![]()

Introduction

Prior to the Great War (1914-1918) the Police Department of the City of New York (PDNYC) adopted, for only a decade, the use of motorized vehicles (motorcycles and automobiles). The concept of policing the sky over New York City (NYC) with police officers in “aeroplanes” had not yet been officially considered. This quickly changed with the onset of the Great War, and prior to the United States’ 1916 entry in to the conflict. The realization that NYC, and America, was at risk from a variety of entities, including anarchists, rioters, German submarines off the coast of NYC and New Jersey (NJ) initiated a nationwide movement to prepare the homeland for invasion, or entry into the war. As the eastern coast of the United States of America (USA) was closest to Europe, and German naval vessels, the risk, and preparations, were heightened. The USA did not have a military air force, so police departments began to consider filling the void.

The first “first” will give some historical context. According to an article, dated March 24, 1913, on/about March 10, 1913, Harry M. Jones, “a youthful aviator from Providence, R.I.” flew at an altitude of 2,000 feet, from Boston to New York, carrying a cargo of U.S. Mail. Forced to land in Mamaroneck, New York (NY) (a Westchester County village, on the Long Island Sound), on Saturday, March 21, in the light of a bright moon, he took off in his Burgess-Wright bi-plane for Governor’s Island. This was the first recorded nighttime flight over NYC.

Able to see the Singer, Woolworth, and Times buildings, as well as the “Great White Way” (Times Square), he landed near Flatbush, Brooklyn for the night, after flying for one hour. He approached a residence wearing his “flying suit,” described as “a red stocking hat, padded leather coat, leggings, and goggles” and knocked on the door. The homeowner couldn’t believe his eyes, or Jones’ explanation as to how he arrived, but upon seeing the plane on his property, welcomed Jones after stating “I thought you were a ‘bug’ who had escaped from the funny house, motioning in the general direction of Kings County Hospital.”

How Charles M. Murphy Became Forever Remembered As “Mile-A-Minute-Murphy”

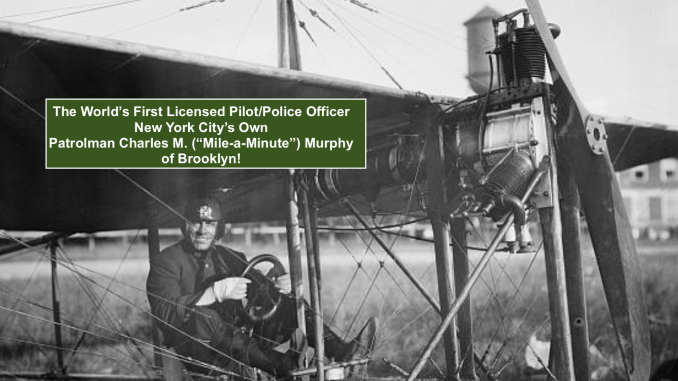

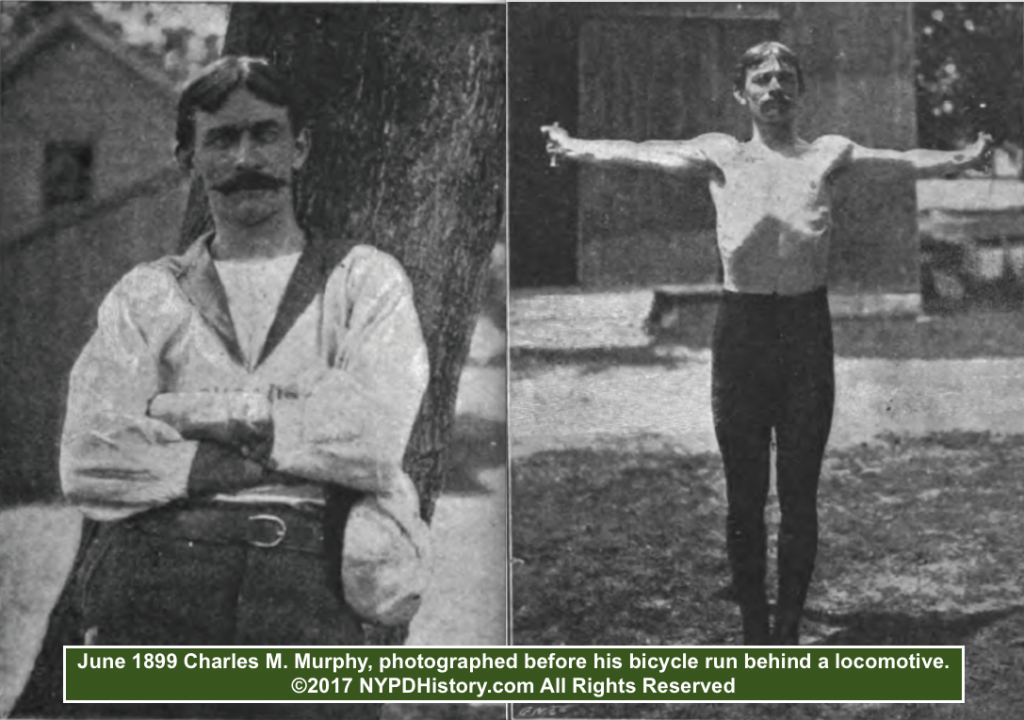

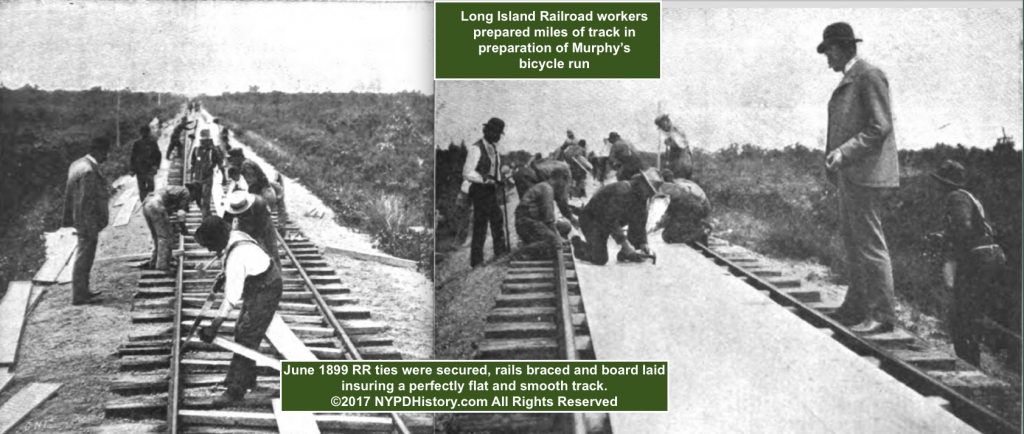

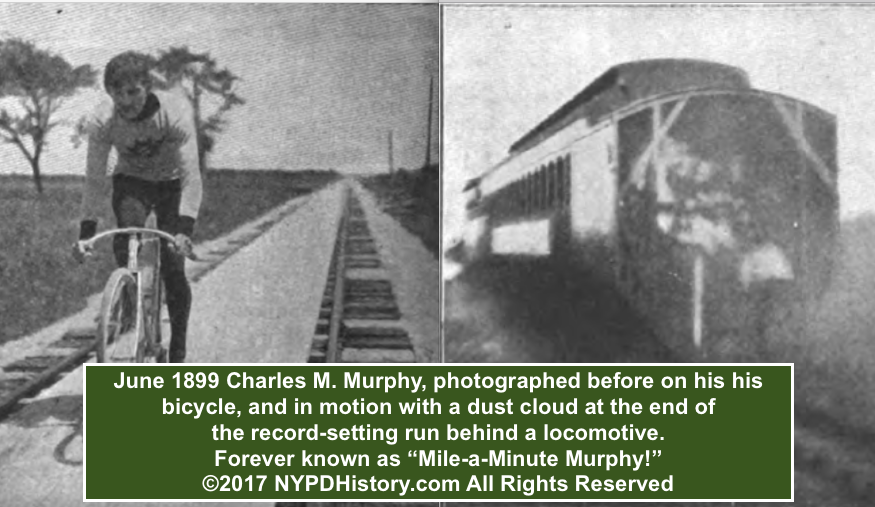

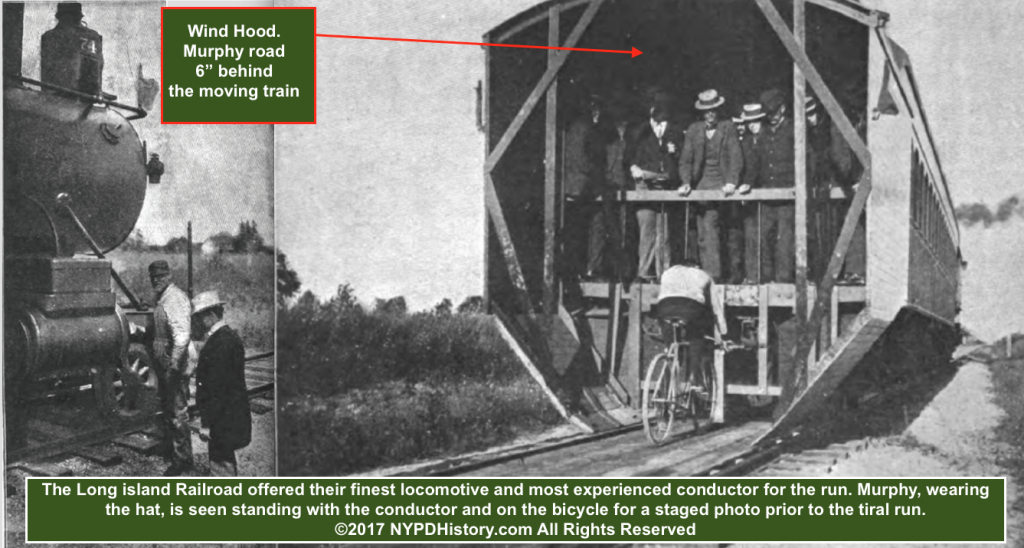

The PDNYC’s history of aviation must begin with the plight for flight of a single Patrolman (Ptl.) named Charles M. Murphy. Ptl. Murphy was better-known known as “Mile-a-Minute Murphy,” but not for his skills as an aviator. Murphy, a risk enthusiast, entered the cab of a runaway passenger train and stopped it just short of crashing. He also parachuted from a blimp, and contacted various railroads across the country to permit him to be paced by a locomotive for five years. Fortunately, a friend obtained a position with the Long Island Railroad and facilitated the well-publicized stunt. On June 30, 1899, the Brooklyn resident, well-known as a track and bicyclist champion, bicycled for one mile behind a Long Island Railway locomotive and travelled the mile in just under one minute (5,280 feet in 57.45 seconds, by one account).

To eliminate any wind drag or turbulence trailing behind the speeding locomotive, a wooden hood was constructed behind the rear car. The hood was over eleven feet long and the area Murphy rode in extended six feet from the rear. The design of the hood closely resembles the hoods on the rear of today’s tractor-trailers seen on highways across America. During a trial run, timers, judges, and observers stood on the rear platform of the train car, under the hood. They held silk handkerchiefs, observed the behavior of the air, and noticed no unusual drafts or vortices. To avoid the potential for Murphy to be adversely affected after the mile run, when he trailed off behind the locomotive, Murphy was hoisted onto the moving train by the men.

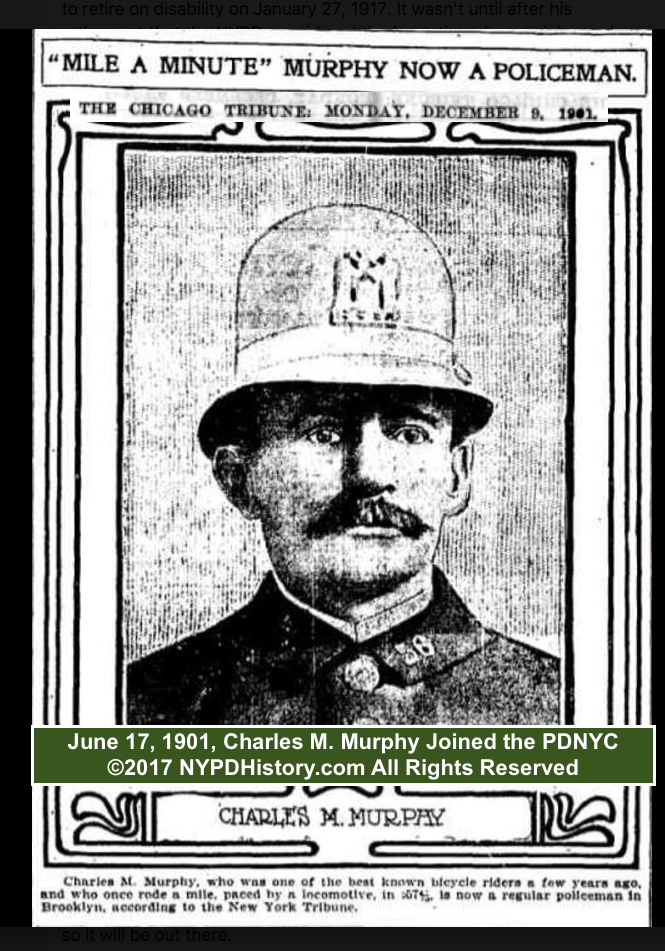

Mr. Murphy Becomes Patrolman Murphy

Charles M. Murphy, appointed to the PDNYC on June 17, 1901, was assigned over his career to precincts in Brooklyn, Manhattan and Queens. In Queens, he was assigned to the 278th Precinct Station-house in Jamaica, but his main interest in aviation. In 1904-5, Patrolman (Ptl.) Murphy was one of several Patrolmen involved in litigation against Police Commissioners (PC) William McAdoo (1904-1906), and Theodore Bingham (1906-1909) in connection with their assignment to perform the duties of a Detective while a Patrolman.

1914; One Patrolman’s “Plight for Flight“

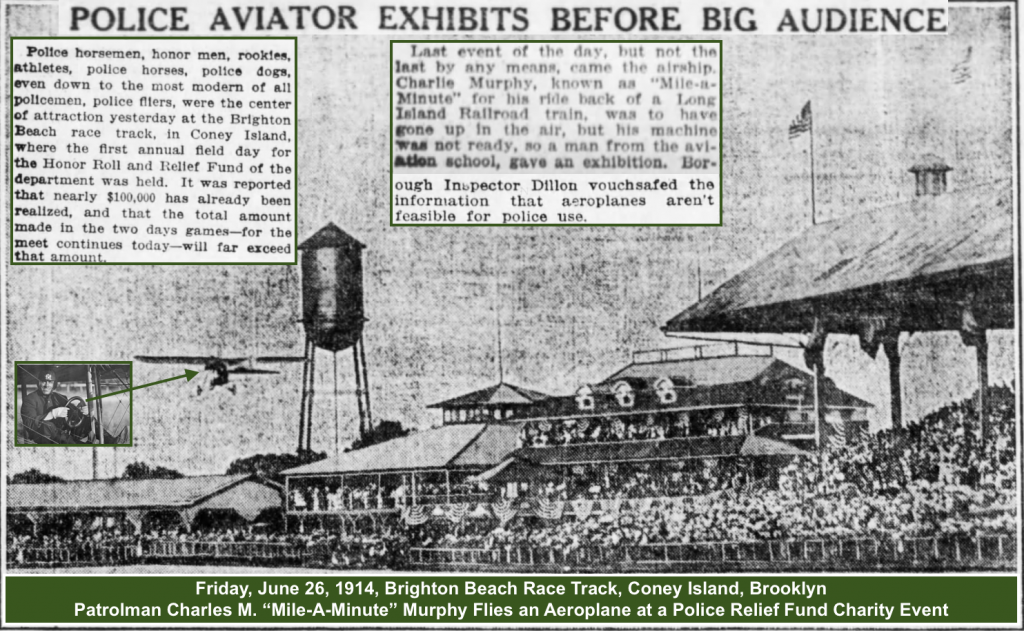

An article published in the New York Times, on August 11, 1914, described Murphy as the “only policeman in the USA, and, so far as it is known, the only one in the world, who has learned to pilot a heavier-than-air flyer.” The article indicated that Murphy became an aviator (licensed pilot) to entertain crowds at the annual Police Exhibitions, held at the Brighton Beach Racetrack, Brooklyn, which were held to raise funds for the Police Relief Fund (to benefit the families of officers killed in the performance of their duty – the equivalent of today’s “Widows and Orphans Fund”).

To accomplish the goal of participating in the exhibitions, in 1913, Ptl. Murphy received a pilot’s license. In 1914, Ptl. Murphy received training from a skilled aviator, Giuseppe Bellianco, at the Moisant Aviation School, Garden City, Long Island, on a 50 horsepower Moisant monoplane. The lessons consisted of six one hour sessions. Ptl Murphy was on an official leave of absence, granted by Police Commissioner (PC) Arthur Woods during his training. After a few lessons, Ptl. Murphy declared “I’m ready now to risk my neck with her” and proceeded to fly over Manhattan and “buzz” the gilded dome of police headquarters at 240 Centre Street.

On June 27, at the 1914 Police Exhibition, held at the Brighton Beach Racetrack, Brooklyn, Ptl. Murphy became the first PDNYC police officer involved in an aerial collision. While taking off on the field at Brighton Beach, Ptl. Murphy’s plane struck the rear of a motorcycle operated by another officer, causing damage to the motorcycle and the plane’s propeller. Both officers escaped with only memories as there were no injuries.

In the 1914 photo (below), by famed photographer George Grantham Bain, depicts Ptl. Murphy wearing a PDNYC-issued fur cap with his PDNYC-issued cover device. It was reported that Ptl. Murphy refused to wear a safety helmet or pilot’s uniform as he was proud to appear in his uniform and fur cap. Apparently, PC Arthur Woods (1914-1918), also an aviation enthusiast and, in 1918, a PDNYC Reserve Lieutenant-Colonel/Pilot, did not mind Ptl. Murphy appearing in uniform.

As for the practical use of an airplane in police service, the New York Times, in an article, published on August 11, 1914, quoted Ptl. Murphy, as having stated:

“the airplane is bound to suggest itself to apprehending criminals. But I venture to say that the police will not avail themselves of it until some crook, or clever band of crooks, demonstrate to them how they are to use it. There isn’t any doubt in my mind that New York City before very long is going to hear of a big robbery in an aeroplane, made possible simply because the men who do that sort of work are the cleverest and know joe to make use of the very latest inventions.”

Ptl. Murphy drew a relevant analogy to the PDNYC’s hesitation in adopting the use of automobiles. The article closed quoting Ptl. Murphy as saying “I believe the Police Department should consider the use of aeroplanes immediately. The Army and Navy have demonstrated their practical value…it would be a great protection for the Greater City in many ways, if it was surrounded by aviation fields from which an airplane could start in pursuit of criminals fleeing in automobiles.”

On July 19, 1916, Ptl. Murphy had his “wings clipped” by the department when he, while assigned to the 278th Precinct in Jamaica, was charged with: 1) failing to return promptly to a police booth at the conclusion of an investigation, 2) failing to return to a police booth and telephone a report, and 3) failing to make an entry in a record. Coupled with his decade earlier writ of mandamus against the department, perhaps Ptl. Murphy’s career was viewed differently within the department than by the public.

The PDNYC Missed the Flight

In December 1915, the Aero Club of America, the preeminent, and perhaps only, club devoted to aviation in the country, offered to assist in raising funds for the National Aeroplane Fund to fund the training of pilots, and purchase of 2,000 aeroplanes for the defense of the country. NYC had raised more than $20,000 through subscriptions towards the fund, yet no training, or planes were on the horizon. In the coming years, the Aero Club would be key to the PDNYC’s establishment of aviation police.

Another advocate for the use of aeroplanes (as well as submarines) in the defense of the nation was the inventor of the famous Lewis Machine Gun, used extensively by the entente (allied) forces against the belligerents (Germany) during the Great War. In an article, published in the New York Times, on June 11, 1916, Colonel Isaac Newton Lewis, US Army, retired, concluded that, after years of his travels abroad studying the military readiness of other countries, the USA was “nearly ten years behind other great powers both in the proper appreciation of the need of modern weapons and in the development and constructions necessary to meet this need.”

While Ptl. Murphy’s prophecies seemed logical, and advice sage, like the plight of many Patrolmen with the best of intentions, and with “great ideas,” the upper echelon of the PDNYC did not immediately heed his advice. On January 29,1917, Ptl. Murphy, as a result of a second broken leg, was retired from the force at an annual pension of $549. The career-ending accident occurred on September 3, 1916, when Ptl. Murphy, on-duty and riding a department motorcycle, collided with an automobile on the Manhattan Bridge. Ptl. Murphy sustained three fractures in his left leg and was hospitalized for nine weeks before being retired by the department.

In 1921, Murphy petitioned the city for an increase in his annual pension to fifty percent of his final salary. The petition was granted, was vetoed by the mayor, and appealed to the NYS Legislature. The bill passed the legislature on April 16, 1921.

Now “Mr. Murphy,” Charles did not give up his efforts to encourage the PDNYC to create a first-class aviation corps. Mr. Murphy also foresaw the need for aviators to patrol the coast for ship or plane wrecks and to assist the military in defending the country. Although he never received any official credit from the department, Ptl. Murphy’s influence and place in the history of police aviation cannot be overlooked or denied.

Note: There will be several “firsts” identified in this series of articles on the history of the early use of aircraft by the PDNYC. As is the case with any examination, the “firsts” are defined as the “earliest information found to date.” As is the case with politics, in the context of claims for “firsts,” the reader will find that, for one reason or another, the claims sometimes seem to ignore the facts and history. A list of “firsts” will appear at the end of this multi-part essay.

![]()

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.