Introduction

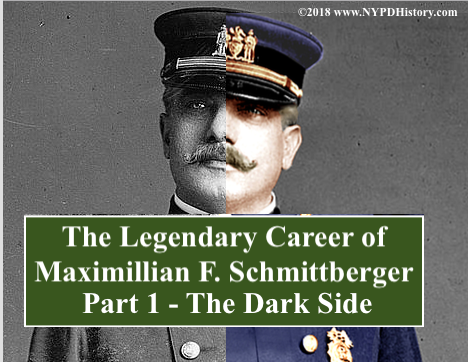

In the history of the policing of City of New York (NYC), there are few “legends” whose careers are more colorful and interesting than that of the Bavarian-born Maximilian Frances Schmittberger. Schmittberger’s 43 year career spanned the 20th century, from 1874-1917, a period of major upheaval, and change.

In his seven years as a Detective (Det.), Schmittberger claimed that he “sent over 1,200 people to the State prison whom he arrested” himself, recovered property valued at over $500,000 (over $10 million in 2017 dollars) and narrowly escaped death on several occasions. With a reputation of being fearless, he was decorated three times, two of which were awarded the department’s highest medal, the Medal of Honor.

Schmittberger rose through the ranks to Captain (Capt.) and, after having been indicted in the largest police corruption scandal of the 19th century, rose like the preverbal “Phoenix from the ashes” to lead the department. Under his command the department was largely honest and extremely professional. As Chief Inspector (equivalent of todays rank of “Chief of Department”), Schmittberger served six police commissioners.

Schmittberger’s impact on the department is evident to this day in many ways. If his career ended in 1894 with his criminal indictment, the Traffic Squad, Honor Legion, “Honor Roll Relief Fund” (later known as the “Widows & Orphans Fund”), Traffic Squad Benevolent Association, Special Police and Reserve Officers (today’s Auxiliary Police), and the Mounted Unit would likely not exist, or would not exist in today’s form.

A story of redemption, Max Schmittberger’s career serves as a reminder to New York City’s “Finest” that, regardless of the circumstances an officer may be confronted with, through perseverance, self-determination, and longevity, one can overcome all obstacles.

Background

In 1862, 11 year old Max Schmittberger, an immigrant from Bavaria (Germany), arrived in NYC. At age 22, he became a Naturalized Citizen of the United States of America (USA), and prior to his appointment as a police officer, worked as a confectioner. Schmittberger spoke four languages: English, German, Spanish, French. As a child, the first time he saw a NYC Patrolman, he told his parents that he too some day would be a police officer.

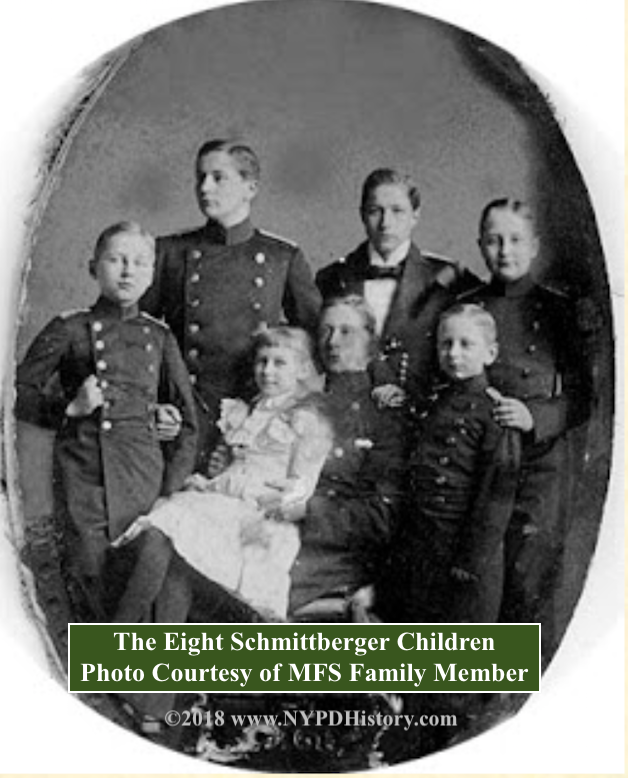

In 1880, at age 29, Schmittberger married German born Sarah Golden.

Within a few years, the Schmittbergers had two of their eight children and resided in Manhattan.

From the time of his appointment to the force to the time of his death, Schmittberger’s appearance and deportment were cause for him to stand out in a crowd. In April 1902, 50 year old Schmittberger, described himself as being six feet tall, with blue-gray eyes, a straight, medium sized nose, full head of red-greying hair, small mouth, round chin with a round face and ruddy complexion. Throughout his career Schmittberger’s tall height, chiseled facial features, light eyes, and military appearance, were noted by civilians, reporters, and officers alike.

Understanding the totality of the circumstances he faced is relatable to the circumstances many officers throughout the history of the department have faced. How Schmittberger dealt with and overcame the adversity, is a study in heroism, hypocrisy, redemption, perseverance, grit, determination, leadership, and ultimately respect. Schmittberger was a “survivor.”

Police Career

On January 8, 1874, at age 23, four months after becoming a citizen, Schmittberger was appointed as a Patrolman (Ptl.) to the Police Department of the City of New York, (PDNY). In 1876, Ptl. Schmittberger was first assigned to the 19th Precinct (Pct.), located at 220 East 59th Street. [Note: A map of precinct boundaries & station-house locations for this era appears at the bottom of this column.]

Above header of an Appointment Certificate of the Municipal Police Department from the era of Schmittberger’s appointment

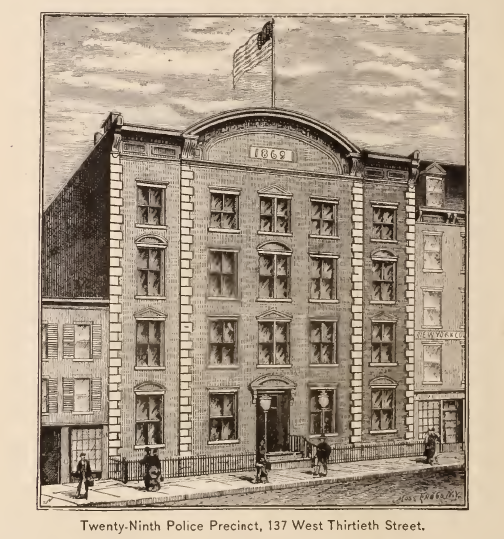

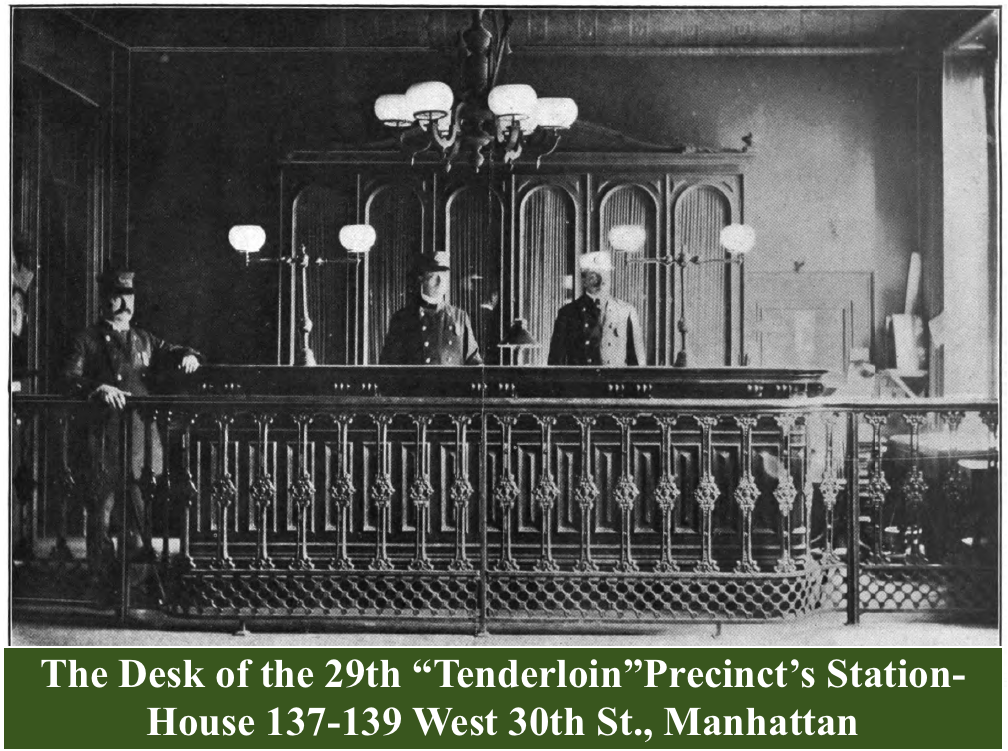

Ptl. Schmittberger was soon transferred to the 29th Pct., which was commanded by Captain (Capt.) Henry V. Steers. The 29th Pct. Station-house, was located at 137-139 West 30th St., was bounded by the confines of 14th St., 42nd St., from Fourth (today’s Park Avenue) Avenue to Seventh Ave., and included Union Square.

As often happens in police work, one of his first arrests established his reputation for the rest of his career. Schmittberger had a reputation “for fearlessness, which he retained to his last breath.” His youthful appearance and fresh uniform got the attention of a pugilist (fighter/boxer) and known cop fighter named Mike Coburn “who, when drinking, always looked for a ‘cop to lick.’ Coburn had driven a horse into a restaurant…and demanded that a bale of hay be served to the animal. Tables were overturned and the place was in an uproar when Schmittberger, then called ‘the boy cop,’…arrived and gave Coburn the worst beating he ever suffered, locked him up, and the next day sent him to prison.”

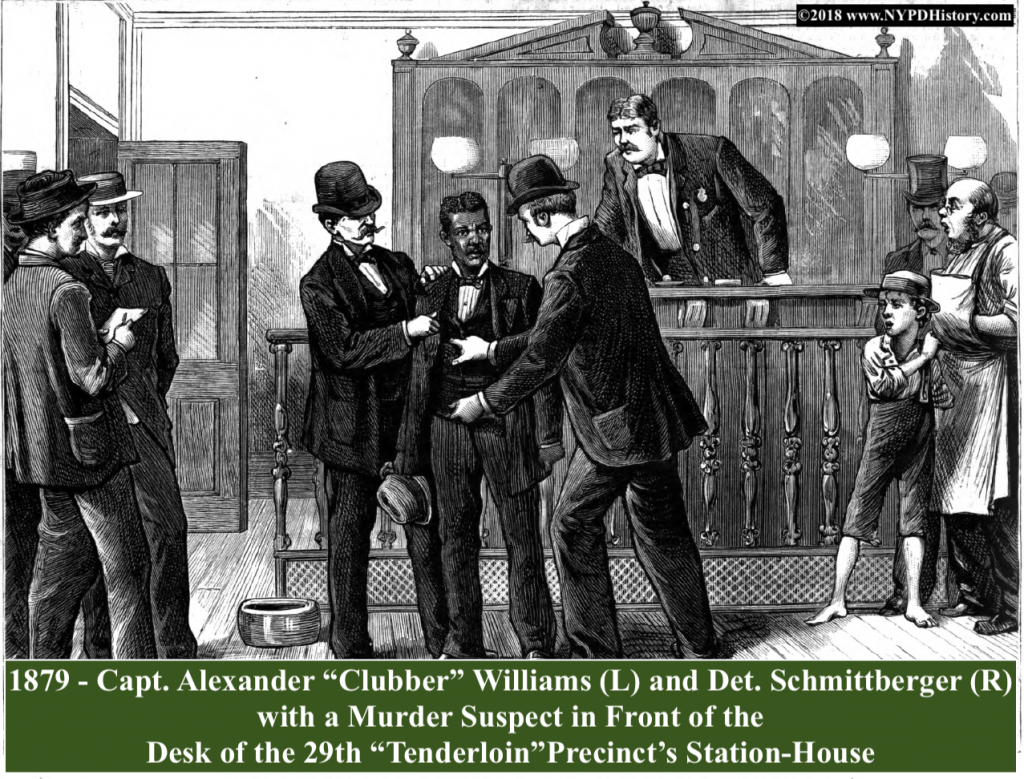

By the summer of 1877, Schmittberger was a Detective, a position known at the time as a precinct captain’s “Ward Detective” or “Wardman.” Some precincts had more than one Wardman. In the case of the 29th Pct. at the time that Schmittberger was detailed as such, there was another Ward Detective named Dunlap, who had been appointed by Capt. Steers and tended to the “disorderly houses,” bars, gambling halls, etc. located within the confines of the precinct.

Above – Capt. William & Det. Schmittberger arrest a murder – 29th Precinct – Tenderloin

In 1880, Schmittberger was promoted to the rank of Roundsman (equivalent to today’s rank of Sergeant). However he did not perform the supervisory duties of a Roundsman but, rather, remained a Detective with the rank of Roundsman.

In 1882, Roundsman Schmittberger received a “prized” medal from the “French Societies” for his “efficient discharge of duty in the arrest and conviction of Michael McGloin for the murder of Louis Hanier,” a barkeeper. McGloin was subsequently hanged.

In 1883, Roundsman Schmittberger was promoted to Sergeant (Sgt.) (equivalent to today’s rank of Lieutenant) and remained in the 29th Pct. where, during his eighteen years assigned there, he worked for a veritable “Who’s Who” of the PDNY’s Captains of the era.

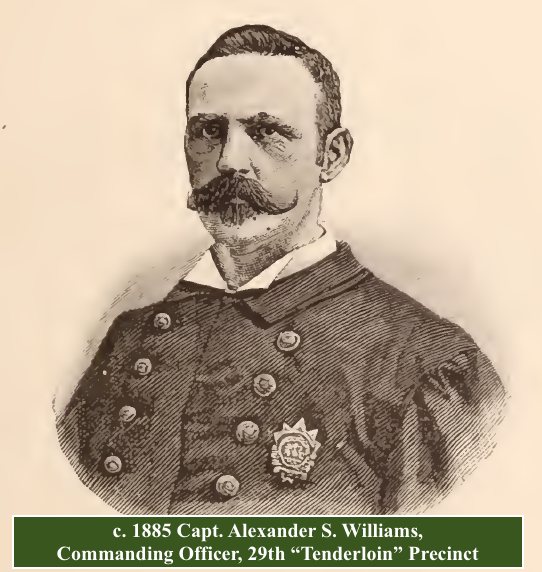

Capt. Steers was subsequently replaced by Capt. Alexander S. “Clubber” Williams, who took on the sobriquet “Clubber” from his liberal, effective use of his locust wood nightstick after he single-handedly cleared out a gang of ruffians in a bar. While many may be familiar with the saying that “There is more law in the end of a policeman’s nightstick than in a decision of the Supreme Court,” many may not know that it was Williams who coined the phrase.

It has been long held that when Capt. Williams learned of his transfer to more lucrative, graft-ridden 29th Precinct, he stated “I have had chuck for a long time, and now I’m going to eat tenderloin.” Williams later testified that he had actually said “I have been living on rump steak in the Fourth precinct, I will have some tenderloin now.” Capt. Williams testified that it was a reporter in a NYC newspaper named The Sun who, after hearing the captain’s statement coined the name “tenderloin” for the 29th Precinct.

Regardless of changes in numerical designation, has been known as the “Tenderloin Precinct” and Williams has been referred to as the “Czar of the Tenderloin.”

Capt. William’s comparison between rump and tenderloin steak had nothing to do with the cuts of beef he was able to afford, but rather the opportunity to collect far more graft in the 29th Pct. than he could in his previous command, the 4th Pct. Graft and corruption were a systemic part of the department and the city.

Capt. Williams detailed Det. Price to serve as his Ward Detective. Under Capt. Williams it was Det. Price who tended to the “disorderly houses,” bars, gambling halls, etc. in the confines of the Tenderloin Precinct. By “tended to” it was understood that it was Det. Price who collected the graft and bribes, took his 20% for doing so, and passed the remainder over to Capt. Williams.

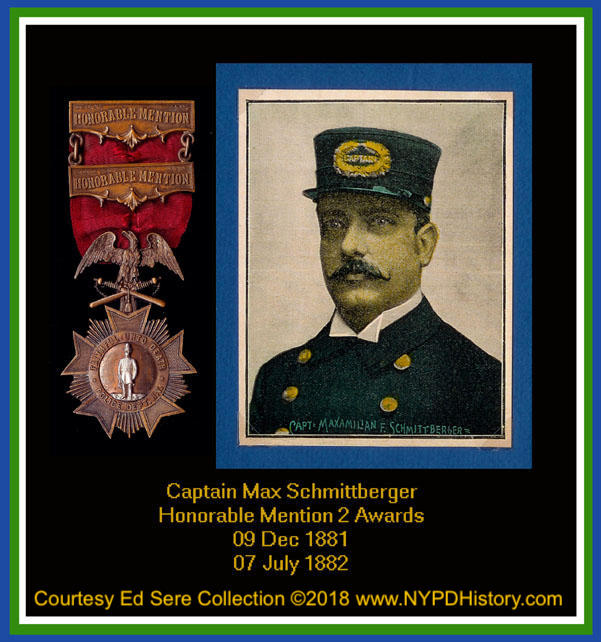

In his nine year career, Sgt. Schmittberger had been added to the Roll of Honor by the Board of Police Commissioners twice with Honorable Mention. The first Honorable Mention was awarded on December 9, 1881, for an arrest of thieves with the recovery of property. The second was awarded on July 7, 1882, for the arrest of Michael Dowdell, an “expert thief” who had shot at Schmittberger. It was the custom and practice of the department at the time to, rather than issuing a second medal, to issue a second “hanger bar,” as is depicted below.

To read the internet’s best researched, written and gorgeously illustrated article on the evolution of the department’s highest medal, the Medal of Honor, also referred to as the “Department Medal,” click here after reading this article.

In the summer of 1889, after one a-half years as the Acting Captain of the 19th Precinct, Schmittberger was assigned to the 28th Precinct, the Steamboat Squad. The Steamboat Squad was responsible for enforcing the laws relating to, and the protection of: the river fronts, docks, wharfs, ships, passengers, cargo, and swindlers of tickets and hotels.

After a tenure of thirteen months in the Steamboat Squad, in December 1890, Schmittberger was promoted to Captain Schmittberger. and commanded five Manhattan precincts before returning to command of the Tenderloin’s 29th Precinct, where, as he had done in each of his commands, Schmittberger was part and parcel to the system of corruption and graft. Throughout the above period, Schmittberger succumbed to the temptations of the graft and corruption that permeated every aspect of the city government and the department.

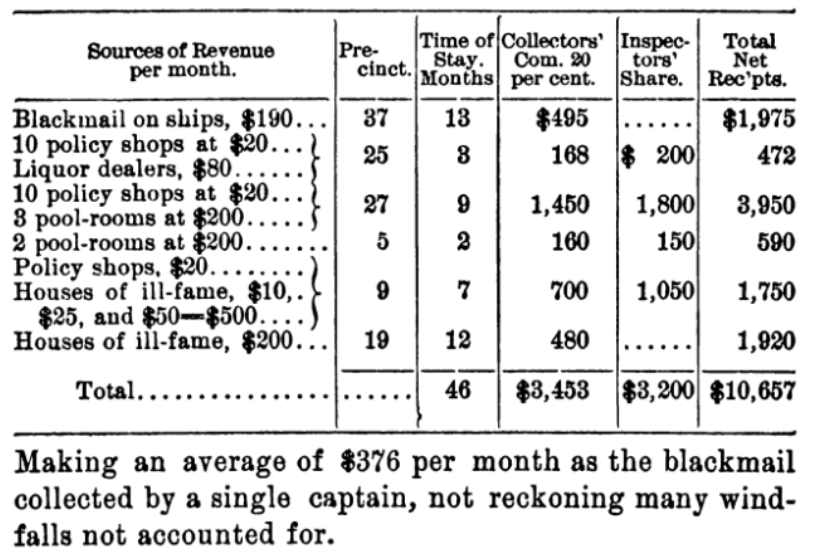

The money trail began with the saloon keepers, liquor distributors, houses of prostitution, gambling houses, and policy schemes (“the numbers” racket). Additionally, bribes were paid for appointment to and promotions within the department. Wardmen made the collections, which were set at standardized amounts by the ward leaders of Tammany Hall. The rates, however, varied from location to location based on the profitability of the entity paying them. Tammany Hall was a Democrat Party institution that literally controlled the city. The wardmen delivered the money to the precinct captain, who turned over a portion of it to the inspector, who then passed along a portion to headquarters, where the upper echelon of the department passed it along to the Tammany leaders.

Within six months, Capt. Schmittberger’s career, life, legacy, and the department itself, would change forever.

Career & Department Turned Upside Down

At Police Headquarters, located at 250 Mulberry St., Manhattan, on Saturday, October 27, 1894, Capt. Schmittberger, the Tenderloin Precinct’s 43 year old commanding officer, surrendered himself to Headquarters Det. Sgt. Reilly, who held a Bench Warrant for Schmittberger’s arrest. The warrant was issued in connection with a Grand Jury’s indictment relating to bribes allegedly received by the Capt. Schmittberger during the time he was in command of the Steamboat Squad. It was alleged that a $500 bribe was paid by Augustus Forget of the French steamer lines in return for the captain having assigned one Patrolman to their dock.

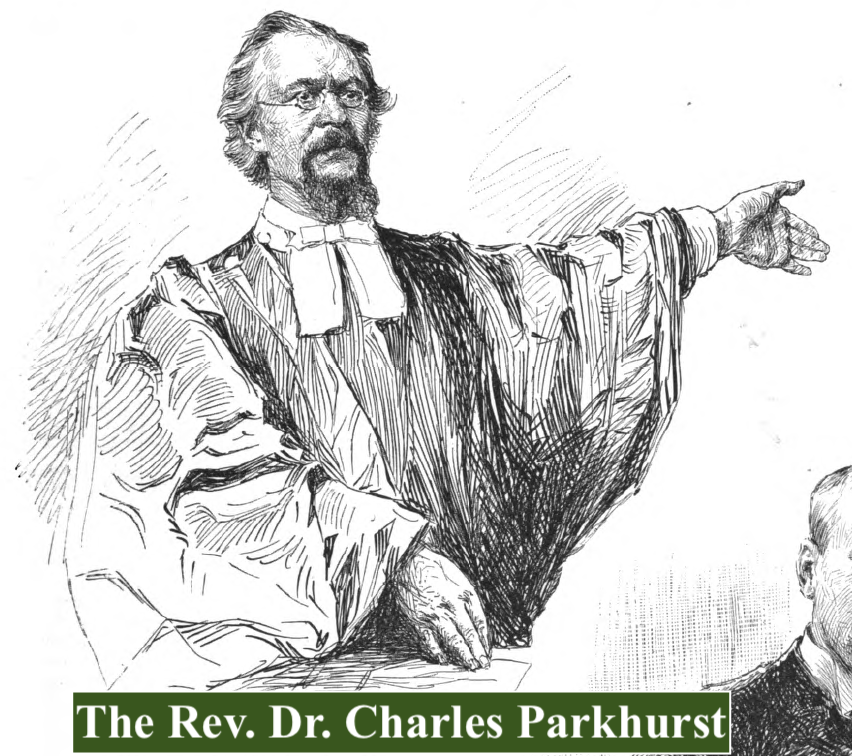

The indictment was likely not a surprise to Capt. Schmittberger. Police corruption, ranging from “protection money” to payments for appointments and promotions, had been an open “secret” for more than a decade. The resulting efforts of years of work by a small group of anti-vice and anti-corruption crusaders, led largely by the Reverend Charles Parkhurst, caught the attention of the press, some judges, and finally the Republican-controlled New York State (NYS) Legislature. The legislature seized the opportunity to attack the Tammany Hall-controlled Democratic Party and their elected and appointed officials by forming an investigative committee.

The Lexow Committee

Republican State Senator Clarence Lexow, of Nyack, was appointed Chairman of the new committee to conduct an “Investigation of the Police Department of the City of New York.” The committee’s headquarters was located, ironically, in the “Tweed Courthouse” which was (and remains) located behind City Hall. The irony is that the courthouse, was built by the corrupt Willam M. Tweed, Grand Sachem of Tammany Hall, who controlled the city with an iron fist. The cost of the courthouse’s construction, due to Tweed’s corrupt practices, was grossly inflated over the budgeted amount.

The Lexow committee met from February to December 1894. Hearings, spearheaded by the committee’s Chief Counsel John W. Goff, Esq., began on March 9, 1894. While it is Lexow’s name which is immortalized in connection with committee, (the first, serious investigation of the city’s police force) it was Goff and assistants, Frank Moss and William Travers Jerome, who served as the committee’s inquisitors.

During the committee’s 74 sessions almost 700 witnesses provided testimony that resulted in the January 8, 1895 transmittal of the committee’s 10,576 page report to the NYS Legislature. For nearly a year, newspaper boys throughout the city cried out salacious, attention-grabbing headlines as the testimony progressed, and the arrests, convictions, sentences, suspensions, and dismissals from the department that followed.

Beyond the newspapers, pro-“reform” authors, such as Lincoln Steffens, wrote in-depth articles in the weekly and monthly journals of the period such as McClure’s, Frank Leslie’s, New Republic, The Literary Digest, and others. These nationally-distributed publications brought the attention of America and beyond to the underbelly of New York’s political and police machine.

As remains the case, “word” travelled fast in the department and Capt. Schmittberger likely cringed as the committee worked to identify the presence, extent, and depth of corruption within the department. In July 1894, after they had encountered what was termed by investigators as the “Irish code of silence,” the committee sought to interview Capt. Schmittberger, in part due to his Germanic heritage. Capt. Schmittberger, however, declined the offer citing his suffering from “brain fever.”

Capt. Schmittberger’s “brain fever” may have been caused by the daily newspaper headlines, department gossip, or the convictions of officers, including a fellow Captain who was sentenced to three years in prison. After bearing his soul to his wife and a pastor, his brain fever cleared, and he saw fit to revisit the committee’s invitation. This decision changed his life and the history of the city and its police department.

Testifying “under the protection of the committee,” and with immunity from criminal prosecution, Capt. Schmittberger took the stand in the Tweed Courthouse on December 21, 1894. Explaining his rationale, Capt. Schmittberger stated “I feel that the pillars of the church are falling, and have fallen, and I feel in justice to my wife and my children that I should do this.” His testimony shed sunlight on not only his own criminality, but that of his comrades, superior officers, Tammany Hall, and the city government.

In sum and substance, Schmittberger testified that:

He did not have to pay a bribe for his appointment, or for any of his three promotions. He once acted as a middle-man for a a subordinate’s promotion to the rank of Captain by passing along a bribe to Capt. Williams.

Political influence and “pull” permeated the department. He joined Tammany Hall because influential politicians and superior police officers who were amongst its members.

As Captain of the Tenderloin’s Precinct, he was an active participant in, and benefited financially from, the system graft and corruption. It did not serve in the best interest of a patrolman to interfere with the laws prohibiting operation of a house of prostitution or gambling, or to enforce laws prohibiting the sale of alcohol on Sundays, because the illegal activities were protected by his superiors. Doing so would result in a transfer to a less-desired assignment or a far away precinct.

Captains who did not collect and pass along the graft would be “checked” into doing so by his Inspector who would embarrass the Captain by raiding the illegal operations and demonstrating to headquarters, and the public, that the Captain was not doing his job. Hence, Captains went along with the program. During his four years, in the six precincts, he netted at least $11,000.

Superintendent Thomas Byrnes was titular head of the police department, however he was prohibited from making many decisions, including promotions, without approval from a bi-partisan board of police commissioners. Capt. Schmittberger testified that he believed that Supt. Byrnes was an “honest man” and that he knew of no evidence relating to any criminal activity on the superintendent’s part.

[Note: For a more comprehensive and detailed account of Capt. Schmittberger’s testimony before the Lexow Committee, click here. A new browser window will open.]

In the end, the Lexow Committee’s Report established that there existed a systemic “organized crime and vice racket” under the protection of the PDNY, Tammany Hall, and the city’s Democratic political machine. The protection extended beyond those businesses to which Capt. Schmittberger testified (policy halls and brothels) and included: pushcart peddlers, bootblacks, sailmakers, produce merchants, steamboat operators, and other small businesses.

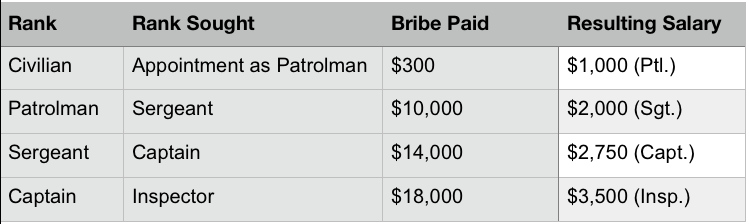

The amount of money (bribes) paid for the appointment and promotion were (approximately): Patrolman, $300; Sergeant $10,000; Captain, $14,000; and Inspector $18,000. At the same time, the salaries for these positions were $1,000 (Patrolman), $2,000 (Sergeant), $2,750 (Captain) and $3,500 (Inspector), respectively. Hence, it was understood that if paid, there was ample opportunity through graft and corruption to recoup the amount of the bribe once appointed/promoted. The total money per annum attributed to this practice was an astronomical $7,000,000.

Additional sources of “income” (graft) for an officer were rewards paid by citizens to officers for the recovery of stolen goods. This practice too had an “angle” whereby officers would collude with criminals regarding a lucrative victim or business. The thief then stole the money/item which was the officer was then fortunate enough to recover. The officer would then pay a share of the reward to the thief.

Another source of graft was the granting of permits by the precinct captain. In the era, the PDNY was responsible for issuing permits for steam boilers, parades, masquerade balls, etc. The department was also responsible for executing the city’s elections. It was disclosed that Tammany’s wishes were carried out by the police who, by various acts and methods, controlled who voted, who they voted for, and then counted the tally of votes.

The report caused enough of a public uproar that in 1893, the public elected reform-minded politicians, typically Republicans, who were opposed to the practice, including Mayor William Lafayette Strong (1895-1897). Mayor Strong appointed a bi-partisan board of four police commissioners who elected Theodore Roosevelt to serve as President of the Board of Police Commissioners (1895-1897). Roosevelt’s board instituted many reforms including civil service, a system of awards for recognition of heroic acts, a Bicycle Squad, and overall accountability through strict discipline and adherence to the command structure.

Four years later in 1897, Tammany Hall’s election slogan for the Democratic candidates, “To Hell with Reform,” reflected their disdain for the loss of income and the “reformers’” platform. The result of the election was that Tammany’s candidates were once again elected to positions which re-enabled past corrupt practices. The Tammany Tiger was back in business. The upstream river of graft money flowed once again.

The Lexow investigation, exposed the fact that the Tammany-backed Capt. William S. Devery, was the most corrupt of all Captains. Yet, after the election victory, Tammany appointed Devery to the position of Chief of Police. The appointment coincided with the creation of the Greater City of New York (five boroughs), also known as the Consolidation of 1898.

Chief Devery modified the existing system of corruption to suit his needs, and saw the addition to the city of the four outlying boroughs as an opportunity to expand the system of corruption, and fill his pockets with cash. To this end, Devery sent a corrupt police inspector to former City of Brooklyn to “teach Brooklynites how to graft.” Devery’s corrupt, abrasive, and brash reputation is likely that of the most corrupt ranking police officer to ever serve the department.

Lackluster Results of Prosecution

While the Lexow investigation resulted in the indictment of dozens of police officers, few were convicted of crimes, and, depending on sources, from one to a few served any jail or prison time. Many of the convictions were subsequently overturned on appeal.

On May 21, 1896, District Attorney John R. Fellows, asked the court to dismiss all but five of the original twenty-five indictments. Amongst the indictments dismissed were those against ex-Captain Devery, ex-Wardman Edward Glennon, Capt. Schmittberger, Ptl. Augustus G. Thorne, Capt. Jacob Siebert, and ex-Wardman Henry W. Schill.

Five cases, were transferred to the Court of General Sessions until such time as the district attorney had a chance to review them further to determine if they too should stand for trial, or be dismissed. The defendants were of wardmen and lower-ranking officers.

Five days later, Capt. Schmittberger and his wardman, Det. Michael Gannon, plead not guilty to the indictment. It was anticipated that, like the indictment of Capt. Schmittberger, this charge too would be withdrawn.

Pursuant to his cooperation agreement with Lexow, on August 7, 1896, “legal offenses, etc.,” charges and complaints against Capt. Schmittberger were dismissed by the Department.

A Continuous Fight Aimed at His Ruin

“From this time…Schmittberger’s days and nights were a continuous fight against intrigue and influence aimed at his ruin.” – The Literary Digest, November 17, 1917

In the years following his testimony, Capt. Schmittberger faced frequent transfers from one precinct to another. As remains the practice today (called “flopping”), Schmittberger’s transfers were from one area of the city, such as Staten Island, to the far reaches of the rural and undeveloped Bronx (referred to in the department as “The Goats”) and back. Let us not forget that there were no subways or extensive public transportation. Getting around was time-consuming and difficult.

In 1899 and 1900, Capt. Schmittberger was prohibited from participating in (as all Captains did) the Annual Police Parades for fear by the department that he may face derogatory comments by spectators, and perhaps officers. Capt. Schmittberger’s absence was notable and was reported in various newspapers as he was always a “favorite” of the spectators. The Morning Telegram, on June 6, 1900 commented Capt. Schmittberger “sat in solitary state at Police headquarters all day, with nobody to applaud him. He was one of the few police officials who gave testimony before the Lexow Committee, and who has been looked upon by many as a “squeeler” ever since. He is banished from police parades as a rule.” A similar article in the New York Herald opined that Capt. Schmittberger would have been commended with the Honor Men for his capture of a notorious burglar.

The following account best describes Capt. Schmittberger’s position within and outside the department after Lexow, and sets the stage for the next chapter in his life and career – a story of redemption and earned respect.

“Schmittberger set to work to establish himself among the decent citizens. He kept his job, part of the reward for his treachery, and began a task few men would have the nerve to tackle. He had destroyed his own world; his former associates, and colleagues in crime, he had transformed into bitter relentless enemies. He had no standing with honorable men; it is a question which more heartily detested him, the crooks he deserted or the clean men he served. His life was not forfeit, perhaps, because his very ignominy threw protection about him, but he was threatened. Every old association he severed at a blow; the knitting of new ties was not easy, nor was it soon accomplished.”

With nine mouths to feed at at him, Schmittberger fought to continue to collect a paycheck and to build his reputation. Part 2 of this two part article will bear out an amazing change in the department and Capt. Schmittberger who would lead the department through a period of positive change. His undeniable impact on the history of many entities, policies, procedures, and organizations within the department should be of great interest.

“That men may rise on stepping-stones of their dead selves to higher things.” – Unknown Poet’s “Truth”

[A note to the reader. These articles are the result of many hours of research and writing and all information is based on research findings. As is the case with all of our articles, citations for all information presented are available upon request. Should any reader have any comments, input, criticism, or questions, we welcome you to contact us!]

Stay tuned for Part 2 of “What’s the Deal With;” The Legendary Career of Maximillian F. Schmittberger

To receive email alerts when a new article is posted, simply enter your name & email address in the “Subscribe” box on our homepage!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.