![]()

A century ago, the Police Department of the City of New York (PDNY) had within its ranks a officially sanctioned force known as the “Junior Police Force” (JPF). The JPF existed from August 15, 1914 to July 9, 1918. The JPF began in the Fifteenth Police Precinct with a group of twenty-five boys. At the time it was disbanded, it spanned eighty-nine precincts, and all five boroughs. In 1918, the JPF numbered approximately 6,000 boys and was three-fifths the size of the regular force, which had approximately 9,648 sworn members.

The 100th Anniversary of the JPF passed without mention and little is known by today’s historians about the brave boys who wore its shield. More importantly, and disconcertingly, there are no official records of three Junior Police Officers (JPO), aged eleven, twelve, and thirteen, who gave their lives in the performance of official duties. There is no written record or memorial anywhere conveying their stories or bearing their names. The incidents, and their memories, are long forgotten. However, this author has pored over dusty journals, scrutinized old photos of those small, chubby faces which were not yet hardened by life’s hard experiences, and has pieced together the first-ever comprehensive look back at their tales.

Stars Aligned for Creation of the JPF:

The forty-year period straddling the turn of the nineteenth century was marked by the arrival of a tremendous swell of immigrants from Europe. Many entered through, and remained in, New York City (NYC). During that period, ninety percent of Eastern Europe’s Jewish population emigrated to the United States. To a great extent, these immigrants settled in NYC’s Lower East Side. These newcomers brought their languages, customs, traditions, and criminal enterprises to the city. The majority lived in poverty and, through hard experience in their countries of origin, nursed a deep-seated distrust of authority figures, particularly police. The PDNY faced new challenges in dealing with these new immigrant groups.

In 1914, as America watched the nations of Europe enter the Great War and anxiously pondered the possibility of joining the fray, a strong sense of nationalism swept NYC and the country. It is likely that the JPF’s creation, and rapid growth, was fueled by this sense of nationalism.

Arthur Woods, was a social-minded, forward-thinking Police Commissioner (PC) of the PDNY, who looked for new ways to reach out to immigrants. Coincidentally, the Captain (Capt.) of the Fifteenth Police Precinct, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, was looking for a way to channel the energy of the rambunctious, mischievous boys in his precinct. The crap-shooting, cigarette-smoking vandals merely needed attention, he thought. So, when a few neighborhood boys, including Harry Rodman and Julius Morofsky, approached him and told him that they conceived an idea to engage the youth of his precinct, he quickly embraced them.

The timing could not have been better. PC Woods embraced the concept and would, in the near future, formally adopt the boys’ Junior Police Force into the PDNY.

A Pledge + 15 Cent Shield = Success!:

“Commissioner Woods recognizes in the child the first and primal factor in good government. Children go wrong not because they are inherently bad; they are not. They are bad – at least they are unruly – generally through no fault of their own. They go wrong chiefly because their attention is not absorbed by the good.”

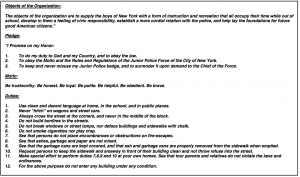

Capt. Sweeney, working with the boys and the police department, laid out the framework and foundation for the new force. On August 15, 1914, the PDNY and the JPF adopted Objects, Pledge, Motto, and Duties for the newly formed organization. (See Insert below)

A compilation of monthly reports of JPF units, added “The duties of the Junior Police are strictly confined to the above list. They do no regular police work, but they are expected to aid the regular police by complying with the duties and through their efforts make other boys respect order.”

Boys, aged eleven to fifteen, could apply for membership at their local precinct, and after promising to obey the Pledge (which they were required to recite from memory), Motto, and Duties, would sign a membership card, which was maintained in the local precinct.

Members were required to attend meetings and drills. If their attendance and behavior were perfect, they were issued a shield. A deposit of fifteen cents was required.

Violations of the rules of conduct would result in the forfeiture of the shield and removal from the JPF. As a matter of fact, one of the two original members of the force fell from grace and was removed. Julius Morofsky, “after several trials,” was “dismissed in disgrace.” No record of what shenanigans young Julius committed has survived.

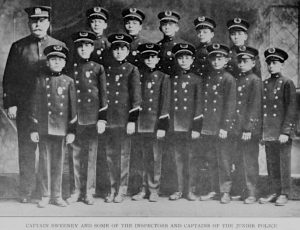

(Photo: New York Tribune which, on October 17, 1915, reported that, on Labor Day of 1914, JPF founder Harry Rodman was appointed “Chief Inspector” of the JPF by Capt. Sweeney)

Newspaper articles, the official publication “Junior Policeman,” and other documents, clearly indicate that the majority of JPOs were Jewish and that temples in the Lower East Side of Manhattan and areas in Brooklyn, supported their local JPF units.

In March of 1915, an article (published in The Bryan Times [Ohio]) described the PDNY’s JPF and its duties, such of which were: “preventing swearing in the public streets,” which included building bonfires, playing craps, smoking, and fire prevention. The article sagely added, “In order to prevent these duties from interfering with their play hours each boy is ‘on’ only a half hour each day.”

The press quickly picked up the story. In April 1915, the Meriden Morning Record [Connecticut], praised Capt. Sweeney for embracing the concept. The article noted that the enforcement by the JPOs resulted in “more justice than hauling an ignorant Yiddish matron into the magistrate’s court where she is likely to be fined ten dollars.”

The article described the hierarchy of the JPF and its four styles of shields noting that the shields were modeled after those of the regular police force and were purchased by Capt. Sweeney himself. The article added that Capt. Sweeney had just one complaint about his pint-sized policemen: “They all want to be Detectives. They all want to ferret out plots.” Though the children were not ready to make those kinds of high-profile “collars,” it soon became clear – to both the PDNY, and the public – that they improved the quality of day-to-day life in the city.

On July 29, 1915, the Schenectady Gazette ran an article proclaiming that the success of the PDNY’s JPF had piqued an interest in a similar force being formed in that city. By this time there were 3,000 boys in New York City’s JPF, which had spread to the City’s boroughs of The Bronx, Queens, Brooklyn and Staten Island. In fact, the PDNY sent JPF Capt. Frank D. Mandel to Schenectady for the summer to act as an ambassador and to help establish a JPF in that city.

An important component of the PDNY’s JPF was its schedule of weekly events that were held at schools and civic sites. One of these activities was “drilling” – as in marching in military-style formations. Perhaps the boys were mimicking what they saw around them as this nation, and others, got closer to entering the Great War. The practice promoted discipline, self-esteem, competitiveness, character.

By the spring of 1916, local precincts of the JPF were called upon to drill at civic events and parades, and to act as a ceremonial unit at police functions. Additionally, some units formed bands that performed at parades, department functions, and officers’ funerals.

In March of 1916, the Daily Standard reported that baseball teams were being formed by JPF units in order to foster “neighborhood loyalty” (and, ostensibly, to keep local boys occupied and out of trouble).

The competitive spirit brought on by public displays of athleticism flourished throughout the city. In June of 1916, JPF of Brownsville Brooklyn organized a carnival in their neighborhood. Athleticism and participation in civic and athletic competitions were important components of the organization, the PDNY, and the city. This legacy contributed to the later formation of organizations such as the New York City Public School Athletic League (P.S.A.L.) and in today’s Police Athletic League (P.A.L.).

Many articles that covered the JPF’s participation in events related to the war effort, including “Loan Drives,” parades, and exhibitions. One such event, in support of the “Battleship Fund,” a grassroots effort to help finance the building of the USS America, was reported in a New York Tribune article, on April 1, 1916. Over 300 boys from the Fifteenth Precinct’s JPF were present. The JPF officers of rank wore uniforms, “the gift of the citizens’ committee of the district.” That night, the committee presented the JPF unit with a silk banner (Insert – Photo) and an American flag. Additionally, JPF Chief Inspector Harry Rodman promoted PDNY Capt. Sweeney to the rank of Sergeant in the JPF.

As time went on, the JPF became more involved, in depth, citywide. Classes such as “First Aid to the Injured” were provided by medical professionals to the JPOs. The city’s Department of Health instructed the boys on matters related to maintaining good health, cleanliness, and sanitary conditions. Familiarizing their families with the regulations that they were charged with enforcing, the JPOs taught their families, and neighbors, what they learned from the Department of Health.

There was a warm relationship between the regular and junior officers. The JPF attended many funerals for their adult counterparts. The Evening World on June 1, 1916, reported that a 31 year-old PDNY Patrolman (Ptl.), who worked closely with the JPF to “keep the pushcart markets in lower First Avenue in proper sanitary condition” had died. Ptl. Harry H. Schwarz, Fifteenth Precinct, Fifth Street Station, was killed while “seeking to overpower three armed men in a First Avenue cellar.” The JPF marched behind the funeral procession, which left Schwartz’s residence at 722 Columbus Avenue and ended at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Queens. Several other articles bear out the fact that the JPF participated in such events, which must have left quite an impression on the boys.

According to a July 1, 1917 article reported in the New York Herald, PC Woods, accompanied by his wife, and Police Chaplain Blum, reviewed approximately 1,900 JPOs as they marched down Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. PC Woods remarked that the JPF “evidenced a great improvement in the military deportment and physical fitness of the lads since the beginning of their training. The Junior Policemen are not only ornamental. It is their duty to help the police.”

(Photo: New York Herald, July 1, 1917)

Duties Fraught With Danger:

The JPOs not only participated in parades, drills, athletic competitions, fundraising, promoting healthy habits, educating children and adults about safety and the laws, but also participated in nabbing “penny-candy pinchers,” and notifying their adult counterparts about suspected criminal activity. Evidence of events which were not without incident were found in the newspapers of the era.

On September 8, 1915, a fourteen year old JPF Patrolman was slapped and stabbed by a boy he had scolded for “chalking the sidewalk.” JPF Ptl. Edward Rosenfeld, of 1551 Southern Blvd., was treated at Fordham Hospital and released.

In another incident, eleven year old JPF Lt. Morris Schwartz of Brownsville, Brooklyn, accused 37-seven year old Daniel Gittos of assaulting him while he was attempting to break up a fight between two other boys. According to the Daily Standard Union article, on November 2, 1916, Lt. Schwartz “clung to him until a big policeman came.”

Diminutive in Stature – Heroes by Their Deaths:

Some of the duties performed by the JPOs had deadly consequences. In fact, there were three fatal incidents that remain untold, and perhaps more that were not recorded, or reported in the newspapers. The three incidents found describe actions by the JPOs that led to what can only be described then, and now, as “line of duty deaths.”

Had the deaths been of adult police officers, the men would undoubtedly have been recognized as “heroes.” The mens’ deaths would have been characterized as “line of duty deaths.” Their names would have been forever remembered by the PDNY and inscribed on the “Roll of Honor.” However, since the “officers” were children, their heroic actions have largely been forgotten and lost to time.

Sadly, according to the office of the First Deputy Commissioner of the PDNY, “no official records” of the incidents exist in the PDNY’s records. The selfless bravery, by the JPOs, in the performance of their official duties, has, been largely forgotten.

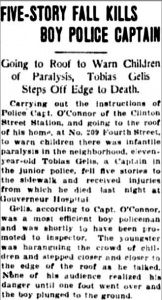

On July 11, 1916, the Evening World reported, the death of eleven year old JPO Tobias Gelis. JPO Gelis was acting on the order of a PDNY Captain. His orders were to warn neighborhood children about recent cases of infantile paralysis. As was the case with the JPOs acting as liaisons, and translators for their relatives, and others, the message would likely be carried to adults.

The young JPO was on the rooftop of his home, a five story tenement. As he spoke to the group, which was described as “haranguing” him, he stepped off of the roof and fell to his death.

(Article Insert: Evening World/Photo Insert: 2014 Zillow.com)

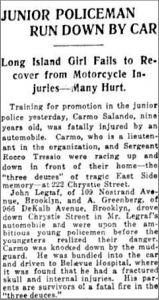

As reported by the New York Tribune on June 21, 1915, while training for promotion in the JPF by running sprints in the street in front of his home. JPF Lt. Carmo Salando, age nine, was struck and killed by an automobile.

(Insert: New York Tribune article)

JPF Sgt. Rocco Tressio, who was training with Salando, witnessed the accident, which occurred in front of their home, an apartment building located at 222 Chrystie Street.

The tenement was known in the day as the “Three Deuces. The overcrowded building, occupied mainly by Italian immigrants, “was the location of a fire on July 28,1907 which left eighteen dead.” Entire families perished. Another source (gendisasters.com) reported nineteen dead, and thirty injured, many of them appeared likely to die. The site, quoting an unnamed primary source, described the scene as “a terrific panic, in which men, maddened with fear, trampled on women and children and pushed several from ladders and fire escapes in their own efforts to reach safety.”

(Insert: New York Tribune Article)

Carmo’s death was the epitome of tragic irony for his family. The Salando family was fortunate enough to have escaped the fire without injury, and intact, only to have the “curse of the Three Deuces” catch up with them. Newspaper articles describe horrific fires, various crimes, and murders at the “Three Deuces.” Today, the original building is long gone.”

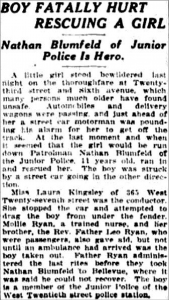

The Sun, on February 14, 1918, reported the death of JPF Ptl. Nathan Blumfeld, age eleven. Young Nathan was fatally injured when he rescued a girl from her imminent death at Sixth Ave. and 23rd St.

The girl was crossing the street which was heavily trafficked by pedestrians, automobiles, wagons, and streetcars. For an unknown reason, the girl stopped on the streetcar tracks as a streetcar rapidly approached. In what must have been a chaotic and horrifying scene to the witnesses, the motorman pounded his alarm to warn the little girl.

Witnessing the scene, JPO Blumfeld “ran in and rescued her” but tragically was struck by a streetcar going in the other direction.

The conductor, of the second streetcar, a “trained nurse” tried to render aid as did a reverend. JPO Blumfeld remained pinned under the streetcar until extricated. Despite having the fortune of immediate medical aid, and pleas to God, Nathan Blumfeld was transported by the ambulance Belleview Hospital where he lost his life while saving that of another.

(Insert: The Sun Article)

Why is it that the story of the department’s youngest officers, and their heroes remain unrecognized? In a letter to the author, First Deputy Commissioner Rafael Pineiro, who has since retired, characterized the impact of the JPF this way: “The Junior Police Force certainly holds a central role in the history and development of the PDNY’s youth-based outreach programs” including the Police Explorer program. Clearly, the circumstances in each of these three cases warrant the attention of today’s Police Commissioner. The NYPD, and their fraternal organizations, have demonstrated that they take the department’s motto “Fidelis Ad Mortem” (Faithful Unto Death) and maxim regarding those who sacrificed their lives “Never Forgotten” seriously. Now that these stories have been brought to their attention, they need to continue to do the right thing and recognize, and honor these boys.

On December 17, 1916, PC Woods wrote an editorial, in The Sun highlighting the chief accomplishments during his tenure as Commissioner. His closing statement about the JPF indicated prior to joining seventy-five percent of the boys had previous police records and that they were now less troublesome. PC Woods projected, that by spring of 1917, there would be over 6,000 JPOs “organized by companies and regiments in command of their own boy commanders under the supervision of the captains of police.”

JPF Abolished; Their Legacy Lives On:

On January 24, 1918, as a result of a NYC Mayoral election Lieutenant (Acting Captain) Richard E. Enright was appointed Acting Commissioner. Enright’s appointment was later made permanent. Enright was seen by officers as being ruthless and heavy-handed, because he took unjustified actions against those he viewed as having crossed him.

Newspaper articles reflected PC Enright’s lack of enthusiasm for the JPF. It is likely that PC Enright was aware of the findings and recommendations in a report, published in 1918, by the New York City Commissioner of Accounts on the JPF. Regarding the JPOs, the report:

“found that its membership is largely recruited from congested sections in the city, inhabited principally by foreigners of all races and creeds, who as parents, or guardians, by reason of methods of living, lack the knowledge of our local institutions and customs, limit their restriction and control over the activities of their children. Also, that following the natural tendency in boys to be inquisitive concerning matters of crime and immorality, with the aded feeling of police authority which the uniform and membership in this organization engenders, there exist evidences of danger to the morals of its members.”

The report recommended that the PC disband the JPF and direct the “future course of the organization…away from police work and into activities and associations more elevating.”

According to the PDNY’s Annual Report for the year 1918, on July 15, 1918 the auspices of the JPF were transferred from the PDNY to the NYC Board Of Education. “All shields, buttons and insignia held by its members,” as well as funds totaling $2,133.34 were transferred. Enright effectively removed the JPF from the PDNY. The legacy of this decision is that the P.S.A.L. was created under the auspices of the NYC’s Board of Education.

Enright disbanded Internal Affairs, “shook-up” the Legal Bureau, and combined other longstanding units. Incredibly, as reported by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on May 1, 1919, PC Enright “sent shivers zigzagging down police spines by announcing a good sized shakeup.” Eight Captains were “shifted” including the Fifteenth Precinct’s beloved, Capt. Sweeney, who would report to the Alexander Avenue Station in The Bronx. The article went into detail regarding only Capt. Sweeney’s transfer:

“The transfer of Capt. John F. Sweeney from the Fifth street station to the Alexander Avenue station in the Bronx caused genuine surprise. Capt. Sweeney has been at the Fifth street station for six years and he has become immensely popular with everybody. He organized the Junior Police, consisting of boys from 14 to 18 years of age, and all the young ‘cops’ swore by him. Commissioner Enright didn’t have any use for the junior force and put it out of use when he took charge of police affairs.”

Officially, on July 9, 1918, PC Enright issued General Order No. 72 which, effective at midnight on July 15, abolished the JPF. At the time, the JPF had over 6,000 members. Units existed in eighty-nine precincts, across every borough.

The order, written in the strongest and most unambiguous language, “disassociated entirely” the JPF from the PD and discontinued the name of the organization itself. PDNY commanders were ordered to retrieve all shields, buttons and insignia from the boys. After the transfer of the now nameless organization to the auspices of the Board of Education, the boys, who were once warmly welcomed by their adult counterparts, “will not be permitted in the station house.”

If, today, the JPF were a police department, it would be larger than every police department in the country, with the exception of a few: Houston (7,054), Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Chicago (13,218) and, of course, the PDNY, which has approximately 35,000 sworn officers.

After the abolition of the JPF, little written record about them, their activities, or their history was written. The Junior Policeman remains the most comprehensive publication regarding the organization, however, it came into being in 1917 and bulletins end in that year. Little was found, if written at all, about the PDNY’s JPF after it was abolished.

On September 7, 1933, an article in The Sun made reference to a baseball game played by the “New York City Junior Police Athletic League” that took place at the Polo Grounds in Upper Manhattan. The “winning team in the junior police circuit will be given a free trip to Washington D.C.” to compete against Babe Ruth’s former “home,” the St. Mary’s Industrial School of Baltimore, MD. It is believed that the name “Junior Police Athletic League” was later shortened to the Police Athletic League (P.A.L.).

(Insert: PAL Logo Fair Use)

An article in The Brooklyn Eagle, on July 27, 1951, entitled “PAL Movement Not One Person’s Idea,” draws a clear line between the JPF and P.A.L. “Police departments throughout this country have engaged in crime prevention work since the beginning of this century.” The article continued “As part of their programs they have sponsored recreation activities for their prevention and therapeutic value. In 1914, “the New York City Police Department established a junior police program which became the PAL.”

The JPF left another legacy organization. According to an article in the April 2008 edition of Police Chief Magazine, the PDNY JPF led to an idea by the Automobile Association of America (AAA). The idea was to join with the Chicago public school system’s junior police program in order to promote traffic safety at schools. Yes, the AAA “Safety Patrol” program of the 50s, 60s, and 70s descends from the PDNY’s JPF.

(Insert: www.ny.aaa.com)

When you see a member of the: P.A.L., junior police, police cadet, police explorer, AAA Safety Patrol. or similar organization, remember Capt. Sweeney, Commissioner Wood, Harry Rodman, Tobias Gelis, Carmo Salando, Nathan Blumfeld, and the scores of others who made it all possible.

Calls for Action; Recognition Awaits the JPF & Their Heroes:

“What’s the Deal With:” The PDNY’s Forgotten Kid Cops? A century after the JPF’s tenure, we have a duty to recognize and honor the important role that the JPF played in the history of New York City, and beyond. The deaths of JPOs Tobias Gellis, Carmo Salando, and Nathan Blumfeld should not continue to be unrecognized, or lost to history. The legacy of the PDNY’s JPF, which was/is carried on by the P.S.A.L., P.A.L., Junior Police, Police Explorer, and similar organizations across the country should not be dismissed or forgotten.

Temples, associations, philanthropies, museums, and related entities as well as the PDNY’s Police Commissioner, the Hon. William J. Bratton, need to recognize the Junior Police Force and its members by creating a plaque, or other appropriate recognition, of the JPF and the three known boys who died in line of duty deaths.

Please share this article so that it may reach an entity that will create or fund a memorial which will eternalize the memory of the Junior Police Force and its members.

Update! In 2020, two of the three above calls for action were met! To read the sequel to this article, click on the following link! https://NYPDHistory.com/jpf-lod/

(Insert: JPF brass uniform button from the Author’s collection)

![]()

Author’s Note: This article is an abridged version of one being finalized. As it is with writing any article relating to history, information is often received which may differ, or add to that known at the time of publication. As such, this article is story in the making and any and all comments, questions and constructive criticism is most welcome! Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.