In April 2018, a well-known and long-established badge collector contacted NYPDHistory and requested that research be conducted regarding several police shields in his collection. After dozens of hours of research and writing, NYPDHistory.com is pleased to bring you what is believed to be yet another “first ever” article; the colorful history of the policing of Coney Island.

Background

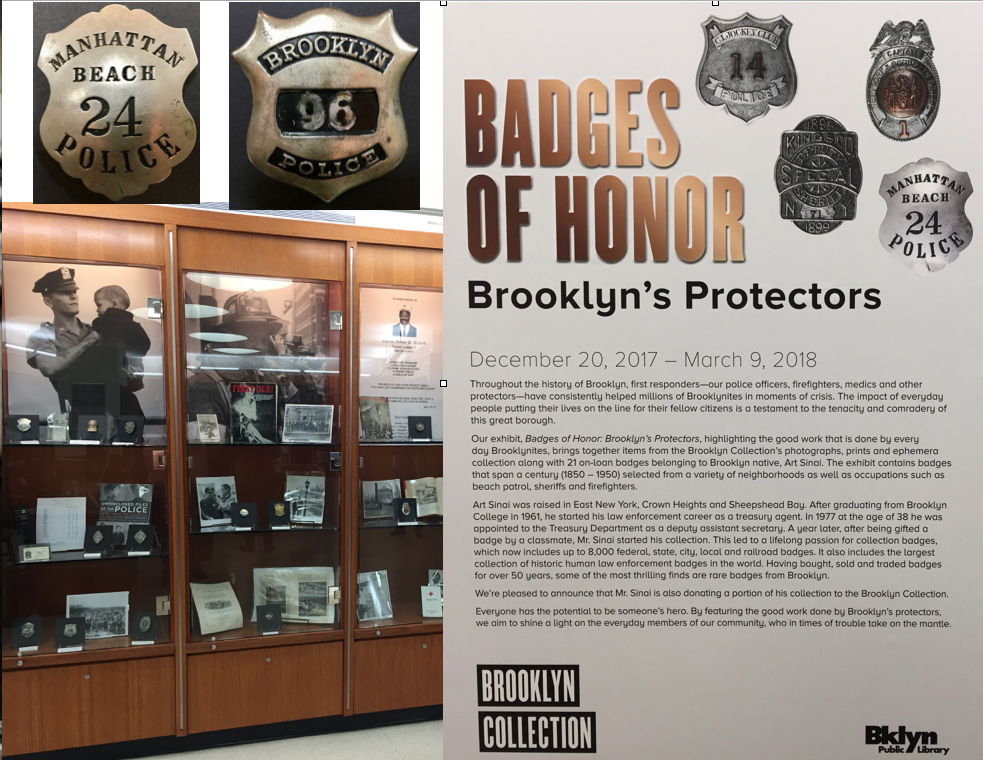

This is the story of the policing of the Town of Gravesend, Brooklyn, prior to the 1898 Consolidation that resulted in the creation of The Greater City of New York (NYC) and the Police Department of the City of New York (PDNY/NYPD). Coney Island was part of the Town of Gravesend and understanding the history of the town compliments that of Coney Island.

On January 1, 1898, the Consolidation Act gave New York City (NYC) control of the various towns, villages, cities and other municipal forces in what are today’s five boroughs. The result was the creation of the Greater City of New York – that is New York City, with it five boroughs and one municipal government, seated in Manhattan – that we know today.

In 1871, control over the policing of New York City (NYC) was returned to municipal (city) control by New York State (NYS). The state controlled Metropolitan Police District (1854-1871) was abolished and the Municipal Police Department (PD) (1871-1898) was established. The end result reduced the geographical confines of NYC’s police force from a multi-county agency to that of Manhattan Island.

The City of Brooklyn, and some towns and villages in Kings County, once again maintained their own police forces as did those in the Counties of Queens and Richmond (Staten Island). In the coming years, some towns and villages in what was lower Westchester County (today’s Borough/County of The Bronx) elected to be annexed by NYC and therefore were policed by the Municipal PD.

Introduction

As Manhattan Island (NYC) became more congested, citizens sought a place of refuge during the hot summer months where the climate was more tolerable, the bathing refreshing, and the “scene” more pleasant. Some residents fled to the Catskill Mountain region of New York while others went to the sea shores of New Jersey and New York.

Wealthy men who built their fortunes in the stock market and in the industrial era’s economy (railroads, coal, iron, construction) purchased land for investment purposes. The development of land in Brooklyn along the Long Island Sound brought the construction of enormous hotels and crowds of people. The need for seasonal surges in policing resulted in the hiring of “Special” officers and for semi-private police forces.

Hotel owners and owners of large attractions, maintained their own “police forces.” As is the case with seasonal resorts today, during the “off” season, few officers were required to maintain peace, law and order. In the “high” season (late spring, summer, early fall), of the 1870s when crowds reached 15,000 a larger number of officers were required and therefore hired. By the late 1880s, there would have been very large crowds, estimated at 80-85,000 for Pain’s fireworks and, by the mid-1890s, on weekends.

Resort owners, who were wealthy, influential and powerful, saw the need for such officers. Visitors wanted a safe environment and profits were tied to attendance. Resort owners often entered into agreements with municipalities to hire their own officers. In most cases, the men hired were retired police officers from the NYC and Brooklyn departments.

The rapid development of Coney Island resulted in it becoming a destination for day visitors, and, for those who could afford it, extended stays at what were described as some of the finest resorts in the world. Along with the large resorts, came race tracks, amusement parks, an aquarium, bathing (swimming), saloons, and small hamlets where the workers took up residence.

But what sort of police forces and what kind of men, were behind the island’s reputation for maintaining a low crime rate, while at the same time allowing for the island to have a reputation as being “wide open” for illegal sports betting, games of chance, excise violations, all under the watchful eye and protection of the very same officers?

What follows is a brief examination of the pre-Consolidation (1898) police forces of Coney Island in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. In the period, Coney Island was described by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper as “the greatest seaside resort in the world, its comparative freedom from crime of all sorts is a source of both gratification and surprise.”

Gravesend’s Coney Island Resorts; Politics + Policing = Power & Profit

In 1871, Coney Island was located in the Town of Gravesend which, until approximately 1881 was policed by the City of Brooklyn Police Department. As was the case in neighboring NYC, politics on Coney Island was a bloodsport and corruption and graft widespread. Investments in transportation by rail, carriage (omnibus), trolley and by watercraft made for a California “gold rush-like” environment along with a suitable cast of characters. Not unlike central characters in some of the spaghetti western movies of yesteryear, one individual in the frontier Town of Gravesend’s Coney Island held title to nearly every key office in the Town of Gravesend.

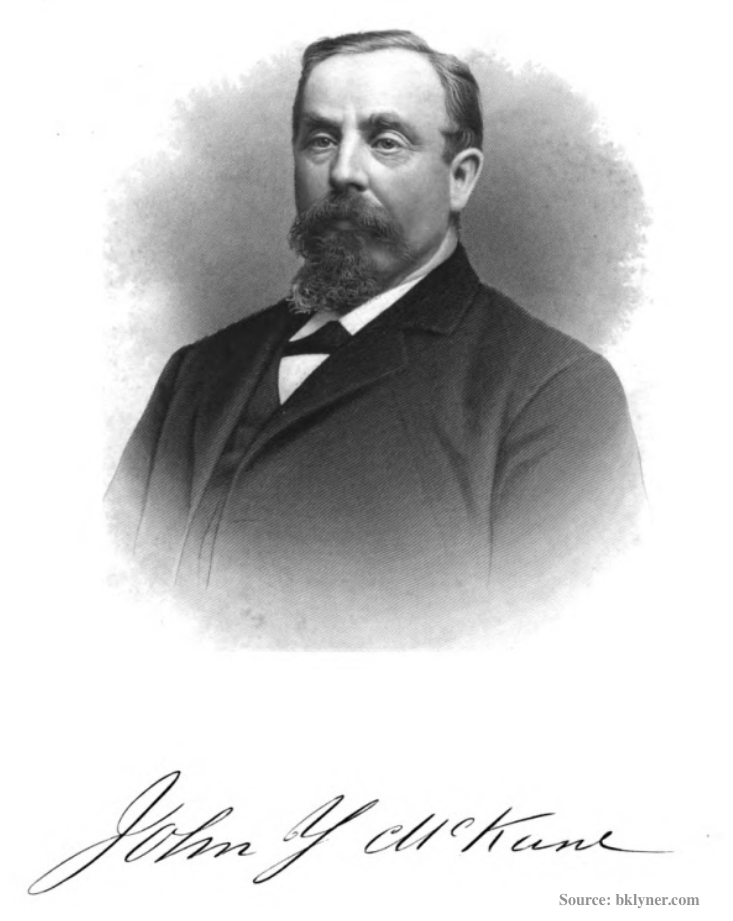

Mr. John Y. McKane, a Scottish-born immigrant, migrated to the United States as a young child. McKane recognized the opportunities in the future of Gravesend. After his 1869 election as Town Supervisor, McKane took control over the municipality and garnered a reputation as someone who (1879-1894) was both respected and feared. In 1879, citing the absence of any real police presence, McKane pushed legislation through the NYS Legislature to create one. The “New Utrecht and Gravesend Police Bill,” was sponsored by Assemblyman Douglass and, when passed, created the departments.

McKane’s power in the town and on the island was absolute. The first order of business after his having formed the Gravesend Police, was for McKane to have himself appointed both Commissioner and Chief of Police. One newspaper described the situation thusly: “If the law of the land and the will of the chief happens to coincide well and good, but if they do not so much the worse for the law.” The citizens reportedly loved the man and the environment his empire provided for the island’s inhabitants and employees.

Simultaneously, McKane was the Town Supervisor, President of the Town Board, President of the Board of Health, President of the Water Board, Chairman of the Democratic and Republican parties, Chief of the Town of Gravesend Police Department, Chairman of Excise Commissioners, Chairman of the Highway Commissioners, Chairman of the License Commissioners, Chairman of the Commissioners of Public Lands, and Chairman of Sunday Schools, among other titles!

McKane’s police force was funded, in part, by fees he collected for issuing licenses to the various concessions, amusements, dance halls, saloons, shooting galleries, museums, etc. Generally ranging from $50 to $250, applicants knew that if they paid in excess of the amount of the fee, the Chief was appreciative of the applicants not asking for change.

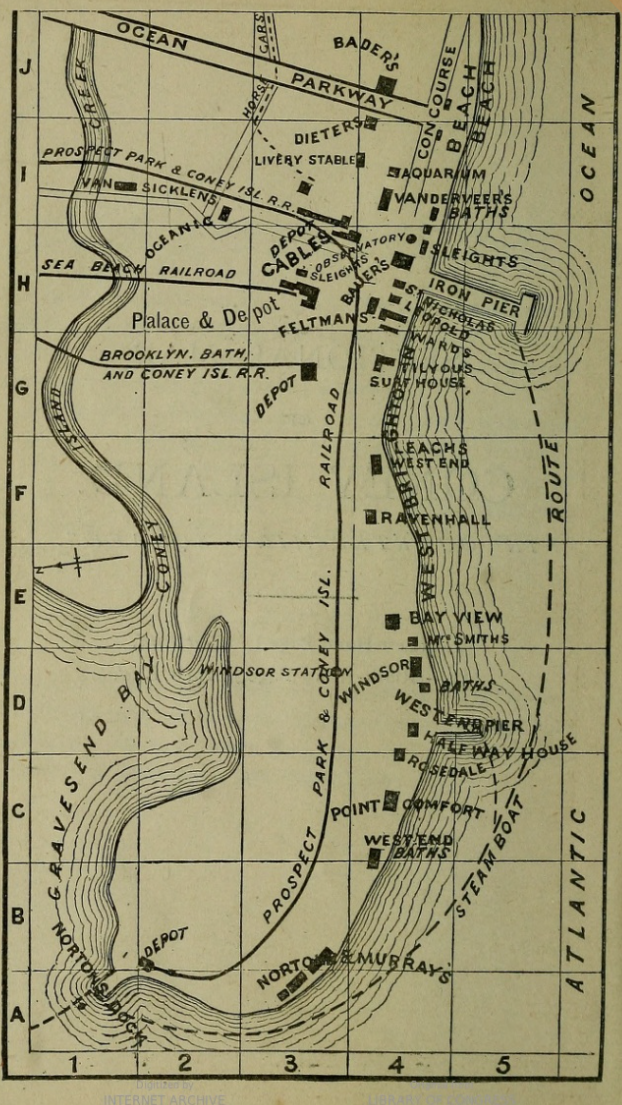

Police headquarters for the island (Coney Island) was located in the Aquarium Building, which was located in a two-story frame structure east of Vandeveer’s Hotel and the Plaza at West Brighton.

According to an 1880 source, the police officers employed by the various forces “are all sworn in as officers by the authorities of Gravesend. Well-known and capable hotel detectives are also employed by the larger hotels.” A history of the Town of Gravesend noted that McKane had “under his control 150 police, 20 of whom are regular town police, the balance being special, during the (Coney Island) season.” The document described Chief McKane as being capable of “bringing the strong hand of the law to bear upon every form of iniquity which is properly brought to his notice.”

According to a newspaper article, published in 1882, “The Gravesend police was a peculiar body, and their conduct on many occasions has subjected them to severe criticism.”

Absolute Power Brought a Town Fraught with Corruption

In 1887, Britain’s Lord Acton wrote “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Perhaps his conclusion was based in part on the decades of corruption that resulted in the NYC Democrat machine that was Tammany Hall and their corrupt Grand Sachems, such as William “Boss” Tweed. As absolute and corrupt was Tweed’s control over NYC and the PDNY, was McKane’s over Gravesend and the police departments in the town.

As was the custom of the period, with in NYC and its environs, political giants such as McKane were feted by those who benefited from the spoils, or feared the tyrant. McKane was no different from any of the other corrupt tyrants in the metropolitan area.

In September 1883, Chief McKane and eight police officers of the Town of Gravesend were indicted for “aiding and abetting gamblers.” Additionally, it was found that “Justices of the Peace are by law Police Commissioners, that they appointed the policemen at Gravesend, permitted them to be employed by the gamblers, and detailed them to witness the daily violations of law, the gamblers and those interested in the races paying their salaries.”

In a notable case, Chief McKane and his band of “loyal” officers raided a room at the Iroquois Club, the occupants of which had made a hasty escape leaving behind evidence of their crime. Based on the allegations, evidence, the statements of witnesses and defendants, two men hired a telegraph operator who tapped into the telegraph lines between a horse race track and a sports betting pool parlor.

By receiving and delaying the information from the race track, the operator could tell the two men what the outcome of the races while he withheld the transmission to the betting parlor until one or both of his confederates could place the winning bet. $15,000 was the estimated “loss” to the betting parlor ($361,000 in 2018 dollars). Moreover, McKane lost his cut of the action.

McKane exercised all of the power afforded to him, and more, and leveraged his positions and power to make himself rich. The wealth caught the attention of NYC’s Tammany Hall and its Grand Sachem William “Boss” Tweed. It also caught the attention of a Charles A. Schieren, a Brooklyn Mayoral candidate, and William J. Gaynor, a candidate judicial candidate for NYS Supreme Court) and later for NYC Mayor) who viewed McKane as a political threat. McKane and Gaynor quickly became bitter political enemies.

The outcome of a political battle with Gaynor, an increase in taxes, and a conviction on allegations of election irregularities (such as permitting non-residents and non-resident employees to sign ballots and vote, and using the names of the dead) turned public sentiment against McKane. When official poll watchers arrived on election day, they were beaten by McKane’s police officers and fled.

In the end, McKane was sentenced to six years in prison. One source wrote “It was the sands of Coney island that made Gravesend rich and John Y. McKane a convict.” Another noted “Probably no local leader ever wielded such absolute power or was more admired and beloved by his constituents than John Y. McKane. Like William M. Tweed he was a master of men.” As for Gaynor, he could not be happier, or more relieved, that the political threat that was McKane and his empire, was no longer in the way of his aspirations to become Mayor of NYC.

An investigating committee was formed to investigate the serious allegations levied against McKane and his department. The report of the 1887 Bacon Investigating Committee’s investigation of illegal gambling on Coney island” indicated that “It is well known…that the sheriff’s officers have already been assaulted by the local (Gravesend) police” and that “every official in the County of Kings is aware of the fact (that illegal gambling was taking place in the open), and especially the police of Gravesend.”

In the summer of 1887, the Town of Gravesend issued new police shields to the regular and special officers. “The regular officers are provided with a gold plated shield surmounded (sic) by an eagle and the words “Gravesend Police,” together with the number of the badge on the face of the shield. The design for the special officers’ shield is the same, but the shield is silver.

In October 1888, Gravesend Police officer Lawler was exonerated in the shooting death of Thomas Pyatt, a negro jockey, on September 18, in the New York Hotel, Coney Island. A coroner’s inquest, held at Flatbush Town Hall, was held in connection with the incident. Lawler, while off duty at the hotel, heard gunshots in a nearby room and entered the room where he encountered Pyatt holding a revolver. Witnesses testified that Lawlor asked Pyatt to surrender, but that Pyatt raised the revolver at which time Lawler shot him three times in the shoulder.

In an 1890 interview, McKane claimed that when he became Chief of Police the island was lawless; that he hired the type of officer that knew how to deal with the thieves and lawless ruffians that inhabited the island; and that he had to learn the business of policing. McKane was quoted as having said “Then I had to discipline my men, then I had to weed out the black sheep and gather about me people on whose loyalty I could implicitly rely, who would not yield to the temptations and corruptions of the place, and after that I had to attach strongly entrenched evils.”

In the summer of 1891, a testimonial dinner, attended by 1,000 loyalists was held in West Brighton at Bauer’s Casino. The highlight of the gaudy event was the presentation of a breast shield to the “Chief.” The shield was described as:

“a gold badge with a diamond star within a circle, and upon it enameled, Chief of Police, Gravesend, Long Island; a laurel wreath worked in diamonds and emeralds surmounted with an eagle with outstretched wings set in diamonds; on the back was engraved, “Presented to the Honorable John McKane by his friends at Paul Bauer’s Casino, Coney Island. Veritas Vincit.” The badge held 229 brilliants and 110 emeralds.”

Ironically, Veritas Vincit, translates to “TRUTH PREVAILS.” Indeed!

McKane’s reign would not last forever.

Misplaced Loyalties

The loyalty of McKane’s force was tested on Election Day 1894 when McKane’s officers “sought to stifle the will of the people by stuffing the ballot boxes, and complying with his orders, his men drove watchers away from the polling booths at the point of club and pistol.

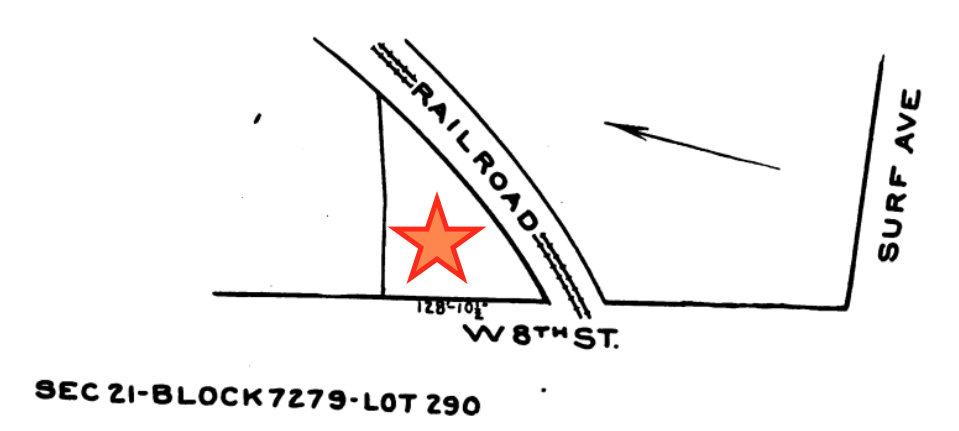

In 1893, John Y. McKane and his wife sold a piece of land, located at the intersection of West 8th Street and the railroad tracks, to the Town of Gravesend for use as a Police Precinct 169, for the amount of $6,500.

By the end of 1893, the citizens of Gravesend had their fill of McKane. High taxes, including what appeared to be an inordinate amount of money to fund the police force, outraged taxpayers. Compounding their outrage was the fact that it was disclosed that McKane had hired a blind man as a police Sergeant. The man was unable to do any “active work.” The sergeant was McKane’s son.

After McKane was sent “up the river” (the Hudson River) to Sing Sing State Prison to serve his term, things back in Gravesend, particularly at the police department, began to fall apart. Election day 1893 would be remembered as “Black Tuesday” as it was the tipping point for the McKane’s demise. One newspaper wrote “that black Tuesday…called down on Gravesend the wrath of all righteous men and which led to the downfall of the most unscrupulous gang of political cutthroats that ever existed.”

The following names of Gravesend Police officers were gleaned during research Captain John F. Hinman, Sergeant William Moynehan, Patrolmen James Whitworth, A.A. Conway, Louis Keeler, George M. Ryder, David O’Connor, Cornelius Snedeker, Joseph Bogert, John Purcell, Patrick Mooney, James Dooley, James Jimison, Johannes Kouwenhoven and officers Snediker and Ryder. Forty “special” shields “have already been issued to hotel proprietors and railroad companies for employees hired to preserve the piece.”

Gravesend PD’s Path to the 1898 Consolidation

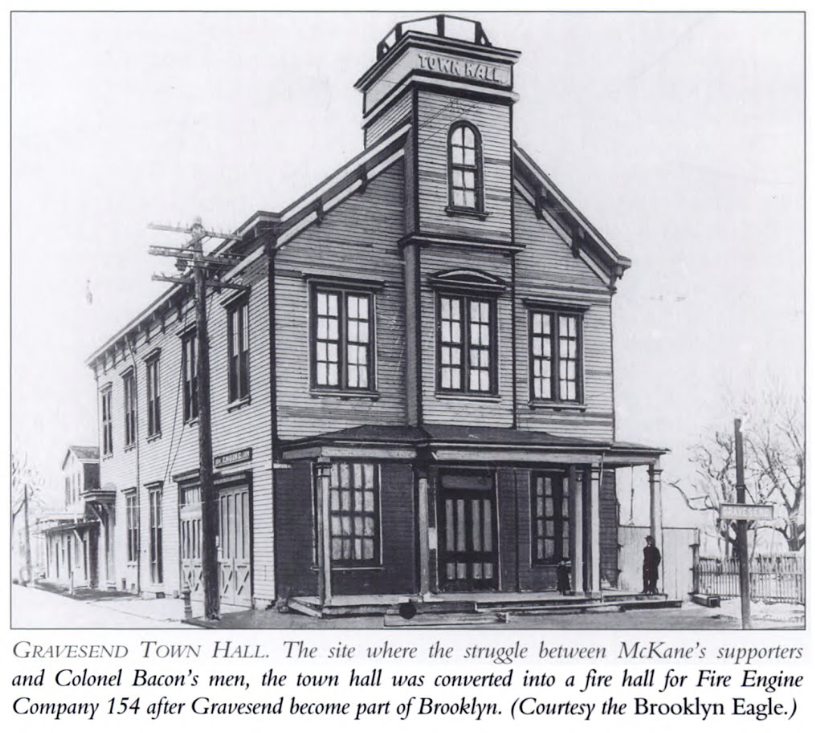

On May 6, 1894, the towns of Flatbush and Gravesend, were annexed by the City of Brooklyn, for the first time under the control of the city. Brooklyn Police In light of the actions by McKane in handling licenses and permits, Brooklyn PD Police Commissioner Leonard N. Welles made it clear that any and all licenses, including alcohol and shows, were revoked and must be issued by the Mayor of the City of Brooklyn, and that the new ward, the thirty-first, would be treated no differently than the first ward as to the Sunday, and other laws.

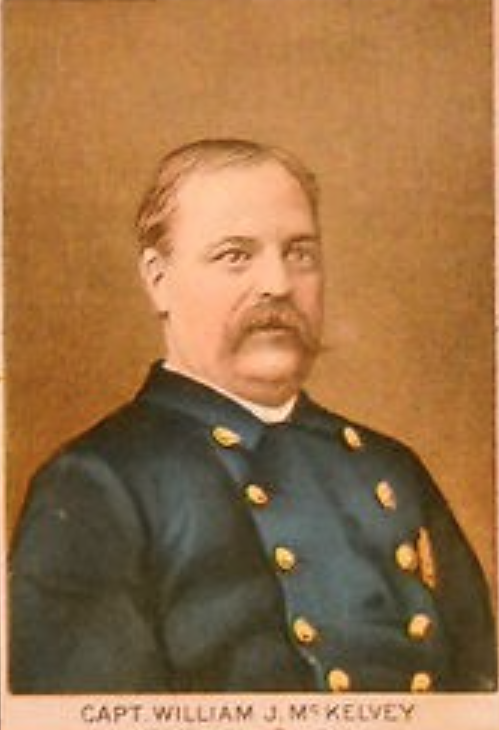

Brooklyn Police Department Inspector (Insp.) William J. McKelvey visited the old town’s police headquarters. Gravesend Chief of Police James A. Eustis, appointed April 13, 1895, was present to greet and assist McKelvey. However, Eustis could not provide any of the documents, desk blotters, muster rolls, or records requested. Furthermore there were no beds or other accommodations for the officers.

A total of forty-two handpicked Brooklyn PD officers first took control of policing Gravesend at 9:00 am on Sunday, May 5, 1894. Commissioner Welles indicated that he may order that sub-precincts be established at King’s Highway and at Sheepshead Bay, each with a Sergeant in command. The bill consolidating the Gravesend force with that of Brooklyn PD was signed by Governor Levi P. Morton (1895-1896) on May 27, 1895.

Insp. McKelvey inspected the new station-house and found that it was in an unfinished condition. Despite the setbacks, Commissioner Welles issued an oder that the new station-house be designated the City of Brooklyn’s Twenty-fourth precinct station-house. Manpower for the precinct came by way of transfers from Brooklyn’s other precincts. Sergeant Elias P. Clayton, of Brooklyn’s Eighth Precinct, was the first Commanding Officer of Brooklyn’s Coney Island Precinct.

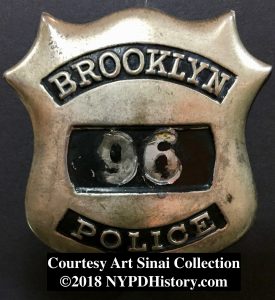

In January of 1896, officers of the Gravesend police were assimilated into the ranks of the Brooklyn PD, however Gravesend’s captains became sergeants on the Brooklyn PD and their sergeants became roundsmen. Patrolmen serving more than one year on Gravesend were transferred to Brooklyn PD without having been required to take a civil service exam.

In 1897, the City of Brooklyn erected a Magistrate’s Court, which also served as a police Precinct and fire station, at West 8th Street, north of Surf Avenue. This structure was decommissioned in 1958 and replaced with the existing NYPD 60th Precinct Station-house and fire station.

After the 1898 Consolidation, the PDNY re-designated the building as the 69th Precinct. In 1908, it was re-designated as the 169th. and in 1929, the 60th, which is the current designation of the building that was build on this lot in 1971 and remains an active NYPD Precinct!

Few, if any, of the present NYPD officers assigned to the NYPD’s 60th Precinct would guess that the land on which the present (and previous) station-houses were built was sold on March 27, 1893 for the amount of $6,500, by Mr. & Mrs. John Y. McKane.

Coney Island would continue, for decades more, to be a source of corruption for the NYPD, which subsequently took control of Coney Island on January 1, 1898 when the Consolidation Act (NYC’s five boroughs) took effect.

Coney Island would continue, for decades more, to be a source of corruption for the NYPD, which subsequently took control of Coney Island on January 1, 1898 when the Consolidation Act (NYC’s five boroughs) took effect.

Manhattan Beach Police

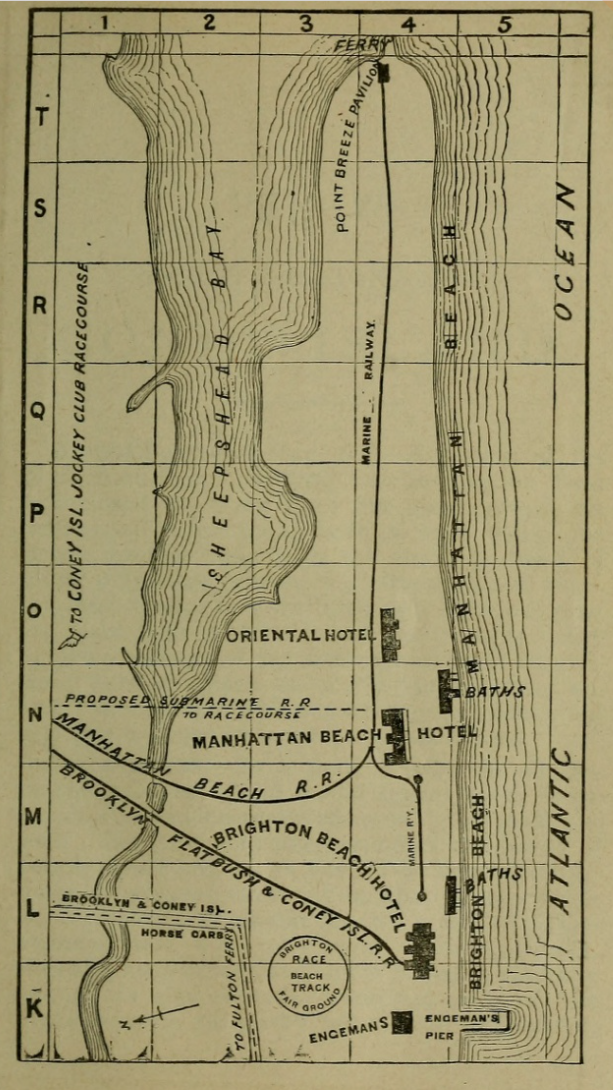

According to a Coney Island directory, published on 1880, Manhattan Beach is “the name given to all that portion of the (Coney) Island lying east of Brighton Beach, and extending to Point Breeze, the eastern extent of the Island.” Today, it is a neighborhood in Brooklyn, where Kingsborough College now sits, on the “tip” of Coney Island.

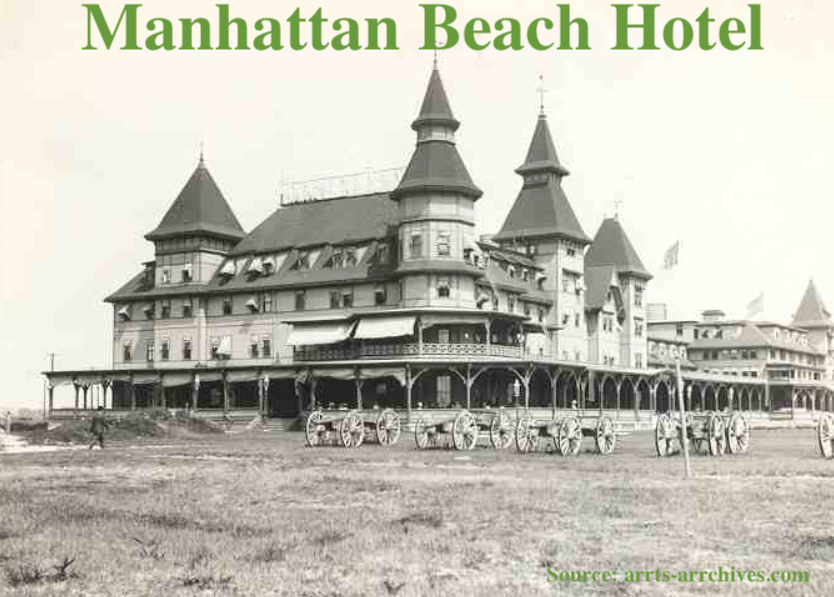

Enormous resorts were built on Manhattan Beach; the Brighton Beach Hotel 1878 (preceded by much smaller Ocean Hotel 1870), Manhattan Beach Hotel 1877, Oriental Hotel 1880, and the West Brighton Beach Hotel opened only in 1876. Throngs of visitors took overground railways (the Brooklyn, Flatbush and Coney Island Railroads) from various points (in Brooklyn) near Manhattan to get to the resorts. Ferry service was also available from various places in NYC as well as Westchester and Connecticut.

Upon arrival at the Marine Railway Station (1877), travelers were met by uniformed and plainclothes police officers who scanned the visitors in an effort to identify possible pickpockets, loafers, or thieves. In the event that they were identified, they would be sent right back on the railway.

On July 28, 1879, it was reported that in excess of 15,000 visitors used the various railways and roadways to reach the resorts. The sellout crowds were so well behaved “that the officers of the efficient Manhattan Beach police force were not obliged to make a single arrest.” The owner of the Manhattan Beach Hotel, Austin Corbin, an anti-Semite, prohibited Jews from visiting or staying at his establishments. The police enforced Corbin’s rules.

The police force enforced not only the laws, but the rules of the resorts. They were beholden to the property owners who appointed them and paid their salaries. In effect, they were employed by the owners and were involved in “settling” any disputes between their employer and others, including disputes over land ownership which sometimes resulted in fisticuffs. In one instance, in 1881, the Manhattan Beach police arrested a Town of Gravesend Police officer who attempted to stop a carpenter from removing a bridge built by Corbin across Sheepshead Bay.

On July 13, 1879, the “Manhattan Beach Police force” was described in one newspaper as having been “drilled soldier-like, and their captain has seen to it that they are, so far as their clothing is concerned, presentable. The squad numbers twenty-four, and each policeman has a certain station and a certain line of duty assigned to him. Most of the police work is done at the railroad entrance.”

By way of an example, on July 23, 1880, Capt. Curtin arrested William Wright, who he recognized from photos circulated amongst police and private detectives, as a thief from Chicago. A former convict from Illinois’ Joliet prison, Wright initially tried to conceal his identity, but the photo told a different story.

In the summer of 1882, the Manhattan Beach Hotel was policed by detectives employed by Robert A. Pinkerton, “one of the most noted and skillful detective officers in America,” whose police and detective forces were well known for their professionalism and for obtaining results. According to Pinkerton, cells used to house prisoners for arraignment were located in the “basement at the extremity of the Manhattan Beach Hotel. They are spacious, well ventilated and lighted and very secure. Adjoining the cells is a neatly furnished courtroom where prisoners are arraigned fore Judge McMahon, of Sheepshead Bay.”

Pinkerton, boasting about his men, said that there were many detectives who moved about at the Manhattan Beach and Oriental Hotels “as silently and watchfully as tigers, prepared at any moment to spring upon their prey.”

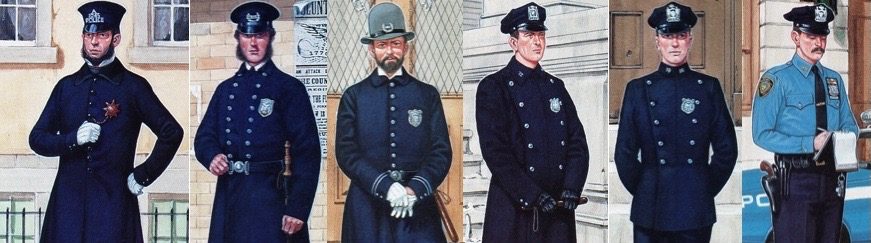

Since the opening of the hotel in 1878, the uniformed force was commanded by Captain James A. Wilkeson, described as “an intelligent and untiring officer of large experience” who was employed by Pinkerton since 1868. The uniformed force consisted of fourteen patrolmen “all strong men” who wore “the graceful white helmets of the New York force, uniforms of blue and handsome badges (presumably Pinkerton shields) of gold, silver, and blue enamel.” Capt. Wilkeson described the men as having had “long connections with the police force of the cities (New York and Brooklyn) and as being “watchful, attentive to their duties, courteous and sober.”

As is the case with resorts and municipalities that cater to tourists today, “bad” news was withheld from the newspapers.

The following names of officers of the Manhattan beach force were gleaned from the records reviewed for this brief article: Captain Curtin, Commanding Officer (1880), Captain Hotchkiss, John D. Larue (Head Detective) plus five men (1887), Detective Morehead, and Chief John Y. McKane (1892).

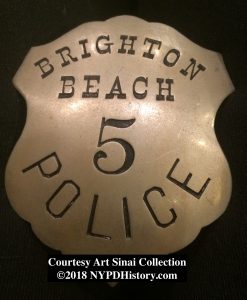

Brighton Beach Police

Brighton Beach’s development came by way of a wealthy businessman named Willian Engeman. In 1874, Engeman built the Brighton Beach Hotel, Brighton Beach Racetrack, a bathing pavilion and other attractions. The Chief of Police of the Brighton Beach force was the then retired first Chief of Police of the Brooklyn Municipal Police, (1851-1865) John S. Folk. Folk also served as the Superintendent of the Brooklyn PD from 1873-1875 and was well regarded by all.

Folk, was described in a July 23, 1878 newspaper account thusly: “Uncle John is sharp and blunt in his way – too often so – but beneath a rugged exterior there beats a kindly heart, and the many friends of him best can testify to that fact and will do so cheerfully.”

Folk took command of the force as soon as the Brighton Beach Hotel was completed and, while the number of men under his command were fewer than at Manhattan Beach, the men were “all Brooklyn men and are noted for their intelligence, affability, and familiarity with their surroundings. Captain Folk and his patrolmen are (were) employed by the Brooklyn, Flatbush, and Coney Island Railroad Company.”

The hotel also employed detectives, such as Detective James Dunphy, described as a “sharp and active officer” who was a veteran of the New York police force and was familiar with “the tricks and dodges of criminals.” Night watchmen were also employed during the off-season months.

Unlike the comparatively posh arrangements for prisoners at the Manhattan Beach Hotel “prisoners, when arrested, are taken up on the railroad to a Brooklyn (Police Department) Station house.”

The Brighton Beach race track appears to have been the source of many of the crimes committed at the resort. The complaints were largely those of theft by pickpockets and deception in connection with various betting schemes. Fistfights were not uncommon.

According to an 1882 article, as the result of a law enacted “a few years ago,” the Town of Gravesend Police Board (John Y. McKane, President) furnished twenty officers for the Summer months” to patrol the Brighton Beach section. The hotels and other resorts to the west of the eastern end’s posh hotels (near West Brighton) “have their own policemen; and in addition this portion receives – or is expected to receive – the guardianship of the Gravesend police.”

Notably, in July 1881, the Brighton Beach police directed six victims whose pocket watches were stolen to the “police inspector of New York.”

On August 30, 1882, it was reported that a “gold-headed ebony cane, together with a beautiful gold fob” (pocket watch accessory) was “presented to John S. Folk by his friends…as a token of their esteem and friendship.” At the time of the presentation, Folk was the Captain of the “Brighton Beach police squad.”

The cane was “especially made for the occasion by Mr. P.W. Taylor, 521 Fulton Street, Brooklyn” and was presented by “Office Lee and Agent Curtis” of the Brighton force.

Other Coney Island Police Forces

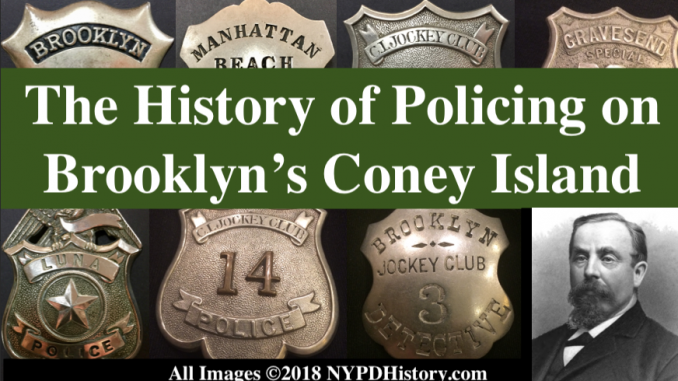

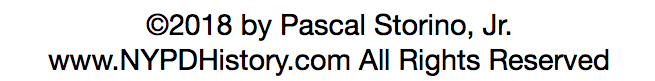

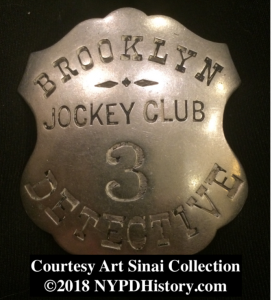

In addition to the larger forces described above, there were smaller forces that existed in Coney Island prior to the 1898 consolidation. Breast shields used by the various forces described in this article exist in the hands of private collectors and are sought after by “NYPD” collectors who know the history.

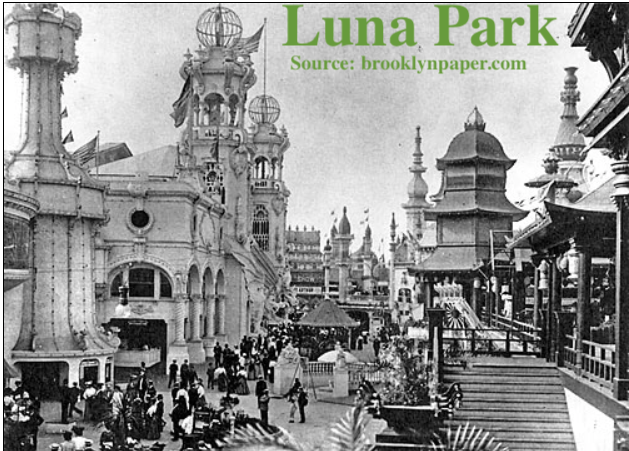

Luna Park Police

The amusement venue called Luna Park opened in 1903 at West Brighton. It appears that Luna Park too maintained their own “police” force as collectors have found shields of similar make and design to those of the resort police.

The Prospect Park and Coney Island Railroad Company

The Prospect Park and Coney Island Railroad Company employed seven police officers during the day and evening hours and three officers during the night. The men, commanded by the Prospect Park and Coney Island Railroad Company’s Superintendent Schemerhorn were experienced officers. The officers patrolled the railway and depot as well as the immediate area in the vicinity of the above.

The Iron Pier Police

The Ocean Pier and Navigation Company owned the Iron Pier and arranged for the appointment by the Board of Police Commissioners of the New York Municipal Police to employ a “strong squad of the New York Municipal police, whose tall white hats and enormous clubs have a reassuring effect upon peaceable men and a terrifying influence upon all who undertake to violate the laws.”

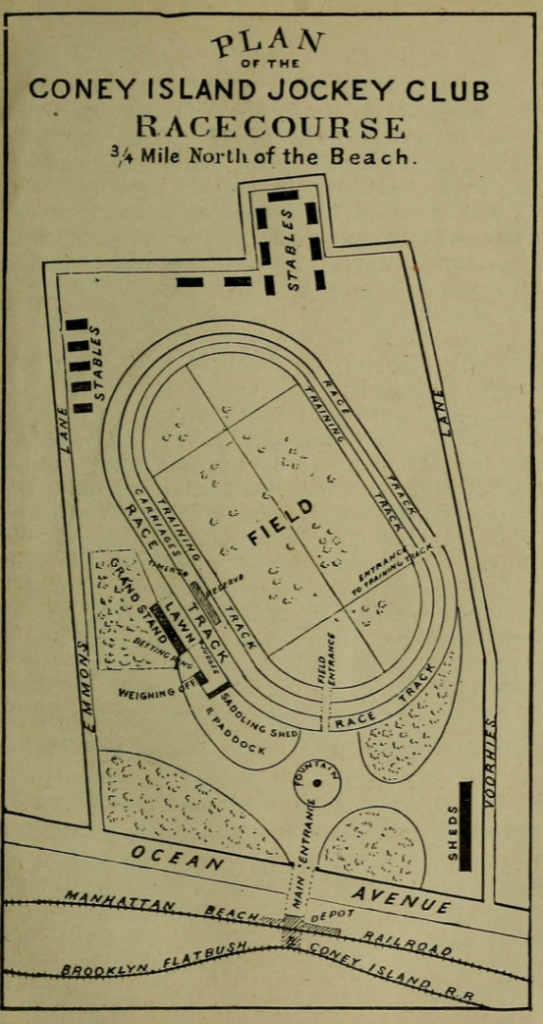

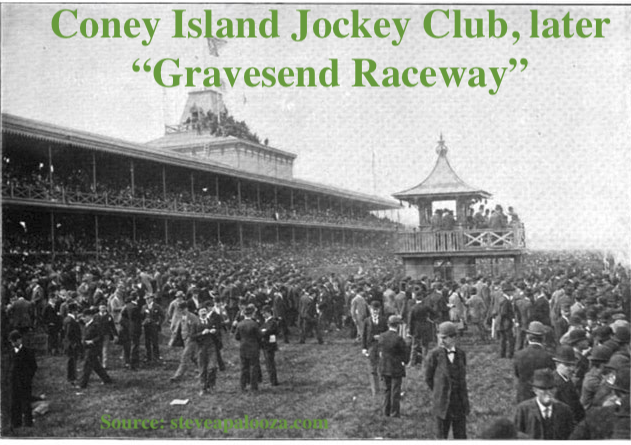

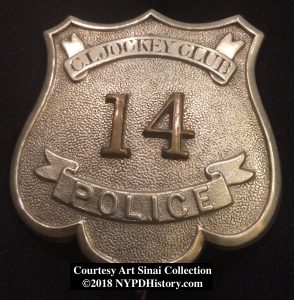

Coney Island Jockey Club

Another race course was the Coney Island Jockey Club which opened in June 1879 and the race course one year later. As was the case with the police forces of the large resorts, the Jockey Club also employed police officers to maintain order, mainly so that bettors could place their illegal bets on the races.

According to one source, in 1886, the Coney Island Jockey Club operated out of the same track. It appears that the various jockey clubs each either had space on, or lived on, the Gravesend/Sheepshead Bay track. Note: More research is needed on these forces and their relationship to the track(s).

Others

Five members of the Gravesend Police force were employed by Paul Bauer, owner of the West Brighton Beach Hotel. Similarly, members of the Gravesend force were employed to patrol the Culver Railroad line. Feltman’s Ocean Pavillion was patrolled by six men and the Sea Beach Palace by members of the Gravesend force.

Conclusion

What’s the deal with the history of the policing on Brooklyn’s Coney Island? The pre-Consolidation era was an interesting period in the history of policing. The dozens of “police forces,” and municipal police departments in the various cities, towns, and villages in today’s five boroughs of NYC each brought different individual histories to the resulting PDNY. Some entities went willingly while others fought the consolidation.

Coney Island’s post-Civil War transformation from a lightly-inhabited beach community to a world-class summer beach resort and gambling destination, was funded by several wealthy individuals under the watchful, omnipotent eye of the Town of Gravesend’s political “Boss” John Y. McKane. McKane must have been influenced by the corrupt political machine that was NYC’s Democrat Tammany Hall, and their Boss William Tweed. In the end, Tweed had little on McKane who was omnipotent in his own realm.

It was in the best financial interest of the investors and owners of the various resorts to establish and maintain a pleasant, safe and secure environment so as not to dissuade potential visitors from visiting the island. To this end, as was the case with various entities in the other boroughs, property owners sought authorization to employ regular police and “Special Officers” whose authority was afforded by their connection with other departments and the municipalities themselves.

These officers, however, were beholden and loyal to their employers more than they were to the taxpayers. This relationship fostered abuses of power and corruption which ultimately brought down McKane and his comprehensive control of Gravesend and Coney Island.

The consolidation of the various police entities into the Brooklyn PD, and later PDNY, removed control of the local politicians and resulted in a more uniform policing of Brooklyn.

If you would like more information about Coney Island in this period, visit David Sullivan’s excellent website here: http://www.heartofconeyisland.com

Note 1: Sources for all facts and inserts (photos/illustrations) are available to anyone interested.

Note 2: For a great read on the Brighton beach Hotel, click here: https://www.brownstoner.com/history/past-and-present-the-brighton-beach-hotel/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.