators of aerial traffic laws.

At the Annual Police Parade in May 1918, the Aviation Reserve Corps of the PDNYC exhibited their bi-planes.

The War in Europe Comes to Our Shores

On June 3, 1918, the U.S. Navy Department issued the following statement: “The Navy Department has been informed that three American schooners have been sunk off this coast (New Jersey) by (two) enemy submarines.” The following day, PC Enright issued the following order: To “All commanding officers of the Police Department: All display lights, advertising signs, or special illumination throughout the city, including the seashores, will be discontinued until further orders. This will not include city lights. In office buildings and dwelling houses where lights are used, shades will be drawn where it is possible to do so. Notify all concerns immediately.” Reports of submarine sightings, and vessels sunk off the coast of New Jersey (NJ), near New York, became more frequent in the days and weeks that followed.

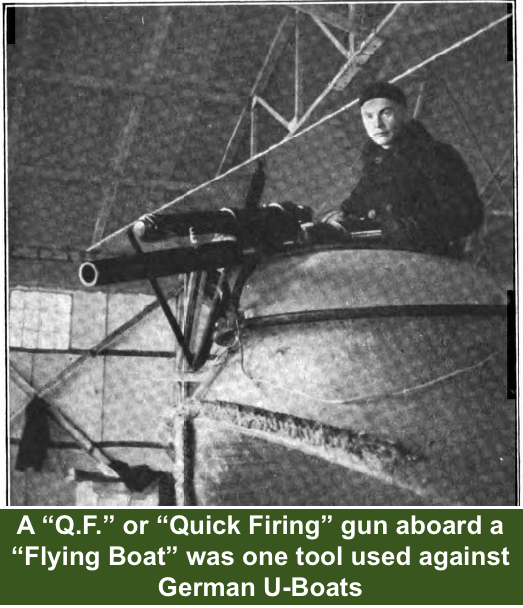

Dirigibles (large lighter than air passenger balloons), large “flying boats” (amphibious airplanes) and smaller spotting planes were used to patrol the coast. Some of the larger planes were used to deploy depth charge bombs in the areas where submarine activity existed. The photo below depicts a machine gun, and gunner, aboard one of the flying boats.

The fear that aeroplanes, as was already the experience of the citizens of England, could be launched from U-boat submarines was realized in the region. These amphibious planes would not submerge, but would be transported afloat, on the decks of the subs, to within striking range of the cities and then launched to attack. The world became a much “smaller space” with the reports of the ability of aircraft to cross the seas and launch from naval submarines. By June 1920, more concrete information had been learned about the use of naval vessel-launched aircraft. Folded-wing aircraft were being tested aboard ships, a more practical vessel than submarines. Germany had declared its intention to create a submarine blockade of US ships from the Gulf of Mexico to the St. Lawrence River, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

For two years, the fear of cargo and passenger ships sunk by German U-boats as they approached the western coast of Europe had been realized. The sinking of ships containing hundreds of thousands of pounds of cargo caused a backup of ships in the eastern ports of the USA, as well as the cargo trains that needed to unload their cargo at the docks. “Economic instability” was added to the list of reasons for President Woodrow Wilson’s cabinet to recommend that the USA join the war.

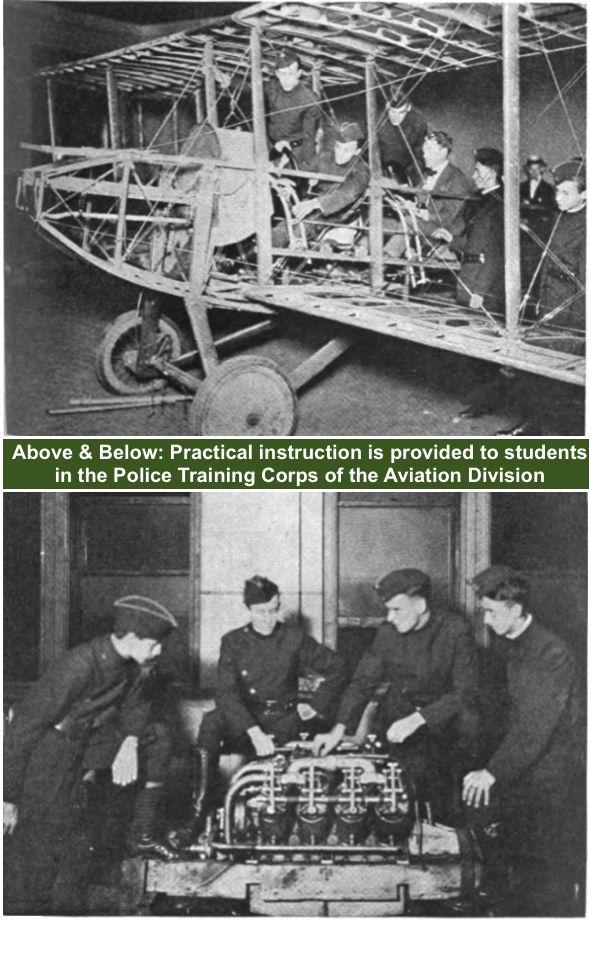

1918; The “Police Training Corps” of the Police Reserves

In 1918, the Police Training Corps was established to train the Reservists, including the aviators. According to one source “Several hundred young men have enrolled in the Police Training Corps, from nearly all occupations in the city, for the instruction and training given. Some are receiving military training while others are receiving aeronautical instruction, the latter being financed by SDC Rodman Wanamaker.” The Aeronautical Training Course including the mechanics of aviation and planes, flying, and radio communications.

In addition to the aeronautical-related topics, the training was believed to benefit society, and the war effort as it trained young men, who otherwise may have run afoul of the law, in practical skills. In addition to the formal curriculum, cadets were instructed in swimming, wrestling, fencing, lifesaving, baseball, handball, and other athletic activities. There was no cost to taxpayers in connection with the school as funds and equipment were donated.

In addition to the aeronautical-related topics, the training was believed to benefit society, and the war effort as it trained young men, who otherwise may have run afoul of the law, in practical skills. In addition to the formal curriculum, cadets were instructed in swimming, wrestling, fencing, lifesaving, baseball, handball, and other athletic activities. There was no cost to taxpayers in connection with the school as funds and equipment were donated.

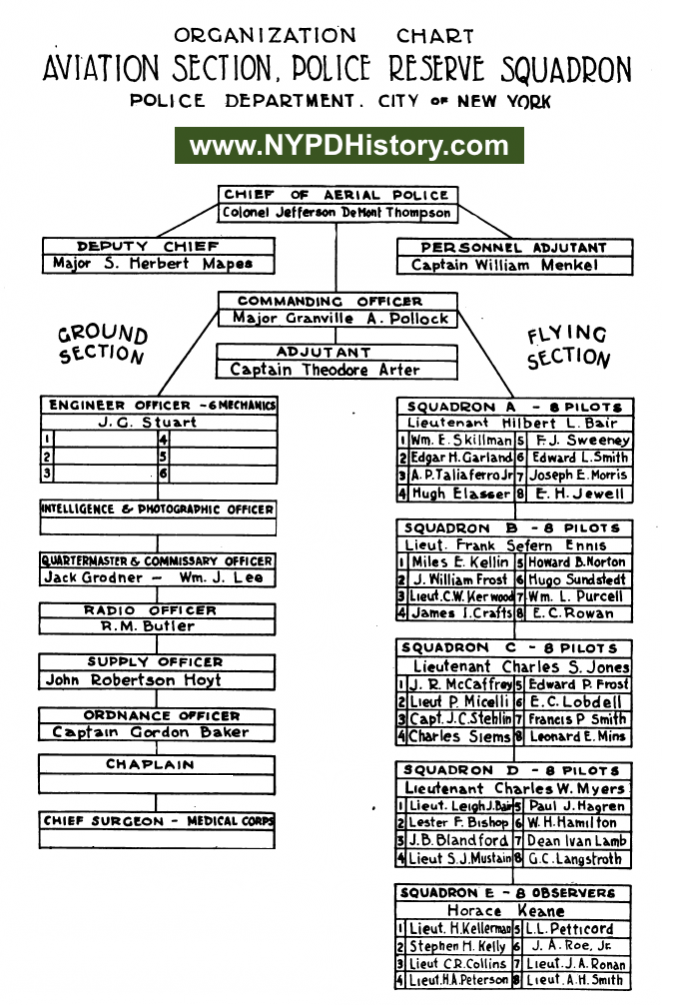

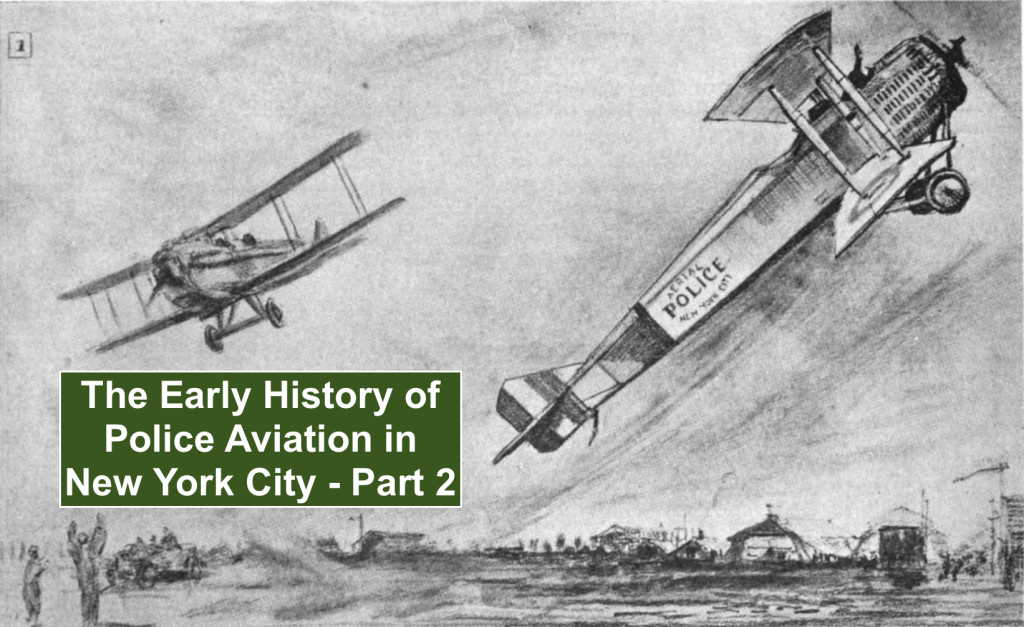

At a luncheon of the Aero Club of America, held on December 1, 1918, PC Enright announced the organization of an “Aviation Section” and turned to another well-known aviator, Colonel Jefferson De Mont Thompson, to lead the PDNYC’s “Aerial Police” as “Chief,” and claimed the Aviation Section of the PDNYC to be “the first” such entity in “the world.” Mr. Thompson was an aviation enthusiast since 1905, a founding member of both the Aero Club of America, the Automobile Club of America and nationally recognized expert in traffic.

1918; The Aerial Squadron (Aero Squad) of the Police Reserves

According to the Annual Report of the Police Department of the City of New York (ARPDNYC) for 1918 (published in January 1919), 216 Police Reservists, described as “men who were deeply interested in police work and who were optional candidates for appointment” as police officers, were selected for the Aviation Division of the Police Reserves. The aviators selected for the Aerial Squadron of the Police Reserves were expert aviators, many of whom served as military aviators. A Board of Governors would oversee the training and conduct of the Reservist Aviators. In addition to the Aerial Squadron, Machine Gun Squadrons, comprised of Reservists, were trained and stationed at bridges, docks, and other sites critical to the infrastructure of NYC.

On February 3, 1919, it was reported that the Aviation Section of the PDNYC would be comprised of volunteers only and that the section would follow the formation of the aero squadron as prescribed by the federal government. A squadron comprised of 20 officers, which included 12 pilots, medical, technical and executive officers. According to the federal government, the total personnel of an aero squadron was 154 non-commissioned enlisted men and officers. By complying with the federal rules, the New York Police Aero Squadron was to be “of military value and will set the standard for police aviation sections, which other cities, no doubt, will organize in the near future.”

The section was to be trained and ready in the event of riot, conflagration, police activity in connection with the waterways as well as to be observers. A catastrophe on October 4, 1918, in nearby Morgan, Middlesex County, NJ, reinforced PC Enright’s position that the Department perform the important function of aerial observation.

The catastrophe was the explosion of a munitions plant, at the Gillespie Plant in Morgan, the effects of which were felt in NYC. It is estimated that 1,000,000 pounds of ammonium nitrate, 30,000,000 pounds of explosives and and 1,000,000 loaded shells left dozens of craters, the largest 30 feet deep, 140 feet wide, and 150 feet long. The initial cause was attributed to sabotage, something PC Enright believed could have been detected with aerial surveillance.

In the event of an air raid, PC Enright advised the public that “siren horns or whistles will be sounded continuously for ten minutes. When this signal is given every one should immediately open the windows of their homes and offices and go at once to the cellar of the premises.” As for the PDNYC and the Home Defense League, upon an air raid signal, plans were executed. These plans included relieving workers from their jobs to serve the public. Ambulances and trucks were pressed into service while tradesmen, businessmen, and women, were to offer specialized assistance.

The plans also called for fifty aeroplanes, to fly from the aviation fields in Hempstead, Long Island (LI) to patrol the waters between Montauk Point and Coney Island. Eight planes were to fly in a “V” formation, each armed with bombs and machine guns.

In January 1919, Majors S. Herbert Mapes (Deputy Chief) and Granville A. Pollock (Commanding Officer) joined Colonel Jefferson De Mont Thompson in the Police Reserve Squadron of the Aviation Section.

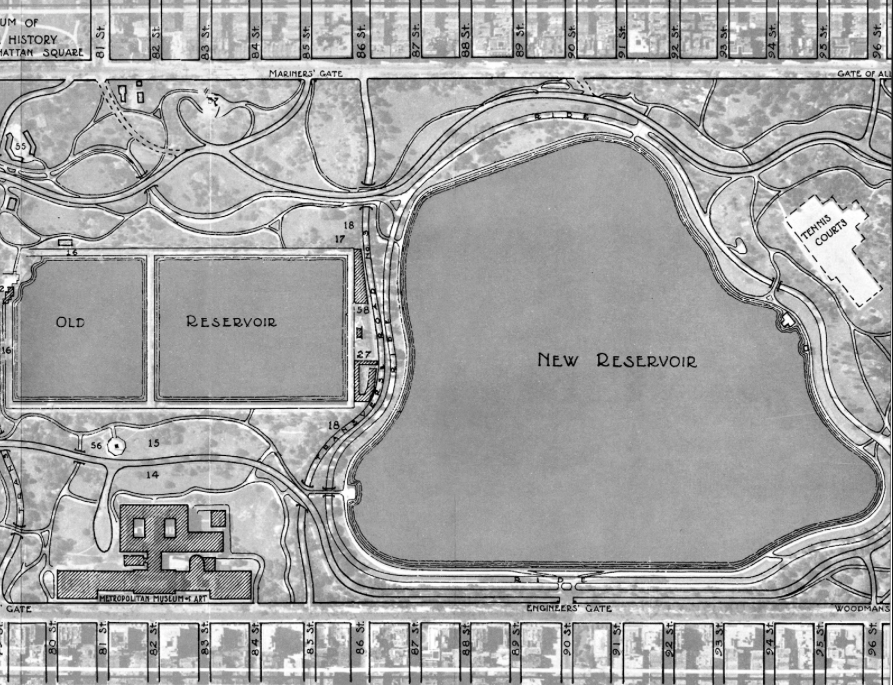

On March 17, 1919, Insp. John F. Dwyer announced that the “old reservoir” in Central Park would be drained and used as a landing strip for the PDNYC. Hangars for the aeroplanes were built on a filled-in strip of land on the Hudson River at West 86th Street.

On April 2, 1919, at a meeting held at Police Headquarters, 240 Centre Street, Manhattan, it was decided that twenty airplanes, equipped with wireless radios and machine guns, would “constitute the first aviation branch of the New York Police Reserves, under the charge of Major Pollock. It was announced that “two land planes and two flying boats have (had) already been secured and more machines will soon be forthcoming.”

1919; The First “Official” Aviation Police “in the world”

On April 5, 1919, the first group of aviators were sworn into service. All twenty men were veterans of the war. PC Enright, addressed the group and stated “You are the advance guard of aviation and you have come to the right place. I am sure you will be useful.” said the Commissioner. PC Enright continued “In my opinion, it is a most auspicious day for the police reserves and for the Police Department of New York. The day of the airman has indeed arrived – much sooner than anticipated.” PC Enright announced that landing fields had been obtained at Sheepshead bay (Brooklyn), Van Cortlandt Park (Bronx), and Governor’s Island (New York Harbor). The aviators made their first public appearance wearing their sky blue uniforms at an aerial event held in Atlantic City, NJ, on April 14, 1919. This uniform would remain until August 1924, when a dark blue uniform, similar to that worn by the regular police officers of the PDNYC, was adopted.

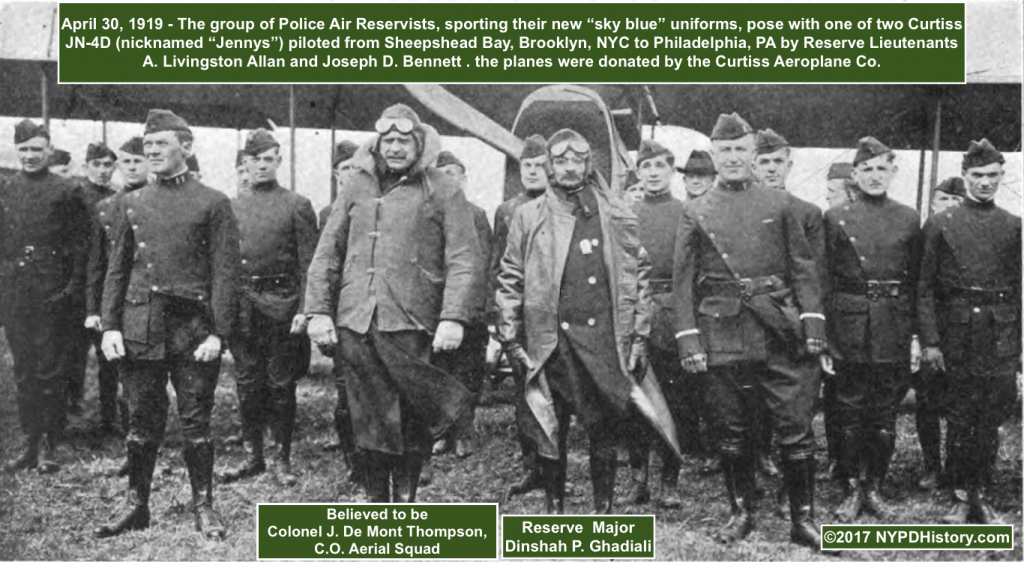

Upon the completion of training, the initial flight of the Aviation Section of the Police Reserves took place on April 30, 1919, when two Curtiss JN-4D training biplanes took off from Speedway Park, Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn for Bustleton Aviation Field, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. NYC Mayor Hylan proclaimed that the aerial police of the PDNYC were the first to exist in any city, and the flight that day to be the first “official one of any police department in the world.”

The planes were piloted by two veterans of the Great War, Lieutenants A. Livingston Allen (accompanied by Police Inspector John F. Dwyer) and Joseph Bennett (accompanied by Reserve Major Dipshah Ghadiali). In March 1919, Major Ghadiali was appointed by SDC Wanamaker to oversee the Police Reserve Aviation School.

Major Ghadiali delivered a letter from NYC Mayor Hylan to the Mayor of Philadelphia. In part, the letter read “It seems proper that the first flight of aeroplanes, in the service of the Police Department of this city, to Philadelphia should be the occasion of mutual felicitations…This flight bids fair to mark the dawn of a new era in police progress. It does not require much imagination to force great possibilities in the use of the airplane in connection with police work.”

In April 1919, Major Pollock, Commanding Officer of the Aerial Police, PDNYC, returned from Bordeaux, France with a Salmson Scout bi-plane en route to a waypoint for transportation to America. It was reported that, as a result of the publicity surrounding the PDNYC’s lead in organizing an aerial police, and the demonstrations performed in France and the USA, cities around the world as far away as Singapore, Brazil and the Philippines were following the PDNYC’s lead. The Salmson biplane (example depicted below) was delivered and readied for service in NYC in April 1920.

On April 5, 1919, the “Ace of Aces” of the Great War, the renowned aviator Edward V. Rickenbacker, was presented a gold medal by the Automobile Club of America. Capt. Rickenbacker is credited with “downing” twenty-six enemy planes. Colonel De Mont Thompson, Major Pollock, and Capt. Mapes addressed the crowd and announced that Rickenbacker accepted the position of Lieutenant-Colonel on the Aviation Section and donated two aeroplanes to the PDNYC. Other famous “Aces” of the Great War who resided in the City, were invited to join the Reserves. The Ace with the next highest number of credited “downs” was Major James A. Meissner, with eight.

On April 11, 1919, sixteen aviators took off from the Hazelhurst airfield (Garden City, LI) with Manhattan Island in their sights. Shortly after 2:00 pm, the Handley-Page and Fokker aeroplanes (Note: the Fokker was seized from the Germans and was flown by Captain A.D. Simonin and Lieutenant G. Stewart) “bombarded” Manhattan Island with Liberty Loan advertisements.

On the same date, it was announced that the new municipal airfield in Atlantic City, NJ was designated as the training field for the Aero Squadron of the PDNYC and that plans for a training school were under consideration.

Weeks later, on April 14, 1919, it was reported that twenty aviators of the Aviation Branch of the PDNYC were soon to take to the air doing “regular duty” under the supervision Major Pollock. The aeroplanes, equipped with Culver brand “wireless telephones,” permitted communication between the aviator and the U.S. Navy as well as Police Headquarters. One of the immediate duties of the Aviation branch was to photograph, in scale, the entirety of the Greater City of New York and to identify strategically located fields for aircraft.

During the summer of 1919, NYC communicated with other cities, such as Chicago, to formulate ideas for legislation in regard to laws applicable to aviation. One article, relates that municipalities learned their lesson from their experience in not moving with the speed required to keep up with the growth of automobiles years earlier. Twelve suggested points for legislative action were printed in an article in the New York Times, published on August 25, 1919. These included, in part: police department (PD)-required registrations, PD-issued permits for “trial-flighted” (tested) aircraft, use of approved airfields, permitted flight zones, permitted flight altitudes over cities, rights-of-way, etc.

1919; The First Female Police Aviator & the First Female “Sky Cops”

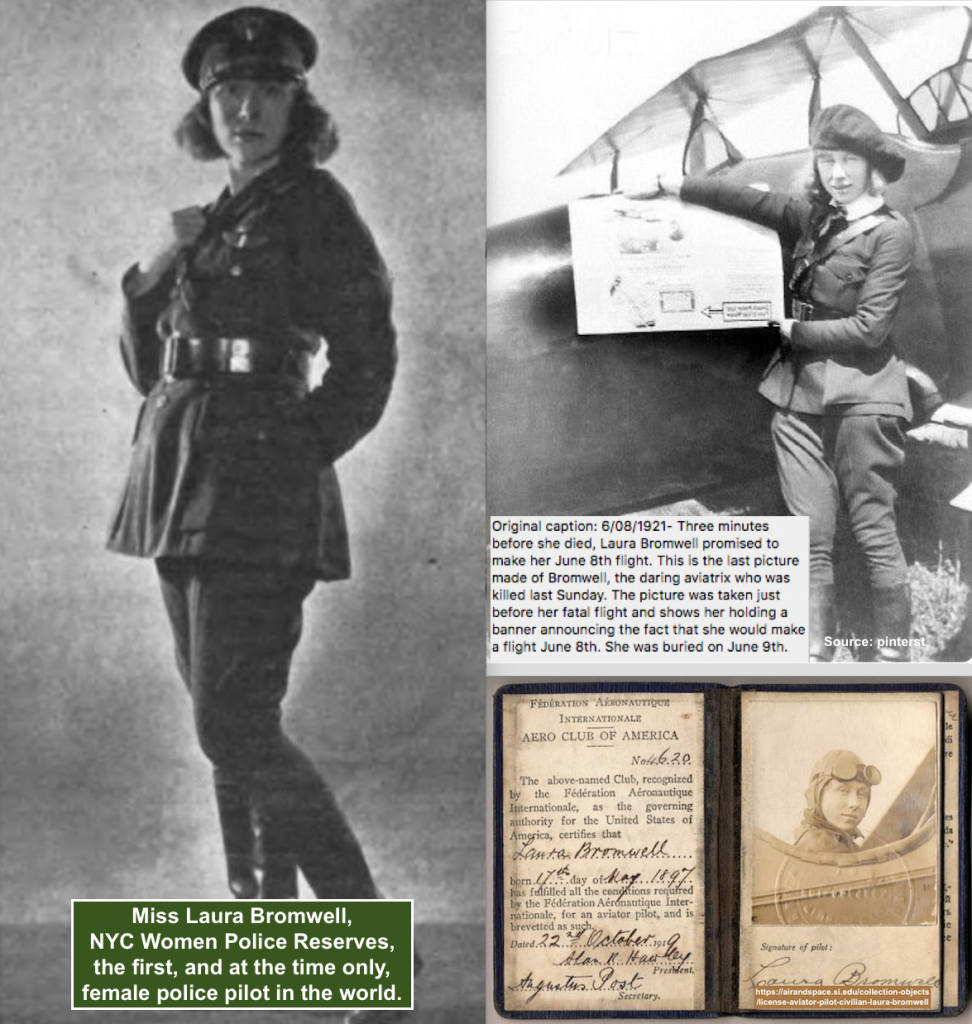

In October 1919, the PDNYC announced that they sought to add women to the “sky cops.” Advertisements and newspaper articles announced that thirty women, who could pass physical and mental tests, and who were between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five, were sought to join the 134 men (described as professional aviators all of whom served in the armed forces) attending the Aviation Corps School, located at 156 Greenwich Street, Manhattan. This building was previously used by the PDNYC as the Second Precinct Station-house. Upon successful completion of a physical examination as prescribed by the U.S. Army, candidates were required to purchase their uniforms and books during their time at the training school. Instruction in auto mechanics, radio operation, rigging, and flying was provided. The U.S. Navy loaned the Aviation Corps School two amphibious planes which were kept at Port Washington, LI.

Graduates of the school formed the “Women’s Police Reserve” of the PDNYC, under the command of “Mrs. Robert H. Elder.” Two planes, assigned to the men’s unit, and located at Port Washington, LI, would be used by the women’s aviation section. These women aviators were required to pay for their expenses and uniforms. After successful completion of training, their duties were to be “scout work, message carrying and similar functions in times of emergency.”

The first female aviator to graduate the Aviation Corps School was Miss Laura Bromwell, of Cincinnati, Ohio, thus giving her historic standing as the first aerial policewoman in the world. At only twenty-one, Bromwell received her Pilot’s License on October 22, 1919 from the Aero Club of America and became an avid flight enthusiast. On July 3, 1920, Reserve Lt. Bromwell flew from Roosevelt Field, LI to Atlantic City when her plane caught fire. She landed safely in Sea Girt, NJ. Lt. Bromwell performed daring “stunts” in many states for large crowds. In early June 1921, Lt. Browmell received a gold medal from the Police Reserves and received a promotion to the rank of Captain. Days later, on June 8, 1921, when performing a stunt 2,000 feet above Garden City, LI, witnesses reported seeing her body hanging outside of the plane, upside down, held only by straps. As the plane descended to the ground, Capt. Bromwell was unconscious. It was reported that “every bone in her body was broken.” Insp. Dwyer was charged with the responsibility for the preparations of her funeral.

In light of submarine activity, attacks, and anxiety of Americans, it is clear that Mayor Hylan, PC Enright, their appointees, volunteers, and the PDNYC as a whole, were correct in proceeding in the most expeditious manner possible – the formation of a Reserve Corps of experienced military pilots and civilian aviators – to protect the City and its neighbors. Perhaps former Patrolman Charles Murphy’s words didn’t fall on deaf ears, or, perhaps, the idea, now coming from “the top” of the PDNYC was now “brilliant.” Sadly, Murphy’s influence does not appear to have been recorded, but it cannot be denied that without Mile-A-Minute Murphy’s initiative, in-uniform exhibitions, and public statements, attention to aerial police service may not have occurred when it did.

Click here to read Part 3 of this series!

![]()

“www.NYPDHistory.com

Where History is Colored

With Facts, Not Photoshop”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.